on center panel, to the left of the Virgin’s head, M[ATE]R; on center panel, to the right of the Virgin’s head, TH[EO]N

James Jackson Jarves (1818–1888), Florence, by 1859

The center panel is carved with its two tiers of moldings from a single piece of poplar with a vertical grain, 2.7 centimeters thick at the spandrels and 1.7 centimeters thick at the lining arch. It is covered with linen and gesso on the front, sides, and back. The back may have been painted fictive porphyry, but only scattered traces of pigment remain on the burnished gesso (fig. 1). The center of the back has been worn through the layers of gesso and linen to expose the wood support, and numerous scattered losses in the gesso and in the wood have been filled with putty during the painting’s most recent restoration, in 1998. A modern bottom molding, 1.3 centimeters wide, has been added to the front of the panel. The wings are both 9 millimeters thick. Hinge scars on their reverses have been filled with putty, as have losses at the top and two bottom corners of the left wing. As described below, the paint surface has been much restored over several historical and recent campaigns; local repairs to the gilding in the center panel and left wing may date to the early nineteenth century. The faces of all the figures, with the possible exception of Saint Michael in the right wing, have been liberally reinforced; the Virgin’s blue draperies in the center panel and the dark “ground” planes in the wings are much restored, as are the white and black forms of Saint Dominic’s habit. The Virgin’s rose-colored dress and her hand and most of the figure of Saint Michael appear to be original.

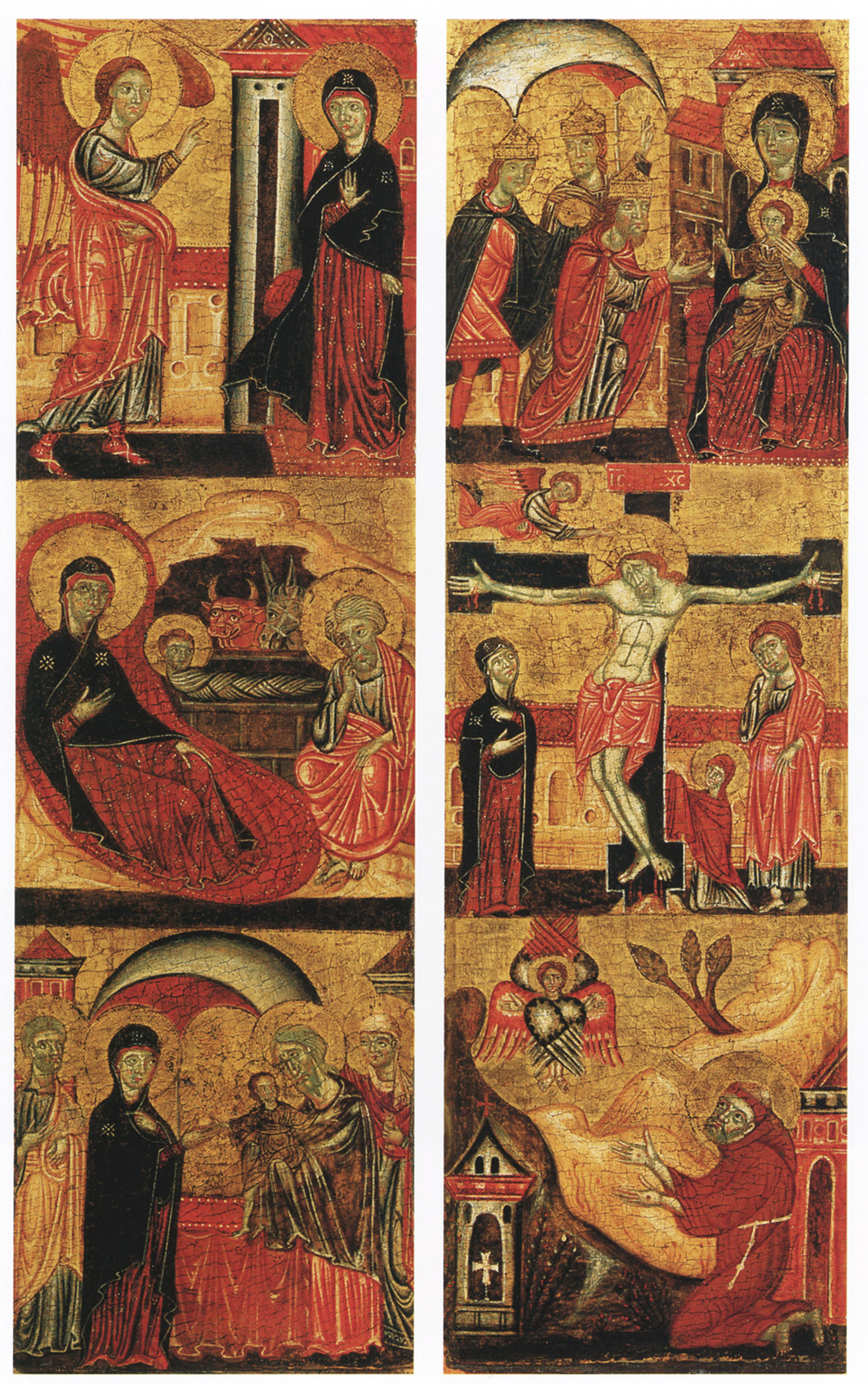

The number and frequency of bibliographic citations dedicated to this small triptych are indicative of the great rarity of two classes of object to which it belongs: Florentine paintings of the thirteenth century and completely preserved triptychs from the same period. Notwithstanding the enormous popularity of the triptych form in Italy in the fourteenth century, Kurt Weitzmann stressed that it was not a type of liturgical or devotional object native to Italy, where worshippers were unaccustomed to traveling with their objects of veneration.1 He pointed instead to the frequency with which the form is encountered in Byzantine culture beginning in the twelfth century, and he cited one particular example, in the monastery of Saint Catherine on Mount Sinai, that offers a close prototype or parallel for the structure of the Yale triptych. The triptych at Mount Sinai, attributed by Weitzmann to a French Crusader artist, shows a Crucifixion on its center panel, in an arch-topped picture field that is recessed within the panel surface.2 In the elevated spandrels of the frame are two mourning angels who would have remained visible when the wings, portraying standing figures of Moses and Aaron, were closed over the Crucifixion.

In the Yale version, the central image is similarly painted within a recessed, arch-topped pictorial field, but in this case, the representation is of the half-length Virgin and Child with a Greek inscription, “M[ATE]R TH[EO]N” (Mother of God), flanked by diminutive figures of Saints Dominic and Francis. As in the Mount Sinai painting, the spandrels above the main composition are filled with mourning angels. Instead of a full-length saint, however, the left wing is occupied by a Crucifixion, with the tiny figure of Mary Magdalen kneeling in adoration at the foot of the Cross. In the upper half of the right wing is the figure of the archangel Saint Michael with spread wings and a globe in his left hand, an image much favored in Byzantine icons; he is dressed in Byzantine imperial garb and crushes a dragon underfoot with his long spear. Standing below him are a Dominican saint with a martyr’s palm—presumably Saint Peter Martyr, who was canonized in 1253—and Saint Catherine of Alexandria. Following a Byzantine type, she is shown as a crowned princess holding a small cross in her right hand.3 Painted on the gessoed exterior of each wing are two simple crosses set against red backgrounds (fig. 2), a motif commonly found on Mount Sinai icons.4 It may be presumed that, as in the example cited above, the center panel of the triptych originally had a projecting base that would have acted as a shelf for the wings when closed and would have allowed it to stand unsupported when open. The present lower molding of the “frame” around the Virgin and Child of the Yale triptych is, in fact, modern and may well cover damaged extensions of the Virgin’s dress as well as the feet of Saints Dominic and Francis.

Early writers referring to the Yale triptych were dismissive of its quality, describing it as a “bad imitation of the Byzantine manner”5 or a “rather poor specimen . . . evidently executed by a man of very limited technical ability.”6 Richard Offner expressed greater appreciation for its rarity, calling it “a unique example in such a small scale of a well-preserved Florentine house-tabernacle of this period.”7 Although he labeled it simply as “Florentine, ca. 1270,” he followed Osvald Sirén in considering it a product of the same atelier responsible for the dossal with the Virgin and Child Enthroned between Saints Leonard and Peter and Scenes from the Life of Saint Peter in the Yale University Art Gallery, which he attributed to the Magdalen Master. George Richter rejected a direct association with the Magdalen Master or his workshop and inserted the Yale triptych into a group of works that, while echoing “certain notes” of the master’s style, were more closely related to Coppo di Marcovaldo.8 Except for Charles Seymour, Jr., who reiterated the attribution to the Magdalen Master, and Joanna Cannon, who preferred the more generic label of “Tuscan (perhaps Pisan),” most recent authors have opted for Offner’s “Florentine” label and dating.9 In an effort to narrow the stylistic field of reference, Angelo Tartuferi highlighted points of contact with the more archaic, “Pisanizing culture” of the so-called Master of Santa Maria Primerana, a personality whose identity has since been questioned by Miklós Boskovits.10

Most attempts to provide a proper assessment of the Yale triptych have failed to consider its current state of preservation and the significant alterations to its original appearance resulting from multiple campaigns of restoration. As revealed by old photographs (figs. 3–4), losses and retouches have considerably affected the appearance of several of the figures, while that of Mary Magdalen has been completely reconstructed. The heavy reinforcement of the outlines of all of the heads and draperies, moreover, has contributed to the impression of a greater coarseness of execution than is perhaps warranted by the original. Those parts of the composition that allow for clear interpretation confirm the association proposed by earlier scholars between this triptych and the Yale dossal, here attributed to a follower of Meliore christened the “Master of the Yale Dossal.”

The closest analogies for the triptych are to be found in two works on a smaller scale that have traditionally been grouped with the Yale dossal: the portable triptych with the Virgin and Child and scenes from the life of Christ in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (fig. 5), and the dismembered triptych originally comprising a much-damaged Virgin and Child in the Harvard Art Museums, Cambridge, Massachusetts (fig. 6), as well as two wings with narrative scenes in the Museo Civico Amedeo Lia, La Spezia (fig. 7).11 Both the Metropolitan Museum and Harvard/Museo Lia triptychs share technical details with the present work, such as the same punch marks and incised patterns in the haloes of all of the subsidiary figures, as well as compositional features and a similarly broad approach to the rendering of architectural elements. Included in the Lia wings, as in the Yale triptych, is the image of the penitent Magdalen at the foot of the Cross, a motif that is still rare in Tuscan painting at this date. Particularly relevant, however, is the close formal relationship between many of the figures in the Yale triptych and those in the narrative wings in New York and La Spezia, which are characterized by the same unmistakable physiognomic types, with large foreheads, tightly furrowed brows, wide-open, beady eyes, and pronounced fleshy noses. The head of the Yale Saint Michael—one of the best-preserved figures in this work—is virtually interchangeable, for example, with that of the seraph in the Stigmatization of Saint Francis, in the Lia right wing. Further analogies may be drawn between the bearded faces in three-quarter profile of the Yale Saints Dominic and Peter Martyr and the Lia Saint Francis, or between the standing Virgin in the Yale Crucifixion and the nearly identical copies of the same figure in New York and La Spezia, alike in proportions, demeanor, and dress. Such tight correspondences reflect a common vision, which, like the Yale dossal, is essentially derived from the production of Meliore in the seventh decade of the thirteenth century, when the artist was most receptive to the influence of Coppo di Marcovaldo.

Aside from the less pronounced curvature of Christ’s body in the Yale Crucifixion—more in tune with Coppo’s San Gimignano Cross than with his Pistoia Cross—the most significant difference between the Yale triptych and the above works lies in the representation of the Virgin in the center panel. The overtly byzantinizing features and elongated proportions of this figure set it apart from the rounder, more compact versions that uniformly characterize the Yale dossal and the Metropolitan and Harvard panels. It is difficult to ascertain the extent to which these distinctions denote a different hand or are simply the result of the Yale triptych’s dependence on a different iconographic formula and more conscious imitation of Byzantine sources. The image can be inserted into the group of Byzantine-derived representations of the Virgin holding the bare-legged Christ Child—an allusion to the Crucifixion—that became especially popular in Siena in the wake of Coppo’s 1261 Madonna del Bordone.12 Among the most notable examples is the half-length version of the subject in Guido da Siena’s 1270 dossal in the Pinacoteca Nazionale, Siena,13 which reflects a similar prototype and provides a useful chronological framework for the dating of the present work.

Nothing is known about the early provenance of the Yale triptych prior to it entering the collection of James Jackson Jarves. Evidence of a former ownership may once have been provided by a coat of arms—of an individual or institution—that was probably included on the gessoed back of the center panel, in the area where the painted surface has been deliberately scraped down to the level of the wood underneath. Based on the presence of Saint Dominic in the position of honor on the Virgin’s right and the inclusion of Saint Peter Martyr in the right wing, Seymour hypothesized that a Dominican friar may have commissioned the triptych for his private devotions or travels. Cannon proposed that the addition of the smaller figure of Saint Francis, squeezed in almost as an afterthought between the Virgin and the frame, indicated the triptych was executed at a “moment of solidarity” between the two mendicant orders or that its owner was a layperson under the sway of both orders.14 The presence of the Magdalen at the foot of the Cross, which underscores the penitential character of the image, may also point to an association with one of the lay communities of penitents and disciplinati that emerged in the wake of both Dominican and Franciscan preaching.15 The motif has traditionally been viewed in terms of Franciscan piety, with the figure of the Magdalen as a replacement for that of Saint Francis before the Cross. The preaching of penance, however, was just as central to the Dominican order, which by 1297 had unofficially claimed Mary Magdalen—the “paradigmatic penitential saint”—as its patroness.16 The central role played by the Dominicans, as much as the Franciscans, in mediating artistic exchanges between Italy and the Byzantine East would account for the intimate knowledge of Byzantine sources that is reflected in both the structural and compositional similarities of the Yale triptych to Crusader icons.17 —PP

Published References

Jarves, James Jackson. Descriptive Catalogue of “Old Masters” Collected by James J. Jarves to Illustrate the History of Painting from A.D. 1200 to the Best Periods of Italian Art. Cambridge, Mass.: H. O. Houghton, 1860., 42, no. 11; Sturgis, Russell, Jr. Manual of the Jarves Collection of Early Italian Pictures. New Haven: Yale College, 1868., 19, no. 3; W. F. Brown, Boston. Catalogue of the Jarves Collection of Early Italian Pictures. Sale cat. November 9, 1871., 11, no. 3; Sirén, Osvald. A Descriptive Catalogue of the Pictures in the Jarves Collection Belonging to Yale University. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1916., 15, no. 4; van Marle, Raimond. The Development of the Italian Schools of Painting. Vol. 1. The Hague: M. Nijhoff, 1923., 336n1, 355–58, fig. 192; Offner, Richard. Italian Primitives at Yale University: Comments and Revisions. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1927., 2, 13, fig. 5; Richter, George Martin. “Megliore di Jacopo and the Magdalen Master.” Burlington Magazine 57, no. 332 (November 1930): 223–36., 230n13; Sandberg-Vavalà, Evelyn. L’iconografia della Madonna col Bambino nella pittura italiana del dugento. Siena: San Bernardino, 1934., 37, no. 83; Arts of the Middle Ages: A Loan Exhibition. Exh. cat. Boston: Museum of Fine Arts, 1940., 17, no. 48; Kaftal, George. St. Dominic in Early Tuscan Painting. Oxford: Blackfriars, 1948., 22–25, no. 2, figs. II(1), II(2); Garrison, Edward B. Italian Romanesque Panel Painting: An Illustrated Index. Florence: Leo S. Olschki, 1949., 125, no. 330; Steegmuller, Francis. The Two Lives of James Jackson Jarves. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1951., 293; Kaftal, George. Iconography of the Saints in Tuscan Painting. Florence: Sansoni, 1952., col. 312, fig. b; Stubblebine, James H. Guido da Siena. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1964., 85; Seymour, Charles, Jr. Early Italian Paintings in the Yale University Art Gallery. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1970., 11–13, no. 2; Fredericksen, Burton B., and Federico Zeri. Census of Pre-Nineteenth-Century Italian Paintings in North American Public Collections. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1972., 217; Ritchie, Andrew Carnduff, and Katharine B. Neilson. Selected Paintings and Sculpture from the Yale University Art Gallery. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1972., no. 1; Cannon, Joanna. “Dominican Patronage of the Arts in Central Italy: The Provincia Romana, c. 1220–c. 1320.” Ph.D. diss., Courtauld Institute of Art, University of London, 1980., 175, 181n47, 204, 209, 256, 269, 326; Weitzmann, Kurt. “Crusader Icons and Maniera Greca.” In Byzanz und der Westen: Studien zur Kunst des europäischen Mittelalters, ed. Irmgard Hutter, 143–70. Vienna: Österreichische Akademie der Wissenschaften, 1984., 153, pl. 58, fig. 12; Tartuferi, Angelo. “Pittura fiorentina del duecento.” In La pittura in Italia: Il duecento e il trecento, ed. Enrico Castelnuovo, 1:267–82. Milan: Electa, 1986., 274, 282n28; Tartuferi, Angelo. La pittura a Firenze nel duecento. Florence: Alberto Bruschi, 1990., 38, 52n4, fig. 107; Kenney, Elise K., ed. Handbook of the Collections: Yale University Art Gallery. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1992., 131; Cook, William R. Images of Saint Francis of Assisi in Painting, Stone and Glass from the Earliest Images to ca. 1320 in Italy. Florence: Leo S. Olschki, 1999., 135–36, fig. 108; Garland, Patricia Sherwin. “Recent Solutions to Problems Presented by the Yale Collection.” In Early Italian Paintings: Approaches to Conservation; Proceedings of a Symposium at the Yale University Art Gallery, April 2002, ed. Patricia Sherwin Garland, 54–70. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 2003., 64–65, 147, pl. 5, fig. 3.10; Schmidt, Victor M. Painted Piety: Panel Paintings for Personal Devotion in Tuscany, 1250–1400. Florence: Centro Di, 2005., 32–33, fig. 14, 67n55; Cannon, Joanna. Religious Poverty, Visual Riches: Art in the Dominican Churches of Central Italy in the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2013., 208–12, 383n36, fig. 188

Notes

-

Weitzmann, Kurt. “Crusader Icons and Maniera Greca.” In Byzanz und der Westen: Studien zur Kunst des europäischen Mittelalters, ed. Irmgard Hutter, 143–70. Vienna: Österreichische Akademie der Wissenschaften, 1984., 152–53. ↩︎

-

Weitzmann, Kurt. “Crusader Icons and Maniera Greca.” In Byzanz und der Westen: Studien zur Kunst des europäischen Mittelalters, ed. Irmgard Hutter, 143–70. Vienna: Österreichische Akademie der Wissenschaften, 1984., pl. 58, no. 11. ↩︎

-

For a comparable image, see the thirteenth-century dossal Saint Catherine of Alexandria and Scenes from Her Life in the Museo Civico, Pisa (inv. no. 3), which was probably copied from a Mount Sinai icon; Weitzmann, Kurt. “Crusader Icons and Maniera Greca.” In Byzanz und der Westen: Studien zur Kunst des europäischen Mittelalters, ed. Irmgard Hutter, 143–70. Vienna: Österreichische Akademie der Wissenschaften, 1984., 154, figs. 13–14. ↩︎

-

Schmidt, Victor M. Painted Piety: Panel Paintings for Personal Devotion in Tuscany, 1250–1400. Florence: Centro Di, 2005., 45 (with previous bibliography). ↩︎

-

Sturgis, Russell, Jr. Manual of the Jarves Collection of Early Italian Pictures. New Haven: Yale College, 1868., 19, no. 3. ↩︎

-

Sirén, Osvald. A Descriptive Catalogue of the Pictures in the Jarves Collection Belonging to Yale University. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1916., 15, no. 4. ↩︎

-

Offner, Richard. Italian Primitives at Yale University: Comments and Revisions. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1927., 2. ↩︎

-

Richter, George Martin. “Megliore di Jacopo and the Magdalen Master.” Burlington Magazine 57, no. 332 (November 1930): 223–36., 230n13. ↩︎

-

Seymour, Charles, Jr. Early Italian Paintings in the Yale University Art Gallery. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1970., 11–13, no. 2; and Cannon, Joanna. Religious Poverty, Visual Riches: Art in the Dominican Churches of Central Italy in the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2013., 208. ↩︎

-

Tartuferi, Angelo. La pittura a Firenze nel duecento. Florence: Alberto Bruschi, 1990., 38; and Boskovits, Miklós, with Ada Labriola and Angelo Tartuferi. A Critical and Historical Corpus of Florentine Painting. Sec. 1, vol. 1, The Origins of Florentine Painting, 1100–1270. Trans. Robert Erich Wolf. Florence: Giunti, 1993., 105–8. Boskovits preferred to recognize in the Santa Maria Primerana grouping the late career of the more prolific Master of Crucifix 434 (named after a painted cross in the Gallerie degli Uffizi, Florence). ↩︎

-

The Lia panels, still relatively unknown to scholars, are illustrated in Zeri, Federico, and Andrea G. De Marchi. Dipinti: La Spezia, Museo Civico Amedeo Lia. Cataloghi del Museo Civico Amadeo Lia 3. Cinisello Balsamo, Milan: Silvana, 1997., 204–5, nos. 87–88, where they are catalogued with some reservation as works of the Magdalen Master. ↩︎

-

Corrie, Rebecca. “Coppo di Marcovaldo’s Madonna del Bordone and the Meaning of the Bare-Legged Christ Child in Siena and the East.” Gesta 35, no. 1 (1996): 43–65., 43–65. ↩︎

-

Inv. no. 7. ↩︎

-

Cannon, Joanna. Religious Poverty, Visual Riches: Art in the Dominican Churches of Central Italy in the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2013., 208–9. Cannon, Joanna. “Dominican Patronage of the Arts in Central Italy: The Provincia Romana, c. 1220–c. 1320.” Ph.D. diss., Courtauld Institute of Art, University of London, 1980., 209, points out that the representation of the two saints together is not unusual in the period preceding the Council of Lyon of 1274, when the two orders were united in their fight for official recognition. In the half century following the council, Francis is almost never included in Dominican paintings. ↩︎

-

Jansen, Katherine L. “Mary Magdalen and the Mendicants: The Preaching of Penance in the Late Middle Ages.” Journal of Medieval History 21 (1995): 1–25., 4–5n13. For Dominican penitential communities in thirteenth-century Florence, beginning with those closely affiliated with Santa Maria Novella, see Benvenuti Papi, Anna. “In castro poenitentiae”: Santità e società femminile nell’Italia medievale. Rome: Herder, 1990., 17–41, 593–634. Among the earliest female communities associated with the Dominicans were those of Sant’Agnese di Borgo San Lorenzo in Mugello, supposedly founded by Peter Martyr, and San Iacopo in Pian di Ripoli, comprised of matrons and widows from some of the most prominent Florentine families. The monastery in Pian di Ripoli had begun as a settlement of Dominican brothers, who handed it over to a small community of pinzochere della penitenza in 1229. The community became so successful that in 1292 the site in Pian di Ripoli had to be abandoned because of overcrowding. The nuns resettled inside Florence, split between the new monasteries of San Jacopo di Ripoli and San Domenico in Cafaggio. See del Migliore, Ferdinando Leopoldo. Firenze: Città nobilissima illustrata. Florence: Stella, 1684., 231–35; and Richa, Giuseppe. Notizie istoriche delle chiese fiorentine divise ne’suoi quartieri. Vol. 4, Del quartiere di Santa Maria Novella: Parte seconda. Florence: Pietro Gaetano Viviani, 1756., 293–311. ↩︎

-

Jansen, Katherine L. “Mary Magdalen and the Mendicants: The Preaching of Penance in the Late Middle Ages.” Journal of Medieval History 21 (1995): 1–25., 2n3. ↩︎

-

On Dominican missionary activity in the Holy Land and elsewhere, see Derbes, Anne, and Amy Neff. “Italy, the Mendicant Orders, and the Byzantine Sphere.” In Byzantium: Faith and Power (1261–1557), ed. Helen C. Evans, 449–61, 603–6. Exh. cat. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2004., 449–61 (with previous bibliography). ↩︎