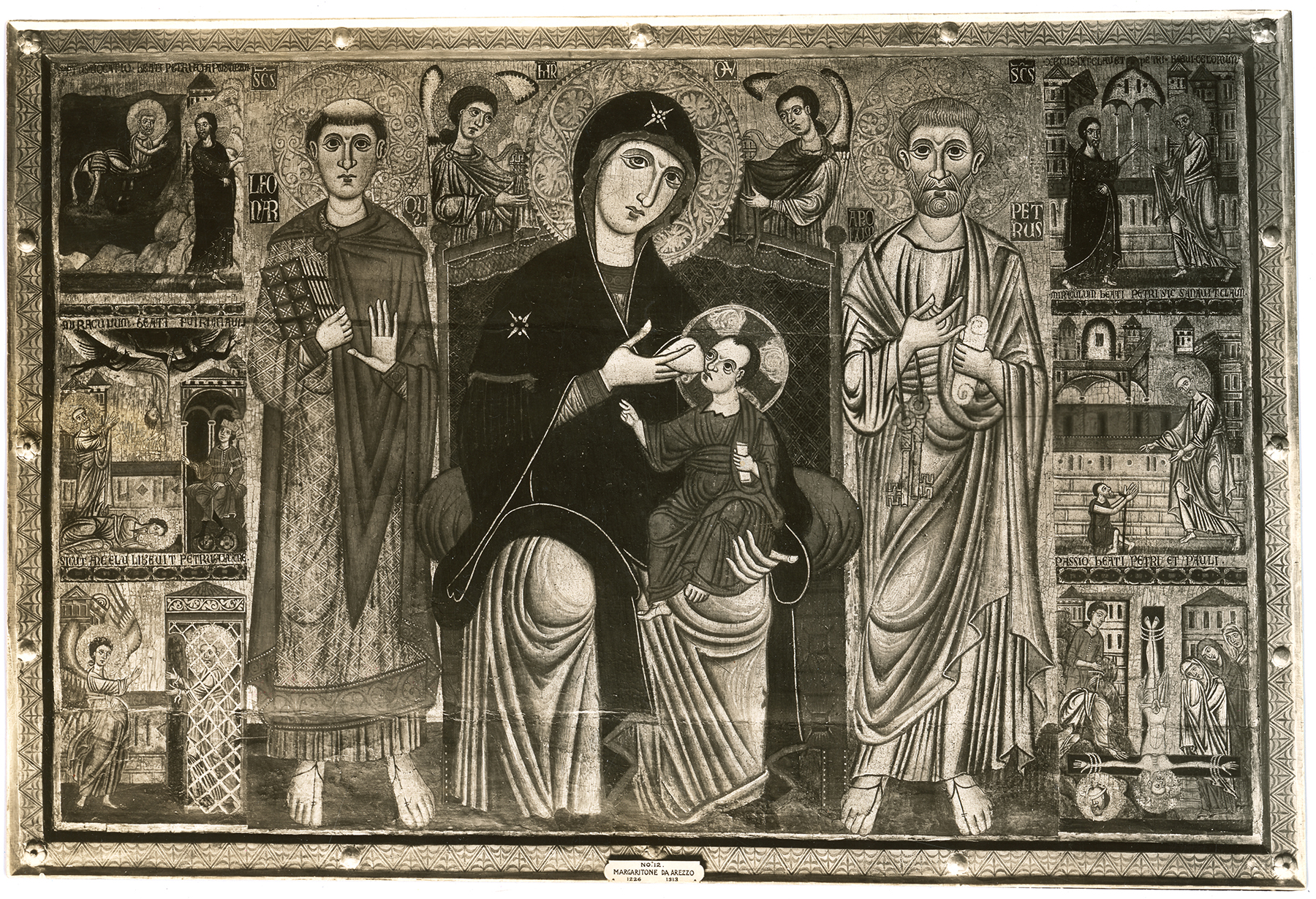

to the left of the halo of Saint Leonard, S[AN]C[TU]S LEONAR[DUS]; to the right of the halo of Saint Peter, S[AN]C[TU]S PETRUS; above the Virgin, M[ATE]R TH[EO]N; above the Calling of Saints Peter and Andrew, [ . . . ] CHRISTUS CLAMAVIT(?) PETRUM ET ANDREAM; above the Fall of Simon Magus, MIRACULUM BEATI PETRI [ . . . ] ; above Saint Peter Freed from Prison, SICUT ANGELUS LIBERAVIT PETRUM CARCERE; above Christ Giving the Keys of the Church to Saint Peter, [illegible]; above Saint Peter Healing the Paralytic, MIRACULUM BEATI PETRI SICUT SANAVIT [ . . . ]; above the Martyrdoms of Saints Peter and Paul, PASSIO BEATI PETRI ET PAULI

James Jackson Jarves (1818–1888), Florence, by 1859

The panel support is comprised of two planks of fir (abete), oriented horizontally, secured along their join (at approximately the level of the Christ Child’s knees) by three dowel pegs. The support has been thinned to a depth of 1.5 centimeters, possibly when the painting was cradled in 1929, but may have been approximately 3 centimeters in depth originally, judging by the half-exposed dowel channels. There are no indications of nails securing original battens anywhere in the panel. The engaged frame, 4.3 centimeters wide and 1 centimeter deep, is original along the top, right, and bottom edges. A large split runs the full length of each plank—at the level of the saints’ and Virgin’s hands in the upper plank and just above their ankles in the lower—interrupting the continuity of the paint surface but not resulting in conspicuous loss of pigment.

When it entered the Gallery’s collection, the dossal had been liberally repainted and its frame provided with a completely new decorative surface (fig. 1). The repaints were removed by Andrew Petryn in a cleaning of 1954, leaving losses unretouched that exposed underpaint, gesso, linen, or wood (fig. 2). Losses were scattered throughout the panel; major losses were particularly obtrusive in the gold ground, which was partially preserved only in the areas of Saint Peter’s halo and the three narrative scenes on the right side of the panel; the back of the Virgin’s throne and the hands of the censing angels above it; and across the full length of the lower plank below its split. The engaged frame was addressed in a second restoration by Andrew Petryn in 1972, when fragments of surviving original decoration on the top and right moldings were exposed, and the bottom and left moldings were left untreated. The cradle was removed by Gianni Marussich in 1999, who replaced it with two battens to reinforce the planarity of the painting support.

A restoration of 2000–2001 by Irma Passeri filled the losses in the panel but completed, in tratteggio, only those that are entirely contained within a field of a single color or whose continuity across different colors could be accurately reconstructed. Profiles bridging areas of which only one could be determined with certainty, such as the back of the Virgin’s throne where it meets the hands of the angel on the right and the Virgin’s halo, were not completed, to avoid optically accentuating the losses around them. These instead were toned back to a neutral color, consistent with the areas of missing gold throughout the panel. The frame moldings were completed with their missing pastiglia appliqués—a floral boss in the center flanked by round bosses, one above and below on the lateral moldings and two to either side on the top and bottom moldings—following the indications of surviving original fragments. A new molding was carved for the left edge to match that on the right. The surfaces of the left and bottom moldings—no original preparatory or final layers survive on the bottom molding—were not reconstructed. Both were completed in the neutral tones matching those of the missing elements of the main pictorial surface, again to avoid lending the impression of a positive shape to adjacent losses.

This panel is among the earliest surviving examples of thirteenth-century Tuscan dossals derived from Byzantine models, with a central image of the Virgin and Child flanked by narrative episodes from the lives of Christ or of the saints. Dominating the center of the composition is a large representation of the enthroned Virgin Galaktotrophousa (“She who nourishes with milk”)—also known as the Madonna Lactans—showing the Virgin nursing the Christ Child. The image, which has been interpreted by scholars in terms of the Eucharistic significance of Mary’s milk as the food of salvation and immortality, appears to have originated in early Byzantine or Coptic Egypt.1 It is later found on eleventh-century Byzantine seals and in the pages of Byzantine illuminated manuscripts, as well as in Roman mosaics, metalwork, and frescoes, but it is rare in Italian panel painting before the fourteenth century. The Yale Virgin is one of a handful of extant representations on panel datable between the second and last quarters of the duecento, and the only one contained within a dossal format. Although no prior Tuscan examples of this particular version of the theme are known,2 it does find a precedent in devotional panels from Rome and the Lazio region, where the type may have been popularized by the twelfth-century mosaic of the enthroned Madonna Lactans on the facade of Santa Maria in Trastevere. Among the most relevant comparisons for the Yale dossal are the so-called Madonna della Catena in the church of San Silvestro al Quirinale in Rome, dated to the second quarter of the thirteenth century, and a slightly later version known as the Madonna della Cantina in the Museo Diocesano, Gaeta.3 In both of these works, as in the Yale dossal, the nursing Child is shown holding a scroll in His left hand while blessing with the other, reflecting the conflation of the lactans motif with a more common type of Virgin Hodegetria.

Directly flanking the enthroned Virgin in the Yale dossal are the full-length figures of Saint Leonard of Noblac, on the left, and Saint Peter, on the right, both identified by inscriptions above their shoulders. Saint Leonard, depicted as a young deacon wearing a scarlet chlamys over a brown dalmatic, holds a book in one hand and blesses with the other. Saint Peter is shown carrying the keys of the Church—originally rendered in gold leaf (now mostly abraded)—looped around his right wrist and raising his right hand in a gesture of blessing while clutching a scroll in his left hand. Standing behind the throne are two angels carrying incense burners (the censer on the right is no longer visible). The central composition is framed on both sides by six narrative quadrants illustrating salient episodes from the life of Saint Peter, in an abbreviated version of the Petrine cycle that finds no equivalent in any Italian altarpiece or devotional panel before the fourteenth century. The scenes, drawn from both biblical and apocryphal sources but not arranged in any proper narrative sequence, are accompanied by a descriptive Latin title elucidating their content. From the top on the left are the Calling of Saints Peter and Andrew (Mark 1:16–17), the Fall of Simon Magus (Pseudo-Marcellus, Passion of the Holy Apostles Peter and Paul, 56), and Saint Peter Freed from Prison (Acts 12:6–8). On the right are Christ Handing the Keys of the Church to Saint Peter (Matthew 16:17–19), Saint Peter Healing the Cripple (Acts 3:1–8), and the Martyrdom of Saints Peter and Paul (Pseudo-Marcellus, Passion of the Holy Apostles Peter and Paul, 58).

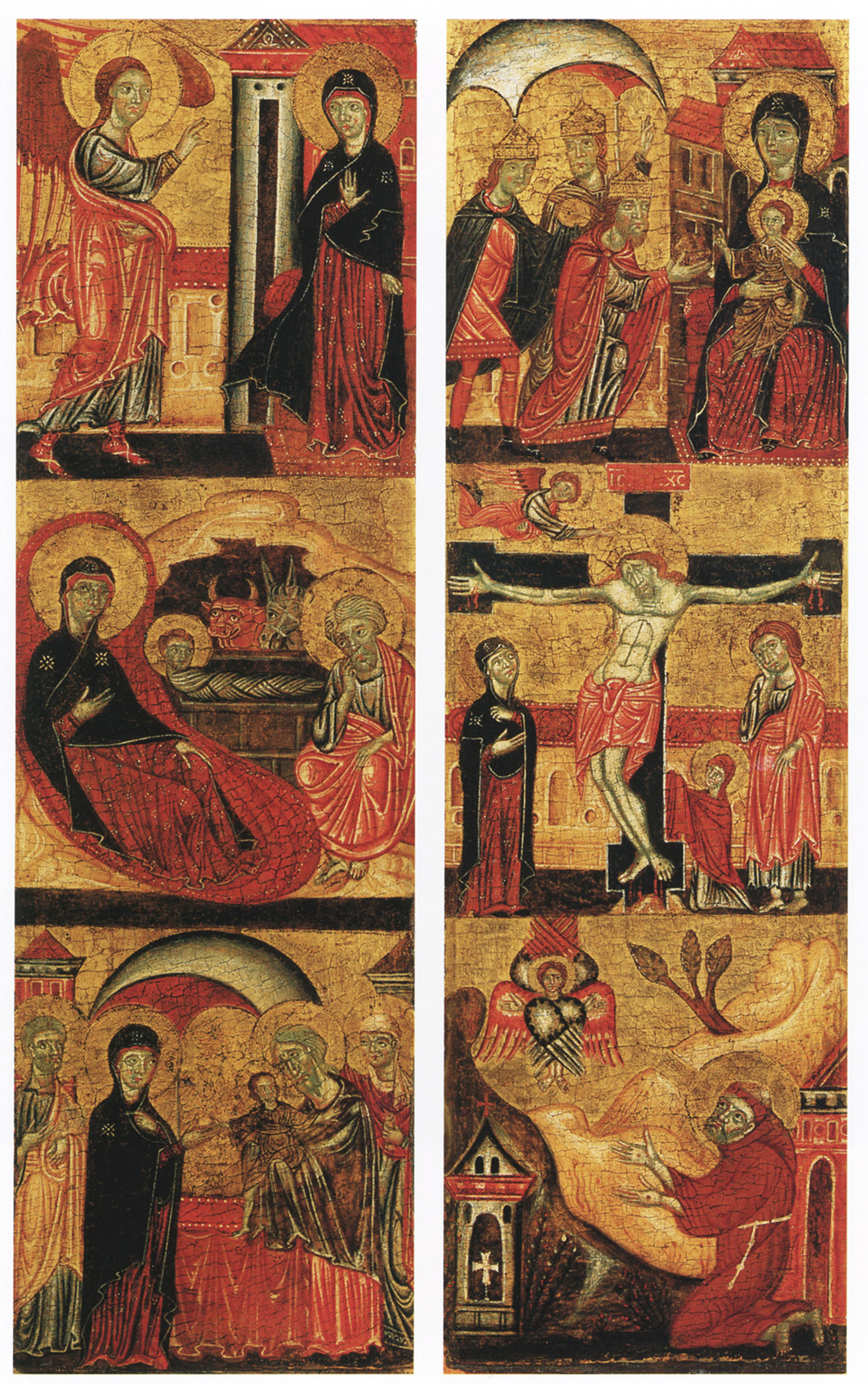

Significantly, the iconography of the Fall of Simon Magus and of the Martyrdom of Saints Peter and Paul departs from that of earlier or near-contemporary Tuscan representations of Saint Peter’s life on panel, as exemplified by the dossals by Meliore in the church of San Leolino at Panzano (fig. 3) or by Guido di Graziano in the Pinacoteca Nazionale, Siena.4 As first pointed out by Gloria Kury Keach, the inclusion of the martyrdom of Saint Paul alongside that of Saint Peter points to a possible dependence on models derived from the lost Petrine cycles in the ancient basilica of Saint Peter in Rome, a church that was the prototype for the decoration of all new foundations dedicated to the saint throughout the eleventh and twelfth centuries.5 Central to Roman Petrine iconography was the emphasis on the spiritual brotherhood between Peter and Paul and their joint mission and martyrdom in Rome, as recounted in apocryphal sources such as the Passion of the Holy Apostles Peter and Paul.6 Written around the fifth or sixth century, this text focuses on the meeting of the two apostles in Rome and their confrontation with Nero and the sorcerer Simon Magus. According to the story, the magician, who had boasted that he could fly, jumped from a tower and was held aloft by demons until the prayers of Peter and Paul caused him to crash to his death, leading Nero to order the execution of the apostles in retaliation. A representation of the Fall of Simon Magus followed by the martyrdoms of the two apostles was included in the lost mosaic decoration of the eighth-century oratory of Pope John VII in Old Saint Peter’s, whose original appearance is recorded by the seventeenth-century drawings of Giacomo Grimaldi. The scenes also follow each other in some tenth- and eleventh-century liturgical manuscripts as well as in the earliest-known Petrine cycles in Tuscany in the Upper Church of Assisi (ca. 1290) and in San Piero in Grado, Pisa (ca. 1300). Common to Roman-derived representations of the Fall of Simon Magus is a close adherence to the apocryphal narrative, which established the supremacy of Peter as the executor of God’s will: “Turning to Peter, Paul said, ‘It is up to me to entreat God on bended knees, and it is up to you to act . . . because you were chosen first by the Lord’” (Passion, 52).7 In these versions, as in the Yale panel, Paul is shown kneeling in prayer next to Peter, whose authority is established by his standing position and commanding gesture as he instructs the devils to let go of the magician.

The Yale dossal was first inserted by Osvald Sirén into a group of images that he initially attributed to a follower of Margaritone d’Arezzo, responsible also for the dossal in the Galleria dell’Accademia, Florence, depicting Mary Magdalen and scenes from her life.8 Richard Offner, who established the Florentine context of the master’s style, subsequently related the Yale panel to a portable triptych in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (fig. 4),9 and a much-damaged Virgin and Child in the Harvard Art Museums, Cambridge, Massachusetts (fig. 5), a work later recognized by Edward Garrison as the central element of a triptych that also included two wings presently in the Museo Civico Amedeo Lia, La Spezia (fig. 6).10 According to Offner, these pictures represented the earliest phase in the career of the so-called Magdalen Master, predating the Accademia panel after which he is named. Offner’s opinion was reiterated by Gertrude Coor-Achenbach in the most comprehensive discussion of the artist’s development and chronology to date.11 Coor-Achenbach placed the Yale panel at the head of a group of works—including the Harvard Virgin and Child and the Metropolitan Museum triptych, although the latter was regarded as a workshop product—which purportedly defined a first, “Florentine-Romanesque” phase in the Magdalen Master’s development.

The observations of Offner and Coor-Achenbach have been unanimously embraced by modern scholarship, which lists the Yale dossal among the canonical early works of the Magdalen Master. Still open to debate, however, is the definition of this painter’s artistic personality and the extent to which the not-entirely homogeneous body of works gathered under his name represents the efforts of a single hand. Whereas scholars such as Angelo Tartuferi have upheld the view of the artist as a unique personality at the head of one of the largest and most successful workshops in Florence in the second half of the thirteenth century, others, following Luisa Marcucci,12 have used the title “Magdalen Master” as a term of convenience to indicate a common style or compagnia of painters working in close association. The absence of any dated paintings among those traditionally assigned to the Magdalen Master, furthermore, has resulted in a variety of opinions regarding the parameters of his activity. Offner viewed the artist’s work as essentially aligned with developments in Florentine painting of the third quarter of the duecento and compared the structure of the Yale panel to those of the Vico l’Abate and Panzano dossals, now attributed, respectively, to Coppo di Marcovaldo and Meliore. Coor-Achenbach, following George Martin Richter,13 significantly extended the length of the artist’s activity to encompass four decades, between 1260 and 1300, and divided his corpus into three perceived stages of evolution, from the “Florentine-Romanesque” phase of the Yale dossal to the “Coppesque-Byzantine” period of the Poppi altarpiece and the “Cimabuesque-Gothic” period of the Accademia’s Magdalen dossal. Giulia Sinibaldi subsequently defined the master’s style more specifically in terms of a union of elements derived from the Bigallo Master, the “Master of Vico l’Abate” (now Coppo), and the Florence Baptistery mosaics, while at the same time noting the affinities—already emphasized by Richter—with the work of Meliore.14 Garrison scaled back the master’s activity to a period between around 1265 and 1290 and dated the Yale dossal to about 1270, shortly after the Harvard Virgin and Child (ca. 1268–70) and the Metropolitan Museum triptych (ca. 1265). A date around 1270 for the Yale dossal was accepted by Charles Seymour, Jr., and Keach, who emphasized, however, the distinction between these works and others under the master’s name and reiterated the notion of a compagnia of different artists operating between around 1250 and 1290. Tartuferi, who regards the Magdalen Master as a single personality, accepted the narrower chronological limits to the artist’s career proposed by Garrison and still associated the Yale, Harvard, and Metropolitan paintings with the “Florentine-Romanesque” phase proposed by Coor-Achenbach—in the seventh decade of the thirteenth century—adducing an eclectic and not-always relevant mix of influences on these works.15 Gaudenz Freuler,16 followed by Daniela Parenti,17 redirected attention to the personality of Meliore and dated both the Yale dossal and the Metropolitan Museum triptych to around 1270, based on perceived stylistic affinities with Meliore’s signed and dated 1271 altarpiece in the Gallerie degli Uffizi, Florence (fig. 7).

The notion that the works currently gathered under the Magadalen Master’s name might be the product of different personalities is confirmed by the noticeable disparities in quality of execution, as well as in figural types, between the Yale panel and the dossal in the Musée des Arts Décoratifs, Paris, which shares the same compositional structure as the Yale painting and is traditionally regarded as the artist’s masterpiece.18 The Paris dossal was placed by Coor-Achenbach in the same early period of the master’s activity as the Yale panel, while subsequent scholars have placed it as much as a decade or more later,19 possibly in an effort to account for its noticeably greater sophistication and advanced spatial and formal concerns. These elements, however, appear less the result of a progressive evolution in style than the manifestation of an altogether more accomplished artist working from the same models.

There is little doubt that the Yale panel and the works most closely related to it are the products of a separate and unique personality. The distinctive idiom of this artist is recognizable in the figural types with regular oval heads, round “goggle eyes,”20 and pronounced noses that also characterize the Harvard and Lia fragments as well as the Metropolitan Museum triptych, despite their differences in scale. A further link among these works, whose homogeneity in concept and execution was already pointed out by Offner, is the identical tooling pattern in the haloes of the subsidiary figures, as revealed by a comparison of the narrative scenes in the Yale dossal with those in the other panels. The perceived similarities of these works to the group of images most closely related to the Magdalen panel are only superficial and do not extend beyond the sharing of compositional formulas and an artisanal quality that is common to the more conservative strain in Florentine painting of the seventh and eighth decades of the thirteenth century, descended from the retardataire culture of the Bigallo Master.

As intuited by previous authors, the closest reference point for the proper assessment of the personality of the artist responsible for the Yale dossal and the works associated with it is the production of Meliore. The influence of the latter is reflected in the often-cited compositional relationship of the Yale panel to the Panzano dossal and in the stylistic affinities, already noted by Freuler and Parenti, among the Yale panel, the Metropolitan Museum triptych, and Meliore’s signed altarpiece in the Uffizi. Possibly even stronger comparisons may be found in the mosaics attributed to Meliore or his circle in the southwest segment of the dome of the Baptistery in Florence, usually dated to the second half of the 1260s;21 and in a little-known fresco cycle in the Ospedale della Misericordia in Prato. The latter was viewed by Parenti as a precedent for the Yale panel and catalogued by Boskovits as the effort of an artist strongly influenced by Meliore and more or less contemporary to the Panzano dossal.22 The similarities to these works seem to confirm that the anonymous author of the Yale dossal and of the images related to it, here christened “Master of the Yale Dossal,” should be sought in Meliore’s circle rather than in that of the Magdalen Master.

Based on the presence of Saint Leonard in the position of honor at the Virgin’s right, Seymour first suggested that the Yale dossal may have been commissioned for the ancient parish church of San Leonardo in Arcetri, built around the eleventh century in the hills outside the Porta San Giorgio in Florence. Although accepted by Luciano Bellosi,23 the possibility of such a provenance has largely been ignored by other scholars, who have pointed to the painting’s emphasis on Saint Peter and his legend. Documentary evidence dating back to the middle of the fourteenth century, however, indicates that, by that date—although presumably beginning much earlier—San Leonardo in Arcetri was a dependency of the now-vanished Florentine basilica of San Pier Scheraggio, whose prior and canons were responsible for the election of its rectors.24 Consecrated in 1068, San Pier Scheraggio was one of the oldest and most important churches in Florence, the place where the gonfalonieri and priors were elected before the construction of the town hall and the site of orations by Dante and Boccaccio.25 The suggestion that a work such as the Yale dossal—if not this very painting—may have provided the visual inspiration for Dante’s poetic references to the image of the Madonna Lactans26 acquires added import given the relationship between San Leonardo and San Pier Scheraggio. It is not out of the question that the canons of San Pier Scheraggio played a role in determining the Petrine iconography of the Yale dossal, whose location on the high altar would have provided a striking visual parallel for the liturgical texts recited on the feasts of Saint Peter.27 —PP

Published References

Jarves, James Jackson. Descriptive Catalogue of “Old Masters” Collected by James J. Jarves to Illustrate the History of Painting from A.D. 1200 to the Best Periods of Italian Art. Cambridge, Mass.: H. O. Houghton, 1860., 42–43, no. 13; Jarves, James Jackson. Art Studies: The “Old Masters” of Italy; Painting. New York: Derby and Jackson, 1861., pl. A (engraving), fig. 2; Sturgis, Russell, Jr. Manual of the Jarves Collection of Early Italian Pictures. New Haven: Yale College, 1868., 25–26, no. 12; W. F. Brown, Boston. Catalogue of the Jarves Collection of Early Italian Pictures. Sale cat. November 9, 1871., 13, no. 12; Rankin, William. Notes on the Collections of Old Masters at Yale University, the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, the Fogg Museum of Harvard University. Wellesley, Mass.: Department of Art, Wellesley College, 1905., 7, no. 12; Sirén, Osvald. A Descriptive Catalogue of the Pictures in the Jarves Collection Belonging to Yale University. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1916., 11–13; Sirén, Osvald. Toskanische Maler im XIII. Jahrhundert. Berlin: P. Cassirer, 1922., 272–75; van Marle, Raimond. The Development of the Italian Schools of Painting. Vol. 1. The Hague: M. Nijhoff, 1923., 336n1, 351–53, 355, fig. 189; Offner, Richard. Italian Primitives at Yale University: Comments and Revisions. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1927., 2, 11–13, fig. 4E; Richter, George Martin. “Megliore di Jacopo and the Magdalen Master.” Burlington Magazine 57, no. 332 (November 1930): 223–36., 230n13, 235; “Handbook: A Description of the Gallery of Fine Arts and the Collections,” special issue, Bulletin of the Associates in Fine Arts at Yale University 5, nos. 1–3 (1931): 1–64., 25; Sandberg-Vavalà, Evelyn. L’iconografia della Madonna col Bambino nella pittura italiana del dugento. Siena: San Bernardino, 1934., 55, no. 162, pl. 25B; Arts of the Middle Ages: A Loan Exhibition. Exh. cat. Boston: Museum of Fine Arts, 1940., 16–17, no. 47, pl. 7; Swarzenski, Georg. “Arts of the Middle Ages.” Bulletin of the Museum of Fine Arts 38, no. 225 (February 1940): 2–7., 2, 7; Guilia Sinibaldi, in Sinibaldi, Giulia, and Giulia Brunetti, eds. Pittura italiana del duecento e trecento: Catalogo della mostra giottesca di Firenze del 1937. Exh. cat. Florence: Sansoni, 1943., 221, 229, 231; “Picture Book Number One: Italian Painting,” special issue, Bulletin of the Associates in Fine Arts at Yale University 15, nos. 1–3 (October 1946): unpag., fig. 2; Comstock, Helen. “The Yale Collection of Italian Paintings.” Connoisseur 118 (September 1946): 45–52., 47; Coor-Achenbach, Gertrude. “A Neglected Work by the Magdalen Master.” Burlington Magazine 89, no. 530 (May 1947): 119–27, 29., 120n12, 126n38; Garrison, Edward B. Italian Romanesque Panel Painting: An Illustrated Index. Florence: Leo S. Olschki, 1949., 142, no. 366; Steegmuller, Francis. The Two Lives of James Jackson Jarves. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1951., 293; Kaftal, George. Iconography of the Saints in Tuscan Painting. Florence: Sansoni, 1952., col. 627, no. 186, fig. 723; Seymour, Charles, Jr. Early Italian Paintings in the Yale University Art Gallery. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1970., 9–11, no. 1; Fredericksen, Burton B., and Federico Zeri. Census of Pre-Nineteenth-Century Italian Paintings in North American Public Collections. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1972., 599; Gloria Kury Keach, in Seymour, Charles, Jr., et al. Italian Primitives: The Case History of a Collection and Its Conservation. Exh. cat. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1972., 9–10, no. 1, fig. 1a; Ritchie, Andrew Carnduff, and Katharine B. Neilson. Selected Paintings and Sculpture from the Yale University Art Gallery. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1972., no. 1; Tartuferi, Angelo. “Pittura fiorentina del duecento.” In La pittura in Italia: Il duecento e il trecento, ed. Enrico Castelnuovo, 1:267–82. Milan: Electa, 1986., 276; Castelnuovo, Enrico, ed. La pittura in Italia: Il duecento e il trecento. 2 vols. Milan: Electa, 1986., 2:607; Marques, Luiz C. La peinture du duecento en Italie centrale. Paris: Picard, 1987., 288; Offner, Richard. A Critical and Historical Corpus of Florentine Painting. Sec. 3, vol. 2, Elder Contemporaries of Bernardo Daddi. Ed. Miklós Boskovits. Florence: Giunti, 1987., 284n2; Tartuferi, Angelo. La pittura a Firenze nel duecento. Florence: Alberto Bruschi, 1990., 43, 92, fig. 142; Freuler, Gaudenz. Manifestatori delle cose miracolose: Arte italiana del ’300 e ’400 da collezioni in Svizzera e nel Lichtenstein. Exh. cat. Lugano, Switzerland: Fondazione Thyssen-Bornemisza, 1991., 26; Kenney, Elise K., ed. Handbook of the Collections: Yale University Art Gallery. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1992., 131; Parenti, Daniela. “Note in margine a uno studio sul duecento fiorentino.” Paragone 43, nos. 505–7 (1992): 51–58., 54; Mazzaro, Jerome. “Dante and the Image of the ‘Madonna Allattante.’” Dante Studies 114 (1996): 95–111., 98, 111, pl. 2; Bellosi, Luciano. Cimabue. Milan: F. Motta, 1998., 4; Dean, Clay. A Selection of Early Italian Paintings from the Yale University Art Gallery. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 2001., 13, 16–17, no. 1; Garland, Patricia Sherwin. “Recent Solutions to Problems Presented by the Yale Collection.” In Early Italian Paintings: Approaches to Conservation; Proceedings of a Symposium at the Yale University Art Gallery, April 2002, ed. Patricia Sherwin Garland, 54–70. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 2003., 64, fig. 3.9, pl. 4; Finch, Margaret. “St. Peter and the Brancacci Chapel.” Apollo 160 (September 2004): 66–75., 69–70, 71n27, fig. 5; Daniela Parenti, in Tartuferi, Angelo, and Mario Scalini, eds. L’arte a Firenze nell’età di Dante (1250–1300). Exh. cat. Florence: Giunti, 2004., 100; Smith, Elizabeth. “An American in Medieval Paris: The Impact of Europe on Early American Collectors of Medieval Art.” Acta ad Archaeologiam et Artium Historiam Pertinentia, n.s., 18, no. 4 (2004): 323–44., 333, fig. 5; Angelo Tartuferi, in Chiodo, Sonia, and Serena Padovani. Italian Paintings from the 14th to 16th Century. The Alana Collection 3. Florence: Mandragora, 2014., 3:179, 182

Notes

-

Since Mary, as a virgin, would have been incapable of producing milk, the image was meant to highlight the divine nature of Christ as he received nourishment from God through her. The author is grateful for the summary of the literature on the Virgin Galaktotrophousa provided by Kimberly Staking in her seminar paper for the University of Maryland; see Staking, Kimberly. “Byzantine Sources, Political Resonance and Eucharistic Symbolism in the Galaktotrophousa Dossal by the Magdalen Master.” Seminar paper, University of Maryland, December 16, 1996. Copy in curatorial files, Department of European Art, Yale University Art Gallery.. The type’s origins have been much debated by scholars. See Bolman, Elizabeth S. “The Coptic Galaktotrophousa Revisited.” In Coptic Studies on the Threshold of a New Millennium: Proceedings of the Seventh International Congress of Coptic Studies, ed. Mat Immerzeel and Jacques van der Vliet, 2:1173–84. Leuven, Belgium: Peeters, 2004., 1173–84; and, more recently, Higgins, Sabrina C. “Divine Mothers: The Influence of Isis on the Virgin Mary in Egyptian Lactans-Iconography.” Journal of the Canadian Society for Coptic Studies 3–4 (2012): 71–90., 71–90. ↩︎

-

The only other Tuscan duecento example, a Pisan dossal fragment in the Museo Nazionale di San Matteo, Pisa, is later in date and presents a variant of the iconography, with a three-quarter-length Virgin and the Child clutching her finger and breast; see Garrison, Edward B. Italian Romanesque Panel Painting: An Illustrated Index. Florence: Leo S. Olschki, 1949., 232, no. 647. ↩︎

-

For these works, see Leone, Giorgio, ed. Tavole miracolose: Le icone medievali di Roma e del Lazio del Fondo edifici di culto. Exh. cat. Rome: L’Erma di Bretschneider, 2012., 50–52, no. 1.5; and Marchionibus, Maria Rosaria. “La Madonna della Cantina e il culto della Virgo Lactans nel territorio della diocesi di Gaeta.” In Gaeta medievale e la sua cattedrale, ed. Mario D’Onofrio and Manuela Gianandrea, 213–24. Rome: Campisano, 2018., 213–24. ↩︎

-

Inv. no. 15. ↩︎

-

Gloria Kury Keach, in Seymour, Charles, Jr., et al. Italian Primitives: The Case History of a Collection and Its Conservation. Exh. cat. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1972., 9–10, no. 1. See also Kessler, Herbert L. “L’antica basilica di San Pietro come fonte e ispirazione per la decorazione delle chiese medievali.” In Fragmenta picta: Affreschi e mosaici staccati del medioevo romano, ed. Maria Andaloro et al., 45–110. Rome: Àrgos, 1989., 45–64. For the evolution of the iconography of Petrine cycles, see Bisconti, F., and S. Manacorda. “Pietro, Santo.” In Enciclopedia dell’arte medievale (1998). https://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/santo-pietro_(Enciclopedia-dell’-Arte-Medievale)/.. ↩︎

-

Eastman, David L. The Ancient Martyrdom Accounts of Peter and Paul. Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature Press, 2015., 221–69. ↩︎

-

Viscontini, Manuela. “La figura di Pietro negli atti degli apostoli: Un caso particolare, La Capella Palatina di Palermo.” In La figura di San Pietro nelle fonti del medioevo, ed. Loredana Lazzari and Anna Maria Valente Bacci, 457–83. Textes et études du Moyen Âge 17. Louvain-la-Neuve, Belgium: Fédération Internationale des Instituts d’Études Médiévales, 2001., 457–83, esp. 472–74. ↩︎

-

Inv. no. 1890 n. 8466. See Sirén, Osvald. A Descriptive Catalogue of the Pictures in the Jarves Collection Belonging to Yale University. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1916., 11–13; and Sirén, Osvald. Toskanische Maler im XIII. Jahrhundert. Berlin: P. Cassirer, 1922., 272–75. ↩︎

-

Offner, Richard. Italian Primitives at Yale University: Comments and Revisions. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1927., 2, 11–13. ↩︎

-

See Garrison, Edward B. Italian Romanesque Panel Painting: An Illustrated Index. Florence: Leo S. Olschki, 1949., 142, no. 366; and Zeri, Federico, and Andrea G. De Marchi. Dipinti: La Spezia, Museo Civico Amedeo Lia. Cataloghi del Museo Civico Amadeo Lia 3. Milan: Silvana, 1997., 204–5, nos. 87–88. ↩︎

-

Coor-Achenbach, Gertrude. “A Neglected Work by the Magdalen Master.” Burlington Magazine 89, no. 530 (May 1947): 119–27, 29., 119–27, 129. ↩︎

-

Marcucci, Luisa. Gallerie nazionali di Firenze: I dipinti toscani del secolo XIII, Scuole bizantine e russe dal secolo XII al secolo XVIII. Cataloghi dei musei e gallerie d’Italia. Rome: Istituto Poligrafico dello Stato, 1958., 49–56. ↩︎

-

Richter, George Martin. “Megliore di Jacopo and the Magdalen Master.” Burlington Magazine 57, no. 332 (November 1930): 223–36., 235. ↩︎

-

Giulia Sinibaldi, in Sinibaldi, Giulia, and Giulia Brunetti, eds. Pittura italiana del duecento e trecento: Catalogo della mostra giottesca di Firenze del 1937. Exh. cat. Florence: Sansoni, 1943., 231. ↩︎

-

Tartuferi’s allusion to the Master of Crucifix 432, named after a cross in the Gallerie degli Uffizi, Florence, seems chronologically far-reaching, and that to the Rovezzano Master appears misplaced from a stylistic point of view. Miklós Boskovits, who only accepted one other panel beside the Rovezzano Virgin as a work by the same hand, distinguished the retardataire qualities of this painter from those of the Bigallo Master, noting that “the manner of this author appears actually more archaic than archaizing, and it is difficult to find a place for him within the general panorama of Florentine Duecento painting”; Boskovits, Miklós, with Ada Labriola and Angelo Tartuferi. A Critical and Historical Corpus of Florentine Painting. Sec. 1, vol. 1, The Origins of Florentine Painting, 1100–1270. Trans. Robert Erich Wolf. Florence: Giunti, 1993., 33. ↩︎

-

Freuler, Gaudenz. Manifestatori delle cose miracolose: Arte italiana del ’300 e ’400 da collezioni in Svizzera e nel Lichtenstein. Exh. cat. Lugano, Switzerland: Fondazione Thyssen-Bornemisza, 1991., 26. ↩︎

-

Daniela Parenti, in Tartuferi, Angelo, and Mario Scalini, eds. L’arte a Firenze nell’età di Dante (1250–1300). Exh. cat. Florence: Giunti, 2004., 100. ↩︎

-

Inv. PE 76. ↩︎

-

Daniela Parenti, in Tartuferi, Angelo, and Mario Scalini, eds. L’arte a Firenze nell’età di Dante (1250–1300). Exh. cat. Florence: Giunti, 2004., 98–99, no. 9. ↩︎

-

Offner, Richard. Italian Primitives at Yale University: Comments and Revisions. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1927., 12. ↩︎

-

Miklós Boskovits, who most recently assigned some of the figures in the mosaics to Meliore himself, compared them to the Panzano dossal and Meliore’s Virgin and Child in the Museo di Arte Sacra, Certaldo, with a date “around or shortly before 1270”; Boskovits, Miklós. A Critical and Historical Corpus of Florentine Painting. Sec. 1, vol. 2, The Mosaics of the Baptistery of Florence. Florence: Giunti, 2007., 153, 156–57, pls. XXI–XXII (with previous bibliography). Based on the condition of the mosaics in the second tier and overall result of previous restorations, Anna Maria Giusti preferred to classify these images as belonging more generally to the stylistic milieu of Meliore; see Giusti, Anna Maria. “The Mosaics of the Gallery Tribunes and Parapets, and on the Drum of the Vaults.” In Il battistero di San Giovanni a Firenze, ed. Antonio Paolucci, 2:281–342. Modena: Panini, 1994., 309, 521–22. The relationship of the Yale dossal to the Baptistery mosaics was already noted by Gloria Kury Keach, in Seymour, Charles, Jr., et al. Italian Primitives: The Case History of a Collection and Its Conservation. Exh. cat. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1972., 10. ↩︎

-

Parenti, Daniela. “Note in margine a uno studio sul duecento fiorentino.” Paragone 43, nos. 505–7 (1992): 51–58., 54; and Boskovits, Miklós, with Ada Labriola and Angelo Tartuferi. A Critical and Historical Corpus of Florentine Painting. Sec. 1, vol. 1, The Origins of Florentine Painting, 1100–1270. Trans. Robert Erich Wolf. Florence: Giunti, 1993., 136, pls. LXIII (1–6). ↩︎

-

Bellosi, Luciano. Cimabue. Milan: F. Motta, 1998., 4. ↩︎

-

Moreni, Domenico. Notizie istoriche dei contorni di Firenze. Pt. 5, Dalla Porta a S. Niccolò fino alla Pieve di S. Piero a Ripoli. Florence: n.p., 1794., 21. For a complete history of the church, see Botteri Landucci, Laura, and Gilberto Dorini. La chiesa di San Leonardo in Arcetri. Florence: Becocci, 1996.. ↩︎

-

Richa, Giuseppe. Notizie istoriche delle chiese fiorentine divise ne’suoi quartieri. Vol. 2, Del quartiere di Santa Croce: Parte seconda. Florence: Pietro Gaetano Viviani, 1755., 1–32. Tradition states that Dante and others spoke from the famous Romanesque pulpit transferred from San Pier Scheraggio to San Leonardo in Arcetri in 1782, after the suppression of San Piero. ↩︎

-

Mazzaro, Jerome. “Dante and the Image of the ‘Madonna Allattante.’” Dante Studies 114 (1996): 95–111., 98. ↩︎

-

For the relationship between Petrine iconography and readings for the feasts of Saint Peter, see Viscontini, Manuela. “La figura di Pietro negli atti degli apostoli: Un caso particolare, La Capella Palatina di Palermo.” In La figura di San Pietro nelle fonti del medioevo, ed. Loredana Lazzari and Anna Maria Valente Bacci, 457–83. Textes et études du Moyen Âge 17. Louvain-la-Neuve, Belgium: Fédération Internationale des Instituts d’Études Médiévales, 2001., 478–80. ↩︎