Satinover Galleries, New York, by 1920; Robert Lehman (1891–1969), New York, 1920

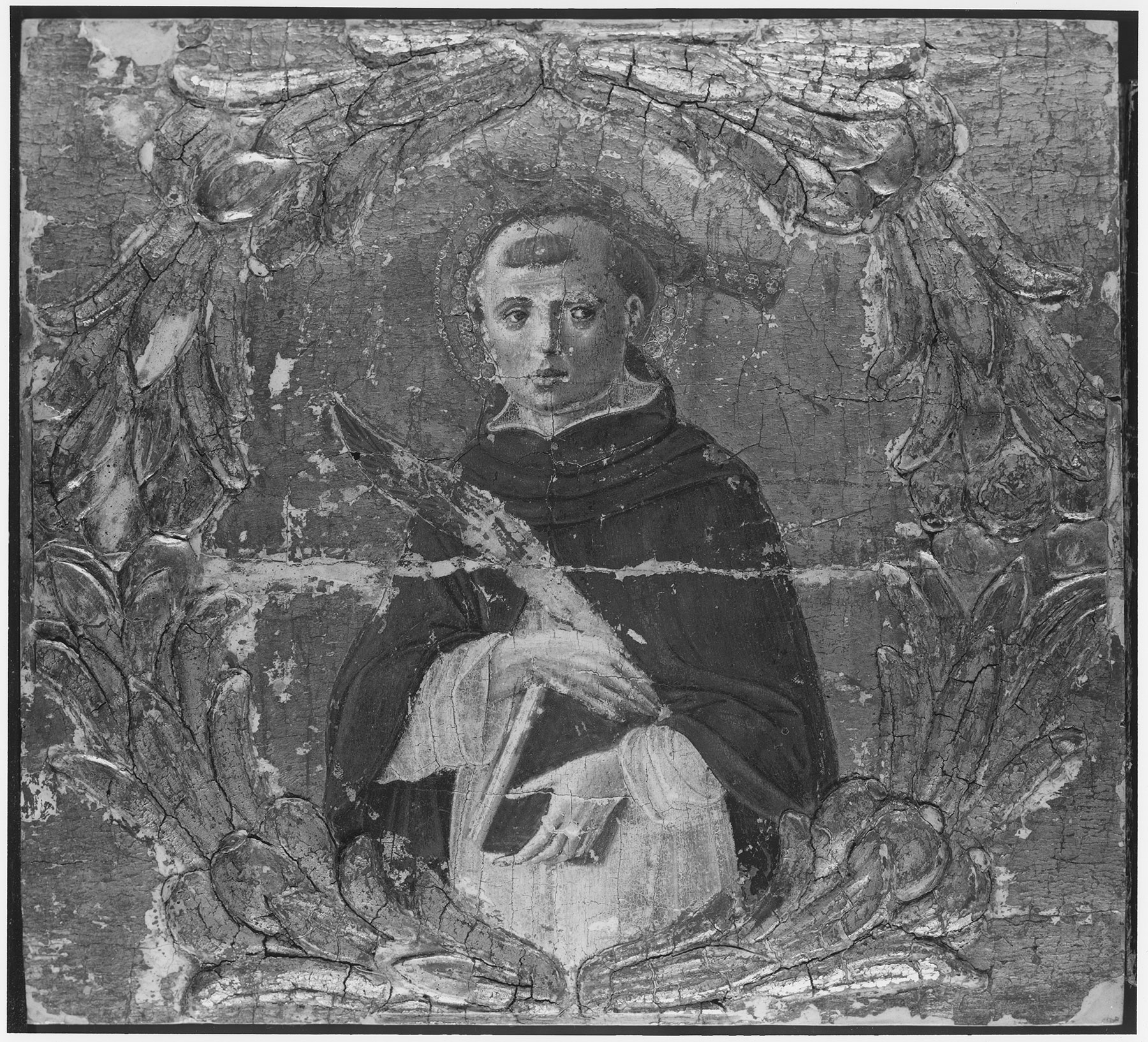

The panel, of a horizontal wood grain with a moderate convex warp, has been thinned to a depth varying from 4 millimeters at the bottom, 10 millimeters at the center, and 7 millimeters at the top, cradled, and waxed. A prominent split approximately 10.5 centimeters from the bottom edge runs the full length of the panel, with smaller partial splits appearing at 5.5, 15, and 19 centimeters from the bottom edge. The gilding and paint surfaces have suffered minimal abrasion but are interrupted by numerous flaking losses that have been liberally retouched, including regilding over new bolus during a treatment in 1999. The largest losses follow the central split in the panel, but smaller losses, visible in photographs taken after cleaning by Andrew Petryn in 1965–68 (fig. 1), are not restricted to any one area of the panel. The silver knife is entirely an invention of the 1999 restoration, following incisions in the gold ground indicating its original profile, as is the green palm frond held in the saint’s right hand.

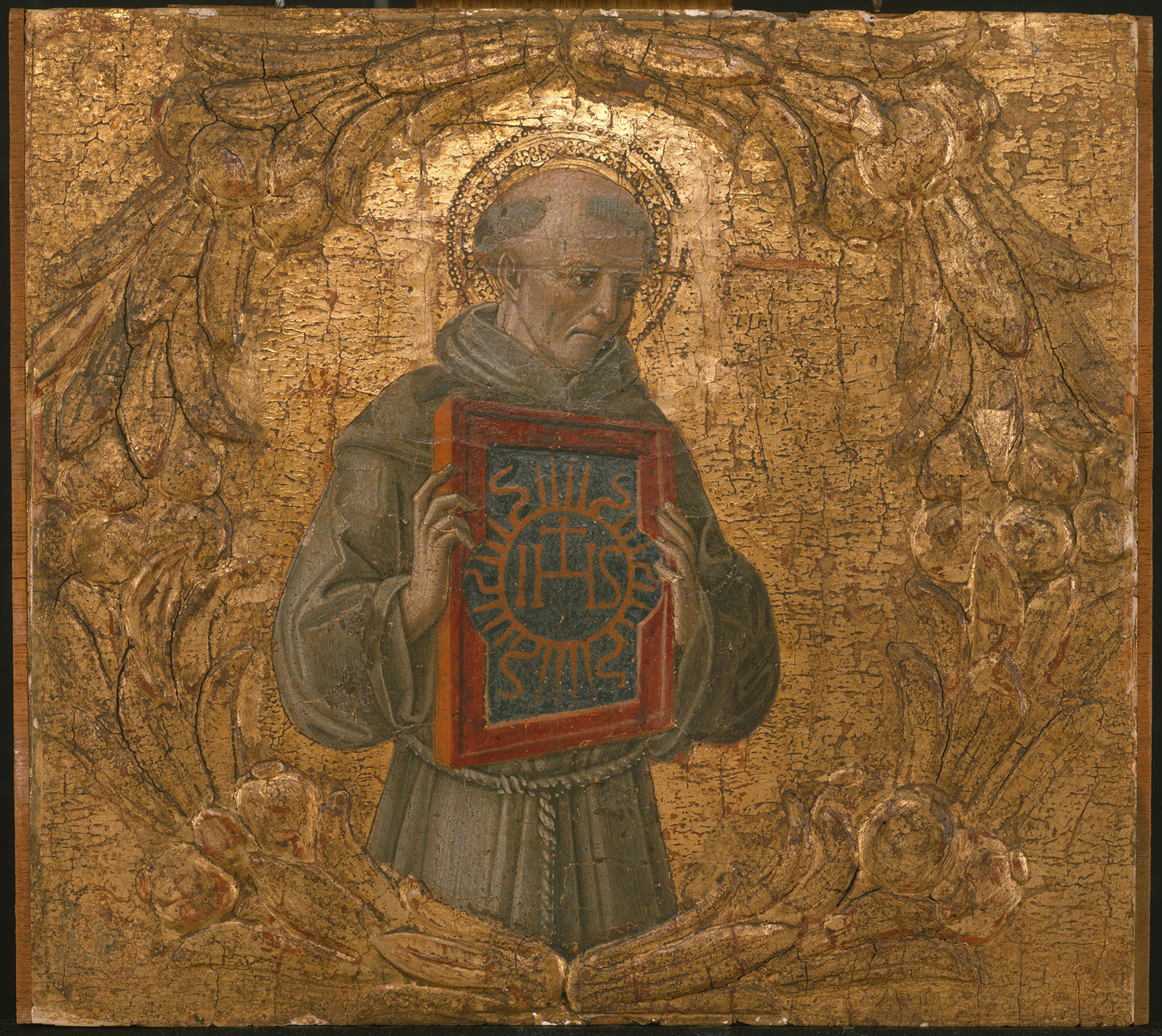

All authors to have considered this painting agree in attributing it to Benvenuto di Giovanni, and those who have discussed its date all place it in the mid-1470s. Burton Fredericksen and Darrell Davisson compared it to Benvenuto’s biccherna cover of 1474, portraying an Allegory of Good Government,1 while Charles Seymour, Jr., and Maria Cristina Bandera dated it ca. 1475, relating it to the Montepertuso altarpiece, now in Vescovado di Murlo.2 John Pope-Hennessy and the present author published five companion panels once framed together with the Yale Saint Peter Martyr, arranged in two sets of three, when all six were purchased from the Satinover Galleries by Robert Lehman in October 1920.3 Each of the six panels portrayed a single figure in an identical bust-length format enclosed within a pastiglia garland. The six panels are:

-

Saint Bernardino, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (fig. 2);

-

the present panel;

-

Saint Francis, Museum of Fine Arts, Houston (fig. 3);

-

Saint Dominic, formerly Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City;

-

Salvator Mundi, formerly Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City;

-

Saint Anthony of Padua, formerly A. Merriman Pfaff collection.4

As all six figures are painted on panel supports with a horizontal wood grain, it is generally presumed that together they formed the predella to a large altarpiece. In such a context, the Salvator Mundi would invariably occupy a central position, implying that there cannot have been an even number of figures originally and that at least one additional figure is missing. The overall length of such a predella, if only one figure were missing, would have been greater than 180 centimeters, considerably more if allowance is made for wood lost between each figure implied by the cropping of their pastiglia garlands. If more than one figure were missing—possibly an additional set of three, as they were framed in the early twentieth century—the overall length would have been greater than 240 centimeters, possibly as much as 270 centimeters. Carolyn Wilson and Bandera, assuming that only a single figure from the series is lost, suggest that the altarpiece to which this putative predella is likely to have been attached is the Borghesi altarpiece in San Domenico, Siena (fig. 4).5 This proposal was bolstered by analogies of style—the Borghesi altarpiece is widely presumed to have been painted in the mid- or late 1470s, in any event before 1478—but rested primarily on iconographic considerations, as the predella includes the principle Dominican saints who are notably absent from the main panel of the altarpiece. Both authors additionally propose a series of six full-length standing saints now divided between the collections of the New Orleans Museum of Art and the Samek Art Museum, Bucknell University, Lewisburg, Pennsylvania, that would have decorated the altarpiece’s framing pilasters.6 Included among these six pilaster figures are a Dominican saint, possibly Saint Thomas Aquinas, the only major Dominican not represented in the predella, and a Sienese Dominican, the Blessed Ambrogio Sansedoni.

Although it has not been questioned in recent scholarship, several factors militate against this reconstruction. Chief among these is the presence of three Franciscans among the six known predella figures, outnumbering Dominicans in the series as it is currently preserved. Also, even if allowance is made for only a single missing figure—presumably either another Franciscan or another Dominican—the total width of the predella exceeds the width of the main panel of the Borghesi altarpiece, which is 189 centimeters. Bandera’s reconstruction, which allowed for spacing between the pastiglia surrounds of the saints, presumed that the predella extended beneath the framing pilasters, but such a format is unprecedented in Sienese altarpiece design, nor does it form a precedent for later examples. There is, furthermore, a net distinction of style between the predella figures, correctly associated by Fredericksen and Davisson with Benvenuto’s work in the early 1470s, and the pilaster saints, more closely related to paintings by Benvenuto datable to the late 1470s or early 1480s. It should be observed, however, that a similar distinction in style obtains within the Borghesi altarpiece itself. While the main panel is indeed consonant with Benvenuto’s paintings of the early or mid-1470s, the lunette compares more effectively with works putatively of the 1480s. As it is also too large for the panel below it and has obviously been cut to fit into this context, it is possible that the lunette is a surviving remnant of Benvenuto di Giovanni’s altarpiece for the nearby Bellanti Chapel in San Domenico, on which he is documented as working in 1483.7 It is at least conceptually possible that the New Orleans/Bucknell pilaster saints also derive from the Bellanti altarpiece and that the Yale panel and its associated predella fragments may instead have been part of the original commission for the Borghesi altar. The only argument for bringing the two series together in a single reconstruction is that none of the Dominican saints is duplicated between them, but there is no possibility of knowing whether the missing panel or panels from the predella might have represented Saint Thomas Aquinas, or Saint Louis of Toulouse (making a Franciscan provenance far more likely than a Dominican one), or another Franciscan or Dominican figure.

Divorced from its lunette, it is no longer necessary to presume that the main panel of the Borghesi altarpiece was painted as late as 1476–78, as is currently maintained. While a document of 1478 may safely be interpreted as indicating a terminus ante quem for its execution, the chapel in which it stood was founded in 1467, and the commission for the altarpiece could have been received at any time in the ensuing decade.8 The figure style and spatial exaggerations within this painting represent a middle term in the evolution of Benvenuto di Giovanni’s pictorial vocabulary, between, on the one hand, the altarpieces of the Annunciation in Sinalunga and Nativity in Volterra, both of 1470, and, on the other, the Montepertuso altarpiece of 1475.9 A date in the first half of the decade would permit greater confidence in accepting the identification of the Yale panel and its companions as part of the Borghesi predella, as Fredericksen and Davisson were correct in noting the relationship between the latter and Benvenuto’s dated biccherna cover of 1474.10 The objections noted above, however, remain valid, particularly the objection that so many Franciscan saints are unprecedented in the context of a predella to a prominent altarpiece in a major Dominican establishment. Furthermore, the document of 1478 that cites the Borghesi altarpiece adduces it as a model to be followed by Matteo di Giovanni in his commission for another altarpiece in San Domenico, yet neither that altarpiece nor any other Sienese altarpiece or altarpiece fragment incorporates pastiglia garlands isolating the figures, as in this series. The question must at least be posed whether this series was, in fact, a predella or whether it might have formed part of the architectural decoration in a different, and not necessarily Dominican, context.

No physical clues embedded within the panels themselves offer additional insight into the possible nature of such an alternative context. The combination of Franciscan and Dominican saints might suggest a confraternal rather than ecclesiastical or conventual origin, but no extant models exist in situ that could provide meaningful parallels. Dominican chapter houses were frequently decorated with bust-length or half-length portraits of Dominican saints and blesseds surrounding door or window frames, and such might have been the function of the present series, analogous to portraits of antique or modern heroes that sometimes decorated the cornice moldings in Lombard palaces. Additionally, although it is impossible to know the identity or identities of the saints who might be missing from the series, it may be significant that the principle Sienese Dominican saint, Catherine of Siena, is absent. This may be a function of all the existing saints being male, but it may also be an indication that the series was not intended for a Sienese patron. While Saint Bernardino was Sienese, he was widely venerated throughout Italy. An oratory dedicated to him is one of the chief Franciscan monuments in Perugia, for example, and it is in Perugia rather than Siena that bust-length saints enclosed in painted (although not pastiglia) garlands are encountered at approximately this date. Pietro Perugino’s Saint Peter (fig. 5) in the Landesmuseum, Hannover, Germany, must be exactly coeval with the Yale Saint Peter Martyr and its companions, and it may well have derived from a related series of images. —LK

Published References

Berenson, Bernard. Italian Pictures of the Renaissance: A List of the Principal Artists and Their Works with an Index of Places. Oxford: Clarendon, 1932., 77; Berenson, Bernard. Pitture italiane del Rinascimento: Catalogo dei principali artisti e delle loro opera. Trans. Emilio Cecchi. Milan: Ulrico Hoepli, 1936., 66; van Marle, Raimond. The Development of the Italian Schools of Painting. Vol. 16. The Hague: M. Nijhoff, 1937., 416; Fredericksen, Burton B., and Darrell D. Davisson. Benvenuto di Giovanni, Girolamo di Benvenuto: A Summary Catalogue of Their Paintings in America. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 1966., 25, 27, 35, fig. 12; Berenson, Bernard. Italian Pictures of the Renaissance, A List of the Principal Artists and Their Works with an Index of Places: Central Italian and North Italian Schools. 3 vols. London: Phaidon, 1968., 1:40; Seymour, Charles, Jr. Early Italian Paintings in the Yale University Art Gallery. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1970., 188, 318, no. 140; Fredericksen, Burton B., and Federico Zeri. Census of Pre-Nineteenth-Century Italian Paintings in North American Public Collections. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1972., 601; Bandera, Maria Cristina. “Qualche osservazione su Benvenuto di Giovanni.” Antichità viva 13, no. 1 (1974): 3–17., 8–9, fig. 16; Pope-Hennessy, John, and Laurence Kanter. The Robert Lehman Collection. Vol. 1, Italian Paintings. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1987., 164; Wilson, Carolyn C. Italian Paintings, XIV–XVI Centuries, in the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. Houston: Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, 1996., 180–88, fig. 16.3 (panel m); Bandera, Maria Cristina. Benvenuto di Giovanni. Milan: Federico Motta, 1999., 101, 104–6, 228–29, no. 39

Notes

-

Fredericksen, Burton B., and Darrell D. Davisson. Benvenuto di Giovanni, Girolamo di Benvenuto: A Summary Catalogue of Their Paintings in America. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 1966., 25. ↩︎

-

Seymour, Charles, Jr. Early Italian Paintings in the Yale University Art Gallery. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1970., 188, no. 140; and Bandera, Maria Cristina. “Qualche osservazione su Benvenuto di Giovanni.” Antichità viva 13, no. 1 (1974): 3–17., 8–9, fig. 16. ↩︎

-

Pope-Hennessy, John, and Laurence Kanter. The Robert Lehman Collection. Vol. 1, Italian Paintings. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1987., 164. ↩︎

-

The Saint Dominic and Salvator Mundi were both sold at Christie’s, New York, June 6, 1984, lot 27. The locations of those panels and that of the Saint Anthony of Padua are all currently unknown. ↩︎

-

Wilson, Carolyn C. Italian Paintings, XIV–XVI Centuries, in the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. Houston: Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, 1996., 180–88, fig. 16.3 (panel m); and Bandera, Maria Cristina. Benvenuto di Giovanni. Milan: Federico Motta, 1999., 101, 104–6. ↩︎

-

Saint John the Baptist; Saint Margaret; Blessed Ambrogio Sansedoni, New Orleans Museum of Art, inv. no. 61.69a, b, c, http://www.noma.org/collection/st-john-the-baptist-st-margaret-the-blessed-ambrose-sansedoni/; and Saint Jerome; Dominican Saint; Bishop Saint, Samek Art Museum, Bucknell University, Lewisburg, Penna., inv. no. 1961.K.1744A, https://collection.museum.bucknell.edu/Detail/objects/40892. ↩︎

-

Milanesi, Gaetano. Documenti per la storia dell’arte senese. 3 vols. Siena: n.p., 1854–56., 3:79; and Borghesi, S., and L. Banchi. Nuovi documenti per la storia dell’arte senese. Siena: Enrico Torrini, 1898., 330n165. ↩︎

-

Seidel, Max. “Sozialgeschichte des Sieneser Renaissance-Bildes: Studien zu Francesco di Giorgio, Neroccio de Landi, Benvenuto di Giovanni, Matteo di Giovanni und Bernardino Fungai.” Städel-Jahrbuch, n.s., 12 (1989): 71–138., 76–83. Seidel’s hypothesis was also reported by the present author, in Christiansen, Keith, Laurence Kanter, and Carl Brandon Strehlke. Painting in Renaissance Siena, 1420–1500. Exh. cat. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1988., 302, 305, 306n1. ↩︎

-

Kanter, Laurence. Italian Paintings in the Museum of Fine Arts Boston. Volume 1, 13th–15th Century. Boston: Museum of Fine Arts, 1994., 203n2. Maria Cristina Bandera (in Bandera, Maria Cristina. Benvenuto di Giovanni. Milan: Federico Motta, 1999., 226) noted a manuscript opinion by the present author that the Borghesi altarpiece should be dated 1473–74. There does not now seem to be any reason to rethink that contention. ↩︎

-

Fredericksen, Burton B., and Darrell D. Davisson. Benvenuto di Giovanni, Girolamo di Benvenuto: A Summary Catalogue of Their Paintings in America. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 1966., 25. ↩︎