Galerie d’Atri, Paris, by 1940(?);1 Andrew F. Petryn (1918–2013), New Haven, by 1967(?)2

All three members of the triptych are constructed of panels with a vertical wood grain and retain their original thickness: 2.2 centimeters in the case of the center panel and 1 centimeter in the case of each wing. All three are surrounded by engaged frame moldings 8 millimeters thick and are joined to one another by their original wire hinges. A slight convex warp to the center panel has provoked a minor split 8 centimeters from its right edge at the bottom and has also split the bottom engaged molding. The gilding and paint surfaces in all three panels are beautifully preserved. There are two small losses in the center panel in the front of the dais beneath the Virgin’s throne and minor flaking in glazes over the silver leaf and in the shaded right side of God the Father at the top. The figures of Saints Francis and Bernardino are slightly rubbed. Both wings are painted on their reverse with a green-and-white textile pattern that is not original. The back of the center panel is covered with a bluish-green wash that is also not original.

This triptych—of a notably fine level of craftsmanship in its carpentry, gilding, and painting, if not of equal merit for its artistic inventiveness—repeats a compositional formula well known in Sienese painting since the fourteenth century. The central panel shows the Virgin and Child Enthroned with two angels holding a crown above the Virgin’s head, a grouping loosely reminiscent of Sassetta’s Madonna of Humility installed in the Palazzo Pubblico in Siena in 1438 (see Giovanni di Paolo, Virgin and Child with Saints Bartholomew and Jerome, fig. 1).3 Full-length figures of Saints Peter and Jerome stand in front of the throne, flanking the Virgin on the left and right, respectively, while a half-length figure of the blessing God the Father appears in a mandorla of engraved lines in the pinnacle of the panel. The wings show two of the patron saints of Siena and two Franciscan saints, turned toward the figures in the center. On the left are Saint Ansanus, carrying a martyr’s palm and the Sienese Balzana, with Saint Francis kneeling before him in a pose usually encountered in scenes of the Stigmatization. On the right are Saint Sabinus, holding a banner with a rampant lion in gold on red, symbol of the Capitano del Popolo of Siena, with Saint Bernardino kneeling before him in a pose mirroring that of Saint Francis. The gables of the wings are filled with smaller-scale figures of the Annunciatory Angel and the Virgin Annunciate.

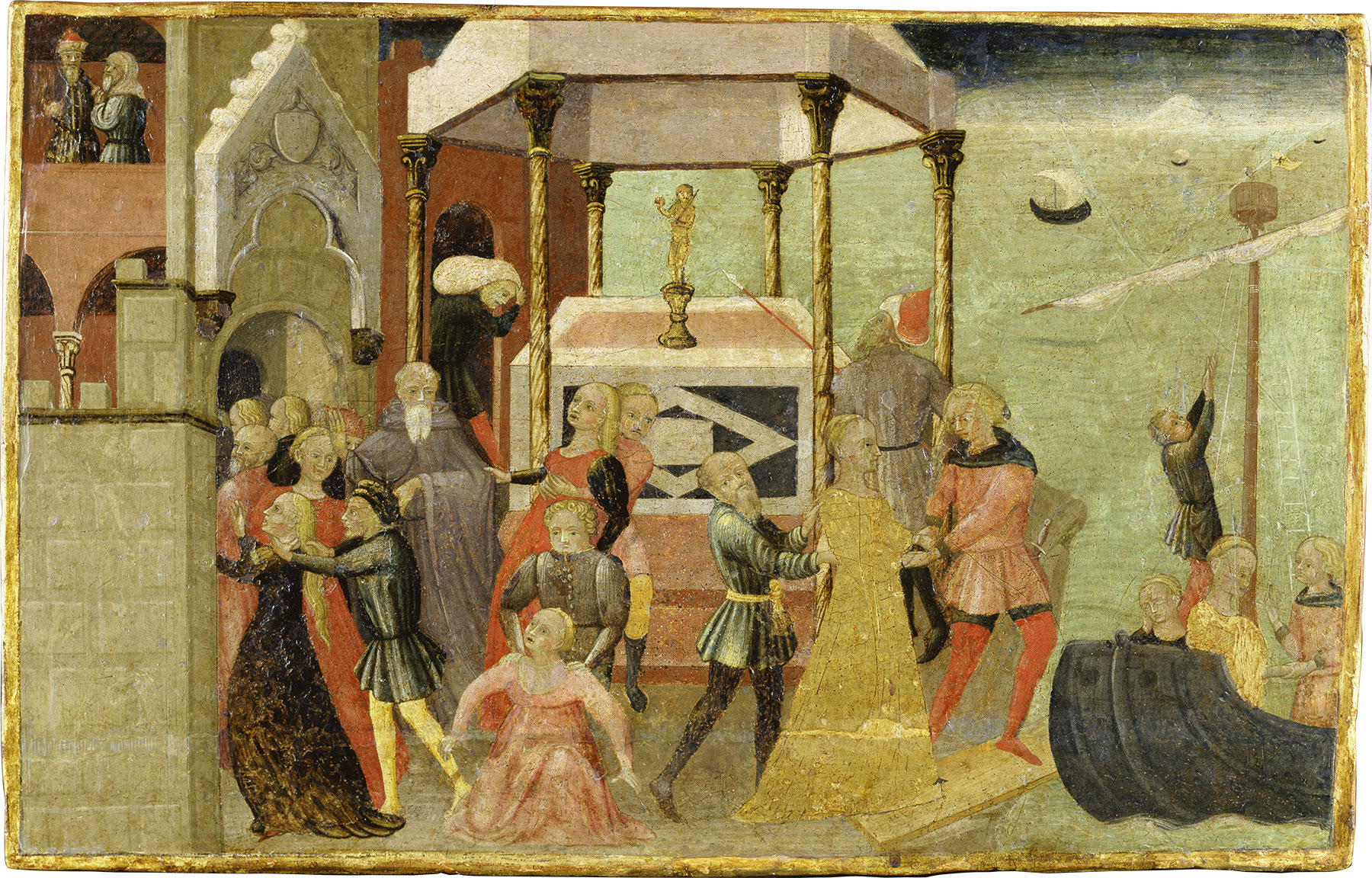

The triptych was first recorded—as formerly in the Galerie D’Atri, Paris—by Federico Zeri in his 1978 review of Piero Torriti’s catalogue of paintings in the Pinacoteca Nazionale, Siena.4 Zeri grouped it and five other works around a modest panel in the Siena Pinacoteca (fig. 1), correcting an effort that had been made forty years earlier by John Pope-Hennessy to identify one of the anonymous followers of Sassetta active in midcentury Siena.5 Zeri retained the name of convenience coined by Pope-Hennessy, “Master 185,” but rejected all but one of his attributions: a triptych formerly in the Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.,6 subsequently (1997) in a private collection in Milan,7 representing the Virgin and Child Enthroned with Saints Michael and Nicholas of Bari. To these, he added another triptych, in the Broglio collection in Paris in 1951, representing the Madonna of Humility with four prophets and Saints Jerome and Thomas Aquinas, as well as two panels also representing the Madonna of Humility that presumably once stood at the centers of similar triptychs: one formerly (1976) in the collection of Heinz Kisters at Kreuzlingen, Switzerland,8 and the other, at the time, with Luigi Grassi on the London art market. Finally, he included with these paintings, all of which are similar in size and format, two fragments of a cassone front in the Städel Museum, Frankfurt (fig. 2), representing scenes of the Abduction of Helen of Troy.9 Although Rudolf Hiller von Gaertringen claimed that the Frankfurt panels are extraneous to the group, his argument is based on an unpersuasive dating of the panels three decades too early, invoking comparisons to Florentine cassoni that bear no relation to the development of the genre in Siena.10 Another cassone front, representing the story of Lucretia, once attributed by Bernard Berenson to Guidoccio Cozzarelli, was correctly recognized by Everett Fahy as a final addition to the corpus of work by Master 185.11

All the paintings by Master 185 so far identified are modest in scale and were intended for a domestic market; a suggestion to recognize his hand among the frescoes of secular scenes at the Eremo di Lecceto is unconvincing.12 The devotional panels—all triptychs or fragments of triptychs—are uniformly refined in their carpentry, their gilding, and their decorative elements, and uniformly unassuming in artistic quality. Their style is entirely dependent on the example of Sassetta, and it is not unreasonable to suppose that the artist was an assistant or technician in the latter’s workshop. It remains to be determined whether these works represent only the stage in the painter’s career that followed Sassetta’s death in 1450, whether any of them might have been among the lavorii rimasti (unfinished works) noted in Sassetta’s estate inventory13—and whether other, more ambitious works loosely related to these in style might also be attributable to Master 185 working in Sassetta’s studio, over Sassetta’s designs and under his guidance. Two candidates in the last category might be the triptychs in the museums in Pienza and in El Paso, Texas (fig. 3)—frequently but mistakenly attributed to the Osservanza Master—that were associated by Berenson with the Frankfurt cassone fragments. In the case of the Yale triptych, there is an exaggerated difference in quality between the wooden poses and stiff draperies of all the painted figures and the calligraphic elegance of the engraved lines defining the flowing draperies of the angels holding a crown above the Virgin’s head, sufficient to raise the possibility that the latter might be traced from a drawing by Sassetta or even possibly represent the rudiments of his initial work on the panel. The only punch tool used in this work that can be identified among the impressions catalogued by Mojmír Frinta appears to have belonged to Sassetta.14 The presence of Saint Bernardino in the right wing of the triptych should argue for a date after that saint’s canonization in 1450, but there is some evidence that images of Bernardino as a saint circulated freely in Siena from the time of his death in 1444. —LK

Published References

Zeri, Federico. Review of La Pinacoteca Nazionale di Siena: I dipinti dal XII al XV secolo, by Piero Torriti. Antologia di belle arti 2 (1978): 149–52., 151, no. 6; Torriti, Piero. La Pinacoteca Nazionale di Siena: I dipinti. 2nd ed. Genoa: Sagep, 1990., 177

Notes

-

According to an annotation on the reverse of a photograph of the painting in the Fototeca Zeri, Federico Zeri Foundation, Bologna, inv. no. 15074. ↩︎

-

According to a photocopy of a check stub made out to Richard Mills, September 20, 1967; curatorial files, Department of European Art, Yale University Art Gallery. ↩︎

-

Christiansen, Keith. “Three Dates for Sassetta.” Gazette des beaux-arts 114 (1989): 264–68., 264–68. ↩︎

-

Zeri, Federico. Review of La Pinacoteca Nazionale di Siena: I dipinti dal XII al XV secolo, by Piero Torriti. Antologia di belle arti 2 (1978): 149–52., 151, no. 6. ↩︎

-

Pope-Hennessy, John. Sassetta. London: Chatto and Windus, 1939., 177–78. ↩︎

-

Inv. no. 29.6.150. ↩︎

-

According to a note in the Fototeca Zeri, Federico Zeri Foundation, Bologna, inv. no. 15070. ↩︎

-

Sale, Christie’s, London, December 9, 1988, lot 5. ↩︎

-

The other cassone front in Frankfurt is inv. no. 1004. ↩︎

-

von Gaertringen, Rudolf Hiller. Italienische Gemälde im Stadel, 1300–1550: Toskana und Umbrien. Mainz, Germany: Philipp von Zabern, 2004., 235–43. ↩︎

-

For the object, see sale, Sotheby’s, New York, January 24, 2008, lot 38; and Berenson, Bernard. “Guidoccio Cozzarelli and Matteo di Giovanni.” In Essays in the Study of Sienese Painting, 81–94. New York: F. F. Sherman, 1918., 93–94, fig. 60. ↩︎

-

Merlini, Maria. “Pittura tardogotica a Siena: Pietro di Ruffolo, il ‘Maestro di Sant’Ansano’ e il cantiere di Lecceto.” Prospettiva 95–96 (1999): 92–110., 110n48. ↩︎

-

See Pietrasanta, Alexandra. “A ‘lavorii rimasti’ by Stefano di Giovanni, called Sassetta.” Connoisseur 712 (1971): 95–99., 95–99. ↩︎

-

Frinta, Mojmír S. Punched Decoration on Late Medieval Panel and Miniature Painting. Vol. 1, Catalogue Raisonné of All Punch Shapes. Prague: Maxdorf, 1998., 259, no. Gb9. ↩︎