James Jackson Jarves (1818–1888), Florence, by 1859

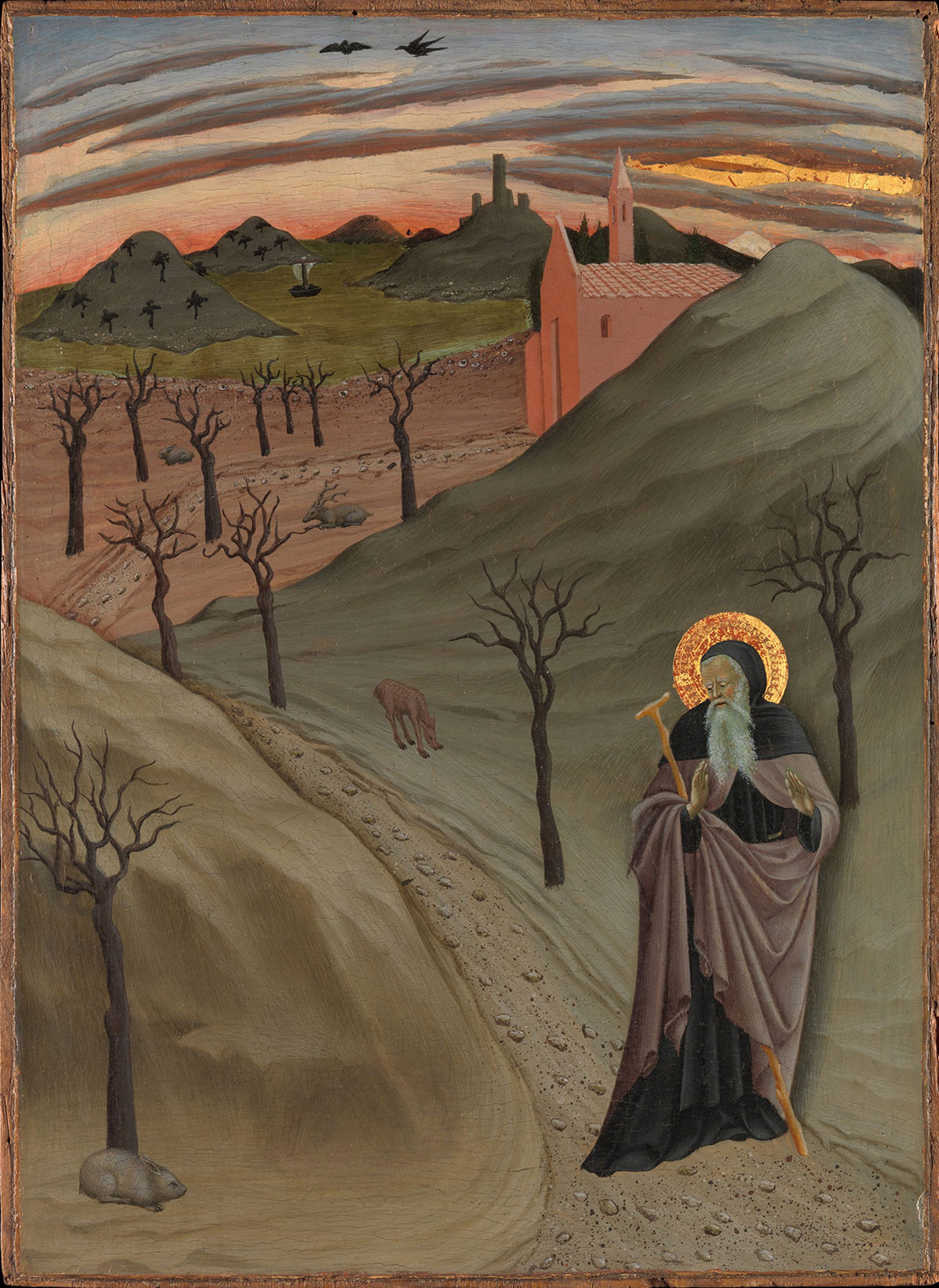

The panel support, of a vertical wood grain, has been thinned to a depth of 1.5 centimeters, waxed, and cradled. A partial split, 15 centimeters from the right edge, has resulted in a large total loss to the paint surface, approximately 16.5 centimeters long and 2.5 centimeters wide, rising from the bottom edge through Saint Anthony’s feet (which are a modern invention) to just below the wing of the demon standing above him. Another split, 22 centimeters from the right edge, has resulted in no deformation of the paint surface, while two minor splits, visible through the paint layers 9 centimeters and 3.5 to 4.5 centimeters from the left edge—the first passing through Saint Anthony’s head and the second reaching from the hands of the leftmost demon to the top of the panel—are not visible on the reverse. The left, bottom, and right margins of the picture field retain a barb of gesso and paint, and a small section of barb is also visible at the left of the top edge. The gilding and paint surfaces are beautifully preserved, although lightly abraded from a vigorous cleaning in 1950–52. The gold belly and face of the demon to the right of Saint Anthony have been scraped away. They were repainted by Elisabeth Mention in a treatment of 1998, as were local flaking losses in the wings of the same demon, along broad lines of craquelure in the landscape above his club, and in the face and torso of the demon flying in with a snake at the right.

No question in the study of Sienese Renaissance painting is as vexed or contentious as the identity of the artist or artists who painted the series of eight scenes from the legend of Saint Anthony Abbot, of which this and the related panel in Yale’s collection (see Master of the Osservanza, Saint Anthony Abbot Tempted by the Devil in the Guise of a Woman) formed part. The eight scenes, in narrative sequence according to the version of the saint’s life popularized by the fourteenth-century Dominican Domenico Cavalca (in his Vite dei santi padre), comprise:

-

Saint Anthony Abbot Renouncing His Worldly Goods, Gemäldegalerie, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin (fig. 1);

-

Saint Anthony Abbot Distributing His Wealth to the Poor, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. (fig. 2);

-

Saint Anthony Abbot Leaving His Monastery, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. (fig. 3);

-

Saint Anthony Abbot Tempted by the Devil in the Guise of a Woman;

-

Saint Anthony Abbot Tormented by Demons (the present panel);

-

Saint Anthony Abbot Tempted by a Porringer of Gold, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (fig. 4);

-

The Meeting of Saints Abbot Anthony and Paul, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. (fig. 5);

-

The Death of Saint Anthony Abbot, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. (fig. 6).

The first two of the series to be brought to public attention were the paintings now at Yale, acquired by James Jackson Jarves sometime before 1859 and exhibited by him in New York in 1860. Jarves thought they were by two different artists and—presumably because of their different shapes and sizes—did not associate them as fragments of a single narrative cycle. Saint Anthony Abbot Tempted by the Devil in the Guise of a Woman is listed in all of Jarves’s writings and in all the catalogues of his collection as by Sassetta,1 a designation that was first called into question only in 1940. Saint Anthony Tormented by Demons is instead described as by an unknown painter of the Sienese school from the second quarter of the fifteenth century. It was first associated directly with its companion and like it was assigned to Sassetta by Bernard Berenson and F. Mason Perkins.2 Berenson initially believed that the two panels at Yale formed part of a predella with another scene of the torments of Saint Anthony by Sassetta in the Pinacoteca Nazionale, Siena,3 notwithstanding the fact that the latter is identical in subject with the Jarves Saint Anthony Tormented by Demons. Although this association was discarded by Giacomo de Nicola as early as 1913, traces of it linger in subsequent scholarship4 and in the date range of 1423–26 assigned to the Yale panels in later editions of Berenson’s lists.5 These dates properly refer to the Siena predella panel, part of the Arte della Lana altarpiece documented as Sassetta’s earliest work.

Reconstruction of the Saint Anthony series further progressed with Mary Logan Berenson’s publication of a scene of the Temptation of Saint Anthony, then in the collection of Prince Ourusoff in Vienna, now in the Robert Lehman Collection at the Metropolitan Museum of Art (see fig. 4).6 Two panels then in the collection of Dan Fellows Platt in Englewood, New Jersey, now in the Samuel H. Kress Collection at the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. (see figs. 2–3), had been known as early as 1907, when they were attributed to Sassetta by Perkins. He, however, did not correctly identify their subjects—Saint Anthony Distributing His Wealth to the Poor and Saint Anthony Leaving His Monastery—with the result that they were only recognized as parts of the Saint Anthony series in 1931, when Ellis Waterhouse linked them and a sixth panel to the three at Yale and in the Lehman Collection.7 The sixth panel found by Waterhouse, The Meeting of Saints Anthony Abbot and Paul (see fig. 5), was then in the collection of the Viscount Allendale and is now reunited with the Platt pictures at the National Gallery of Art. Waterhouse also recognized the initial scene in the narrative sequence, Saint Anthony Abbot Renouncing His Worldly Goods (see fig. 1), in Berlin, formerly thought to represent a subject from the life of Saint Francis. A final episode, The Death of Saint Anthony Abbot (see fig. 6), was identified by Federico Zeri and first published by Cesare Brandi;8 this panel, too, is now in Washington at the National Gallery of Art.

Through most of the first half of the twentieth century, the then seven known panels of the Saint Anthony series were all considered important examples of Sassetta’s narrative style of painting and, with the exception of Berenson, were dated to the 1430s. John Pope-Hennessy, in his early monograph on Sassetta, acknowledged the difficulty of reconciling them with the tendency of that artist’s intellectual and pictorial development, as charted in securely documented works on either side of the 1430s, but rather than question the attribution, he posited a self-conscious period of Gothicizing détente in Sassetta’s career around the time of the so-called Osservanza altarpiece (fig. 7), which was then believed to be dated 1436.9 Roberto Longhi responded immediately and negatively, suggesting that it was artificial and simplistic to think of the Osservanza triptych, or the related Birth of the Virgin altarpiece in Asciano (fig. 8), as evidence of a Gothic phase in Sassetta’s career.10 He proposed instead that these and several works closely related to them should be considered efforts of a different artist, “d’una cultura parallela a quella del Sassetta ma più insistentemente arcaica” (of a culture parallel to Sassetta’s but more insistently archaic). Although he did not specifically list the Saint Anthony scenes as part of this group, he concluded with an exhortation that some young scholar ought to study the scenes from the life of Saint Anthony in relation to “questo nobile spirito” (this noble spirit). One of his pupils, Alberto Graziani, took up this challenge in a lecture delivered at the Kunsthistorisches Institut in Florenz in 1942, published posthumously in 1948, in which he established a solid critical basis for construction of an independent artistic personality that he christened the “Osservanza Master,” as well as for including the Saint Anthony panels in this artist’s oeuvre.11

Initial response to Longhi’s and Graziani’s thesis was mixed. Anglo-Saxon scholars, chiefly Berenson and Pope-Hennessy, did not believe that the group of works assembled around the Osservanza triptych was strictly homogeneous, and they strove to retain some degree of Sassetta’s agency for several of them.12 Italian scholars were divided between those who accepted Longhi’s arguments in toto and those who, following a suggestion made by Cesare Brandi, believed that this group of paintings probably represented the early career of Sano di Pietro.13 Charles Seymour, Jr., added an element of technical analysis to the debate when he published macrophotographic evidence that the two Saint Anthony panels at Yale were painted by two different artists, but his conclusion that one of the two is likely to have been Sassetta diminished the impact his arguments ought to have made.14 Aside from an appreciative note by Pope-Hennessy, a confused attempt by Enzo Carli to apply the same analytical technique to other paintings in the Osservanza group, and an endorsement by Keith Christiansen, the contention that the Osservanza Master was not one but two distinct personalities has largely been downplayed or ignored.15 Miklós Boskovits rejected the hypothesis outright and decisively, writing that “proper art historical evaluation of the Saint Anthony stories must be based on recognition of the stylistic unity of the group. . . . Divergent solutions in the pictorial handling of some details result in differences more apparent than real: that is, they are the kind that one often finds when comparing individual passages of a large altarpiece or fresco cycle. Assistants might sometimes have intervened and variations might also reflect the different moods of a single artist. In the case of the Saint Anthony stories, the general uniformity of the painting style . . . and the consistently fine pictorial conduct argue in favor of execution by a single artist.”16

Boskovits’s summary assessment may be understandable if considering only the four Saint Anthony panels in Washington: variation within the figure style among these four scenes is subtle, and the architectural settings in three of them are uniformly complex and competent. This is unequivocally not the case with the two Saint Anthony panels at Yale, where it is possible, even without the aid of macrophotographs, to observe striking differences in conception and technique that are incompatible with an attribution to a single artist. In Saint Anthony Tempted by the Devil, for example, the stony path of virtue on which the saint stands establishes a sense of pictorial depth by diminishing gradually in width as it meanders back into space. In Saint Anthony Tormented by Demons, the same path effectively defeats any impression of recession into depth as it soars flatly up the picture plane. In the first panel, the path is painted with careful striations of gray and cream overlaid with individually delineated rocks and stones; in the second, it is rendered in mauve with crude, hasty slashes of gray wash, a few pointillist pebbles, and random grainy spray from the tip of the artist’s brush in the manner of fly-specking.17 In the first panel, the saint’s beard is painted with long, slender, individual strokes of white paint, indicating each separate hair; his fingers are fine and nervous, his nose is thin. In the second, the beard is indicated with a shorthand notation of daubed curls, the nose is bulbous, and the fingers and hands are inflated. The trees in the first panel are of two types, intended to differentiate their relative position in space: Those in the foreground are rendered as reserves of black with individually drawn yellow and green leaves; those in the distance are instead shown as dense clusters with an overall stipple pattern of light and dark. In the second panel, all the trees, regardless of their notional distance from the viewer, are thick, dense forms of green and black, more emblematic than naturalistic in shape. Saint Anthony’s hermitage in the Temptation is a solidly foreshortened cube, with carefully rendered (and carefully foreshortened) terracotta roof tiles. In the Torment, the monastic building is a facade with no structural integrity whatsoever. It is not possible to maintain that differences such as these can be encompassed within the potential of a single artistic mind and hand. They are an indication of two separate artistic intelligences, trained in separate manual traditions and championing distinctive pictorial ambitions.

Granted the need to understand the oeuvre of the so-called Osservanza Master as embodying the work of more than one artist, it is nevertheless true that the majority of paintings ascribed to this hand are, in fact, by one of them only, not by both. It is also evident that the artist responsible for this majority of the works in question should be identified with the young Sano di Pietro. The lingering difficulty, even for those scholars who recognize the hybrid nature of this body of work, is accepting the corollary fact that it would be Sano, not his still anonymous “partner,” who should be considered the head of their joint enterprise. Modern scholarship tends to underestimate the intellectual and artistic value of Sano’s long and exceedingly productive career, while at the same time it prizes the values of rational pictorial logic implied in such a painting as the Saint Anthony Tempted by the Devil. It is anachronistic, however, to insist that the apparently more cerebral of the two painters must, ipso facto, have been head of the shared studio and chiefly responsible for designing the commissions that issued from it. It is all but certain, for example, that the master of the Temptation designed and painted the architectural backdrops in the Berlin Saint Anthony Renouncing His Worldly Goods (see fig. 1) and in three of the panels in Washington, Saint Anthony Distributing His Wealth to the Poor (see fig. 2), Saint Anthony Leaving His Monastery (see fig. 3), and the Death of Saint Anthony (see fig. 6).18 It does not necessarily follow that he was in charge of the full scope of the commission. Only a single panel of the Saint Anthony series can be attributed to him exclusively, whereas Sano can be shown to have painted three scenes on his own—Saint Anthony Tempted by a Porringer of Gold (see fig. 4); Saint Anthony Tormented by Demons (the present panel at Yale); The Meeting of Saints Anthony and Paul (see fig. 5)—and to have collaborated on four of the others. Other key works, such as the Volkhamer Lamentation over the Dead Christ in the collection of the Monte dei Paschi di Siena, datable to 1432–33, or the Passion Polyptych recently reconstructed by Andrea De Marchi and dated by him ca. 1440,19 can be attributed in their entirety to Sano di Pietro, as can a major portion of the Osservanza triptych (only the left lateral panel is not fully by Sano di Pietro) (see fig. 7) and many of the figures in the Asciano Birth of the Virgin (see fig. 8).20 In this respect, the “Osservanza Master,” as he was described by Longhi in 1940 and by Graziani in 1948, effectively is Sano di Pietro. The proper art-historical debate should not be quibbling, sometimes with embarrassing incivility,21 over this question but rather inquiring whether that original reconstruction of an “Osservanza Master” as a distinct artistic personality was accurate.

The Osservanza Master was born as an art-historical concept in an effort to free Sassetta from the baggage of miscellaneous attributions that diminished his revolutionary stature in the early progress of the developing Renaissance style in Italian painting in the second quarter of the fifteenth century. The argument was intended from the outset to be polemical and polarizing, in the sense of categorizing works of art as either progressive or archaizing, Renaissance or counter-Renaissance. It has evolved into a far more nuanced, and historically plausible, reconsideration of the context of Sassetta’s work in Siena and a reappraisal of Sano di Pietro’s stature and his emergence as a major artist a decade and a half earlier than had previously been understood. It leaves a minor painter—minor in terms of the volume of his output, not of his talent—in search of an effective name, as the eponymous work by which he was formerly known is predominantly by another artist. Elucidating the exact contours of his activity is unlikely ever to achieve scholarly consensus, as so large a percentage of his paintings were collaborative. Proposing to identify him with the historical personality of Vico di Luca (documented 1426–42), a possibility first raised by Graziani, or another artist documented as a collaborator of Sano, Lionardo di Nanni (documented 1428–65), recently identified by Alessandro Bagnoli,22 must ultimately be acknowledged to be purely speculative. It does seem reasonable to conclude that whoever he was, he did not outlive Sassetta: no paintings plausibly datable past midcentury show any evidence of intervention by him, in any aspect of their creation.23

Far less controversial than the identity of the artist once known as the Osservanza Master, but no more susceptible of resolution, have been discussions of the reconstruction and original provenance of the structure from which the eight scenes from the legend of Saint Anthony derive. Waterhouse, who knew seven of the eight scenes, recognized that the punch tooling visible only along the top margins of two of them implied that they were originally oriented one above the other, rather than horizontally as in a conventional narrative predella, and that they probably flanked a full-length carved or painted image of Saint Anthony, a proposal later confirmed by observation of the vertical wood grain of their supports.24 He suggested that the first three scenes in narrative sequence (see figs. 1–3), which all show the saint in his youth, would have stood to the left of this central image, while the three scenes in which he appears as an elderly, white-bearded monk (the present panel and figs. 4–5) would have stood to the right. He felt it probable that Saint Anthony Leaving His Monastery (see fig. 3) and The Meeting of Saints Anthony and Paul (see fig. 5) were placed at the top of their respective columns, as they both have gilded and punched “skies” along their upper margins. He questioned whether the Saint Anthony Tempted by the Devil at Yale, which differs in size and shape from the others, might have come from a different structure but concluded that “it is better, for the present, to assume that it belongs to this series as the subject must certainly have been included,” placing it in a hypothetical predella beneath the structure, from which two other scenes must be missing. Graziani reversed the sequence, supposing that the narrative proceeded from top to bottom on either side of an image of the seated Saint Anthony, placing the Berlin Saint Anthony Renouncing His Worldly Goods (see fig. 1) and the present panel at the top and the Washington Saint Anthony Leaving His Monastery and The Meeting of Saints Anthony and Paul at the bottom, with the Yale Saint Anthony Tempted by the Devil and two missing narrative scenes in a predella beneath.25 Pope-Hennessy returned to Waterhouse’s original proposal but shifted the Saint Anthony Tempted by the Devil and the Washington Death of Saint Anthony Abbot (see fig. 6), the latter of which had been unknown to Waterhouse, to the top rather than bottom of the columns, to preserve narrative sequence.26 Christiansen also believed the narrative progressed from bottom to top, but he returned the two horizontal panels to a separate predella beneath the structure, out of strict sequence.27 Boskovits argued that Graziani’s arrangement must have been correct based on the example of earlier vita icons, all of which read from top to bottom with no scenes out of narrative sequence, as would have been the case in Waterhouse’s or Christiansen’s reconstruction.28 This view is accepted by De Marchi in the most recent contribution to the debate.29 It is, however, only possible to accept this reconstruction if the sequence of the present panel and Saint Anthony Tempted by a Porringer of Gold (see fig. 4) is reversed. Christiansen published physical evidence, in the form of continuous damage from a knot in their panel supports, that the former stood immediately beneath the latter.30

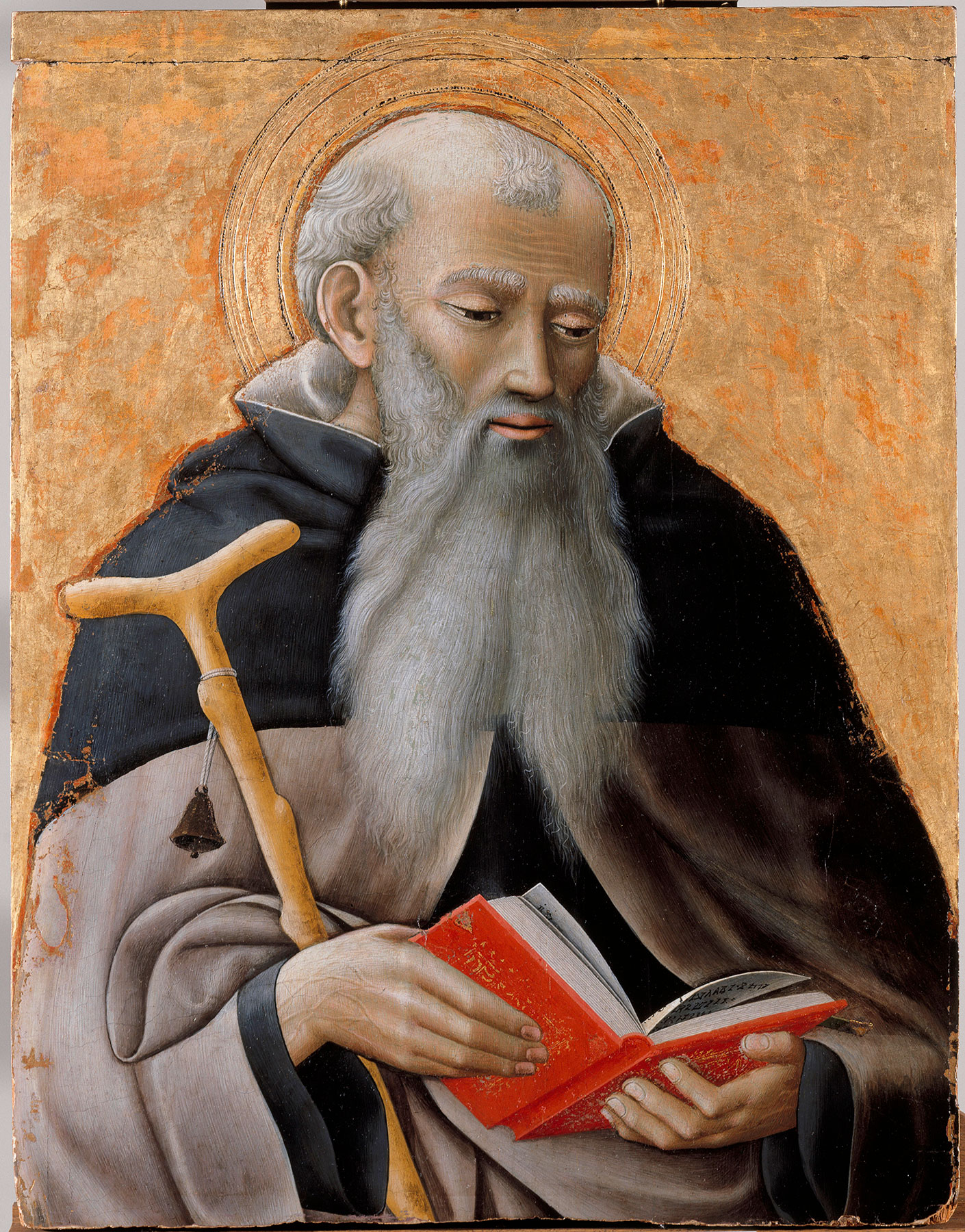

Proposals to identify the missing central panel of the structure have revolved around two principal candidates. Graziani first suggested that a half-length Saint Anthony Abbot portrayed reading, in the Musée du Louvre, Paris (fig. 9), painted by the Osservanza Master and closely related in style to the Saint Anthony panels, might be a fragment of the center panel of that altarpiece.31 He assumed that the Louvre panel, whose background gilding is modern, had been cropped on all four sides and that originally it portrayed the saint seated. This proposal was rejected by Pope-Hennessy, Christiansen, and Boskovits, largely due to the saint’s being shown not in the conventionally hieratic frontal pose of the main figure in a vita icon but rather turned in three-quarter profile, a pose typically encountered in lateral panels of a polyptych.32 Pope-Hennessy initially suggested that a full-length Saint Anthony Abbot by Sassetta in the collection of the Monte dei Paschi di Siena (see Stefano di Giovanni, called Sassetta, Virgin Annunciate, fig. 4) might be the missing center panel to this complex, while arguing for Sassetta’s partial responsibility for the Saint Anthony scenes.33 He later withdrew this suggestion, recognizing both that Sassetta was not personally involved in this commission and that the Monte dei Paschi Saint Anthony was probably a lateral panel from another altarpiece, in which it would have been accompanied by the full-length Saint Nicholas of Bari, then recently acquired by the Musée du Louvre (see Stefano di Giovanni, called Sassetta, Virgin Annunciate, fig. 5).34 De Marchi returned to Graziani’s thesis, citing the evidence of X-radiography of the Louvre Saint Anthony, made available to him by Elisabeth Ravaud of the Centre de Recherche et de Restauration des Musées de France.35 According to De Marchi, the Louvre panel shows evidence of dowel holes on its sides that connected it to adjacent panels at both right and left, as well as three nail holes aligned horizontally along the length of panel just above the level of the saint’s hands. The latter would have secured a batten across the back of the panel, which, given its position, must have been the middle of three battens running across the bottom, center, and top of the complete structure. The placement of these battens implies that the Louvre panel did originally show the saint seated, not standing, but the presence of dowel pegs is difficult to reconcile with the continuous painted surface of a vita icon. None of the Saint Anthony panels shows evidence of dowel pegs on the sides, and X-rays of the present panel show no evidence of nails securing a batten. As this panel occupied either the center or the bottom of the right side of the structure, at least one of the battens should have passed across it.36

A final question concerning the Saint Anthony panels that has preoccupied scholarship is their possible original provenance. This was not questioned as having been Sienese until Piero Scapecchi noted that the two panels formerly in the Platt collection and now in Washington, D.C. (see figs. 2–3) are recorded in the nineteenth century in the Caccialupi collection in Macerata, in the Marches.37 Scapecchi also postulated that Jarves may have acquired the two panels now at Yale from the same source, during his visit to Macerata in the 1850s, although such a possibility is nowhere documented in any of Jarves’s own catalogues. As Scapecchi was also able to identify the shield of arms appearing in the vaulting of the doorway behind Saint Anthony in the Washington Saint Anthony Distributing His Wealth to the Poor (see fig. 2) as those of the Martinozzi family of Siena, a branch of which was established at San Severino Marche, not far from Macerata, he concluded that the original commission must have been Marchigian, not Sienese. Though reiterated by Cecilia Alessi and Scapecchi, only Boskovits has defended this theory with any conviction.38 Linda Pisani reported that the arms of the Martinozzi of San Severino were different from those of the Martinozzi of Siena,39 and it is the Sienese arms that appear in Saint Anthony Distributing His Wealth to the Poor. The Martinozzi owned patronage rights to altars in San Francesco and Sant’Agostino in Siena, the latter dedicated to Saint Anthony Abbot.40 Christiansen noted that the pastoral visit of Monsignor Francesco Bossi to this altar in 1575 describes its decoration in vague terms that imply a conventional polyptych rather than a vita icon: “Icona vero erat cum imagine sancti Antonii in tabula et aliis figuris sanctorum auro ornatis” (A true image of Saint Anthony on panel with other figures of saints, ornamented in gold).41 In support of a possible provenance from this altar, despite this negative evidence, De Marchi observed that in the three scenes in New York and New Haven showing temptations of Saint Anthony, the saint wears the belt of the Augustinian hermits over his black habit and beneath his scapular.42 If De Marchi’s proposal to identify the fragmentary Saint Anthony Abbot in the Louvre as the central panel of this complex is correct, it is worth considering the possibility that the complete structure was not of the class of a vita icon but may instead have resembled a structure similar to Giovanni di Paolo’s later Pizzicaiuoli altarpiece (1449/61), in which a conventional altarpiece was surrounded by narrative scenes from the life of a saint. Though unusual, possibly unique, such a construction could explain some of the contradictory physical evidence presented by the panels themselves. —LK

Published References

Jarves, James Jackson. Descriptive Catalogue of “Old Masters” Collected by James J. Jarves to Illustrate the History of Painting from A.D. 1200 to the Best Periods of Italian Art. Cambridge, Mass.: H. O. Houghton, 1860., 48, nos. 46–47; Jarves, James Jackson. Art Studies: The “Old Masters” of Italy; Painting. New York: Derby and Jackson, 1861., 239–40; Sturgis, Russell, Jr. Manual of the Jarves Collection of Early Italian Pictures. New Haven: Yale College, 1868., 53, 55, nos. 48, 53; W. F. Brown, Boston. Catalogue of the Jarves Collection of Early Italian Pictures. Sale cat. November 9, 1871., 19, nos. 48, 53; Rankin, William. “Some Early Italian Pictures in the Jarves Collection of the Yale School of Fine Arts at New Haven.” American Journal of Archaeology 10, no. 2 (April–June 1895): 137–51., 143; Berenson, Bernhard [sic]. “A Sienese Painter of the Franciscan Legend: Part II—(Conclusion).” Burlington Magazine 3 (1903): 171–84., 180–81; Crowe, Joseph Archer, and Giovanni Battista Cavalcaselle. A History of Painting in Italy, Umbria, Florence and Siena from the Second to the Sixteenth Century. Vols. 1–4, ed. Robert Langton Douglas. Vols. 5–6, ed. Tancred Borenius. London: J. Murray, 1903–14., 5:170; Perkins, F. Mason. “Pitture senesi negli Stati Uniti.” Rassegna d’arte senese 1 (1905): 74–78., 76; Rankin, William. Notes on the Collections of Old Masters at Yale University, the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, the Fogg Museum of Harvard University. Wellesley, Mass.: Department of Art, Wellesley College, 1905., 10, nos. 48, 53; Berenson, Bernard. The Central Italian Painters of the Renaissance. 2nd rev. ed. New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1909., 246; Logan Berenson, Mary. “Il Sassetta e la leggenda di S. Antonio Abate.” Rassegna d’arte 11, no. 12 (December 1911): 202–3., 202–3; De Nicola, Giacomo. “Sassetta between 1423 and 1433—I.” Burlington Magazine 23, no. 124 (July 1913): 207–9, 212–15., 213–14; Sirén, Osvald. A Descriptive Catalogue of the Pictures in the Jarves Collection Belonging to Yale University. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1916., 151–54, nos. 57–58; Perkins, F. Mason. “Some Sienese Paintings in American Collections: Part Three.” Art in America 9, no. 1 (1920): 6–21., 13–14; Dami, Luigi. “Giovanni di Paolo miniatore e i paesisti senesi.” Dedalo 4 (1923–24): 268–303., 283, 292–93; van Marle, Raimond. The Development of the Italian Schools of Painting. Vol. 9. The Hague: M. Nijhoff, 1927., 318–20; Offner, Richard. Italian Primitives at Yale University: Comments and Revisions. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1927., 7, 39–40, figs. 30–31; “Handbook: A Description of the Gallery of Fine Arts and the Collections,” special issue, Bulletin of the Associates in Fine Arts at Yale University 5, nos. 1–3 (1931): 1–64., 26; Venturi, Lionello. Pitture italiane in America. 2 vols. Milan: Ulrico Hoepli, 1931., pls. 122–24; Waterhouse, Ellis K. “Sassetta and the Legend of St. Antony Abbot.” Burlington Magazine 59 (1931): 108–9, 112–3., 108, 112–13; Berenson, Bernard. Italian Pictures of the Renaissance: A List of the Principal Artists and Their Works with an Index of Places. Oxford: Clarendon, 1932., 512; Edgell, George Harold. A History of Sienese Painting. New York: Dial, 1932., 192, 194; Venturi, Lionello. Italian Paintings in America. Trans. Countess Vanden Heuvel and Charles Marriott. 3 vols. New York: E. Weyhe, 1933., 3: pls. 140–41, under pl. 138; Berenson, Bernard. Pitture italiane del Rinascimento: Catalogo dei principali artisti e delle loro opera. Trans. Emilio Cecchi. Milan: Ulrico Hoepli, 1936., 441; Pope-Hennessy, John. Sassetta. London: Chatto and Windus, 1939., 70–77, 82–83, 85–86, 92nn39 and 43, 115, pl. 12; Longhi, Roberto. “Fatti di Masolino e di Masaccio.” Critica d’arte 5 (July–December 1940): 145–91., 188–89; Berenson, Bernard. Sassetta: Un pittore senese della leggenda francescana. Florence: Electa, 1946., 52; Carli, Enzo. Capolavori dell’arte senese. Florence: Electa, 1946., 45; Comstock, Helen. “The Yale Collection of Italian Paintings.” Connoisseur 118 (September 1946): 45–52., 50, no. 7; Graziani, Alberto. “Il Maestro dell’Osservanza.” Proporzioni 2 (1948): 76–88., 76, 83–84; Brandi, Cesare. Quattrocentisti senesi. Milan: Ulrico Hoepli, 1949., 79, 83, 255–56, 284, no. 98; Kaftal, George. Iconography of the Saints in Tuscan Painting. Florence: Sansoni, 1952., cols. 68–70, no. 24; Rediscovered Italian Paintings. Exh. cat. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1952., 24–27; Seymour, Charles, Jr., “The Jarves ‘Sassettas’ and the St. Anthony Altarpiece.” Journal of the Walters Art Gallery 15–16 (1952–53): 30–45, 97., 32–45, 97, figs. 1, 3, 5–6, 8, 10, 12a; Pope-Hennessy, John. “Rethinking Sassetta.” Burlington Magazine 98, no. 643 (October 1956): 364–70., 364–66, 369, figs. 28–29; Carli, Enzo. Sassetta e il Maestro dell’Osservanza. Milan: Aldo Martello, 1957., 104–21, pls. 124, 127, 129, 131; Shapley, Fern Rusk. Paintings from the Samuel H. Kress Collection: Italian Schools, XIII–XV Century. London: Phaidon, 1966., 142; Berenson, Bernard. Italian Pictures of the Renaissance, A List of the Principal Artists and Their Works with an Index of Places: Central Italian and North Italian Schools. 3 vols. London: Phaidon, 1968., 1:253; Seymour, Charles, Jr. Early Italian Paintings in the Yale University Art Gallery. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1970., 208–12, nos. 157–58; Fredericksen, Burton B., and Federico Zeri. Census of Pre-Nineteenth-Century Italian Paintings in North American Public Collections. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1972., 132, 599; Ritchie, Andrew Carnduff, and Katharine B. Neilson. Selected Paintings and Sculpture from the Yale University Art Gallery. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1972., no. 10, pl. 2; Ellen Frank, in Seymour, Charles, Jr., et al. Italian Primitives: The Case History of a Collection and Its Conservation. Exh. cat. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1972., 22–23; Fahy, Everett. Review of Paintings from the Samuel H. Kress Collection: Italian Schools XII–XV Century, by Fern Rusk Shapley; Paintings from the Samuel H. Kress Collection: Italian Schools XV–XVI Century, by Fern Rusk Shapley; Early Italian Paintings in the Yale University Art Gallery, by Charles Seymour, Jr.; and Italian Primitives: The Case History of a Collection and Its Conservation, by Charles Seymour, Jr. Art Bulletin 56, no. 2 (June 1974): 283–85., 283; Shapley, Fern Rusk. Catalogue of the Italian Paintings: National Gallery of Art. 2 vols. Washington, D.C.: National Gallery of Art, 1979., 1:320–21, 322nn2–3, 323n7; Scapecchi, Piero. “Quattrocentisti senesi nelle March: Il politico di Sant’ Antonio abate del Maestro dell’Osservanza.” Arte cristiana 71, no. 698 (1983): 287–90., 287–90; Dianne Phillips, in Shestack, Alan, ed. Yale University Art Gallery: Selections. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1983., 26; Alessi, Cecilia, and Piero Scapecchi. “Il ‘Maestro dell’Osservanza’: Sano di Pietro o Francesco di Bartolomeo?” Prospettiva 42 (1985): 13–37., 13–37; De Marchi, Andrea. Review of Die Kirchen von Siena, vol. 1.1–3, Abbadia all’Arco-S. Biagio, by Peter Anselm Riedl and Max Seidel. Prospettiva 49 (1987): 92–96., 95; John Pope-Hennessy, in Pope-Hennessy, John, and Laurence Kanter. The Robert Lehman Collection. Vol. 1, Italian Paintings. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1987., 105–9; Keith Christiansen, in Christiansen, Keith, Laurence Kanter, and Carl Brandon Strehlke. Painting in Renaissance Siena, 1420–1500. Exh. cat. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1988., 104–23, no. 10d; Christiansen, Keith. “Notes on Painting in Renaissance Siena.” Burlington Magazine 132, no. 1044 (March 1990): 205–13., 207–8; Pope-Hennessy, John. Learning to Look. New York: Doubleday, 1991., 256–57; Kenney, Elise K., ed. Handbook of the Collections: Yale University Art Gallery. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1992., 137; Garland, Patricia Sherwin, and Elisabeth Mention. “Loss and Restoration: Yale’s Early Italian Paintings Reconsidered.” Yale University Art Gallery Bulletin (1999): 32–43., 38–40; Dean, Clay. A Selection of Early Italian Paintings from the Yale University Art Gallery. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 2001., 13, 30–31, no. 8, fig. 3; Miklós Boskovits, in Boskovits, Miklós, and David Alan Brown. Italian Paintings of the Fifteenth Century: The Collections of the National Gallery of Art, Systematic Catalogue. Washington, D.C.: National Gallery of Art, 2003., 487–89, 492nn16, 22, and 27, 493nn33, 37, and 40, fig. Ig; Falcone, Maria. “La giovinezza dorata di Sano di Pietro: Un nuovo documento per la Natività della Vergine di Asciano.” Prospettiva 138 (2010): 28–34., 30; Andrea De Marchi, in Seidel, Max, et al., eds. Le arti a Siena nel primo Rinascimento: Da Jacopo della Quercia a Donatello. Exh. cat. Milan: Federico Motta, 2010., 267–71, 274; De Marchi, Andrea. “Sano di Pietro prima della Pala dei Gesuati e il ‘Maestro dell’Osservanza’: Aporie di una doppia identità.” In Sano di Pietro: Qualità, devozione e pratica nella pittura senese del quattrocento, ed. Gabriele Fattorini, 53–85. Cinisello Balsamo, Milan: Silvana, 2012., 63–65, fig. 7; Laclotte, Michel. “Quelques remarques sur le ‘cas’ Sano di Pietro.” In Sano di Pietro: Qualità, devozione e pratica nella pittura senese del quattrocento, ed. Gabriele Fattorini, 87–93. Cinisello Balsamo, Milan: Silvana, 2012., 90

Notes

-

Jarves, James Jackson. Descriptive Catalogue of “Old Masters” Collected by James J. Jarves to Illustrate the History of Painting from A.D. 1200 to the Best Periods of Italian Art. Cambridge, Mass.: H. O. Houghton, 1860., 48, nos. 46–47; Jarves, James Jackson. Art Studies: The “Old Masters” of Italy; Painting. New York: Derby and Jackson, 1861., 239–40; Sturgis, Russell, Jr. Manual of the Jarves Collection of Early Italian Pictures. New Haven: Yale College, 1868., 53, nos. 48, 53; and W. F. Brown, Boston. Catalogue of the Jarves Collection of Early Italian Pictures. Sale cat. November 9, 1871., 19, nos. 48, 53. ↩︎

-

Berenson, Bernhard [sic]. “A Sienese Painter of the Franciscan Legend: Part II—(Conclusion).” Burlington Magazine 3 (1903): 171–84., 180–81; and Perkins, F. Mason. “Pitture senesi negli Stati Uniti.” Rassegna d’arte senese 1 (1905): 74–78., 76. ↩︎

-

Inv. no. 166. ↩︎

-

De Nicola, Giacomo. “Sassetta between 1423 and 1433—I.” Burlington Magazine 23, no. 124 (July 1913): 207–9, 212–15., 213–14; and see, for example, Crowe, Joseph Archer, and Giovanni Battista Cavalcaselle. A History of Painting in Italy, Umbria, Florence and Siena from the Second to the Sixteenth Century. Vols. 1–4, ed. Robert Langton Douglas. Vols. 5–6, ed. Tancred Borenius. London: J. Murray, 1903–14., 5:169–70n1. ↩︎

-

Berenson, Bernard. Italian Pictures of the Renaissance: A List of the Principal Artists and Their Works with an Index of Places. Oxford: Clarendon, 1932., 512; and Berenson, Bernard. Pitture italiane del Rinascimento: Catalogo dei principali artisti e delle loro opera. Trans. Emilio Cecchi. Milan: Ulrico Hoepli, 1936., 441. ↩︎

-

Logan Berenson, Mary. “Il Sassetta e la leggenda di S. Antonio Abate.” Rassegna d’arte 11, no. 12 (December 1911): 202–3., 202–3. ↩︎

-

Waterhouse, Ellis K. “Sassetta and the Legend of St. Antony Abbot.” Burlington Magazine 59 (1931): 108–9, 112–3., 108, 112–13. ↩︎

-

Brandi, Cesare. Quattrocentisti senesi. Milan: Ulrico Hoepli, 1949., 199n60. ↩︎

-

Pope-Hennessy, John. Sassetta. London: Chatto and Windus, 1939., 77. ↩︎

-

Longhi, Roberto. “Fatti di Masolino e di Masaccio.” Critica d’arte 5 (July–December 1940): 145–91., 188–89n26. ↩︎

-

Graziani, Alberto. “Il Maestro dell’Osservanza.” Proporzioni 2 (1948): 76–88., 75–87, esp. 83–84. ↩︎

-

Berenson, Bernard. Sassetta: Un pittore senese della leggenda francescana. Florence: Electa, 1946., 52; and Pope-Hennessy, John. “Rethinking Sassetta.” Burlington Magazine 98, no. 643 (October 1956): 364–70., 364–70. ↩︎

-

Brandi, Cesare. Quattrocentisti senesi. Milan: Ulrico Hoepli, 1949., 82–85. ↩︎

-

Seymour, Charles, Jr., “The Jarves ‘Sassettas’ and the St. Anthony Altarpiece.” Journal of the Walters Art Gallery 15–16 (1952–53): 30–45, 97., 37–45, figs. 6–12. ↩︎

-

Pope-Hennessy, John. “Rethinking Sassetta.” Burlington Magazine 98, no. 643 (October 1956): 364–70., 366; Carli, Enzo. Sassetta e il Maestro dell’Osservanza. Milan: Aldo Martello, 1957., 110–14; and Christiansen, Keith. “Notes on Painting in Renaissance Siena.” Burlington Magazine 132, no. 1044 (March 1990): 205–13., 207–8. ↩︎

-

Miklós Boskovits, in Boskovits, Miklós, and David Alan Brown. Italian Paintings of the Fifteenth Century: The Collections of the National Gallery of Art, Systematic Catalogue. Washington, D.C.: National Gallery of Art, 2003., 489. ↩︎

-

Keith Christiansen (in Christiansen, Keith. “Notes on Painting in Renaissance Siena.” Burlington Magazine 132, no. 1044 (March 1990): 205–13., 207–8) ascribed the lack of definition in the path in this panel to severe abrasion from its most recent cleaning. This is only partly true, accounting for the absence of detail in the upper half of the path. It does not alter the essential difference in technique of execution between this panel and its companion at Yale. ↩︎

-

The compromised state of Saint Anthony Leaving His Monastery (see fig. 3) precludes confident assessment of its figure style, specifically whether the young Saint Anthony was painted, as seems to be the case, by the second artist. The two monks standing in the doorway of the monastery are by Sano di Pietro. Sano was responsible for all the figures in Saint Anthony Distributing His Wealth to the Poor (see fig. 2), with the exception of the young saint in the foreground at the right, with his beautifully foreshortened feet and elegant twisting pose. All the figures in the Death of Saint Anthony (see fig. 6) are by Sano di Pietro. ↩︎

-

For the Volkhammer Lamentation, see Andrea De Marchi, in Seidel, Max, et al., eds. Le arti a Siena nel primo Rinascimento: Da Jacopo della Quercia a Donatello. Exh. cat. Milan: Federico Motta, 2010., 258–59, no. C.31. For the Passion Polyptych, see Andrea De Marchi, in Seidel, Max, et al., eds. Le arti a Siena nel primo Rinascimento: Da Jacopo della Quercia a Donatello. Exh. cat. Milan: Federico Motta, 2010., 272–75, no. C.35. ↩︎

-

The fireplace and burning logs in the Asciano Birth of the Virgin (see fig. 8) are a clumsy insertion into the otherwise crystalline spatial logic of the setting in this majestic painting and are undoubtedly due to Sano’s intervention. Maria Falcone (in Falcone, Maria. “La giovinezza dorata di Sano di Pietro: Un nuovo documento per la Natività della Vergine di Asciano.” Prospettiva 138 (2010): 28–34.) published documentary evidence that Sano was paid for the Asciano altarpiece in 1439. As Alessandro Bagnoli notes (in Bagnoli, Alessandro, ed. Il Sassetta e il suo tempo: Uno sguardo sull’arte senese del primo quattrocento. Exh. cat. Florence: Centro Di, 2024., 104), this does not signify that Sano painted the altarpiece, merely that he was titular head of the artistic partnership. ↩︎

-

While the tone was set by the tenor of Longhi’s remarks during war time, revealing his customary disdain for Anglo-Saxon (i.e., Allied) scholarship and his visceral contempt for Bernard Berenson, in particular, a low point was reached sixty-five years later with Luciano Bellosi’s sarcastic, ad hominem attacks in Bellosi, Luciano. “Considerazioni introduttive al problema dell’identificazione tra il ‘Maestro dell’Osservanza’ e Sano di Pietro.” In Sano di Pietro: Qualità, devozione e pratica nella pittura senese del quattrocento, 43–51. Cinisello Balsamo, Milan: Silvana, 2012., 43–52. On the other hand, it is heartening to see that the catalogue of the 2024 exhibition in Massa Marittima (Bagnoli, Alessandro, ed. Il Sassetta e il suo tempo: Uno sguardo sull’arte senese del primo quattrocento. Exh. cat. Florence: Centro Di, 2024.) is dedicated “Alla memoria di Michel Laclotte, vero amico del Sassetta e del ‘Maestro dell’Osservanza’” (To the memory of Michel Laclotte, true friend to Sassetta and the Master of the Osservanza). ↩︎

-

Bagnoli, in Bagnoli, Alessandro, ed. Il Sassetta e il suo tempo: Uno sguardo sull’arte senese del primo quattrocento. Exh. cat. Florence: Centro Di, 2024., 105, 111n21. Bagnoli does not suggest that Lionardo di Nanni was the Osservanza Master, merely that Sano had a regular business practice of collaborating with other artists. His solution to the question of identifying the Osservanza Master proceeds from an assumption that the oeuvre originally isolated under that provisional name is homogeneous and represents one of the numerous business partners now confused under the corporate name Sano di Pietro. This approach to studying Sano more closely is long overdue but does not seem to address the core problem of the Osservanza Master’s group of paintings. ↩︎

-

The attempt by Cecilia Alessi and Piero Scapecchi (in Alessi, Cecilia, and Piero Scapecchi. “Il ‘Maestro dell’Osservanza’: Sano di Pietro o Francesco di Bartolomeo?” Prospettiva 42 (1985): 13–37., 13–37) to identify the Osservanza Master with Francesco di Bartolomeo Alfei (documented 1453–94) has been rejected nearly unanimously in the subsequent literature. ↩︎

-

Waterhouse, Ellis K. “Sassetta and the Legend of St. Antony Abbot.” Burlington Magazine 59 (1931): 108–9, 112–3., 13. ↩︎

-

Graziani, Alberto. “Il Maestro dell’Osservanza.” Proporzioni 2 (1948): 76–88., fig. 96. ↩︎

-

Pope-Hennessy, in Pope-Hennessy, John, and Laurence Kanter. The Robert Lehman Collection. Vol. 1, Italian Paintings. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1987., 106. ↩︎

-

Keith Christiansen, in Christiansen, Keith, Laurence Kanter, and Carl Brandon Strehlke. Painting in Renaissance Siena, 1420–1500. Exh. cat. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1988., 104. ↩︎

-

Boskovits, in Boskovits, Miklós, and David Alan Brown. Italian Paintings of the Fifteenth Century: The Collections of the National Gallery of Art, Systematic Catalogue. Washington, D.C.: National Gallery of Art, 2003., 487, 492n27. ↩︎

-

De Marchi, Andrea. “Sano di Pietro prima della Pala dei Gesuati e il ‘Maestro dell’Osservanza’: Aporie di una doppia identità.” In Sano di Pietro: Qualità, devozione e pratica nella pittura senese del quattrocento, ed. Gabriele Fattorini, 53–85. Cinisello Balsamo, Milan: Silvana, 2012.. ↩︎

-

Christiansen, Keith. “Notes on Painting in Renaissance Siena.” Burlington Magazine 132, no. 1044 (March 1990): 205–13., 207. ↩︎

-

Graziani, Alberto. “Il Maestro dell’Osservanza.” Proporzioni 2 (1948): 76–88., 84. ↩︎

-

Pope-Hennessy, John. “Rethinking Sassetta.” Burlington Magazine 98, no. 643 (October 1956): 364–70., 369; Pope-Hennessy, in Pope-Hennessy, John, and Laurence Kanter. The Robert Lehman Collection. Vol. 1, Italian Paintings. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1987., 109; Christiansen, in Christiansen, Keith, Laurence Kanter, and Carl Brandon Strehlke. Painting in Renaissance Siena, 1420–1500. Exh. cat. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1988., 104; and Boskovits, in Boskovits, Miklós, and David Alan Brown. Italian Paintings of the Fifteenth Century: The Collections of the National Gallery of Art, Systematic Catalogue. Washington, D.C.: National Gallery of Art, 2003., 487, 492n24. ↩︎

-

Pope-Hennessy, John. “Rethinking Sassetta.” Burlington Magazine 98, no. 643 (October 1956): 364–70., 366, 369. ↩︎

-

Pope-Hennessy, in Pope-Hennessy, John, and Laurence Kanter. The Robert Lehman Collection. Vol. 1, Italian Paintings. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1987., 108–9. The Saint Anthony Abbot in the Monte dei Paschi collection was first published by Zeri, in Zeri, Federico. “Towards a Reconstruction of Sassetta’s Arte della Lana Triptych (1423–6).” Burlington Magazine 98, no. 635 (February 1956): 36–39, 41., 36–41. The Louvre Saint Nicholas was published by Claudie Ressort and associated with the Saint Anthony in Foucart, Jacques, ed. Nouvelles acquisitions du Département de peintures (1980–1982). Paris: Ministère de la culture, Editions de la Réunion des musées nationaux, 1983., 8. ↩︎

-

De Marchi, Andrea. “Sano di Pietro prima della Pala dei Gesuati e il ‘Maestro dell’Osservanza’: Aporie di una doppia identità.” In Sano di Pietro: Qualità, devozione e pratica nella pittura senese del quattrocento, ed. Gabriele Fattorini, 53–85. Cinisello Balsamo, Milan: Silvana, 2012., 68. ↩︎

-

Although no evidence of batten nails is visible in the X-radiograph of the present panel, a disturbance of the paint surface near the top edge, immediately to the right of the gabled facade of the church, could be due to the movement of a nailhead—although, if so, it is unusually small for a batten nail and difficult to explain why it is not radio-opaque. ↩︎

-

Scapecchi, Piero. “Quattrocentisti senesi nelle March: Il politico di Sant’ Antonio abate del Maestro dell’Osservanza.” Arte cristiana 71, no. 698 (1983): 287–90., 288–89, 290n20. ↩︎

-

Alessi, Cecilia, and Piero Scapecchi. “Il ‘Maestro dell’Osservanza’: Sano di Pietro o Francesco di Bartolomeo?” Prospettiva 42 (1985): 13–37., 27, 36n118; and Boskovits, in Boskovits, Miklós, and David Alan Brown. Italian Paintings of the Fifteenth Century: The Collections of the National Gallery of Art, Systematic Catalogue. Washington, D.C.: National Gallery of Art, 2003., 487. ↩︎

-

Cited in De Marchi, Andrea. “Sano di Pietro prima della Pala dei Gesuati e il ‘Maestro dell’Osservanza’: Aporie di una doppia identità.” In Sano di Pietro: Qualità, devozione e pratica nella pittura senese del quattrocento, ed. Gabriele Fattorini, 53–85. Cinisello Balsamo, Milan: Silvana, 2012., 73n40. ↩︎

-

Monika Butzek, in Riedl, Peter Anselm, and Max Seidel. Die Kirchen von Siena. Vol. 1. Munich: Bruckmann, 1985., 1.1:218n78. ↩︎

-

Christiansen, in Christiansen, Keith, Laurence Kanter, and Carl Brandon Strehlke. Painting in Renaissance Siena, 1420–1500. Exh. cat. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1988., 105; and Bossi, Francesco. Visita apostolica alla diocesi di Siena, 1575. Vol. 2, Decreta, Monasteria, Ecclesiae. Transcribed by Giuliano Catoni and Sonia Fineschi. Siena: Accademia Degli Intronati, 2019., 277. ↩︎

-

De Marchi, in Seidel, Max, et al., eds. Le arti a Siena nel primo Rinascimento: Da Jacopo della Quercia a Donatello. Exh. cat. Milan: Federico Motta, 2010., 267. ↩︎