Robert Langton Douglas (1864–1951), London; Dan Fellows Platt (1873–1937), Englewood, N.J., by 1911–36; E. and A. Silberman Galleries, N.Y.; Hannah D. and Louis M. Rabinowitz (1887–1957), Sands Point, Long Island, N.Y., by 1944

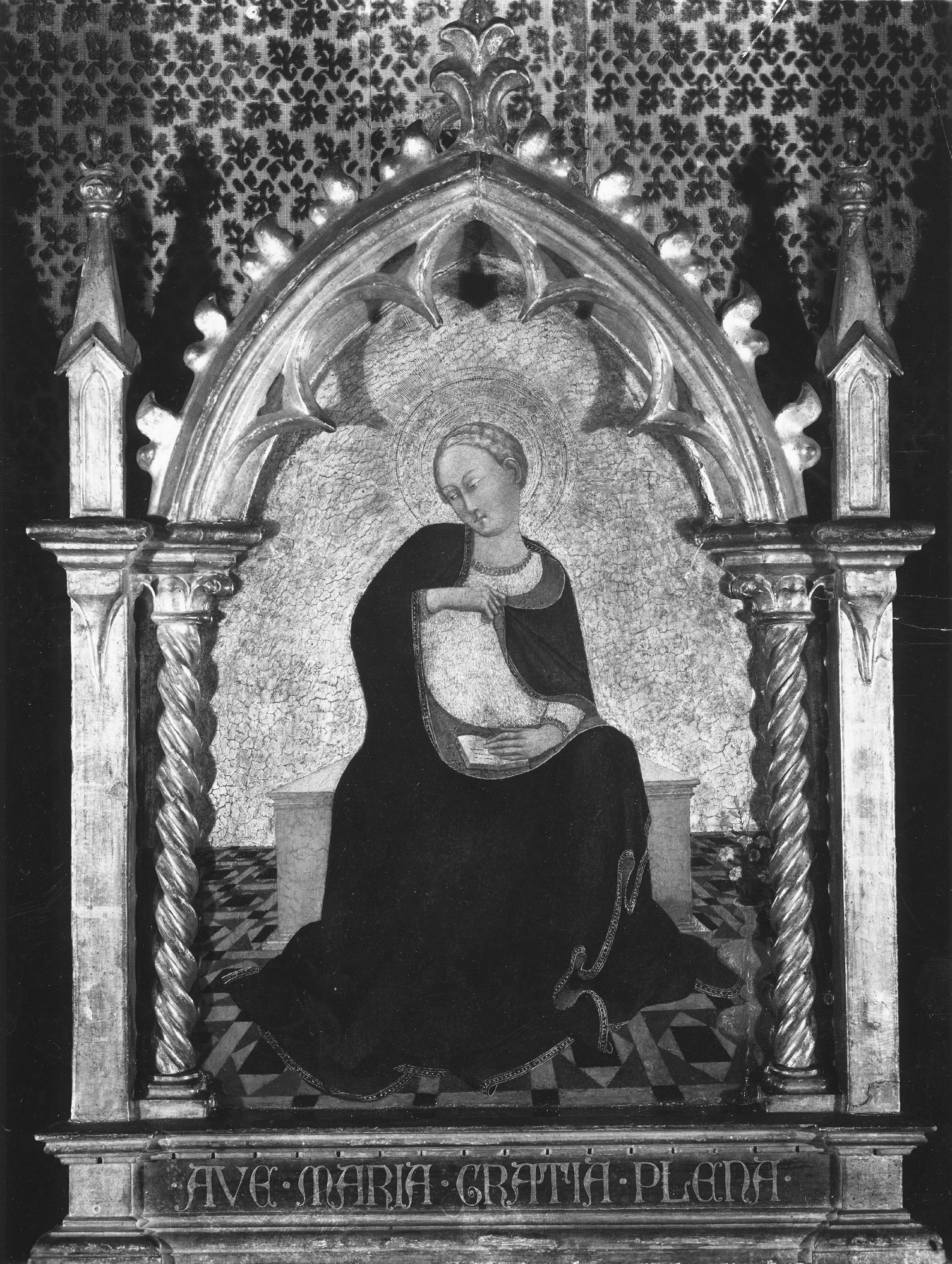

The panel support, of a vertical wood grain, is 2.8 centimeters thick and appears not to have been thinned. The original engaged frame moldings vary in depth from 4.8 to 6.5 centimeters at the top and measure 3.5 centimeters at the sides. The back of the panel has been painted with a thick gray coating, masking evidence of its carpentry, but a wide split in the front of the panel, 8.5 centimeters from its right edge, may follow a seam between two joined planks at that point. The gilding and paint surfaces are both severely abraded. The elongated shapes of original corbel supports are now revealed as exposed gesso beneath the spring of the framing arch at either side. Silver-leaf decoration in the pavement and beneath the Virgin’s draperies survives only as darkly stained bolus. Flesh tones are abraded to green underpaint. There is no record of the treatment that reduced the painting to this state, although it may be inferred that it occurred after 1970 and probably after 1972.1

From its earliest discovery and its subsequent publication by F. Mason Perkins in 1911, this panel has been universally recognized and admired as one of the rare surviving works by the premier artist of the Sienese quattrocento, Sassetta.2 Perkins reported that it had been found, presumably by Robert Langton Douglas, heavily overpainted in oils but that it had then been sensitively restored by an “expert hand,” assumed, probably correctly, to be Icilio Federico Joni.3 The restored state (fig. 1)—in which it was known to all scholars through the early 1970s—must have been scarcely less heavily overpainted than its previous condition, though undoubtedly more in an early Renaissance style. Its most recent cleaning was unnecessarily harsh but revealed passages of extreme delicacy and quality in parts of the paint surface. Modern spiral colonettes at either side of the picture field were removed during this cleaning, but the regilding of the frame, the structure of which is original, or other modern additions to it, like the central crocket at the top, were not addressed, exaggerating the contrast with the severely dilapidated appearance of the painted image.4

Perkins believed that the painting might originally have functioned as a pinnacle to the Madonna of the Snows altarpiece (fig. 2), documented as having been commissioned for the chapel of Saint Boniface in Siena Cathedral in 1430 and completed by 1432, and he therefore proposed a hypothetical provenance from Chiusdino, where the main panel of that altarpiece was then housed.5 In 1913 he submitted a brief notice to Rassegna d’arte calling attention to an Annunciatory Angel by Sassetta in Massa Marittima (fig. 3) that must have been a corresponding pinnacle from the opposite side of the same altarpiece. While the relationship of the Angel to the Virgin is self-evident, Perkins’s opinion that they were fragments of the Madonna of the Snows altarpiece was merely supposition; it was repeated, however, without challenge for the next forty years by all authors, who presumed that a missing central pinnacle representing the Blessing Redeemer might yet be found, as such a figure (although unaccompanied by an Annunciation group) is specified in Sassetta’s original contract.6 Although this reconstruction resurfaced sporadically in subsequent literature,7 it was contested by Federico Zeri in 1956 on the grounds that the essentially Renaissance, unified field structure of the Madonna of the Snows would not have been surmounted by three overtly Gothic pinnacles.8 Beyond the intellectual incongruity of such a juxtaposition, Zeri contended that the two known pinnacle panels are earlier in style than the Madonna of the Snows. Presuming them to be among Sassetta’s earliest works, he proposed instead that they formed part of the dispersed altarpiece painted between 1423 and 1426 for the Arte della Lana, most of the surviving fragments of which are today in the Pinacoteca Nazionale, Siena. Adding credibility to this proposal was the fact that two of the small pinnacles from the Arte della Lana altarpiece, representing half-length figures of the prophets Elijah and Elisha (fig. 4), are vaguely similar in shape to the Yale and Massa Marittima pinnacles.

Zeri’s argument was in part based on internal visual evidence and in part formulated to accommodate a full-length figure of Saint Anthony Abbot by Sassetta now in the collection of the Monte dei Paschi di Siena (fig. 5), which he and Roberto Longhi had recently discovered in a private collection in Florence. He wished to identify the Saint Anthony as one of two lateral panels to the Arte della Lana altarpiece—the other would have represented Saint Thomas Aquinas—as described in eighteenth-century sources, which also mention Annunciation pinnacles.9 Zeri’s argument was based on sound stylistic observations, but it was accepted in full only by Enzo Carli10 and was dispelled entirely in 1982, when the Musée du Louvre, Paris, acquired a full-length image of Saint Nicholas of Bari by Sassetta (fig. 6) that is obviously a companion to the Saint Anthony Abbot. Rejecting any association with the Arte della Lana altarpiece, Claudie Ressort elected to extend Zeri’s identification of the Yale and Massa Marittima panels as pinnacles to the newly discovered Saint Nicholas and the Saint Anthony Abbot.11 She also accepted John Pope-Hennessy’s opinion (in correspondence with her) that the two full-length Saints were later works by Sassetta, painted probably after the Madonna of the Snows altarpiece and, together with a fragmentary Madonna with Cherries in the Museo archeologico e d’arte della Maremma, Grosseto, possibly remnants of an altarpiece painted for the Petroni Chapel in San Francesco, Siena. Keith Christiansen, acknowledging that the Saint Nicholas and Saint Anthony Abbot cannot have been part of the Arte della Lana altarpiece but declining to speculate on alternative proposals for their origin, noted that the Saint Anthony panel is beveled at its top, tapering to a width too small to have accommodated the Yale or Massa Marittima pinnacles.12 He returned the pinnacles to the Madonna of the Snows altarpiece, notwithstanding physical evidence13—of which he may have been unaware—that the Madonna of the Snows did not have conventional pinnacles.

Machtelt Israëls, in her monographic study of the Madonna of the Snows altarpiece, definitively disassociated the Yale and Massa Marittima pinnacles from that structure.14 Initially, she agreed with Christiansen that they were not pertinent to the Louvre and Monte dei Paschi panels either, concluding that they were probably the “only remnants of an altarpiece of so far unknown provenance.” Revisiting the argument in 2010, she advanced evidence that both the Louvre and Monte dei Paschi panels have been trimmed on all sides, that the beveled truncation of the top of the Saint Anthony is not original, and that the structure of the composite wood planks of their supports matches that of the Yale and Massa Marittima pinnacles.15 The conclusion is unavoidable that these four works were painted on continuous wood supports and are parts of a single altarpiece. Israëls agreed with Zeri that they are early works by Sassetta, preceding the Madonna of the Snows altarpiece, but in her estimation, they are not likely to be as early as the Arte della Lana altarpiece. This seems to be correct, as is her observation that they cannot be associated with the Madonna of the Cherries in Grosseto, which was painted later in the decade of the 1430s.

Two proposals have been advanced to identify the original provenance of the altarpiece of which the Louvre, Monte dei Paschi, Yale, and Massa Marittima panels formed part. For Israëls, a likely candidate is the Petroni Chapel in San Francesco, Siena, which was described by Fabio Chigi in 1625 as containing an altarpiece signed by Sassetta.16 Although the surviving panels are not overtly Franciscan in iconography, Israëls argued that the uniformly deteriorated condition of all four fragments might be the result of a fire that ravaged the church in 1655 and that the Petroni altarpiece may have been commissioned by Francesca di Francesco di Spinello Tolomei to commemorate the name-saints of her deceased husband, Niccolaccio di Caterino Petroni, and her son, Antonio Petroni. An alternative suggestion by Roberto Bartalini links the two panels with an altarpiece described by Teofilo Gallacini (1564–1641) in the church of San Niccolò in Siena.17 Neither work is associated with a date in early sources. To these possibilities, Elena Marta Manzi adds a less probable third: a church in Massa Marittima, where the Angel pinnacle, the first of the four fragments to be rediscovered, was recorded as early as 1900.18 —LK

Published References

Perkins, F. Mason. “Dipinti italiani nella raccolta Platt.” Rassegna d’arte antica e moderne 11 (1911): 1–5, 145–49., 5, fig. 7; Perkins, F. Mason. “La pala d’altare del Sassetta a Chiusdino.” Rassegna d’arte 12 (1912): 196., 196; De Nicola, Giacomo. “Sassetta between 1423 and 1433—II.” Burlington Magazine 23, no. 125 (August 1913): 276–79, 282–83., 278, pl. 4, Q; Perkins, F. Mason. “A proposito della Pala del Sassetta a Chiusdino.” Rassegna d’arte antica e moderna 13 (1913): 40., 40; Crowe, Joseph Archer, and Giovanni Battista Cavalcaselle. A History of Painting in Italy, Umbria, Florence and Siena from the Second to the Sixteenth Century. Vols. 1–4, ed. Robert Langton Douglas. Vols. 5–6, ed. Tancred Borenius. London: J. Murray, 1903–14., 5:169–70n1; van Marle, Raimond. The Development of the Italian Schools of Painting. Vol. 9. The Hague: M. Nijhoff, 1927., 334–35, fig. 211; Venturi, Lionello. Pitture italiane in America. 2 vols. Milan: Ulrico Hoepli, 1931., pl. 111; Berenson, Bernard. Italian Pictures of the Renaissance: A List of the Principal Artists and Their Works with an Index of Places. Oxford: Clarendon, 1932., 512; Edgell, George Harold. A History of Sienese Painting. New York: Dial, 1932., 192, fig. 252; Venturi, Lionello. Italian Paintings in America. Trans. Countess Vanden Heuvel and Charles Marriott. 3 vols. New York: E. Weyhe, 1933., pl. 144; Berenson, Bernard. Pitture italiane del Rinascimento: Catalogo dei principali artisti e delle loro opera. Trans. Emilio Cecchi. Milan: Ulrico Hoepli, 1936., 440; Pope-Hennessy, John. Sassetta. London: Chatto and Windus, 1939., 27, 53n69; Venturi, Lionello. The Rabinowitz Collection. New York: Twin Editions, 1945., 13–14, pl. 7, fig. 2; Pope-Hennessy, John. Sienese Quattrocento Painting. London: Phaidon, 1947., 25; Zeri, Federico. “Towards a Reconstruction of Sassetta’s Arte della Lana Triptych (1423–6).” Burlington Magazine 98, no. 635 (February 1956): 36–39, 41., 36–39; Carli, Enzo. Sassetta e il Maestro dell’Osservanza. Milan: Aldo Martello, 1957., 12; Seymour, Charles, Jr. “Louis Mayer Rabinowitz.” Bulletin of the Associates in Fine Arts at Yale University 23, no. 3 (September 1957), 10–14., 13, fig. 4; “Recent Gifts and Purchases: February 22–December 31, 1959.” Yale University Art Gallery Bulletin 26, no. 1 (December 1960): 52–58., 53; Seymour, Charles, Jr. The Rabinowitz Collection of European Paintings. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1961., 22–23, 55; Berenson, Bernard. Italian Pictures of the Renaissance, A List of the Principal Artists and Their Works with an Index of Places: Central Italian and North Italian Schools. 3 vols. London: Phaidon, 1968., 1:386; Seymour, Charles, Jr. Early Italian Paintings in the Yale University Art Gallery. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1970., 206–7, 209, no. 156; Fredericksen, Burton B., and Federico Zeri. Census of Pre-Nineteenth-Century Italian Paintings in North American Public Collections. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1972., 183, 601; Ritchie, Andrew Carnduff, and Katharine B. Neilson. Selected Paintings and Sculpture from the Yale University Art Gallery. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1972., no. 9; Fahy, Everett. Review of Paintings from the Samuel H. Kress Collection: Italian Schools XII–XV Century, by Fern Rusk Shapley; Paintings from the Samuel H. Kress Collection: Italian Schools XV–XVI Century, by Fern Rusk Shapley; Early Italian Paintings in the Yale University Art Gallery, by Charles Seymour, Jr.; and Italian Primitives: The Case History of a Collection and Its Conservation, by Charles Seymour, Jr. Art Bulletin 56, no. 2 (June 1974): 283–85., 284; Blauwkuip, Lilian. “Sassetta’s Madonna della Neve altaarstuk.” Ph.D. diss., Rijksuniversiteit Groningen, 1980., 13; Claudie Ressort, in Foucart, Jacques, ed. Nouvelles acquisitions du Département de peintures (1980–1982). Paris: Ministère de la culture, Editions de la Réunion des musées nationaux, 1983.; van Os, Henk. Sienese Altarpieces, 1215–1460: Form, Content, Function. Vol. 1, 1215–1460. Groningen, Netherlands: Egbert Forsten, 1984., 167–68; Keith Christiansen, in Christiansen, Keith, Laurence Kanter, and Carl Brandon Strehlke. Painting in Renaissance Siena, 1420–1500. Exh. cat. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1988., 65; Mazzoni, Gianni. Quadri antichi del novecento. Vicenza: Neri Pozza, 2001., 304–5, 422, fig. 171; Israëls, Machtelt. Sassetta’s Madonna della Neve: An Image of Patronage. Leiden, Netherlands: Primavera Pers, 2003., 60–62, fig. 21; Machtelt Israëls, in Seidel, Max, et al., eds. Le arti a Siena nel primo Rinascimento: Da Jacopo della Quercia a Donatello. Exh. cat. Milan: Federico Motta, 2010., 232; Alessandro Bagnoli, in Semplici, Andrea, ed. Il museo di arte sacra a Massa Marittima. Arcidosso: Effigi, 2015., 77; Manzi, Elena Marta. “Stefano di Giovanni detto il Sassetta, 15. Angelo Annunciante.” In Il Sassetta e il suo tempo: Uno sguardo sull’arte senese del primo 1uattrocento, ed. Alessandro Bagnoli, 52–55. Exh. cat. Florence: Centro Di, 2024., 52–55

Notes

-

Despite the severity of the cleaning and the radical decision making it entailed, no mention of this treatment can be found in any files at the Yale University Art Gallery. The painting is described by Charles Seymour, Jr. (in Seymour, Charles, Jr. Early Italian Paintings in the Yale University Art Gallery. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1970., 207), as “not cleaned,” and it does not appear in Seymour, Charles, Jr., et al. Italian Primitives: The Case History of a Collection and Its Conservation. Exh. cat. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1972.. ↩︎

-

Perkins, F. Mason. “Dipinti italiani nella raccolta Platt.” Rassegna d’arte antica e moderne 11 (1911): 1–5, 145–49., 5, fig. 7. ↩︎

-

Mazzoni, Gianni. Quadri antichi del novecento. Vicenza: Neri Pozza, 2001., 304, citing Perkins, F. Mason. “Dipinti italiani nella raccolta Platt.” Rassegna d’arte antica e moderne 11 (1911): 1–5, 145–49., 4. ↩︎

-

Seymour believed the frame was modern; see Seymour, Charles, Jr. Early Italian Paintings in the Yale University Art Gallery. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1970., 207. ↩︎

-

Seymour confused the provenance of the Yale picture, claiming that it had remained in Italy, “perhaps at Chiusdino” (where it is not, in fact, recorded at any point), until 1936; see Seymour, Charles, Jr. Early Italian Paintings in the Yale University Art Gallery. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1970., 207. ↩︎

-

For the contract, see Israëls, Machtelt. Sassetta’s Madonna della Neve: An Image of Patronage. Leiden, Netherlands: Primavera Pers, 2003., 27. ↩︎

-

Seymour, Charles, Jr. “Louis Mayer Rabinowitz.” Bulletin of the Associates in Fine Arts at Yale University 23, no. 3 (September 1957), 10–14., 12; Seymour, Charles, Jr. Early Italian Paintings in the Yale University Art Gallery. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1970., 209; Ritchie, Andrew Carnduff, and Katharine B. Neilson. Selected Paintings and Sculpture from the Yale University Art Gallery. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1972., no. 9; and Keith Christiansen, in Christiansen, Keith, Laurence Kanter, and Carl Brandon Strehlke. Painting in Renaissance Siena, 1420–1500. Exh. cat. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1988., 65. ↩︎

-

Zeri, Federico. “Towards a Reconstruction of Sassetta’s Arte della Lana Triptych (1423–6).” Burlington Magazine 98, no. 635 (February 1956): 36–39, 41., 36–39. ↩︎

-

The altarpiece was described by the Abate Girolamo Carli, whose text is transcribed by John Pope-Hennessy, in Pope-Hennessy, John. Sassetta. London: Chatto and Windus, 1939., 6–7, 38n8. ↩︎

-

Carli, Enzo. Sassetta e il Maestro dell’Osservanza. Milan: Aldo Martello, 1957., 12. ↩︎

-

Claudie Ressort, in Foucart, Jacques, ed. Nouvelles acquisitions du Département de peintures (1980–1982). Paris: Ministère de la culture, Editions de la Réunion des musées nationaux, 1983.. ↩︎

-

Keith Christiansen, in Christiansen, Keith, Laurence Kanter, and Carl Brandon Strehlke. Painting in Renaissance Siena, 1420–1500. Exh. cat. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1988., 65. ↩︎

-

Blauwkuip, Lilian. “Sassetta’s Madonna della Neve altaarstuk.” Ph.D. diss., Rijksuniversiteit Groningen, 1980., 13. ↩︎

-

Israëls, Machtelt. Sassetta’s Madonna della Neve: An Image of Patronage. Leiden, Netherlands: Primavera Pers, 2003., 60–62. ↩︎

-

Machtelt Israëls, in Seidel, Max, et al., eds. Le arti a Siena nel primo Rinascimento: Da Jacopo della Quercia a Donatello. Exh. cat. Milan: Federico Motta, 2010., 232. ↩︎

-

Bacci, Pèleo. “L’elenco delle pitture, sculture e architetture di Siena, compilato nel 1625–26 da Mons. Fabio Chigi poi Alessandro VII.” Bullettino senese di storia patria 46 (1939): 297–337., 319. ↩︎

-

Roberto Bartalini, in Gurrieri, Francesco. La sede storica del Monte dei Paschi di Siena: Vicende costruttive e opere d’arte. Siena: Le Monnier, 1988., 297. See also Douglas, Robert Langton. “A Note on Recent Criticism of the Art of Sassetta.” Burlington Magazine 3, no. 9 (1903): 265–69, 272–73, 275., 275n3. Douglas referred to a manuscript copy of the Inscrizioni sanesi (vol. 2, p. 100), shown to him by Fairfax Murray but untraced today, to bolster his attribution to Sassetta of a small painting of the Virgin and Child in the rector’s quarters at the Manicomio di San Niccolò, then thought to be the work of Sano di Pietro. ↩︎

-

Manzi, Elena Marta. “Stefano di Giovanni detto il Sassetta, 15. Angelo Annunciante.” In Il Sassetta e il suo tempo: Uno sguardo sull’arte senese del primo 1uattrocento, ed. Alessandro Bagnoli, 52–55. Exh. cat. Florence: Centro Di, 2024., 54. ↩︎