Alexander Nesbitt, Esq. (1817–1886), London; sale, Christie’s, May 19, 1887, lot 180; Henry Wagner, London, by 1925; sale, Christie’s, January 16, 1925, lot 64; Robert Langton Douglas (1864–1951), London, 1925; Maitland Fuller Griggs (1872–1943), New York, 1925

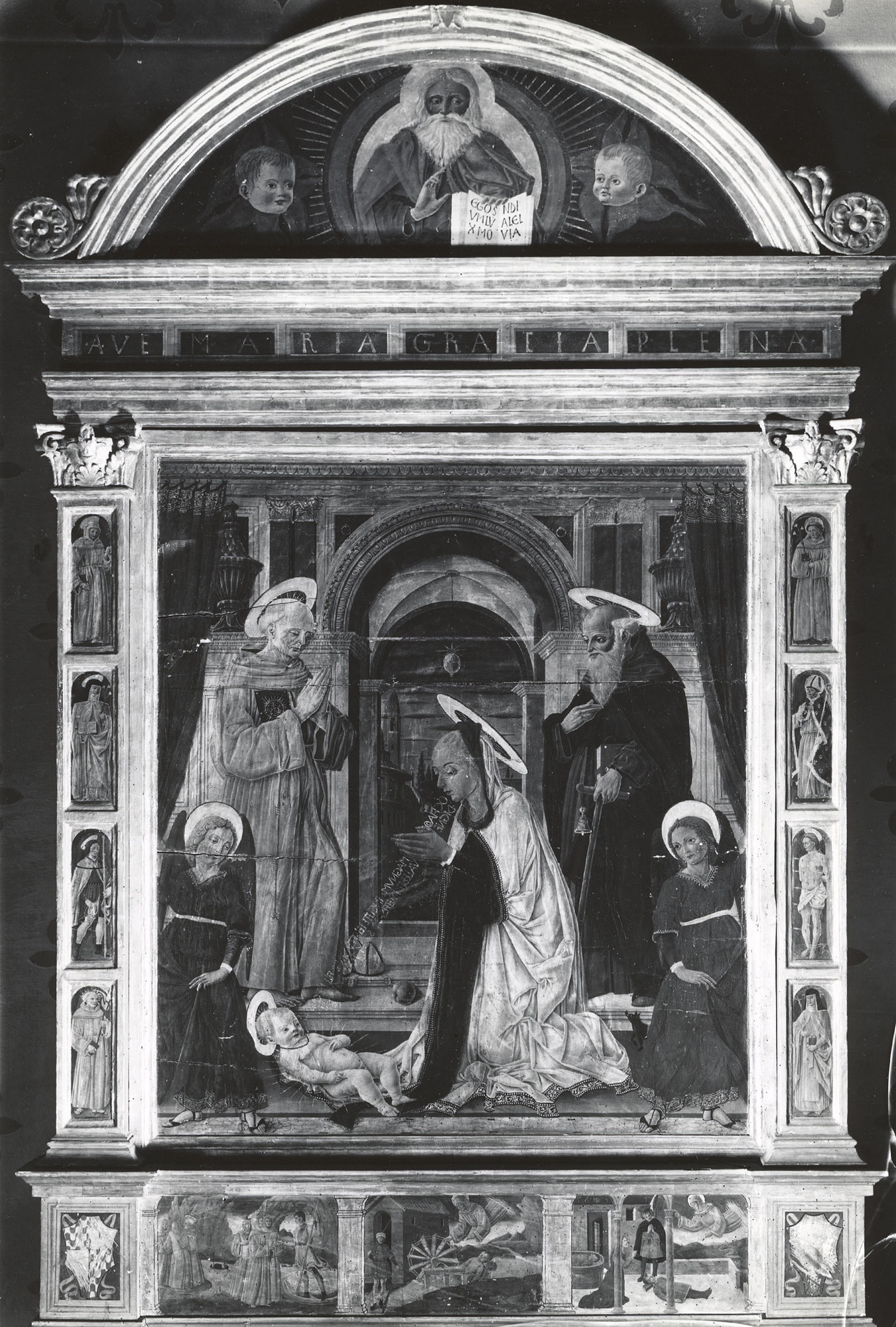

The panel support has been neither thinned nor cradled, retaining its original thickness of 2.4 to 2.8 centimeters. A barb along all four edges of the paint surface indicates that it has not been altered in size, although it has lost its original engaged frame moldings. Two splits in the panel, rising from the bottom edge approximately one-quarter the height of the image, have resulted in minor discreet paint losses in the Virgin’s blue robe. It was noted by Charles Seymour, Jr., that the painting had been liberally retouched before entering the collection at Yale.1 It was partially cleaned by Andrew Petryn in 1968 and more fully cleaned and retouched in 2000/2001 by Anne O’Connor. The second cleaning (fig. 1) revealed minimal abrasion but extensive flaking losses, through the red dresses of the Virgin and the angel at the right of the throne and along two vertical swaths of the Virgin’s blue robe: one following the shadow in the deep fold between her knees and one, longer and more extensive, running from her right knee along the profile of her robe to the pavement. These correspond to no structural flaws in the panel and may have resulted from old water damage. The Virgin’s face has been rubbed and has suffered from flaking losses, but the paint surface is otherwise well preserved. The mordant gilt decoration on the hems of the Virgin’s and angels’ robes is largely intact.

This painting first came to scholarly attention at the sale of Henry Wagner’s collection in London in 1925, where it bore an improbable attribution to Gentile da Fabriano. It may have been first associated with the Master of the Castello Nativity—an artistic personality isolated by Bernard Berenson in 19132—by Robert Langton Douglas, who purchased the painting at the Wagner sale. A label currently pasted on the back of the panel listing its two previous owners ascribes it to the Master of the Castello Nativity. It was published under that attribution by Raimond van Marle,3 presumably on the advice either of Douglas or of Berenson himself, who included it in his lists of 1932, 1936, and 1963.4 This attribution, which has been challenged only by Lionello Venturi, who gave the picture to the Master of San Miniato, deserves closer scrutiny.5

In his original compilation of works assigned to the Master of the Castello Nativity, Berenson asserted that the author of this group of paintings, primarily devotional images of the Virgin and Child, was an unknown Florentine artist active in the third quarter of the fifteenth century.6 He devised the conventional name for the Master from the most important member of the group: a relatively large colmo (tabernacle) depicting the Nativity or the Virgin Adoring the Christ Child, formerly in the Medici villa at Castello and now exhibited at the Galleria dell’Accademia in Florence (fig. 2). That painting retains its original frame, which is described in seventeenth-century inventories as bearing the arms (no longer legible) of Piero di Lorenzo de’ Medici and his wife, Lucrezia Tornabuoni, and which can therefore be dated sometime between their marriage in 1444 and Piero’s death in 1469. This range can be further delimited to the last decade of that span by the painting’s evident dependence on the composition of Filippo Lippi’s altarpiece of the Nativity from the Palazzo Medici (now Gemäldegalerie, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin7), of 1459. The core works attributed to the Master of the Castello Nativity all show a greater or lesser degree of dependence on Filippo Lippi in their style and, frequently, in borrowed motifs. Chiara Lachi, author of a doctoral thesis and the only published monograph on the artist, contended that the Master of the Castello Nativity first appeared as an independent painter as early as the mid-1440s and could be individuated before that among Lippi’s workshop assistants.8

For Lachi, the Yale painting must be considered among the earliest works by the Master of the Castello Nativity, datable to the late 1440s, alongside the Master’s only large-scale commission, an altarpiece depicting the Virgin and Child Enthroned with Saints Giusto and Clemente, now in the Museo dell’Opera del Duomo in Prato (fig. 3). The Prato altarpiece, which was first attributed to the Master of the Castello Nativity by Richard Offner in 1933,9 was removed from the high altar of the parish church of Santi Giusto e Clemente at Faltugnano near Prato. A document of 1450 recording the dispersal of small sums “per aiuto d’una tavola d’altare facta di nuovo in decta Chiesa” (for help with an altarpiece made recently in that church) has been interpreted as indicating a terminus ante quem for its execution, although it has also been objected that the amounts involved are far too small to be confidently associated with an altarpiece.10 Accepting an early date, Lachi suggested that the patron of the altarpiece may have been the rector of the church, ser Francesco di Stefano Ranaldeschi, who enjoyed the rights of jus patronatus there until his death in 1457. Carl Strehlke argued that the altarpiece must follow more closely the probable trajectory of the artist’s career, which he felt clustered around his name-piece in the 1460s. He proposed that the patron of the altarpiece was either a member of the Vinaccesi family, who held jus patronatus of the church between 1457 and 1468 or, more likely still, Gino di Lando Bonamici, whose arms are found in Santi Giusto e Clemente and who was awarded patronage there and of the nearby church of Santi Vito and Modesto in Soffignano or Susignano in 1468 by Pope Paul II, in recognition of the considerable sums Bonamici had committed to spend on the church’s restoration and embellishment.11

Pivotal to this difference of opinion is the hybrid, stylistically inconsistent nature of many of the works within the corpus of paintings generally accepted as by the Master of the Castello Nativity. One group of paintings, solidly if uninventively based on Filippo Lippi’s example, have been (probably correctly) recognized by both Lachi and Strehlke to relate so closely to the Master’s eponymous work that they are likely to be datable along with it to the 1460s, possibly extending into the early 1470s. A more inventive and original group of compositions—such as an extraordinary Virgin and Child with Four Angels in the Musée du Louvre, Paris (fig. 4)—was associated by Lachi, again probably correctly, with a hypothetical period of collaboration with Francesco Pesellino in the 1450s. The same author scattered a heterogeneous body of work between that period and a presumptive apprenticeship with Filippo Lippi in the 1440s. This last group includes the Faltugnano altarpiece (see fig. 3), the Yale painting, and another of the masterpieces attributed to this painter, a Madonna of Humility in the Museo Nazionale di San Matteo in Pisa (fig. 5). For Lachi, the dating of this group is anchored by the documentation for the Faltugnano altarpiece before 1450.

It is, however, impossible to believe that the architectural sophistication of the Faltugnano altarpiece, the spatial clarity of its compositional organization, or the witty originality of such devices as the marble angels serving as caryatids for the Virgin’s throne could have been conceived independently by so imitative a painter as the Master of the Castello Nativity at so early a date as the 1440s.12 The narrative complexity and spatial ingenuity of the four known panels from the predella of this altarpiece are also difficult to imagine without the previous example of Pesellino’s predella compositions of the 1450s.13 Furthermore, the flat, vacant expressions of the figures and the stiff linearity of their execution is strikingly at odds with the coloristic virtuosity, rigorously consistent lighting, and faultless foreshortening of all the details of the setting, leading to the suspicion that this work, too, is collaborative and that its intelligent design may be due to Pesellino, not to the Master of the Castello Nativity. Such a collaboration must explain the luxurious surface effects and aggressive novelty of the composition of the Pisa Madonna of Humility (see fig. 5) as well. Neither it nor the Faltugnano altarpiece can logically be datable earlier than the mid-1450s.

Lachi, accepting that the Master of the Castello Nativity must have collaborated with Pesellino at some point in his career—in her estimation, sometime after leaving Filippo Lippi’s workshop—noted that, in 1453, Pesellino entered into a partnership, or compagnia, with two other painters, Piero di Lorenzo di Pratese and Zanobi di Migliore.14 She defended a claim that the former might be the Master of the Castello Nativity since a certain “Piero di Lorenzo” appears among the names of artists working alongside Filippo Lippi on the Maringhi Coronation of the Virgin in 1441.15 As Piero di Lorenzo di Pratese is known to have been born between 1410 and 1414, antedating the beginnings of his career to the 1440s or even earlier would not be exceptional, but Lachi’s thesis has not been universally accepted. Annamaria Bernacchioni advanced evidence that the Piero di Lorenzo named in Lippi’s shop was a gilder, not a painter, and therefore could not be the same person as Piero di Lorenzo di Pratese.16 The identification of the Master of the Castello Nativity, however, does not depend on a putative appearance within the workshop of Filippo Lippi. The recurrent type of round-faced and summarily rendered figure found in several of Lippi’s works of the 1440s bears only a generic resemblance to independent paintings by the Master of the Castello Nativity: they are not attributable to him but were undoubtedly inspirational for him. The identification of Piero di Lorenzo di Pratese with the Master of the Castello Nativity or, following Bernacchioni, with the artist conventionally known as the Pseudo-Pier Francesco Fiorentino is entirely based on circumstantial but not demonstrable argument.17

An alternative proposal by the present author18 that one of Pesellino’s compagni, either Piero di Lorenzo di Pratese or Zanobi di Migliore, was probably the artist responsible for two panels from an altarpiece triptych in the State Hermitage Museum, Saint Petersburg, showing Saint Sylvester Enthroned (fig. 6) and the Baptism of Constantine (fig. 7), as well as a related panel of the Crucifixion in the Musée du Petit Palais, Avignon, France,19 has not elicited comment in the literature. Reconstructing the Hermitage triptych as having been completed by Pesellino’s three predella panels showing episodes from the life of Saint Sylvester,20 the author supposed the works could be dated to the period of the compagnia, between 1453 and 1457, and also assigned responsibility for the Hermitage and Avignon panels to the Master of the Castello Nativity, based on the repetition of figural idiosyncrasies—specifically the pinched facial features with close-set eyes, upturned nose, and pursed lips—that characterize some of the latter’s works. This identification was too broad, however. Those features are undeniably similar but only occur in a limited number of works attributed to the Master of the Castello Nativity, above all in the Faltugnano (see fig. 3), Pisa (fig. 5), and Yale panels. Not only would this observation reinforce an argument for dating those paintings after 1453, but also it may indicate grounds for suggesting they could be the work of Pesellino’s second-named partner, Zanobi di Migliore. No signed or fully documented works survive by Zanobi di Migliore, who is known to have left the partnership with Pesellino sometime before 1457 and to have emigrated from Florence to Bologna in 1459.21 An altarpiece of the Virgin Adoring the Christ Child with Saints Bernardino and Anthony Abbot in the Pinacoteca Communale in Bologna (fig. 8), bearing the Bentivoglio arms quartered with Sforza on the pilaster bases of its original tabernacle frame, has been credibly attributed to Zanobi di Migliore.22 This painting, redolent of both Emilian and Florentine cultural influences, bears more than a casual relationship in its figure style to the Yale and Pisa paintings.

If the Pisa and Faltugnano panels are indeed the work of Zanobi di Migliore in collaboration with Francesco Pesellino, it would be reasonable to propose a date for them shortly after 1453, certainly earlier than 1457. If this were so, another painting probably to be considered alongside them as attributable to Zanobi di Migliore might be the Virgin and Child Enthroned in Dresden, Germany (fig. 9), generally attributed to Pesellino. Unlike these, the Yale panel shows no obvious indication of Pesellino’s active participation, either in its design or in its execution: the design of the Yale painting is ambitious, although by comparison to the Faltugnano altarpiece somewhat tentative, while its execution is uniformly flat and uninspired—in some passages, such as the faces and hands of the two angels, insipid. It could very well represent Zanobi’s output after leaving the compagnia with Pesellino and Piero di Lorenzo di Pratese and could therefore plausibly be dated from sometime before 1457 to not later than 1459. A possible terminus a quo might be adduced by the resemblance of the decorative inlays of the Virgin’s throne to motifs employed by Luca della Robbia in the enamel terracotta frame of the tomb of Bishop Benozzo Federighi, installed in San Pancrazio in Fiesole in 1458 or 1459 (moved to Santa Trinita, Florence, in the eighteenth century). The resemblance is not so close as to predicate a dependence of one upon the other, but they are both equally unlike any other Florentine architectural precedents. —LK

Published References

van Marle, Raimond. The Development of the Italian Schools of Painting. Vol. 11. The Hague: M. Nijhoff, 1929., 300, 305; Exhibition of Italian Primitive Paintings, Selected from the Collection of Maitland F. Griggs. Exh. cat. New York: Century Association, 1930., no. 3; Venturi, Lionello. Pitture italiane in America. 2 vols. Milan: Ulrico Hoepli, 1931., pl. 190; Berenson, Bernard. Italian Pictures of the Renaissance: A List of the Principal Artists and Their Works with an Index of Places. Oxford: Clarendon, 1932., 343; Berenson, Bernard. Pitture italiane del Rinascimento: Catalogo dei principali artisti e delle loro opera. Trans. Emilio Cecchi. Milan: Ulrico Hoepli, 1936., 280; Lipman, Jean. “Three Profile Portraits by the Master of the Castello Nativity.” Art in America 24, no. 3 (1936): 110–26., 113; Valentiner, Rudolf W. “Andrea dell’Aquila, Painter and Sculptor.” Art Bulletin 19 (1937): 503–36., 535, fig. 40; Kennedy, Ruth Wedgewood. Alessio Baldovinetti: A Critical and Historical Study. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1938., 12; Salmi, Mario. “La Madonna ‘dantesca’ del Museo di Livorno e il ‘Maestro della Natività di Castello.’” Liburni civitas 11, nos. 5–6 (1938): 217–56., 243–44, fig. 24; S[izer], T[heodore]. “The Yale Collection of Early Italian Painting.” Bulletin of the Associates in Fine Arts at Yale University 13, no. 3 (June 1945): 2–4, 7., 3; Hess, Albert G. Italian Renaissance Paintings with Musical Subjects: A Corpus of Such Works in American Collections, with Detailed Descriptions of the Musical Features. New York: Libra, 1955., no. 85; Berenson, Bernard. Italian Pictures of the Renaissance, A List of the Principal Artists and Their Works with an Index of Places: The Florentine School. 2 vols. London: Phaidon, 1963., 1:142; Seymour, Charles, Jr. Early Italian Paintings in the Yale University Art Gallery. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1970., 160, 316, no. 114; Fredericksen, Burton B., and Federico Zeri. Census of Pre-Nineteenth-Century Italian Paintings in North American Public Collections. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1972., 600; Lachi, Chiara. Il Maestro della Natività di Castello. Florence: Edifir, 1995., 62–63, 100

Notes

-

Seymour, Charles, Jr. Early Italian Paintings in the Yale University Art Gallery. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1970., 160, no. 114. ↩︎

-

Berenson, Bernard. Catalogue of a Collection of Paintings and Some Art Objects. Vol. 1, Italian Paintings. Philadelphia: John G. Johnson, 1913., 17–19. ↩︎

-

van Marle, Raimond. The Development of the Italian Schools of Painting. Vol. 11. The Hague: M. Nijhoff, 1929., 300. ↩︎

-

Berenson, Bernard. Italian Pictures of the Renaissance: A List of the Principal Artists and Their Works with an Index of Places. Oxford: Clarendon, 1932., 343; Berenson, Bernard. Pitture italiane del Rinascimento: Catalogo dei principali artisti e delle loro opera. Trans. Emilio Cecchi. Milan: Ulrico Hoepli, 1936., 280; and Berenson, Bernard. Italian Pictures of the Renaissance, A List of the Principal Artists and Their Works with an Index of Places: The Florentine School. 2 vols. London: Phaidon, 1963., 1:142. ↩︎

-

Venturi, Lionello. Pitture italiane in America. 2 vols. Milan: Ulrico Hoepli, 1931., pl. 190. ↩︎

-

Berenson, Bernard. Catalogue of a Collection of Paintings and Some Art Objects. Vol. 1, Italian Paintings. Philadelphia: John G. Johnson, 1913., 17–19. ↩︎

-

Inv. no. 69, https://id.smb.museum/object/864730. ↩︎

-

Lachi, Chiara. Il Maestro della Natività di Castello. Florence: Edifir, 1995., 15–21. ↩︎

-

Offner, Richard. “La mostra del Tesoro di Firenze sacra—II.” Burlington Magazine 63, no. 367 (October 1933): 166–78., 177–78. ↩︎

-

Matteo Mazzalupi, in De Marchi, Andrea, and Cristina Gnoni Mavarelli, eds. Da Donatello a Lippi: Officina Pratese. Milan: Skira, 2013., 176–79, accepted a date before 1450 for the Faltugnano altarpiece. Carl Brandon Strehlke, in Strehlke, Carl Brandon. Italian Paintings, 1250–1450, in the John G. Johnson Collection and the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Philadelphia: Philadelphia Museum of Art, 2004., 279, did not, believing the altarpiece to be as much as two decades later in date. Keith Christiansen, in Christiansen, Keith. “An Addition to the Reconstruction of the Faltugnano Altarpiece of the Master of the Castello Nativity.” In Officina Pratese: Tecnica, stile, storia, 399–402. Florence: Edifir, 2014., 399–402, offered no opinion on dating. ↩︎

-

Strehlke, Carl Brandon. Italian Paintings, 1250–1450, in the John G. Johnson Collection and the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Philadelphia: Philadelphia Museum of Art, 2004., 278, cites the date as “1469 modern style”; Matteo Mazzalupi, in De Marchi, Andrea, and Cristina Gnoni Mavarelli, eds. Da Donatello a Lippi: Officina Pratese. Milan: Skira, 2013., 177–78, retains the date 1468 as recorded in the document. ↩︎

-

Gigetta Dalli Regoli, in Dalli Regoli, Gigetta. “Il Maestro di San Miniato: anatomia di un’ipotesi.” In Il “Maestro di San Miniato”: Lo stato degli studi, i problemi, le risposte della filologia, ed. Federico Zeri and Gigetta Dalli Regoli, 17–124. Pisa: Giardini, 1988., 29, called attention to reflections of the throne in the Faltugnano altarpiece appearing in works by Neri di Bicci of the later 1450s (see Szépűvészeti Múzeum, Budapest, inv. no. 1228 [63]) and 1460s. ↩︎

-

For the predella panels, see National Gallery, London, inv. no. NG3648, https://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/paintings/master-of-the-castello-nativity-the-nativity; Philadelphia Museum of Art, inv. nos. 24–25, https://philamuseum.org/collection/object/101990, https://philamuseum.org/collection/object/102005; and Cassa di Risparmio di Prato. ↩︎

-

The documents from the Florentine Tribunale di Mercanzia concerning this compagnia were published by Pèleo Bacci; see Bacci, Pèleo. “Il Pesellino, Fra Filippo Lippi, Domenico Veneziano, Piero di Lorenzo, Fra Diamante, Domenico discepolo di Fra Filippo, etc. e la tavola pistajese della ‘Trinità’ nella Galleria Nazionale di Londra.” * Le Arti [Bolletino d’arte]* 3, no. 5 (June–July 1941): 353–70., 364–65. ↩︎

-

Gallerie degli Uffizi, Florence, inv. no. 1890 n. 8352, https://catalogo.uffizi.it/it/29/ricera/detailiccd/1187616/. ↩︎

-

Cited in Di Lorenzo, Andrea. “Documents in the Florentine Archives.” In From Filippo Lippi to Piero della Francesca: Fra Carnevale and the Making of a Renaissance Master, ed. Keith Christiansen et al., 290–98. Exh. cat. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2005., 290–93. Bernacchioni and Megan Holmes offered an alternative thesis that Piero di Lorenzo di Pratese may be one of the hands in the workshop identified by modern scholarship as the “Pseudo-Pier Francesco Fiorentino.” See Bernacchioni, Annamaria. “Le forme della tradizione: Pittori fra continuità e innovazione.” In Maestri e botteghe: Pittura a Firenze alla fine del quattrocento, ed. Mina Gregori, Antonio Paolucci, and Cristina Acidini Luchinat, 171–80. Exh. cat. Milan: Silvana, 1992., 171–80; and Holmes, Megan. Fra Filippo Lippi: The Carmelite Painter. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1999., 270n135. ↩︎

-

For the Pseudo-Pier Francesco Fiorentino, see Yale University Art Gallery, inv. nos. 1871.43, https://artgallery.yale.edu/collections/objects/301; and 1943.225, https://artgallery.yale.edu/collections/objects/45030. ↩︎

-

Laurence Kanter, in Kanter, Laurence, and Pia Palladino, eds. Fra Angelico. Exh. cat. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2005., 287. ↩︎

-

Inv. no. 20199. ↩︎

-

Worcester Art Museum, Mass., inv. no. 1916.12, https://worcester.emuseum.com/objects/6232/a-miracle-of-saint-silvester?ctx=719d54f021ccbf8f4cd063b94c3f9ecc5bf4e733&idx=0; and Galleria Doria Pamphilij, Rome. ↩︎

-

Filippini, Francesco, and Guido Zucchini. Miniatori e pittori a Bologna: Documenti del secolo XV. Rome: Accademia nazionale dei Lincei, 1968., 168–69. Zanobi di Migliore had transferred to Bologna with his family (his wife, five children, and sister-in-law) by March 29, 1459, and matriculated in the painters’ guild there on October 12, 1461. He is named in Bolognese documents at intervals through December 1468. Presumably, he returned to Florence at some date after that, as he is mentioned in Neri di Bicci’s Ricordanze on February 17, 1475, when Neri was called upon to arbitrate a dispute between Zanobi di Migliore, “dipintore tra’ Pellic[i]ai,” and Bernardo di Giovanni Rustichi over the price of “certe ispalliere da forzieri detto Zanobi aveva dipinte a detto Bernardo” (certain spalliere [painted backing boards] from chests that he said Zanobi painted for the said Bernardo). Zanobi died sometime that year, as he is described as quondam (former [i.e., deceased]) in the matriculation of his son Bartolomeo in the painters’ guild of Bologna. ↩︎

-

Filippini, Francesco. “Notizie di pittori fiorentini a Bologna nel Quattrocento.” In Miscellanea di Storia dell’Arte in onore di I. B. Supino, 417–28. Florence: Leo S. Olschki, 1933., 419–23. ↩︎