San Salvi(?), Florence;1 James Jackson Jarves (1818–1888), Florence, by 1859

The panel support, of a vertical grain, has been thinned to a depth of 1 centimeter and cradled. It is comprised of three planks, 20.5, 18.5, and 8 centimeters wide, left to right; the leftmost plank is 5 millimeters wider at the bottom than it is at the top. The two panel joins have separated slightly, but neither gap has provoked any measurable paint loss. A minor split extends 5 centimeters from the top of the panel through the halo of Saint Francis, nearly on center. The panel was regilt before entering Yale’s collection in 1871, but the new gold and any original gold or bolus it may have covered were scraped away in a cleaning by Andrew Petryn in 1967, leaving only roughly scratched gesso. Slivers of original gold can be seen beneath the profiles and along the edges of the robes of all three figures, and islands of original gilding survive in the haloes, surrounded by broad stretches of exposed bolus. The halo of Saint Zenobius is 2 centimeters smaller in diameter (13.5 cm) than those of the other two saints (15.5 cm) and lacks the undecorated central disk that features in the latter. A barb of gesso and paint is visible along the bottom and right edges of the picture surface, while small losses at the upper-left and -right corners suggest the positioning of corbels or capitals that might have supported an arched top to the panel. No pattern of damage survives at the top center that might indicate whether this arch was single or double. The paint surface is well preserved, though lightly and evenly abraded. Minor losses, chiefly in Saint Zenobius’s book and index finger and in the robes of Saints Zenobius and Francis, were retouched by Anne O’Connor during a treatment in 2003. The only significant loss, at the top of Zenobius’s miter, was not reconstructed.

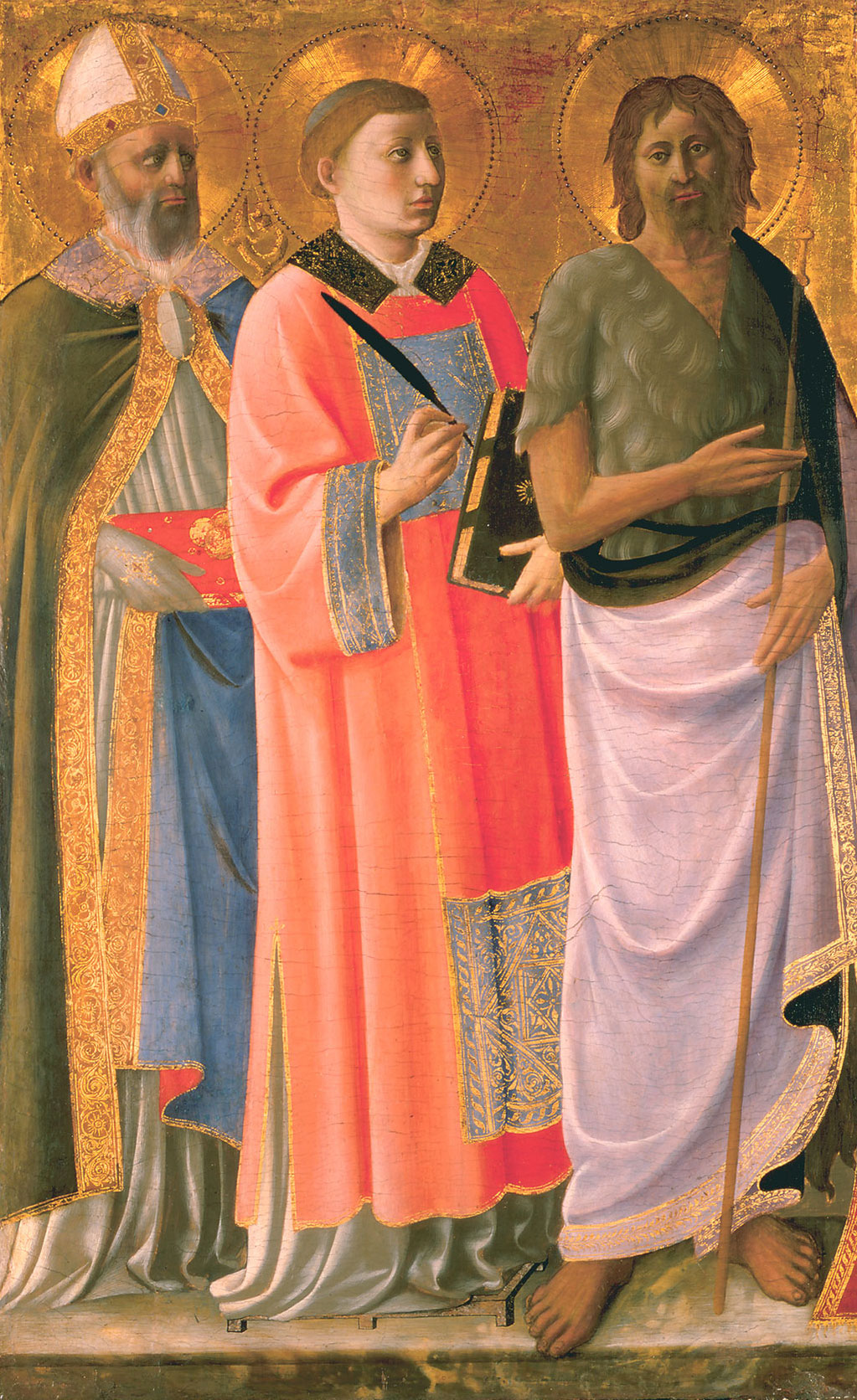

Three full-length saints standing on a variegated marble pavement and turned three-quarters to the viewer’s left are ranged one behind the other, looking intently before them and slightly upward. The leftmost figure, notionally in front of the other two saints, is a bishop in a white surplice; over this, he wears a green cope lined with red. He holds a blue book in his left hand, while his right hand, presumably holding a crozier, is cropped at the left edge of the panel. He is identifiable as Saint Zenobius, patron saint of Florence, by the large red fleur-de-lis glazed onto the gilt morse fastened at his breast. Behind him stand two Franciscans: Saint Francis, dressed in a brown habit, the marks of the stigmata visible on his hands and feet and a small gold processional cross held lightly in his right fingertips, and Saint Anthony of Padua, wearing a gray habit and holding a bright red flame in his left hand.

The Yale panel is evidently the right lateral panel of a modest-sized altarpiece. The companion lateral from the left side of the altarpiece was recognized in the early years of the twentieth century by Robert Langton Douglas as a painting of Saints John the Baptist, Lawrence, and Nicholas of Bari then in the Sidney collection at Richmond, England, now in the Hyde Collection at Glens Falls, New York (fig. 1). The two panels correspond closely in size and exactly in format; the three saints in the Hyde panel are turned toward the viewer’s right, the Baptist gesturing at and Saints Lawrence and Nicholas looking toward the subject of the missing central panel of the complex, presumably a Virgin and Child Enthroned. The latter was identified in 2005 by Pia Palladino as a panel in the State Hermitage Museum, Saint Petersburg (fig. 2). The lining of Saint Zenobius’s cloak, cropped at the left edge of the Yale panel, appears along the right edge of the painting in Saint Petersburg, while the extended ends of the red carpet beneath the Virgin’s throne in that painting appear on the pavement at the left and right edges of, respectively, the Yale and Hyde panels. The background of the Hermitage Virgin and Child is overpainted black (probably covering the head of Saint Zenobius’s crozier), and a 1938 photograph of the Hyde panel shows that its background, too, had been overpainted black before a more recent cleaning revealed its present, modern gilding.2

The Hermitage panel was largely unknown to art-historical literature prior to 2005. The lateral panels at Yale and in the Hyde Collection were known under a variety of attributions, reflecting the then-prevalent attitudes toward all works emerging from the workshop and following of Fra Angelico. Catalogued by James Jackson Jarves and Russell Sturgis, Jr., as by Angelico,3 the Yale panel was published repeatedly by Osvald Sirén,4 followed by Richard Offner,5 as by Andrea di Giusto, an imitator of Angelico to whom was assigned a large and heterogeneous array of works varying widely in quality. These works had in common among them only that they were less close to Angelico’s style than were those of another follower who was at that time identified as Zanobi Strozzi. The latter group of paintings, in turn, have nearly all come to be recognized as early works by Fra Angelico, quite distinct from Strozzi’s documented production as a miniaturist, but his name clung to the majority of them until as recently as the 1970s. Bernard Berenson isolated a distinct body of work, including the Yale panel, within the large category once labeled “Andrea di Giusto,” and maintaining its divergence from both the known works of Andrea di Giusto and the presumed works of Zanobi Strozzi, he labeled them as by Domenico di Michelino.6 Federico Zeri later realized that Domenico di Michelino could not have been their author, but respecting the integrity of Berenson’s grouping, he rebaptized the artist the “Pseudo-Domenico di Michelino.”7 Roberto Longhi, unwilling to acknowledge any contention of Berenson’s, selected a different name-piece for the same group, coining the pseudonym “Master of the Buckingham Palace Madonna,” a proposal adopted by Seymour.8 Attempts by Mario Salmi and Licia Collobi Ragghianti to reconcile Berenson’s Domenico di Michelino group with the historical personality of Zanobi Strozzi were marred by those authors’ persistence in believing that the early works by Angelico that had traditionally been labeled as Zanobi Strozzi were an integral part of the combined oeuvre.9 An essential step forward was made possible by the pioneering views of Angelico’s early career published by Miklós Boskovits in the 1970s,10 but it was only in 1998, with the discovery of a crypto-signature on one of his paintings in the National Gallery, London,11 that a clear image of Zanobi Strozzi as a panel painter emerged, revealing him to be more or less identical with the artist who had previously been discussed as Domenico di Michelino, the Pseudo-Domenico di Michelino, or the Master of the Buckingham Palace Madonna.12 Both parallel investigations—into the work of Fra Angelico and Zanobi Strozzi—have been pursued vigorously since, following exhibitions in New York (1994, 2005), Milan (2001), Florence (2003), and elsewhere.13

When the Yale and Hyde panels were reunited at the Fra Angelico exhibition in New York in 2005, it was suggested that minor but closely similar damages at their upper-left and -right corners might have been caused by the removal at those points of corbels from framing arches. The altarpiece was reconstructed in a format loosely related to that of Fra Angelico’s Guidalotti polyptych in Perugia, and like that structure, it was presumed to have been completed by a narrative predella. Two of the three panels of such a predella were identified: a Nativity in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (fig. 3), and an Adoration of the Magi in the National Gallery, London (fig. 4). These two panels are, to within one centimeter, the same widths as the Hermitage and Yale panels, respectively, beneath which they would once have stood. The missing third panel of the predella has not yet come to light. Its subject is likely to have been the Annunciation, but any other scene from the infancy of Christ or the life of the Virgin is at least theoretically possible as well.

The 2005 exhibition catalogue assigned to the five panels of this reconstructed altarpiece a date of ca. 1435–40, based on two related threads of logic.14 The composition of the Hermitage panel, with the Christ Child standing frontally on the Virgin’s lap, holding a globe before Him in His left hand and blessing with His right, is based on that of the center panel of Fra Angelico’s Linaiuoli Tabernacle of 1433–36.15 It was assumed that this span of years represented not only a terminus post quem but also a terminus a quo, since this was the period of Strozzi’s closest collaboration with Angelico. Furthermore, passages in the two predella panels in London and New York, specifically the ring of angels at the top of the latter and the Virgin, Child, and Saint Joseph at the right of the former, were judged to be of sufficient quality to indicate the possible direct intervention of Fra Angelico in their design or painting. If this were true, it would also argue for a period of execution before Angelico’s transfer from Fiesole—where the two artists lived near each other and worked in the same studio spaces—to San Marco in Florence around 1442. It did not, however, take sufficiently into consideration the internal development of Zanobi Strozzi’s style. The Hermitage panel bears no meaningful resemblance to Strozzi’s earliest-known images of the Virgin and Child, the so-called Buckingham Palace Madonna and the Virgin and Child with Four Saints formerly in the Alana Collection, Delaware, nor does it relate to the Santa Maria Nuova altarpiece by Strozzi, datable on the basis of documents to 1434–39.16 The latter, like the Hermitage panel, also borrows its imagery from Angelico’s Linaiuoli Tabernacle, but the result is far less classicizing, with flatter and more simply drawn forms, a shallower sense of space, and a brighter, more artificial palette.

The predella panels, for all their evident quality, are entirely the invention and work of Zanobi Strozzi; it would be misleading to tie their dating to biographical events in Fra Angelico’s life. The types, mannerisms, and actions of the retinue of the Magi at the left of the London panel (see fig. 4) recall the figures in Strozzi’s predella scenes relating the legend of Saints Cosmas and Damian, painted for the Annalena altarpiece now in the Museo di San Marco, Florence.17 Although many scholars believe that altarpiece to be a work by Fra Angelico from the early 1430s, it was correctly observed by John Pope-Hennessy that the predella scenes cannot precede those in Angelico’s predella to the San Marco high altarpiece of 1441–44, on which their compositions are closely modeled.18 The coarse simplification of action, blunting of detail, and misunderstanding of both spatial relationships and narrative nuance in them must represent a dependence upon, rather than a preparatory stage leading up to, the San Marco predella. A case has been made on iconographic as well as formal grounds for considering the Annalena altarpiece a work carried out by Zanobi Strozzi, presumably over Angelico’s designs, during one of the Dominican artist’s two absences from Florence, after 1445 or after 1452.19 The later of these two time spans would account for the adoption, in the background of the altarpiece, of architectural solutions developed by Angelico only after 1445, in his frescoes in the Cappella Niccolina at the Vatican.

It is precisely in this period—after 1445—that documents concerning Strozzi’s practice as a manuscript illuminator become plentiful and the development of his painting style can be charted with some accuracy. Among the San Marco choir books, for example, for which Strozzi received payments between 1446 and 1454, the images most closely related to the figure types in the Yale, Hyde, Hermitage, Metropolitan Museum, and London panels are those in Gradual A (fig. 5), painted by Strozzi between September 1448 and March 1449.20 Also related to these panels are the four cut-out illuminations from a Benedictine breviary now divided between the Metropolitan Museum of Art (fig. 6); the Wallraf-Richartz Museum, in Cologne, Germany; the Cini Foundation, in Venice; and a private collection, for which Strozzi received payment in 1450.21 It is reasonable to assume that this narrow window, the years between or around 1448 and 1450, is a far more likely period in which to place the execution of the Yale altarpiece than any period significantly earlier or significantly later.

The presence of Saints Francis and Anthony of Padua in the Yale panel makes a Franciscan provenance for the altarpiece all but a certainty, while the prominence closest to the Virgin’s throne of Saints Zenobius and John the Baptist, both patrons of Florence, argues for a Franciscan establishment in that city. The reputed provenance of the Yale panel from the church of San Salvi, formerly an Augustinian monastery, must at best be incidental. San Salvi, secularized during the Napoleonic suppressions of ecclesiastical and monastic property, was used through the nineteenth century as a collection-point depot for works of art removed from churches and confraternities throughout the Florentine district. As the provenance from San Salvi is unconfirmed, it is at least notionally possible, as well, that the record was a mistaken transcription for San Salvatore, a Franciscan convent on the hill below San Miniato al Monte in Florence, for which Zanobi Strozzi also painted the signed altarpiece of the Annunciation now in the National Gallery, London.22 Saints Lawrence and Nicholas at the left of the Hyde panel must, in some combination, refer to the name and patronymic of the unknown donor or to the dedication of the chapel in which the altarpiece stood. —LK

Published References

Jarves, James Jackson. Descriptive Catalogue of “Old Masters” Collected by James J. Jarves to Illustrate the History of Painting from A.D. 1200 to the Best Periods of Italian Art. Cambridge, Mass.: H. O. Houghton, 1860., 47, no. 41; Sturgis, Russell, Jr. Manual of the Jarves Collection of Early Italian Pictures. New Haven: Yale College, 1868., 46; Venturi, Adolfo. Storia dell’arte italiana. 11 vols. Milan: Ulrico Hoepli, 1901–40., 7, pt. 1: 28–29n5; Sirén, Osvald. “Trecento Pictures in American Collections—III.” Burlington Magazine 14, no. 71 (February 1909): 325–26., 326, pl. 2, no. 1; Crowe, Joseph Archer, and Giovanni Battista Cavalcaselle. A History of Painting in Italy, Umbria, Florence and Siena from the Second to the Sixteenth Century. Vols. 1–4, ed. Robert Langton Douglas. Vols. 5–6, ed. Tancred Borenius. London: J. Murray, 1903–14., 4:64–65n2; Sirén, Osvald. A Descriptive Catalogue of the Pictures in the Jarves Collection Belonging to Yale University. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1916., 79–80, no. 31; Offner, Richard. Italian Primitives at Yale University: Comments and Revisions. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1927., 5; Berenson, Bernard. Italian Pictures of the Renaissance: A List of the Principal Artists and Their Works with an Index of Places. Oxford: Clarendon, 1932., 365; Berenson, Bernard. Italian Pictures of the Renaissance, A List of the Principal Artists and Their Works with an Index of Places: The Florentine School. 2 vols. London: Phaidon, 1963., 1:68; Seymour, Charles, Jr. Early Italian Paintings in the Yale University Art Gallery. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1970., 159, 316, no. 113; Fredericksen, Burton B., and Federico Zeri. Census of Pre-Nineteenth-Century Italian Paintings in North American Public Collections. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1972., 599; Kettlewell, James K. Hyde Collection Catalogue. Glens Falls, N.Y.: Hyde Collection, 1981., 19; Laurence Kanter, in Kanter, Laurence, and Pia Palladino, eds. Fra Angelico. Exh. cat. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2005., 242–45, no. 44b

Notes

-

Recorded in Seymour, Charles, Jr. Early Italian Paintings in the Yale University Art Gallery. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1970., 159. ↩︎

-

For the Hyde panel, see Christie’s, London, April 8, 1938, lot 66; photograph by A. C. Cooper, London, no. 109509. ↩︎

-

Jarves, James Jackson. Descriptive Catalogue of “Old Masters” Collected by James J. Jarves to Illustrate the History of Painting from A.D. 1200 to the Best Periods of Italian Art. Cambridge, Mass.: H. O. Houghton, 1860., 47, no. 41; and Sturgis, Russell, Jr. Manual of the Jarves Collection of Early Italian Pictures. New Haven: Yale College, 1868., 46. ↩︎

-

Sirén, Osvald. “Trecento Pictures in American Collections—III.” Burlington Magazine 14, no. 71 (February 1909): 325–26., 326, pl. 2, no. 1; and Sirén, Osvald. A Descriptive Catalogue of the Pictures in the Jarves Collection Belonging to Yale University. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1916., 79–80. ↩︎

-

Offner, Richard. Italian Primitives at Yale University: Comments and Revisions. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1927., 5. ↩︎

-

Berenson, Bernard. Italian Pictures of the Renaissance: A List of the Principal Artists and Their Works with an Index of Places. Oxford: Clarendon, 1932., 365; and Berenson, Bernard. Italian Pictures of the Renaissance, A List of the Principal Artists and Their Works with an Index of Places: The Florentine School. 2 vols. London: Phaidon, 1963., 1:68. ↩︎

-

Zeri initially accepted Berenson’s attribution to Domenico di Michelino (Fredericksen, Burton B., and Federico Zeri. Census of Pre-Nineteenth-Century Italian Paintings in North American Public Collections. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1972., 599) but later adopted for this artist the epithet Pseudo-Domenico di Michelino that had been coined in 1948 by Roberto Longhi. See Longhi, Roberto. “Il Maestro della Predella Sherman.” Proporzioni 2 (1948): 161–62., 162; and Federico Zeri, “Major and Minor Italian Artists at Dublin.” Apollo 99, no. 144 (February 1974): 88–103., 92. ↩︎

-

Seymour, Charles, Jr. Early Italian Paintings in the Yale University Art Gallery. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1970., 159, no. 113. Longhi renamed the artist the Master of the Buckingham Palace Madonna in 1953, as reported by Michel Laclotte, in Laclotte, Michel, ed. De Giotto à Bellini: Les primitifs italiens dans les musées de France. Exh. cat. Paris: Éditions des musées nationaux, 1956., 68. ↩︎

-

Salmi, Mario. “Problemi dell’Angelico.” Commentari, n.s., 1 (1950): 75–81, 146–56., 75–81, 146–56; and Collobi Ragghianti, Licia. “Zanobi Strozzi pittore.” Parts 1 and 2. Critica d’arte, 3rd ser., 8, no. 6, fasc. 32 (March 1950): 454–73; 3rd ser., 9, no. 1, fasc. 33 (May 1950): 17–27., 17–27, 454–73. ↩︎

-

Boskovits, Miklós. Un’Adorazione dei Magi e gli inizi dell’Angelico. Bern, Switzerland: Abegg-Stiftung Bern, 1976.; and Boskovits, Miklós. “Appunti sull’Angelico.” Paragone 313 (1976): 30–54., 30–54. ↩︎

-

Inv. no. NG1406, https://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/paintings/zanobi-strozzi-the-annunciation. ↩︎

-

Gordon, Dillian. “Zanobi Strozzi’s ‘Annunciation’ in the National Gallery.” Burlington Magazine 140, no. 1145 (August 1998): 517–24., 517–24. ↩︎

-

Carl Brandon Strehlke, in Kanter, Laurence, Barbara Drake Boehm, Carl Brandon Strehlke, Gaudenz Freuler, Christa C. Mayer Thurman, and Pia Palladino. Painting and Illumination in Early Renaissance Florence, 1300–1450. Exh cat. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1994.; di Lorenzo, Andrea, et al. Omaggio al Beato Angelico: Un dipinto per il Museo Poldi Pezzoli. Exh. cat. Cinisello Balsamo, Milan: Silvana, 2001.; Scudieri, Magnolia, and Giovanna Rasario. Miniatura del ’400 a San Marco: Dalle suggestioni avignonesi all’ambiente dell’Angelico. Exh. cat. Florence: Giunti, 2003.; and Kanter, Laurence, and Pia Palladino, eds. Fra Angelico. Exh. cat. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2005.. Confusion between Angelico and Strozzi, both as miniaturists and panel painters, persists, but the general outlines of their separate careers are now fairly firm. ↩︎

-

Laurence Kanter, in Kanter, Laurence, and Pia Palladino, eds. Fra Angelico. Exh. cat. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2005., 242–45, no. 44b. ↩︎

-

Museo di San Marco, Florence, inv. no. 879. ↩︎

-

The Buckingham panel is part of the Royal Collection, inv. no. RCIN 400039, https://www.rct.uk/collection/400039/the-madonna-of-humility-with-angels. For the Alana Collection panel, see Aldo Galli, in Boskovits, Miklós, ed. Italian Paintings from the 13th to the 15th Century. The Alana Collection 1. Florence: Polistampa, 2009., 209–13; and sale, Christie’s, New York, June 9, 2022, lot 48. The Santa Maria Nuova altarpiece is discussed in detail in Scudieri, Magnolia, and Giovanna Rasario. Miniatura del ’400 a San Marco: Dalle suggestioni avignonesi all’ambiente dell’Angelico. Exh. cat. Florence: Giunti, 2003., 124–44. ↩︎

-

Inv. no. 1890 nn. 8493–94. ↩︎

-

Pope-Hennessy, John. Fra Angelico. 2nd ed. London: Phaidon, 1974., 211. ↩︎

-

Pope-Hennessy, John. Fra Angelico. 2nd ed. London: Phaidon, 1974., 211; and Kanter, in Kanter, Laurence, and Pia Palladino, eds. Fra Angelico. Exh. cat. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2005., 229. ↩︎

-

For Gradual A, see Scudieri, Magnolia, and Giovanna Rasario. Miniatura del ’400 a San Marco: Dalle suggestioni avignonesi all’ambiente dell’Angelico. Exh. cat. Florence: Giunti, 2003., 173–79. ↩︎

-

Pia Palladino, in Medica and Toniolo 2016, 175–77 (with previous bibliography). ↩︎

-

National Gallery, London, inv. no. NG1406, https://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/paintings/zanobi-strozzi-the-annunciation. ↩︎