Albertini collection, Pistoia;1 Sir Charles Townley, England, 1877;2 Sarah Maude Peto Crossley (1847–1938), Burton-Pynsent, Yeovil, Somerset, England;3 Koetser Gallery, New York, May 1939;4 E. and A. Silberman Galleries, New York, 1940; Hannah D. and Louis M. Rabinowitz (1887–1957), Sands Point, Long Island, N.Y., ca. 1944

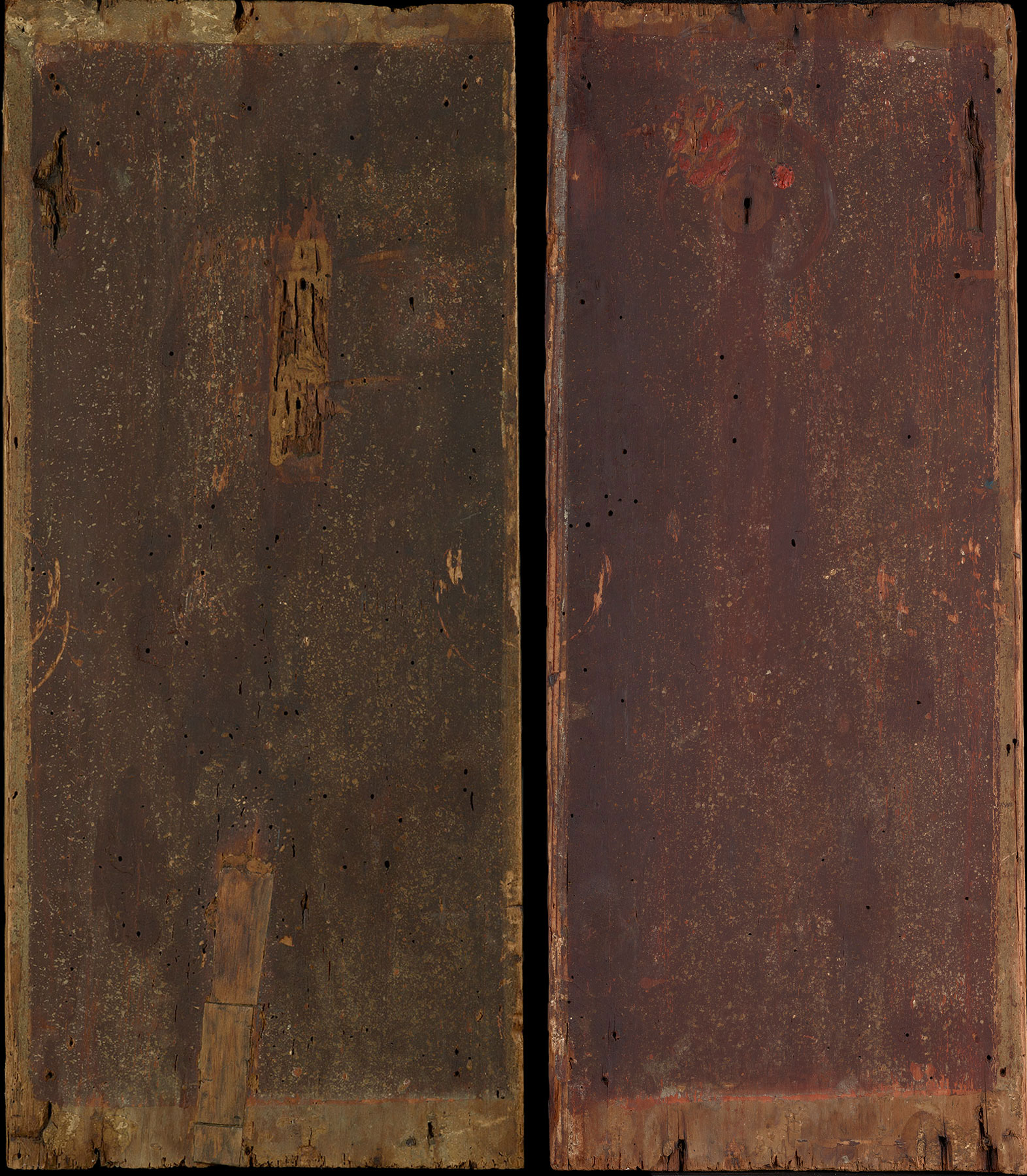

The three fragments (fig. 1), cut from two panels with a vertical wood grain, all retain their original thickness of 1.7 centimeters and remnants of painted porphyry decoration with a white border on their reverses, better preserved in fragment c, the Virgin Annunciate, than in the other two. Fragment a, the Annunciatory Angel, and fragment b, a wedge of gilding, were cut from a single panel and were reconstructed with a plywood inlay in 2000 to an approximation of their original demilunette shape by Mark Aronson; their combined dimensions are now 18.3 by 22.4 centimeters. The back (left) edge of the Angel is slightly beveled away from the picture surface and is likely to be original. The back (right) edge of the Virgin has been trimmed, but a lightly engraved line running the full height of the panel 3 millimeters from its right edge suggests that little or no surface of the image has been lost. Gilding on this panel has been lightly abraded, and oil glazes originally modeling the tooled cloth of honor covering the back of the Virgin’s throne are lost. The paint surface is beautifully preserved. Gilding on the panel with the Angel and on the wedge has been lightly abraded. The paint surface of the Angel is well preserved, but oil glazes covering his wings have been lost, and the purple shadows of his draperies have faded.

Originally two demilunettes that formed the upper section of a pair of tabernacle wings, these panels were cut to geometrically irregular shapes to enable their reconstruction as a single rectangular scene of the Annunciation sometime before they entered the Rabinowitz collection (fig. 2); presumably, they had been rebuilt in this form from at least the time of their appearance in the Towneley collection, if not earlier. Except for an attribution to Fra Filippo Lippi assigned to them by Lionello Venturi5 and under which they were exhibited at the E. and A. Silberman Galleries in 1955, they have always been considered within the circle of painters around Fra Angelico in the second quarter of the fifteenth century. Charles Seymour, Jr., initially called them “Unknown Florentine” but compared them to the Griggs Crucifixion in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (see Fra Angelico, Saint Joseph(?), fig. 1), a painting that has subsequently come to be recognized as an early work by Fra Angelico.6 Rethinking that relationship later, in 1970 Seymour suggested the name of Domenico di Michelino, who at the time was regularly confused with Zanobi Strozzi and adduced as a label for a variety of Angelico-related styles.7 Seymour specifically compared the Yale Annunciation to the predella of the Prado Annunciation altarpiece, another painting now recognized as a masterpiece of Fra Angelico’s early career.8 Federico Zeri listed the Annunciation only as “Florentine school, fifteenth century,” while Flora Clancy followed Seymour’s formula of “Follower of Angelico, ca. 1440.”9 Miklós Boskovits10 was the first to propose attributing the paintings directly to Fra Angelico, suggesting that the Angel and the Virgin might have formed the pinnacles of triptych wings of which another fragment was a Nativity in the Minneapolis Institute of Arts.11 This attribution was followed by Giorgio Bonsanti and the present author.12 The latter, however, rejected an association with the Minneapolis Nativity on the grounds of incompatible dimensions and proposed an alternative reconstruction that was later confirmed by technical evidence.

The relationship of the three fragments to each other and their approximate original dimensions are indicated by the painted decoration of their reverses: a fictive porphyry field with painted white border (fig. 3). The Virgin, which was trimmed at the right and left, currently measures 17.7 centimeters in width but was once at least 20 centimeters wide. The Annunciatory Angel has been more aggressively cropped, but its reconstruction with the triangular section of unpainted gilding—the painted arches on the reverses of the two fragments are continuous—results in a panel 22.4 centimeters wide. These dimensions correspond to those of a pair of tabernacle wings now in the collection of the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, portraying Saints Francis and a bishop saint in the left wing (52.7 × 23.2 cm) and Saints John the Baptist and Dominic in the right wing (53.7 × 21 cm) (fig. 4). The Getty panels have painted reverses (fig. 5) identical to those of the Yale panels, and the painted white margins of the Getty panels trimmed across their upper edges continue along the lower edges of the Yale panels. X-radiographs of the four panels show that the vertical wood grain of their supports is continuous across the two pairs. Judging from the varying widths of the white painted margins in the Getty panels, they, too, have been trimmed somewhat in width, especially along their inner edges, resulting in a total width for the two wings of approximately 46 centimeters, or slightly more, when folded closed. Their total original height is more difficult to estimate, given the cropping of the Yale panels above and a similar loss at the bottoms of the Getty panels. Hinge scars on the reverses of the latter are situated less than 1 centimeter from the lower edge of each, suggesting the loss of as much as 5 centimeters of wood along this edge. An original height for the full tabernacle may be estimated, therefore, as 80 centimeters or perhaps slightly greater. The painted surface of Angelico’s tabernacle in Rotterdam, the Netherlands, which dates only slightly earlier than the Getty and Yale panels, is probably the correct size to have stood between them, but the frame of that painting is original and indicates that it never had folding wings.13

When first proposing the connection between the Getty and Yale panels, the present author suggested a date for them of ca. 1424, based on their relationship to the predella of the high altarpiece from San Domenico in Fiesole and, to a lesser extent, the San Pietro Martire altarpiece, both then thought to date from about that time.14 Persuasive arguments have since been advanced to consider the San Domenico altarpiece as a work possibly begun as early as 1419 and completed by 1421, with its predella among the last of its sections to have been painted.15 The dating of the San Pietro Martire altarpiece is dependent on that of the San Domenico altarpiece and has consequently been advanced to ca. 1421–22. The Getty/Yale triptych must also have been painted in about 1421 or 1422, although Angelico’s chronology over the first decade and a half of his career is based entirely on relative comparisons: precise dating for any work by him prior to 1430 is inferential. More important, however, than pinpointing the year of execution of the triptych is the recognition that it must be exactly contemporary to one of the most beautiful, and puzzling, works ever painted by Fra Angelico, the Virgin and Child with Twelve Angels (fig. 6) in the Städel Museum, Frankfurt. The unusual rectangular format of this panel has frustrated efforts to reconstruct its original function or the type of structure of which it might have formed part. It has never been adduced as a candidate for the center panel of the Getty/Yale triptych due to its smaller dimensions (37.5 × 29.7 cm), but recent technical examination of its support might suggest that a consideration of this possibility is appropriate.

The panel support of the Frankfurt painting has a horizontal grain, which, as Carl Strehlke has observed, is routinely encountered in Tuscan painting of this period in panels that are wider than they are tall.16 He concluded, therefore, that the panel (although not the picture surface, which preserves a barb from its original frame moldings) must have been cropped on the left and right. The amount cropped would have been substantial if the original format of this panel was horizontal: as the panel also preserves evidence of frame moldings trimmed away at top and bottom, its original height would have been at least 40 centimeters, and its width would have been greater than that, very possibly equal to the combined width of the Getty and Yale panels: about 46 centimeters. In such a case, it would be necessary to explain the more than 16 centimeters difference between the overall width of the panel and its painted surface. One possible explanation would be that the painting was embedded in the center of a reliquary tabernacle, and as is typical in many such structures, the reliquary cavities flanking the painted image were created by frame moldings projecting forward of the main panel support.17 This hypothesis could also explain the dowel pegs embedded in the panel at top and bottom, attaching it to a base or painted predella and a tympanum. The latter could have housed further reliquary cavities and, potentially, an image of the blessing God the Father, completing the Annunciation imagery in the hypothetical wings. It may not be coincidental that three of the four reliquaries painted by Fra Angelico for San Marco after 1424 are similar in the width of their painted surfaces to the Frankfurt panel and in the overall dimensions of their frames to the combined dimensions of the Getty/Yale wings.18

In his own reconstruction of the original format of the Frankfurt panel, Strehlke argued for the possibility that it might have served as a sacrament tabernacle at San Domenico, Fiesole, while admitting that it is uncertain what form such a tabernacle might have taken, as they do not become common liturgical fixtures in Florence until after 1450. If it might instead have formed part of a portable reliquary tabernacle, Strehlke’s arguments for a likely provenance from San Domenico are nevertheless compelling. In his discussion of the Getty panels, the present author suggested a tentative identification for the bishop saint in the left wing as Saint Zenobius and, consequently, a possible identification of the original patron as Fra Giovanni di Zanobi Masi.19 Masi was a founding member of the Dominican Observant community at San Domenico in Fiesole in 1419, transferring later to San Marco in Florence where, according to Giuseppe Richa, he commissioned the four reliquary tabernacles from Fra Angelico in or after 1424. Although entirely speculative, it remains possible that the Yale Annunciation, Getty Saints, and Frankfurt Virgin and Child with Twelve Angels are the surviving remains of his initial patronage of Fra Angelico, predating the creation of the four painted reliquaries now divided between the Museo di San Marco and the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston.20 —LK

Published References

Venturi, Lionello. The Rabinowitz Collection. New York: Twin Editions, 1945., 15–16, pl. 8; An Exhibition of Paintings, for the Benefit of the Research Fund of Art and Archaeology, The Spanish Institute, Inc. New York: E. and A. Silberman Galleries, 1955., 15; “Recent Gifts and Purchases: February 22–December 31, 1959.” Yale University Art Gallery Bulletin 26, no. 1 (December 1960): 52–58., 53; Seymour, Charles, Jr. The Rabinowitz Collection of European Paintings. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1961., 18–19, 54; Seymour, Charles, Jr. Early Italian Paintings in the Yale University Art Gallery. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1970., 132–34, no. 91; Fredericksen, Burton B., and Federico Zeri. Census of Pre-Nineteenth-Century Italian Paintings in North American Public Collections. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1972., 601; Flora Clancy, in Seymour, Charles, Jr., et al. Italian Primitives: The Case History of a Collection and Its Conservation. Exh. cat. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1972., 54–55, no. 47, figs. 47a–d; Boskovits, Miklós. Un’Adorazione dei Magi e gli inizi dell’Angelico. Bern, Switzerland: Abegg-Stiftung Bern, 1976., 38, 41, 50n27, 52n41; Boskovits, Miklós. “La fase tarda del Beato Angelico: Una proposta di interpretazione.” Arte cristiana 694 (1983): 11–24., 11–24; Kenney, Elise K., ed. Handbook of the Collections: Yale University Art Gallery. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1992., 134; Bonsanti, Giorgio. Beato Angelico: Catalogo completo. Florence: Octavo, 1998., 115; Kanter, Laurence. “An Annunciation by Fra Angelico.” In Rediscovering Fra Angelico: A Fragmentary History, ed. Clay Dean, 17–39. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 2001., 13–39; Laurence Kanter, in Kanter, Laurence, and Pia Palladino, eds. Fra Angelico. Exh. cat. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2005., 95–98, no. 17

Notes

-

According to dealer’s record. ↩︎

-

According to Seymour, Charles, Jr. Early Italian Paintings in the Yale University Art Gallery. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1970., 134. There is, however, no Sir Charles Townley recorded in the generation that would have been alive in 1877. This may be Colonel Charles Towneley (1803–1876) of Towneley Hall, Burnley, Lancashire, whose grandfather, Charles Towneley (1737–1805), was resident in Florence and Rome from ca. 1765. Colonel Charles Towneley was an avid collector of Roman antiquities—a gallery at the British Museum, London, is named for him—and it may have been he who first owned the Angelico. The family were prominent Catholic landowners in the north of England. ↩︎

-

This identical provenance chain, Albertini—Townley—Crossley, is recorded for the Portrait of a Young Man by Marco Basaiti, sold at Sotheby’s, New York (January 25, 2011, lot 102), and the Portrait of a Lady in Profile attributed to Baldassare d’Este (From Borso to Cesare d’Este: The School of Ferrara, 1450–1628. Exh. cat. London: Matthiesen Fine Art, 1984., 64, no. 6, pl. 6, lent by Wildenstein and Co.). ↩︎

-

According to a photograph in the Richard Offner Photo Archives, Institute of Fine Arts, New York University. ↩︎

-

Venturi, Lionello. The Rabinowitz Collection. New York: Twin Editions, 1945., 15–16, pl. 8. ↩︎

-

Seymour, Charles, Jr. The Rabinowitz Collection of European Paintings. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1961., 18–19, 54. ↩︎

-

Seymour, Charles, Jr. Early Italian Paintings in the Yale University Art Gallery. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1970., 132–34. ↩︎

-

Inv. no. P000015/002, https://www.museodelprado.es/en/the-collection/art-work/scenes-from-the-life-of-the-virgin/7da17107-db99-4819-b73c-f5cb0b26915a. ↩︎

-

Fredericksen, Burton B., and Federico Zeri. Census of Pre-Nineteenth-Century Italian Paintings in North American Public Collections. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1972., 601; and Flora Clancy, in Seymour, Charles, Jr., et al. Italian Primitives: The Case History of a Collection and Its Conservation. Exh. cat. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1972., 54–55, nos. 47a–d. ↩︎

-

Boskovits, Miklós. Un’Adorazione dei Magi e gli inizi dell’Angelico. Bern, Switzerland: Abegg-Stiftung Bern, 1976., 38, 41, 50n27, 52n41; and Boskovits, Miklós. “La fase tarda del Beato Angelico: Una proposta di interpretazione.” Arte cristiana 694 (1983): 11–24., 11–24. ↩︎

-

Inv. no. 68.41.8, https://collections.artsmia.org/art/1680/the-nativity-fra-angelico. ↩︎

-

Bonsanti, Giorgio. Beato Angelico: Catalogo completo. Florence: Octavo, 1998., 115; Kanter, Laurence. “An Annunciation by Fra Angelico.” In Rediscovering Fra Angelico: A Fragmentary History, ed. Clay Dean, 17–39. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 2001., 13–39; and Laurence Kanter, in Kanter, Laurence, and Pia Palladino, eds. Fra Angelico. Exh. cat. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2005., 95–98. ↩︎

-

Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam, the Netherlands, https://www.boijmans.nl/en/collection/artworks/3860/madonna-and-child-with-two-angels. ↩︎

-

Kanter, Laurence. “An Annunciation by Fra Angelico.” In Rediscovering Fra Angelico: A Fragmentary History, ed. Clay Dean, 17–39. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 2001., 13–39. ↩︎

-

See Strehlke, Carl Brandon. Fra Angelico and the Rise of the Florentine Renaissance. Exh. cat. Madrid: Museo Nacional del Prado, 2019., 116–29. ↩︎

-

Strehlke, Carl Brandon. Fra Angelico and the Rise of the Florentine Renaissance. Exh. cat. Madrid: Museo Nacional del Prado, 2019., 130–32. ↩︎

-

See Williamson, Beth. “Fra Angelico and Siena: Contextualizing the Painted Reliquary.” Fra Angelico: Heaven on Earth, ed. Nathaniel Silver, 41–55. Exh. cat. Boston: Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, 2018., 41–55. Although several of the Sienese examples cited here are constructed in the fashion outlined, none of them includes folding wings. Evidence is incomplete as to whether any, such as the Madonna of Humility by Andrea di Bartolo in the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. (inv. no. 1939.1.20.a, https://www.nga.gov/collection/art-object-page.160.html), might once have done so. ↩︎

-

See Nathaniel Silver, in Silver, Nathaniel. “Fra Angelico, Giovanni Masi, and the Reliquaries for Santa Maria Novella.” In Fra Angelico: Heaven on Earth, ed. Nathaniel Silver, 32–39. Exh. cat. Boston: Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, 2018., 150–79, nos. 1–4. The frame on the first of the reliquaries, the so-called Madonna della Stella, is the only original frame of the four, but all three of the reliquaries still in San Marco retain sufficient fragments of their original structure to estimate their overall dimensions. The chronology of these four works proposed by Silver is based on iconographic, not stylistic, considerations. An alternative proposal was formulated by the present author in Kanter, Laurence, and Pia Palladino, eds. Fra Angelico. Exh. cat. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2005., 147–51; and with slight variations in Kanter, Laurence. Review of Fra Angelico, Boston. Burlington Magazine 160, no. 1382 (May 2018): 408–10., 408–10. ↩︎

-

Laurence Kanter, in Kanter, Laurence, and Pia Palladino, eds. Fra Angelico. Exh. cat. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2005., 97–98, no. 17. ↩︎

-

Museo di San Marco, Florence, inv. no. 1918 nn. 274–76; and Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston, inv. no. P15W34, https://www.gardnermuseum.org/experience/collection/11697. ↩︎