Cavalliere Masi, Capánnoli, near Pontedera; Achillito Chiesa (1881–1951), Milan; Vicomte Bernard d’Hendecourt (1874–1928), Paris, by 1921; sale, Sotheby’s, London, May 8, 1929, lot 112; Maitland Fuller Griggs (1872–1943), New York, 1929

The panel support, of a horizontal grain, comprises a single plank and retains its original thickness of 3.5 centimeters. Original engaged moldings are preserved at top and bottom, but the panel has been cut at left and right. A slight barb along the edge of the picture surface and beveled cuts at the ends of the engaged moldings imply that engaged pilaster bases once enclosed both lateral edges. Three cross-grain battens, each approximately 7 centimeters wide, were once affixed to the reverse. Three nails, aligned vertically, that secured the central batten are still embedded in the panel beneath the strip of punched and gilt decoration that divides the two scenes. Discolorations of the wood and glue residue about 3 centimeters wide at either end on the reverse indicate that half a batten is missing at both edges. Square cavities were cut into the panel to receive the nails driven in, front to back; the heads were recessed within the cavities and then covered with wood plugs, linen, and gesso. Three half-cavities are now exposed at both edges: these are missing their plugs but were never covered with linen or gesso, as they were concealed by the applied pilaster bases.

The gilded and painted surfaces were heavily abraded in a cleaning of 1960–61, leaving large areas of exposed bolus, gesso, and wood substrate visible in both frame moldings and exposing a circular area of total loss near the top edge of the central dividing strip. It is possible that a shield with a coat of arms or some other freestanding decorative device was once affixed to the panel at this point. The landscape in the right scene was harshly scrubbed, removing dark tones throughout the rock forms and reducing the faces of the three figures standing at the left to underpaint. Drapery forms and colors are much better preserved. The green of the water in the scene at left was treated with equal severity, breaking the transitions from light to dark progressing from the bottom (front) to top (back) of the water and erasing several painted fish that were once visible there; the latter can still be detected with infrared reflectography. Glazes that once defined the angel’s wings are missing, as are most of the drawn features in the faces of all the figures. The church facade at the far left is relatively intact.

This painting portrays two scenes rarely encountered in Italian art. At the right is a miracle associated with the first apparition of Saint Michael the Archangel, as told in the fourteenth-century compendium of the lives of the saints, the Golden Legend, written by Jacobus de Voragine. A rich man, who “had sheep and cattle beyond counting,” grazed his herds on the flanks of Mount Gargano, in Apulia. It happened one day that

one bull separated himself from the rest and climbed to the top of the mountain. When . . . the bull’s absence was discovered, the landowner mustered a band of his people to track it up the mountain trails, and they finally found the animal standing in the mouth of a cave at the top. The owner, annoyed at the bull for having wandered off alone, aimed a poisoned arrow at it, but the arrow came back, as if turned about by the wind, and struck the one who had launched it. This dismayed the townsmen, and they went to the bishop and asked him what he thought of the strange occurrence. Saint Michael appeared to the bishop and said: “Know that it was by my will that the man was struck by his arrow. I am the archangel Michael, and I have chosen to dwell in that place on earth and to keep it safe.” . . . The bishop and the townspeople formed a procession and went to the cave, but, not presuming to enter, stood around the entrance, praying.1

The second apparition of Saint Michael, portrayed at the left in the Yale panel, occurred at Mont Saint Michel on the Normandy coast. This mountain on which Saint Michael ordered his church to be built, according to de Voragine,

is surrounded on all sides by the ocean, but twice on the saint’s feast day [October 16] a path is opened to allow the people to walk over. One such day, when a large throng was crossing to the church, it happened that a woman who was pregnant and close to her time went with them. Then the tide came in with a rush, and the crowd, terrified, made for the shore, but the pregnant woman could not move fast enough and was caught by the waves. The archangel Michael, however, kept her unharmed, in such a way that she brought forth her son in the welter of the sea and nursed him there in her arms. Then the waters again opened a path for her, and she walked joyfully ashore with her child.2

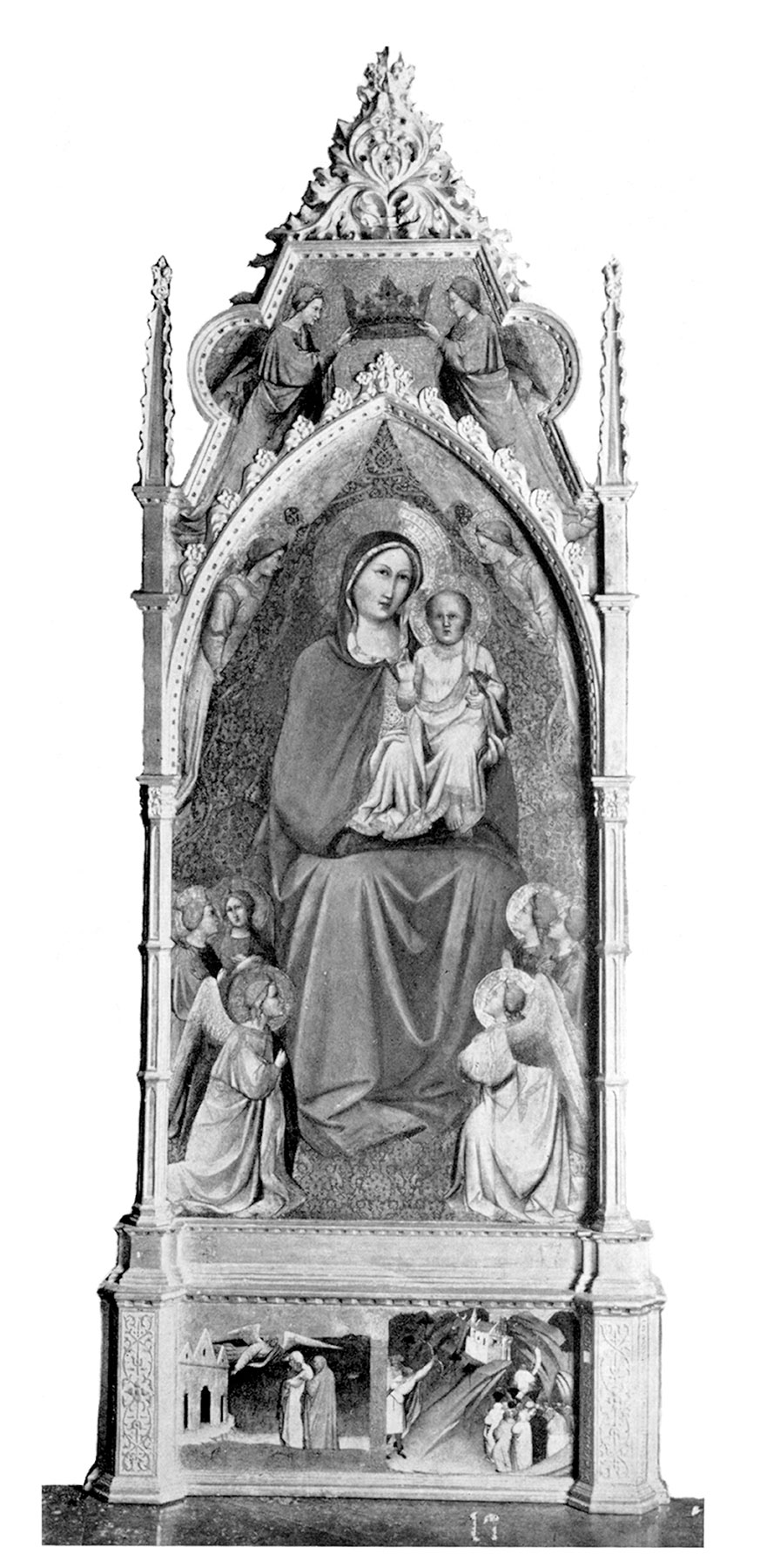

When it was part of the Masi collection at Capánnoli, the predella now at Yale was built into a large neo-Gothic frame beneath a Virgin and Child Enthroned with Eight Angels by Agnolo Gaddi. Photographs of it in this configuration (fig. 1) appear in publications well into the 1930s, but the two paintings had been separated either by the time the larger panel reached the Achillito Chiesa collection in Milan, sometime before 1921, or while they were in the Chiesa collection. When Tancred Borenius published the predella, it had been sold to the Vicomte Bernard d’Hendecourt in Paris;3 the Virgin and Child remained in the Chiesa collection until 1926, later passing into the collection of Alessandro Contini Bonacossi.4 It is now exhibited as part of the Contini Bonacossi bequest at the Gallerie degli Uffizi, Florence.5 The subsequent critical history of the Yale panel was entirely predicated on this association, even though it was evidently a nineteenth-century pastiche. Scholars limited themselves to opinions of whether the panel was by Agnolo Gaddi himself,6 by a follower then known alternatively as the “Compagno d’Agnolo” or Gherardo Starnina,7 or by an unknown Florentine contemporary of Agnolo Gaddi.8

Based on its having been found together with the Contini Virgin and Child, Hans Gronau proposed a reconstruction of the original altarpiece of which the two panels would have formed part, which he supposed was dedicated to Saint Michael the Archangel.9 His reconstruction included two further predella panels with scenes from the legend of Saint Michael—another panel at Yale, now recognized to be the work of Lippo d’Andrea (see Lippo d’Andrea, Two Scenes from the Legend of Saint Michael), and one at the Pinacoteca Vaticana, Vatican City.10 He identified one of two hypothetical lateral panels from the main tier of the altarpiece in a fragment showing half-length figures of Saints Julian, James, and Michael, also at Yale, painted either by Agnolo Gaddi or Lorenzo Monaco (see Agnolo Gaddi or Lorenzo Monaco, Saints Julian, James, and Michael). Bruce Cole rejected this reconstruction on the grounds that another proposal had been advanced for identifying the lateral panels originally belonging to the Contini Virgin and Child, showing full-length standing figures of Saints Benedict (sometimes said to be John Gualbert), Peter, John the Baptist, and Minias, now framed together with the Contini Madonna at the Uffizi (fig. 2).11 Miklós Boskovits also rejected Gronau’s reconstruction on the basis of the wide stylistic disparity among the panels, no two of which appear to be by the same artist.12 He continued, however, to maintain a connection between the Contini Virgin and Child and the Yale predella and therefore also rejected the proposed association of the former with the standing saints now joined to it at the Uffizi.13 Following these two negative judgments, and the disastrous cleaning to which the Yale predella was subjected in 1960–61, no further research on the problem appeared in print until the panel was loaned to the Museo del Prado, Madrid, in 2019. On that occasion, the catalogue entry by Carl Strehlke summarized a hypothesis for attribution and reconstruction developed over the preceding three years by Irma Passeri and the present author.14

There is no stylistic basis for associating the Yale predella with the work of Agnolo Gaddi that could justify its fortuitous connection to the Contini Virgin and Child. Gaddi’s preference for full-face or profile heads, his tendency to arrange narratives either parallel to the picture plane or along carefully plotted orthogonals, and his utter disregard for diminishing the scale of his figures to reflect their distance in space behind the picture plane are all incompatible with the composition of the right-hand scene of the Yale panel. The crowd of figures moving back up the hill path in this scene, defining an elegant S curve, with a great number of bodies and heads seen from behind, demonstrates a command of spatial illusion not to be found in the work of any fourteenth-century Florentine painter. The fully modeled volumes of the figures, with persuasively accurate contrasts of highlight and shadow, and the highly naturalistic details of dress, ornament, and architecture in both scenes of the Yale panel are not encountered at this level of sophistication until the second decade of the fifteenth century—specifically in paintings attributed to the early career of Fra Angelico. The drawing of the faces in the crowd on the right, revealed through thinning layers of paint, resembles that in several drawings attributed to the young Fra Angelico.15 The church surrounded by a fortified wall and tower behind them may be a record of the actual shrine of Saint Michael on Monte Gargano as it then appeared, or it may be an invention of Angelico’s; the same building, seen from the opposite side, appears in an illustrated pilgrimage roll dated 1417 that was painted, in part, by him (fig. 3).16 In both instances, the structural integrity of the building reveals Angelico’s optical, empirical approach to rendering architecture, as opposed to the emblematic structures painted by his predecessors and contemporaries. Also typical of Angelico’s practice—throughout his career—are such seemingly inconsequential devices in the Yale panel as the horizontal break in drapery folds where they rest upon shoes, a means for the artist to indicate that a figure is bending forward, and the gratuitous curling folds at the hems of garments that reveal a brief glimpse of the cloth lining, painted in a complementary color. The tender gestures of the mother protecting her baby by wrapping him in her cloak and of the Archangel leading her ashore by gently cradling the back of her head are uniquely characteristic of Angelico’s narrative sensibilities.

The appearance of punch tool impressions from a halo beneath the paint surface of each scene in the Yale panel—now distinctly visible only in raking light, beneath the figure of the newborn child in the left scene and beneath the archer’s forward hand in the right scene—coupled with irregularities in the gesso preparatory layer led to the realization that both of the scenes of Saint Michael were painted atop earlier scenes that bore no relation to them. Scraping marks in the gesso, tapering and becoming shallower as they approach the edges of the painted field, indicate that these earlier scenes had been scraped away from the center outward, taking pains to preserve the gilded frame moldings, the decorative gold band dividing the two scenes, and portions of the gilt “sky” in the left scene, on which fragmentary incised crenellated walls or towers indicate that it had once been bordered by a landscape of hills and architecture. This, in turn, prompted the recognition that the alternative architectural forms visible along the left edge of the left scene are a palimpsest rather than a pentimento. As buildings in this configuration seem to have no role in the Miracle at Mont Saint Michel, and as no figure requiring a halo is involved in the narrative of the Miracle of the Bull on Mount Gargano, it is necessary to conclude that the original scenes were altered to change their subjects completely rather than merely to refine their compositions. Physical clues are insufficient to discern the subjects of the original effaced scenes, but a series of documents culminating in a payment to Fra Angelico in February 1418—the earliest-known documents referring to a painting by him—provides a plausible hypothesis. On August 17, 1412, the painter Ambrogio di Baldese accepted a commission to produce an altarpiece for the chapel of San Giovanni Decollato (Saint John Beheaded) in the church of Santo Stefano al Ponte, Florence. The chapel had been endowed by a bequest from Giovanni di Alamanno Gherardini over thirty years earlier, but the commission for its altarpiece was placed only belatedly by the Captains of Orsanmichele—a charitable institution dedicated to Saint Michael the Archangel and charged with the testamentary execution of Florentine estates. Payments to Ambrogio di Baldese for work on this altarpiece are registered between 1415 and 1417, with final payment (“per residuo solutionis picture dicte cappelle”) disbursed on April 6 of the latter year.17 Less than nine months later, on January 28, 1418, Guido di Pietro, the future Fra Angelico, was paid five florins for further unspecified work on the altarpiece (“pro parte solutionis tabule altaris”)—work that he had finished by February 15, when he received an additional seven florins as final payment (“pro residuo solutionis tabule altaris dicte cappelle quam fecit”).18

Sonia Chiodo’s discovery of the remains of the Saint John the Baptist altarpiece originally painted for the Gherardini Chapel in Santo Stefano al Ponte (fig. 4) has proven to be the first tangible evidence for association of the historical Ambrogio di Baldese—a painter otherwise known from numerous documents but no works of art—with a body of painted work: that of the artist formerly known as the Master of the Straus Madonna.19 Since no trace of Angelico’s intervention could be detected within that altarpiece, however, her proposal for this identification was not universally or even widely accepted. Boasting a sixteenth-century provenance from the Gherardini family and including among its crowd of figures the three saints most intimately tied to the commission—Saint Stephen, patron of the church, in the position of honor at the Virgin’s right; Saint John the Baptist, patron of the chapel and name-saint of the donor; and the rarely portrayed Saint Michael, patron of the Confraternity of Orsanmichele—the association of the altarpiece with the document seems incontestable. The objection that Angelico’s style at any period of his career bears no relationship to that of the Straus Master/Ambrogio di Baldese is rendered moot by the payment to Ambrogio di Baldese in April 1417 specifying that it is final, precluding any necessity to look for a professional connection between him and Angelico. It is more productive to speculate that Angelico was paid in January and February of the following year to change Ambrogio di Baldese’s painting, possibly to make it more fitting to the patrons who oversaw its execution: the Captains of Orsanmichele. As their patron, Saint Michael the Archangel, appears only inconspicuously among the saints in the main tier of the altarpiece, it is likely that Angelico was asked by them to change two predella scenes—possibly originally commemorating either Saint Stephen or Saint John the Baptist, or both—to episodes from the legend of Saint Michael. The width of each scene in the Yale predella (40.3 cm on the left, 39.8 cm on the right) is to within one centimeter the same as the width of each of the lateral panels in the altarpiece discovered by Chiodo. Whether Angelico might have been asked to alter two further scenes in the other half of the predella or its central scene must remain an open question, pending the discovery of suitable candidates attributable either to his hand or to the Master of the Straus Madonna/Ambrogio di Baldese. —LK

Published References

Borenius, Tancred. “An Unpublished Florentine Predella.” Burlington Magazine 39 (1921): 154., 154; van Marle, Raimond. The Development of the Italian Schools of Painting. Vol. 3. The Hague: M. Nijhoff, 1924., 573–74n2; Sotheby’s, London. Catalogue of the Very Choice and Valuable Collections of the Vicomte Bernard D’Hendecourt. Sale cat. May 8–10, 1929., 16, lot 112, fig. 112; Wulff-Berlin, Oskar. “Nachlese zur Starnina-Frage.” In Italienische Studien: Paul Schubring zum 60. Geburtstag gewidmet, 156–90. Leipzig, Germany: K. W. Hiersemann, 1929., 172–73, 189, fig. 7; Exhibition of Italian Primitive Paintings, Selected from the Collection of Maitland F. Griggs. Exh. cat. New York: Century Association, 1930., no. 13; Berenson, Bernard. Italian Pictures of the Renaissance: A List of the Principal Artists and Their Works with an Index of Places. Oxford: Clarendon, 1932., 242; Salvini, Roberto. “Per la cronologia e per il catalogo di un discepolo di Agnolo Gaddi.” Bollettino d’arte 29 (December 1935): 279–94., 293; Comstock, Helen. “The Yale Collection of Italian Paintings.” Connoisseur 118 (September 1946): 45–52., 47–48, no. 3; “Picture Book Number One: Italian Painting,” special issue, Bulletin of the Associates in Fine Arts at Yale University 15, nos. 1–3 (October 1946): n.p., fig. 6; Gronau, Hans D. “A Dispersed Florentine Altarpiece and Its Possible Origin.” Proporzioni 3 (1950): 41–47., 41–47, pl. 23/fig. 1, pl. 25/fig. 3, pl. 27/fig. 7; Berenson, Bernard. Italian Pictures of the Renaissance, A List of the Principal Artists and Their Works with an Index of Places: The Florentine School. 2 vols. London: Phaidon, 1963., 1:68, pl. 336; Seymour, Charles, Jr. Early Italian Paintings in the Yale University Art Gallery. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1970., 38–39, 41, no. 23; Fredericksen, Burton B., and Federico Zeri. Census of Pre-Nineteenth-Century Italian Paintings in North American Public Collections. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1972., 76, 600; Boskovits, Miklós. Pittura fiorentina alla vigilia del Rinascimento, 1370–1400. Florence: Edam, 1975., 298, 301; Cole, Bruce. Agnolo Gaddi. Oxford: Clarendon, 1977., 72, 76; Volbach, Wolfgang Fritz. Catalogo della Pinacoteca Vaticana. Vol. 2, Il trecento: Firenze e Siena. Vatican City: Libreria Editrice Vaticana, 1987., 39–40; Johannes Roll, in Duston, Allen, and Arnold Nesselrath, eds. Angels from the Vatican: The Invisible Made Visible. Alexandria, Va.: Art Services International, 1998., 234–35; Carl Brandon Strehlke, in Strehlke, Carl Brandon. Fra Angelico and the Rise of the Florentine Renaissance. Exh. cat. Madrid: Museo Nacional del Prado, 2019., 98–99, no. 10

Notes

-

de Voragine, Jacobus. The Golden Legend. Trans. William Granger Ryan. 2 vols. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1993., 2:201–2. ↩︎

-

de Voragine, Jacobus. The Golden Legend. Trans. William Granger Ryan. 2 vols. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1993., 2:202. ↩︎

-

Borenius, Tancred. “An Unpublished Florentine Predella.” Burlington Magazine 39 (1921): 154., 154. ↩︎

-

American Art Association, New York. The Collection of Achillito Chiesa. Vol. 2. April 16, 1926., no. 52. ↩︎

-

Giovanna Ragionieri, in Caneva, Caterina, Enrico Colle, Antonio Paolucci, and Anna Maria Papi, eds. La collezione Contini Bonacossi nelle Gallerie degli Uffizi. Florence: Giunti, 2018., 70. ↩︎

-

Salvini, Roberto. “Per la cronologia e per il catalogo di un discepolo di Agnolo Gaddi.” Bollettino d’arte 29 (December 1935): 279–94., 293; Comstock, Helen. “The Yale Collection of Italian Paintings.” Connoisseur 118 (September 1946): 45–52., 47–48, no. 3; Gronau, Hans D. “A Dispersed Florentine Altarpiece and Its Possible Origin.” Proporzioni 3 (1950): 41–47., 41–47, pl. 23/fig. 1, pl. 25/fig. 3, pl. 27/fig. 7; Berenson, Bernard. Italian Pictures of the Renaissance, A List of the Principal Artists and Their Works with an Index of Places: The Florentine School. 2 vols. London: Phaidon, 1963., 1:68, pl. 336; Seymour, Charles, Jr. Early Italian Paintings in the Yale University Art Gallery. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1970., 38–41, no. 23, fig. 23; Fredericksen, Burton B., and Federico Zeri. Census of Pre-Nineteenth-Century Italian Paintings in North American Public Collections. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1972., 76, 600; and Boskovits, Miklós. Pittura fiorentina alla vigilia del Rinascimento, 1370–1400. Florence: Edam, 1975., 298, 301. ↩︎

-

Borenius, Tancred. “An Unpublished Florentine Predella.” Burlington Magazine 39 (1921): 154., 154; van Marle, Raimond. The Development of the Italian Schools of Painting. Vol. 3. The Hague: M. Nijhoff, 1924., 573–74n2; and Wulff-Berlin, Oskar. “Nachlese zur Starnina-Frage.” In Italienische Studien: Paul Schubring zum 60. Geburtstag gewidmet, 156–90. Leipzig, Germany: K. W. Hiersemann, 1929., 172–73, 189, fig. 7. ↩︎

-

Cole, Bruce. Agnolo Gaddi. Oxford: Clarendon, 1977., 72, 76. ↩︎

-

Gronau, Hans D. “A Dispersed Florentine Altarpiece and Its Possible Origin.” Proporzioni 3 (1950): 41–47., 42. ↩︎

-

Inv. no. 528. ↩︎

-

Cole, Bruce. Agnolo Gaddi. Oxford: Clarendon, 1977., 76. ↩︎

-

Boskovits, Miklós. Pittura fiorentina alla vigilia del Rinascimento, 1370–1400. Florence: Edam, 1975., 298, 301. ↩︎

-

Boskovits and Gaudenz Freuler prefer to link the Uffizi saints with a Virgin and Child Enthroned formerly in the Heinz Kisters Collection, Kreuzlingen (sold at Sotheby’s, New York, February 1, 2018, lot 3). The Kisters Virgin and Child is an early work by Agnolo Gaddi, probably painted in the 1370s, while the Uffizi saints, which do seem compatible with the Contini Virgin and Child, are mature works from ca. 1390. See Freuler, Gaudenz. “Manifestatori delle cose miracolose”: Arte italiana del ’300 e ’400 da collezioni in Svizzera e nel Liechtenstein. Exh. cat. Lugano-Castagnola, Switzerland: Fondazione Thyssen-Bornemisza, 1991., 203–5, nos. 76–77; and Sotheby’s, New York. Master Paintings Evening Sale. Sale cat. February 1, 2018., lot 3. ↩︎

-

Carl Brandon Strehlke, in Strehlke, Carl Brandon. Fra Angelico and the Rise of the Florentine Renaissance. Exh. cat. Madrid: Museo Nacional del Prado, 2019., 98–99, no. 10. ↩︎

-

See Laurence Kanter, in Kanter, Laurence, and Pia Palladino, eds. Fra Angelico. Exh. cat. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2005., 13–19; and Pia Palladino, in Kanter, Laurence, and Pia Palladino, eds. Fra Angelico. Exh. cat. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2005., 40–47, nos. 5a–e. ↩︎

-

See Pia Palladino, in Kanter, Laurence, and Pia Palladino, eds. Fra Angelico. Exh. cat. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2005., 42. ↩︎

-

Chiodo, Sonia. “Pittori attivi in Santo Stefano al Ponte a Firenze e un’ipotesi per l’identificazione del Maestro della Madonna Straus.” Paragone 577 (1998): 48–79., 48–77, esp. 68. ↩︎

-

Chiodo, Sonia. “Pittori attivi in Santo Stefano al Ponte a Firenze e un’ipotesi per l’identificazione del Maestro della Madonna Straus.” Paragone 577 (1998): 48–79., 69. These documents were first published, in less complete form, in Cohn, Werner. “Nuovi documenti per il B. Angelico.” Memorie domenicane 73, n.s. 32 (1956): 218–20., 218–20. ↩︎

-

For a thorough summary of the extensive literature concerning the Master of the Straus Madonna, see Alice Chiostrini, in Hollberg, Cecilie, Angelo Tartuferi, and Daniela Parenti, eds. Cataloghi della Galleria dell’Accademia di Firenze: Dipinti. Vol. 3, Il tardogotico. Florence: Giunti, 2020., 123–24. Documents for Ambrogio di Baldese, who enrolled in the Arte dei Medici e Speziali in 1372 and who died in 1429, can be found in Colnaghi, Dominic E. Colnaghi’s Dictionary of Florentine Painters: From the 13th to the 17th Centuries. Florence: Archivi Colnaghi Firenze, 1986., 13–14. It has been objected (see Alice Chiostrini, in Chiostrini, Alice, and Maria Maugeri, eds. Una sguardo sul Maestro della Madonna Straus: A margine del restauro del Polittico di Citille. Exh. cat. Florence: Polistampa, 2023., 78–83) that the cults of three of the bishop saints included in the Greve altarpiece—Eufrosino, Giusto, and Donato—are localized to the Chianti, and therefore that this painting was never intended for Santo Stefano al Ponte. The objection is invalid. According to Cecilia Frosinini (as kindly communicated to the author by Carl Strehlke in a message of May 22, 2024), the conservator’s report for the altarpiece establishes that the inscription across the base of each bishop’s miter is a later addition of possibly the seventeenth century. Presumably these inscriptions were added to adapt the painting’s iconography to a new context when it was moved out of Santo Stefano. ↩︎