on book, EGO SUM LU / X MUNDI / ET VIA VE / RITAS ET / VITA QU / I SEGUI / TUR ME / NON AB / ITANT I[N] / TENEB[RIS]

Achillito Chiesa (1881–1951), Milan, 1924; art market, Florence; Maitland Fuller Griggs (1872–1943), New York, ca. 1928

The panel, of a vertical grain and 3.3 centimeters thick, was cut across the lower corners and along the bottom edge to create its present pentagonal shape. Modern dowel pegs were inserted into the new bottom and lower-right edges; the lower-left edge is completely covered by a putty fill. The frame moldings engaged along the upper-left and -right edges are old and probably original but have been stripped of any surface decoration or tone. Remnants of discolored bolus along the innermost molding of the frame suggest that it may once have been silvered, as was the semicircular raised molding beneath the figure of Christ. A 2- to 2.5-centimeter strip of exposed wood along the lower-left and -right edges accommodated a modern continuation of the frame moldings, now missing. The gilding and paint surface have been lightly and evenly abraded but are largely preserved intact. A loss in the gold ground just above Christ’s right shoulder has been releafed, as have minor repairs to the gold along the edge of the frame moldings. Five long scratches through Christ’s face have not resulted in significant paint loss. A dull synthetic varnish blunts the color range of the palette and masks the possibility that the gold ground has been reinforced by the addition of a thin layer of modern leaf over the original gilding.

This small image, unanimously attributed to Martino di Bartolomeo, was probably excised from the pinnacle of a hitherto unidentified gabled altarpiece comparable to the artist’s triptych in the National Gallery, Washington, D.C. (fig. 1). As in that work, the half-length figure of Christ, who holds a book open to the words from the Gospel of Saint John (John 8:12 and John 14:6), probably surmounted a central compartment with the Virgin and Child. At an unknown date, the Redeemer was cut from the main panel and along the original corners, resulting in the present pentagonal shape. The remains of a curved molding and punching below the bust of Christ, along with possible traces of pastiglia decoration in the corners at the base of the panel, indicate where the figure, following the example in Washington, was separated from the Virgin and Child below it.

The Yale fragment was first published by F. Mason Perkins in his fundamental 1924 study dedicated to the artist. In that work, the author described “a small tablet with a half-length figure of Christ—in the best manner of the artist—in the collection of Sig. Chiesa in Milan.”1 By 1928, the panel was on the art market in Florence, where it was acquired by Maitland Griggs.2 The attribution to Martino di Bartolomeo, reiterated by Bernard Berenson and Millard Meiss,3 has remained uncontested in all subsequent, if scant, references to the work.

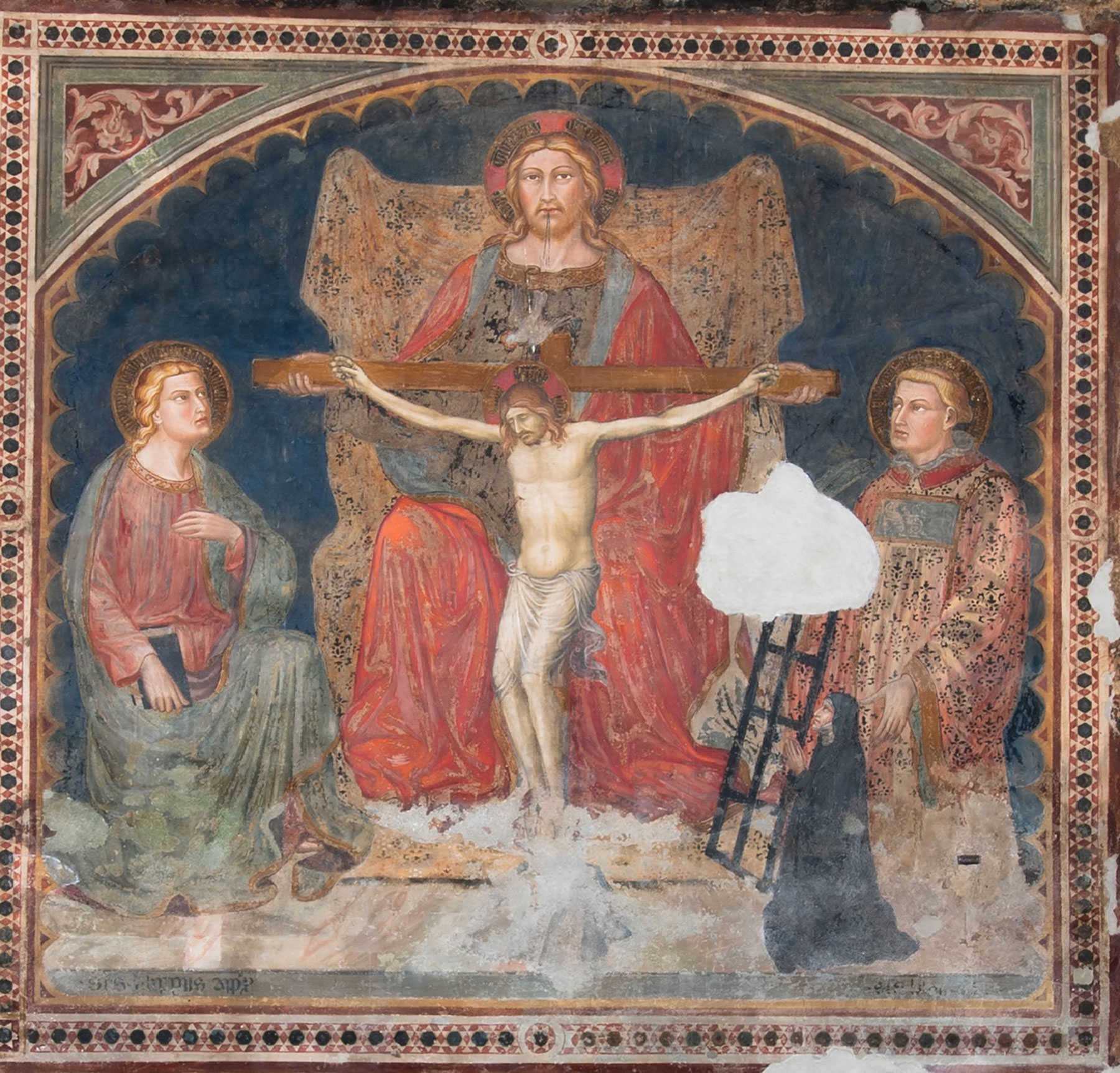

Remarkable for its virtually intact state of preservation, the Yale Blessing Redeemer is typical of the artist’s mature production following his return to Siena in 1405, when the hard, coarser approach of his Pisan works was gradually replaced by a softer, more graceful idiom influenced by the work of Taddeo di Bartolo and other Sienese contemporaries. While Charles Seymour, Jr., dated the painting around 1410, Carol Montfort Molten placed it, less specifically, into a broad category of images executed “after 1410” but convincingly highlighted its similarities to the head of the young Christ in Martino’s fresco of the Holy Trinity in the hospital of Santa Maria della Scala, Siena (Sala Marcacci) (fig. 2).4

A precise terminus post quem for the Yale Redeemer can be established by a comparison with Martino’s four saints in the Pinacoteca Nazionale, Siena (fig. 3), generally regarded as fragments of a polyptych that had at its center a Virgin and Child, signed and dated 1408, formerly in the Bonichi collection, Asciano (later Fossati Bellani collection, Milan).5 As noted by scholars, this work provides the first preview of the new, essentially Sienese figurative vocabulary that would characterize Martino’s production into the next decade. The elegant, serene features of the Pincoteca Saint James are closely related to those of the Yale panel, which shares the same rounded forms and delicate modeling of the features and individual strands of hair and beard.

The looser handling of the contours in the present work, however, suggests a still-further stage in the evolution of the artist’s style, toward a livelier approach that is also discernible in the Trinity fresco in Santa Maria della Scala, appropriately singled out for comparison by Molten. Although there are no records for that commission, circumstantial evidence suggests that the execution of the fresco possibly coincided with Martino’s earliest documented activity for the hospital, in both an administrative and a professional capacity, at the beginning of the second decade.6 Most recently, Gabriele Fattorini proposed a date for the Trinity “toward the second decade of the Quattrocento.”7 A date for the Yale Redeemer in the same moment of the artist’s career, around 1410, seems therefore quite plausible. Both works clearly precede the execution of the Washington triptych, which marks a subsequent phase in the artist’s development, less influenced by the models of Taddeo di Bartolo.8 —PP

Published References

Perkins, F. Mason. “Su alcune pitture di Martino di Bartolomeo.” Rassegna d’arte senese 17 (1924): 5–12., 12; Berenson, Bernard. Italian Pictures of the Renaissance: A List of the Principal Artists and Their Works with an Index of Places. Oxford: Clarendon, 1932., 676; Berenson, Bernard. Italian Pictures of the Renaissance, A List of the Principal Artists and Their Works with an Index of Places: Central Italian and North Italian Schools. 3 vols. London: Phaidon, 1968., 1:246; Seymour, Charles, Jr. Early Italian Paintings in the Yale University Art Gallery. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1970., 82–83, 311, no. 56; Fredericksen, Burton B., and Federico Zeri. Census of Pre-Nineteenth-Century Italian Paintings in North American Public Collections. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1972., 122, 600; Montfort Molten, Carol. “The Sienese Painter Martino di Bartolomeo.” Ph.D. diss., Indiana University, 1992., 102–3, 189, no. 35

Notes

-

Perkins, F. Mason. “Su alcune pitture di Martino di Bartolomeo.” Rassegna d’arte senese 17 (1924): 5–12., 12. ↩︎

-

According to the provenance recorded on the back of a photograph in the Frick Art Reference Library, New York, inv. no. 17507, which cites the source as: “Information obtained from Mr. Griggs, May 12, 1932.” Carol Montfort Molten interpreted Raimond van Marle’s 1925 description of a “half-length figure of the Lord” in the Griggs collection as a reference to the present panel. See van Marle, Raimond. The Development of the Italian Schools of Painting. Vol. 5. The Hague: M. Nijhoff, 1925., 478; and Montfort Molten, Carol. “The Sienese Painter Martino di Bartolomeo.” Ph.D. diss., Indiana University, 1992., 102–3, 189, no. 35. It is more than likely, however, that the painting cited by van Marle was the half-length Blessing Redeemer by Taddeo di Bartolo also in the collection of the Yale University Art Gallery, which was already in the Griggs collection by 1924. ↩︎

-

Berenson, Bernard. Italian Pictures of the Renaissance: A List of the Principal Artists and Their Works with an Index of Places. Oxford: Clarendon, 1932., 676; and Millard Meiss, verbal opinion, 1933, recorded in the Frick Art Reference Library, New York. ↩︎

-

Seymour, Charles, Jr. Early Italian Paintings in the Yale University Art Gallery. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1970., 82–83, no. 56; and Montfort Molten, Carol. “The Sienese Painter Martino di Bartolomeo.” Ph.D. diss., Indiana University, 1992., 102–3, 189, no. 35. ↩︎

-

A prerestoration image of the Virgin and Child was first published in Perkins, F. Mason. “Su alcune pitture di Martino di Bartolomeo.” Rassegna d’arte senese 17 (1924): 5–12., 9. The panel was related to the Pinacoteca saints by Luciano Berti; see Berti, Luciano. “Note brevi su inediti toscani: Paolo di Stefano Badaloni detto Paolo Schiavo (c. 1397–Pisa 1478).” Bollettino d’arte 37, no. 3 (1952): 256–58., 257. For a postrestoration photograph, see Tartuferi, Angelo. “Trecento lucchese: La pittura a Lucca prima di Spinello Aretino.” In Sumptuosa tabula picta: Pittori a Lucca tra gotico e Rinascimento, ed. Maria Teresa Filieri, 42–63. Exh. cat. Florence: Sillabe, 1998., 57, fig. 43. ↩︎

-

Ettore Romagnoli cites Martino’s appointments, in 1410 and 1412, to the office of camarlingo (treasurer) for the Confraternity of the Blessed Virgin Mary under the vaults of the hospital and notes that the artist was commissioned to paint a Last Judgment, now lost, for that organization, to fulfill a 1372 bequest; see Romagnoli, Ettore. Biografia cronologica de’ bellartisti senesi: 1200–1800. Vol. 4, 1400–1450. Facsimile ed., Siena, ca. 1835. Florence: S.P.E.S., 1976., 46. In 1413 Martino was paid for unspecified work on the clockface of the hospital. See Milanesi, Gaetano. Documenti per la storia dell’arte senese. 3 vols. Siena: n.p., 1854–56., 2:32; and Gallavotti Cavallero, Daniela. Lo spedale di Santa Maria della Scala in Siena: Vicenda di una committenza artistica. Pisa: Pacini, 1985., 144, 258n34, 420, doc. 115. It should be pointed out that this document has sometimes been reported as dating to 1419. Molten cites the payment record under both dates, noting that “the date of this document is difficult to decipher, and may be from the year 1413, or the year 1419”; see Montfort Molten, Carol. “The Sienese Painter Martino di Bartolomeo.” Ph.D. diss., Indiana University, 1992., 292, 296. The present author has not had the opportunity to examine the archival source. ↩︎

-

Fattorini, Gabriele. “Giovanni di Pietro da Napoli e Martino di Bartolomeo ‘in compagnia’ nella Pisa di primo Quattrocento (con un accenno alle tele che fingevano affreschi).” Predella 39–40 (2016): 37–66., 46 (“verso il secondo decennio del Quattrocento”). ↩︎

-

The Washington triptych has been convincingly dated around 1415/20 by Miklós Boskovits; see Boskovits, Miklós. Italian Paintings of the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries. Washington, D.C.: National Gallery of Art, 2016. NGA Online Editions, https://purl.org/nga/collection/catalogue/italian-paintings-of-the-thirteenth-and-fourteenth-centuries., 254–61, no. 28. ↩︎