Maitland Fuller Griggs (1872–1943), New York, by 1926

The panel support, of a vertical wood grain, has been thinned to 2.3 centimeters and cut across the top and bottom. A dowel hole on the left edge, 33.7 centimeters from the bottom, has been cut through at just over half its diameter, suggesting that as much as 1.5 centimeters of panel thickness has been lost. No other dowel holes are in evidence. Two nail heads aligned 18 centimeters from the top edge, one 8 centimeters from the right edge and the other 6 centimeters from the left edge, indicate the placement of a batten at this height. Two partial splits in the panel extend from the top edge to the right of Saint Jerome’s cardinal’s hat to the level of his left wrist and through the gold ground to the level of the saint’s shoulder on the same side. The latter may have been provoked by the batten nail driven into the panel at that point. Both splits have resulted in minor losses in the surface, and the plugs covering both batten nails have been regilt. An approximately 2-centimeters-wide strip of regilding covers both lateral edges of the panel. The paint and gilded surfaces, which were not subjected to cleaning by Andrew Petryn in 1966–67 as was the related Saint John the Baptist panel, are otherwise in a near-perfect state of preservation: they were discovered in the course of restoration at the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, in 1999–2000 to have been protected by what is believed to be an original, undisturbed layer of varnish. This varnish was thinned, and discolored retouchings on top of it were removed and corrected at that time. The repainted spandrel areas were filled and painted out to match those of the Saint John the Baptist.

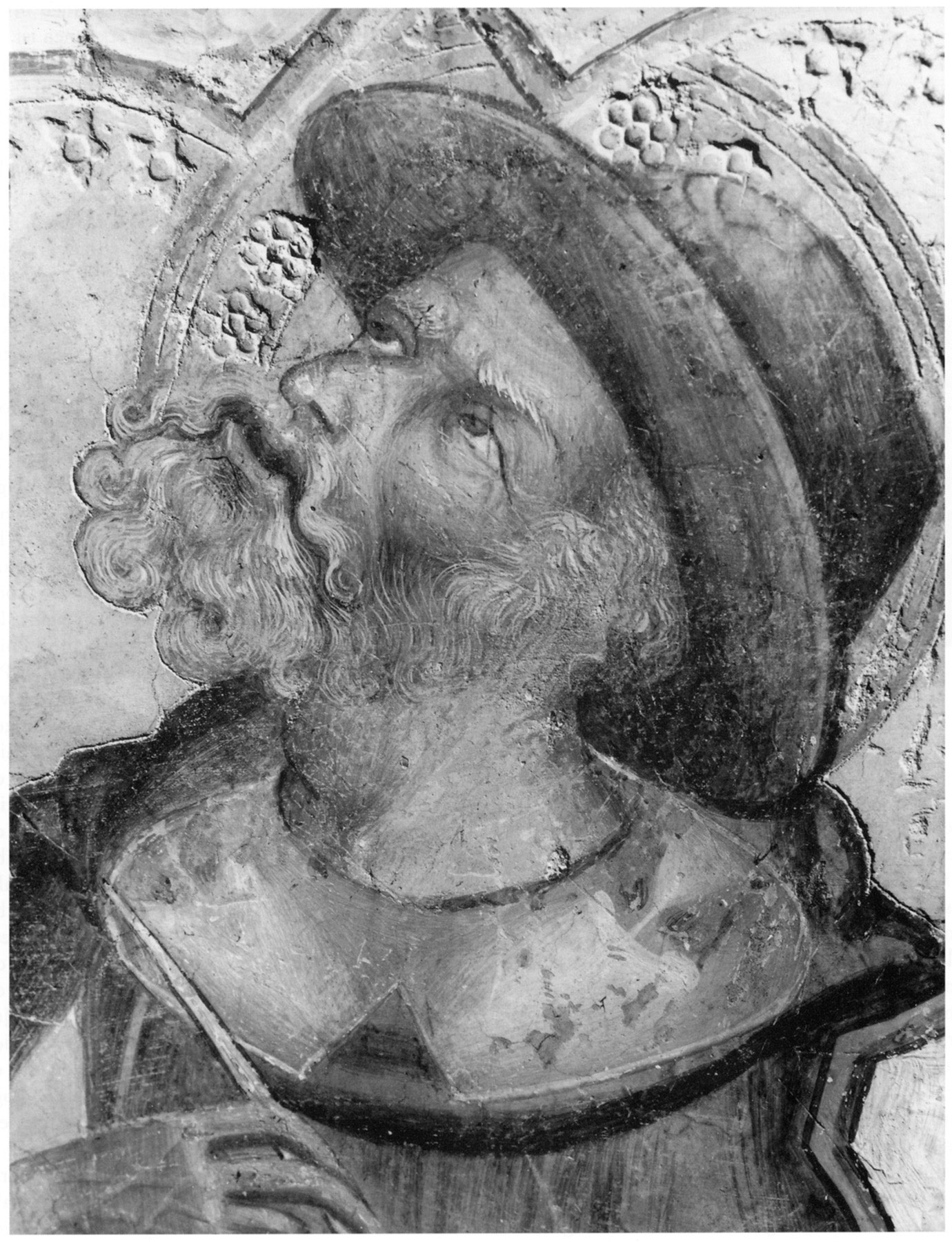

This Saint Jerome panel and the related Saint John the Baptist were lateral elements of the same unidentified complex. Based on the stance and gesture of the figures, it can be assumed that Saint John the Baptist stood to the right of a central image of the Virgin and Child, and Saint Jerome to left. Both images underwent treatment at the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, between 1999 and 2000, when it was discovered that the Saint Jerome is remarkable for being one of the rare early Italian paintings to preserve its original varnish, still beautifully intact beneath old retouchings. The removal of added layers of modern varnish over the original surface revealed, in the words of the Getty restorers, “the eloquent and subtle modeling of the face and hands, and the richness, depth, and luminosity of the colors and forms . . . [and] every nuance of the finely hatched tempera paint.”1 These qualities are conspicuously absent from the Saint John the Baptist, which is missing the top layers of paint and varnish as a result of an aggressive cleaning in 1966–67. While most of the individual details of the figure are preserved, it lacks the delicate transitions and surface brilliance of its companion, and the forms appear coarser and more hard-edged than originally intended.

There are no records of the Yale saints predating their entry into the Maitland Griggs collection, sometime before 1926. A note on the back of old photographs in the Frick Art Reference Library, New York, records Richard Offner’s verbal attribution to Taddeo di Bartolo, which has not been questioned since. Modern scholarship, following Bernard Berenson’s original assessment,2 has unanimously placed the panels among Taddeo’s earliest documented works, implicating them in the debate over the artist’s initial formation and training. Sibilla Symeonides first noted the correspondences between the Yale figures and the artist’s first signed and dated work—the 1389 polyptych for the chapel of Saint Paul at Collegarli, near San Miniato al Tedesco (Pisa) (fig. 1)—and proposed a chronology between 1389 and 1393, predating the artist’s activity in Liguria and the influence of Barnaba da Modena.3 For Symeonides, certain details in the saints’ features were directly indebted to the work of Jacopo di Mino del Pellicciaio, while others reflected the influence of Bartolo di Fredi. Charles Seymour, Jr., who followed traditional scholarship and considered Taddeo a pupil of Bartolo di Fredi, dated the Yale panels around 1390 but did not provide a discussion of their style.4 In her study of the painter, Gail Solberg deemed the Yale Saint John the Baptist and Saint Jerome “perfectly plausible heirs” of the Collegarli saints and followed Seymour in proposing a chronology around 1390, also noting that both works still manifested “uncertainties that characterize an emerging style.”5 While Solberg considered the possibility that Taddeo might have been a pupil of Jacopo di Mino—a suggestion first advanced by Berenson6—she concluded that the Yale panels, like the Collegarli altarpiece, bore no allegiance to a specific Sienese source or single master. Gaudenz Freuler, by contrast, cited the Yale panels as evidence of the impact of Bartolo di Fredi’s mature production on Taddeo’s early work, specifically highlighting their relationship to Bartolo’s four saints in the Museo Civico, Montalcino, executed around 1381/82.7 In the most recent examination of Taddeo’s early career, Gianluca Amato grouped the Yale saints with Taddeo’s Virgin and Child and Saint Peter in the Musée du Petit Palais, Avignon, France (figs. 2–3)—fragments of another unidentified structure—and placed the execution of all four panels between 1390 and 1393.8 Amato reiterated that these paintings, unlike the artist’s next signed and dated commissions—the 1395 polyptychs for the Sardi-Campiglia9 and Casassi (fig. 4) families in Pisa—showed no traces of the art of Barnaba da Modena and were still inherently tied to Sienese tradition.

Painted by Taddeo when he was around the age of twenty-seven—in the same year that his name first appears in the registers of the Sienese painters’ guild—the Collegarli altarpiece (see fig. 1) represents a touchstone for evaluating Taddeo’s formation and subsequent development.10 Long believed to have been lost, this work reappeared on the art market in 1950 and again in 1997 but is presently known only from photographs; these reveal certain inconsistencies in execution, especially noticeable in the figures of the Virgin and Child, which suggest later retouchings and interventions, possibly contemporary to its modern reframing.11 Issues of condition aside, the Collegarli Saint John the Baptist, as noted by past scholars, supplies a close analogy for the Yale saint, whose relaxed features and gentle demeanor contrast sharply with the dour, ascetic type favored by Taddeo in his later production. Compared to the Yale panels, however, the Collegarli saints are distinguished by slightly heavier, fuller proportions and complicated drapery folds that clearly anticipate the evolution of the artist’s manner in the 1395 Casassi (see fig. 4) and Sardi-Campiglia altarpieces. The Yale saints bear a less pronounced relationship to those works and reflect, instead, a different orientation in the artist’s approach, more completely beholden to Sienese examples and especially to the models of Bartolo di Fredi, as intuited by Freuler and other earlier scholars.12

The paintings that most nearly recall the Yale saints in both style and execution, as convincingly argued by Amato, are the altarpiece fragments with the Virgin and Child and Saint Peter in Avignon (see figs. 2–3). More than any other pictures by Taddeo, these images share the luminous palette and delicately nuanced execution of the present panels. Notwithstanding the abrasion to its painted surface, the Avignon Saint Peter is a close relative of the Yale Saint Jerome; both figures are characterized by virtually identical facial features and by the same painstaking definition of every single strand of gray hair and beard, including the unruly dark wisps escaping from the softly brushed curls. Following Symeonides, Amato traced the stylistic antecedents of these works to Jacopo di Mino del Pellicciaio’s models in Siena and Pisa. The closely observed naturalistic passages in the Yale Saint Jerome, however, seem incompatible with the blander, essentially flat vocabulary typical of Jacopo di Mino, whose role in Taddeo’s formation has been greatly overstated. More relevant to Taddeo’s approach is Bartolo di Fredi’s production in Montalcino in the years between around 1380 and 1388, when the artist was engaged in several major commissions for the churches of San Francesco and Sant’Agostino. The expressive figure of Saint Jerome included among the Church Fathers painted by Bartolo in the choir of Sant’Agostino, in particular, offers a concrete precedent for the sensitive handling of the Yale image (fig. 5).13 The obvious debt to such works—more than to any other Sienese prototype—suggests a plausible chronology for the Yale saints and the closely related Avignon altarpiece in the years immediately preceding the execution of the Collegarli altarpiece rather than after it, at a time when Taddeo was possibly already active in his native city and engaged in commissions in Sienese territory, before leaving for Pisa.

No other works by Taddeo that might reasonably be associated with the Yale saints have hitherto been identified. The original framing structure of the panels, which were clearly cut at the top and bottom, is uncertain. Although Solberg argued that they were most probably included in a polyptych with three-quarter-length rather than full-length figures, there is no technical evidence to support that assumption. The lack of a second (or third) dowel hole and second batten indicates only that the panels have been reduced in height, not how much has been lost. The presence of a dowel hole on only the inside edge of both panels, however, does imply either that they were the outermost panels of their complex or that the structure of which they formed part was not larger than a triptych. Remnants of painted and silver-gilded decoration, as well as round punch marks in the upper corners of both panels, suggest a framing structure similar to that in Gualtieri di Giovanni’s triptych in the Pinacoteca Nazionale, Siena.14 The convex line of punched decoration in the gold ground on each side of the figures has been described as unusual but could indicate the profile of a large capital or corbel, as in Paolo di Giovanni Fei’s altarpiece fragment with Saint John the Baptist in the Pinacoteca Stuard, Parma. —PP

Published References

Berenson, Bernard. Italian Pictures of the Renaissance: A List of the Principal Artists and Their Works with an Index of Places. Oxford: Clarendon, 1932., 552; Berenson, Bernard. Pitture italiane del Rinascimento: Catalogo dei principali artisti e delle loro opera. Trans. Emilio Cecchi. Milan: Ulrico Hoepli, 1936., 474; Perkins, F. Mason. “Taddeo di Bartolo.” In Allgemeines Lexikon der bildenden Künstler: Von der Antike bis zur Gegenwart, ed. Ulrich Thieme and Felix Becker. Leipzig, Germany: E. A. Seemann, 1938., 396; Symeonides, Sibilla. Taddeo di Bartolo. Siena: Accademia Senese degli Intronati, 1965., 34–35, 196–97, pls. 2a–b; Berenson, Bernard. Italian Pictures of the Renaissance, A List of the Principal Artists and Their Works with an Index of Places: Central Italian and North Italian Schools. 3 vols. London: Phaidon, 1968., 1:420; Seymour, Charles, Jr. Early Italian Paintings in the Yale University Art Gallery. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1970., 94–96, nos. 66–67; Fredericksen, Burton B., and Federico Zeri. Census of Pre-Nineteenth-Century Italian Paintings in North American Public Collections. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1972., 600; Charles Seymour, Jr., in Seymour, Charles, Jr., et al. Italian Primitives: The Case History of a Collection and Its Conservation. Exh. cat. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1972., 43, no. 36; Solberg, Gail E. “Taddeo di Bartolo: His Life and Work.” Ph.D. diss., Institute of Fine Arts, New York University, 1991., 30–31, 33, 294, 322, 555–57; Solberg, Gail E. “Taddeo di Bartolo at Yale.” Yale University Art Gallery Bulletin (1992): 12–25., 13–18, figs. 2–3; Freuler, Gaudenz. Bartolo di Fredi Cini: Ein Beitrag zur sienesischen Malerei des 14. Jahrhunderts. Disentis, Switzerland: Desertina, 1994., 414n18; Frinta, Mojmír S. Punched Decoration on Late Medieval Panel and Miniature Painting. Vol. 1, Catalogue Raisonné of All Punch Shapes. Prague: Maxdorf, 1998., 300, no. Gh19; Szafran, Yvonne, and Narayan Khandekar. “Varnish and Early Italian Paintings: Evidence and Implications.” In Early Italian Paintings: Approaches to Conservation; Proceedings of a Symposium at the Yale University Art Gallery, April 2002, ed. Patricia Sherwin Garland, 108–19. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 2003., 108–19, 152–53, pls. 13, 19; Amato, Gianluca. “Alcuni chiarimenti sull’attività giovanile di Taddeo di Bartolo e il caso del polittico Casassi di Pisa.” Prospettiva 134–35 (April–July 2009): 101–19., 104, figs. 3–4; Gail E. Solberg, in Strehlke, Carl Brandon, and Machtelt Brüggen Israëls, eds. The Bernard and Mary Berenson Collection of European Paintings at I Tatti. Milan: Officina Libraria, 2015., 591

Notes

-

Szafran, Yvonne, and Narayan Khandekar. “Varnish and Early Italian Paintings: Evidence and Implications.” In Early Italian Paintings: Approaches to Conservation; Proceedings of a Symposium at the Yale University Art Gallery, April 2002, ed. Patricia Sherwin Garland, 108–19. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 2003., 110. ↩︎

-

Berenson, Bernard. Italian Pictures of the Renaissance: A List of the Principal Artists and Their Works with an Index of Places. Oxford: Clarendon, 1932., 552. ↩︎

-

Symeonides, Sibilla. Taddeo di Bartolo. Siena: Accademia Senese degli Intronati, 1965., 34–35, 196–97, pls. 2a–b. ↩︎

-

Seymour, Charles, Jr. Early Italian Paintings in the Yale University Art Gallery. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1970., 94–96, nos. 66–67. ↩︎

-

Solberg, Gail E. “Taddeo di Bartolo at Yale.” Yale University Art Gallery Bulletin (1992): 12–25., 18. ↩︎

-

Berenson, Bernhard [sic]. The Central Italian Painters of the Renaissance. New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1911., 255. ↩︎

-

Freuler, Gaudenz. Bartolo di Fredi Cini: Ein Beitrag zur sienesischen Malerei des 14. Jahrhunderts. Disentis, Switzerland: Desertina, 1994., 414n18. ↩︎

-

Amato, Gianluca. “Alcuni chiarimenti sull’attività giovanile di Taddeo di Bartolo e il caso del polittico Casassi di Pisa.” Prospettiva 134–35 (April–July 2009): 101–19., 104, figs. 3–4. ↩︎

-

Szépűvészeti Múzeum, Budapest, inv. no. 53.100. ↩︎

-

The exact date of the artist’s birth is unknown but is generally placed around 1362 on the basis of a contract document dated February 7, 1386, in which Taddeo cites his father, Bartolo di Mino, a barber, as guarantor, implying that he was not yet of age—that is, under twenty-five years old. This would coincide with Vasari’s statement that Taddeo, who made his will in 1422, died at the age of fifty-nine. See Solberg, Gail E. “Taddeo di Bartolo: His Life and Work.” Ph.D. diss., Institute of Fine Arts, New York University, 1991., 7. ↩︎

-

The polyptych remained in situ until 1767 and then disappeared from view until it resurfaced in a sale at Christie’s, London, December 8, 1950, only to vanish again and reemerge in a sale at Sotheby’s, London, December 3, 1997, lot 56. Based on stylistic considerations alone, it is difficult to concur with Carl Strehlke’s and Gail Solberg’s proposals to associate with the Collegarli altarpiece a predella fragment with saints in Philadelphia (Philadelphia Museum of Art, John G. Johnson Collection, inv. no. 95) and two pinnacles with the Annunciation in Bergen, Norway (Kode—Art Museums and Composer Homes, inv. no. 2). See Strehlke, Carl Brandon. “Sienese Paintings in the Johnson Collection.” Paragone 36, no. 427 (1985): 3–15., 5–6; Solberg, Gail E. “Taddeo di Bartolo: His Life and Work.” Ph.D. diss., Institute of Fine Arts, New York University, 1991., 321–24; and Solberg, Gail E. Taddeo di Bartolo. Exh. cat. Cinisello Balsamo, Milan: Silvana, 2020., 150–51, no. 30. ↩︎

-

The dominant influence of Bartolo di Fredi on the artist’s formation was stressed by Perkins, F. Mason. “Taddeo di Bartolo.” In Allgemeines Lexikon der bildenden Künstler: Von der Antike bis zur Gegenwart, ed. Ulrich Thieme and Felix Becker. Leipzig, Germany: E. A. Seemann, 1938.. ↩︎

-

For these frescoes, see Freuler, Gaudenz. Bartolo di Fredi Cini: Ein Beitrag zur sienesischen Malerei des 14. Jahrhunderts. Disentis, Switzerland: Desertina, 1994., 224–59, 485–88, no. 71. ↩︎

-

Inv. no. 140. ↩︎