Sale, Sotheby’s, London, March 16, 1966, lot 27; “Salocchi”; with Vittore Frascione, Florence, 1968–69; private collection, Italy, and by descent; sale, Bonhams, London, July 3, 2013, lot 55; Richard L. Feigen (1930–2021), New York

The panel support, of a vertical wood grain and a depth of 2.0 centimeters, retains its original thickness but has been cut on all four sides. It comprises one large plank, 42.7 centimeters wide, with a smaller 4.6-centimeters-wide strip added to it at the right (fig. 1). At some point, presumably when the panel was cut to a half-length format, the upper edge was also cut to form a rounded arch: the present upper-left and upper-right corners of the panel are modern inserts to return it to a rectangular shape. The main plank of the support features a large knot near its upper-right edge, provoking an unusually pronounced swirl to the wood grain around it. Scribed marks for a horizontal batten, 6.7 centimeters wide and 11 centimeters below the present top edge of the panel, are clearly visible on the reverse. Two iron nails driven through the center of this batten, 4.3 and 31.4 centimeters from the present left edge of the panel, are still visible, while a hole that may have housed a third nail, 44.5 centimeters from the left edge, is now empty.

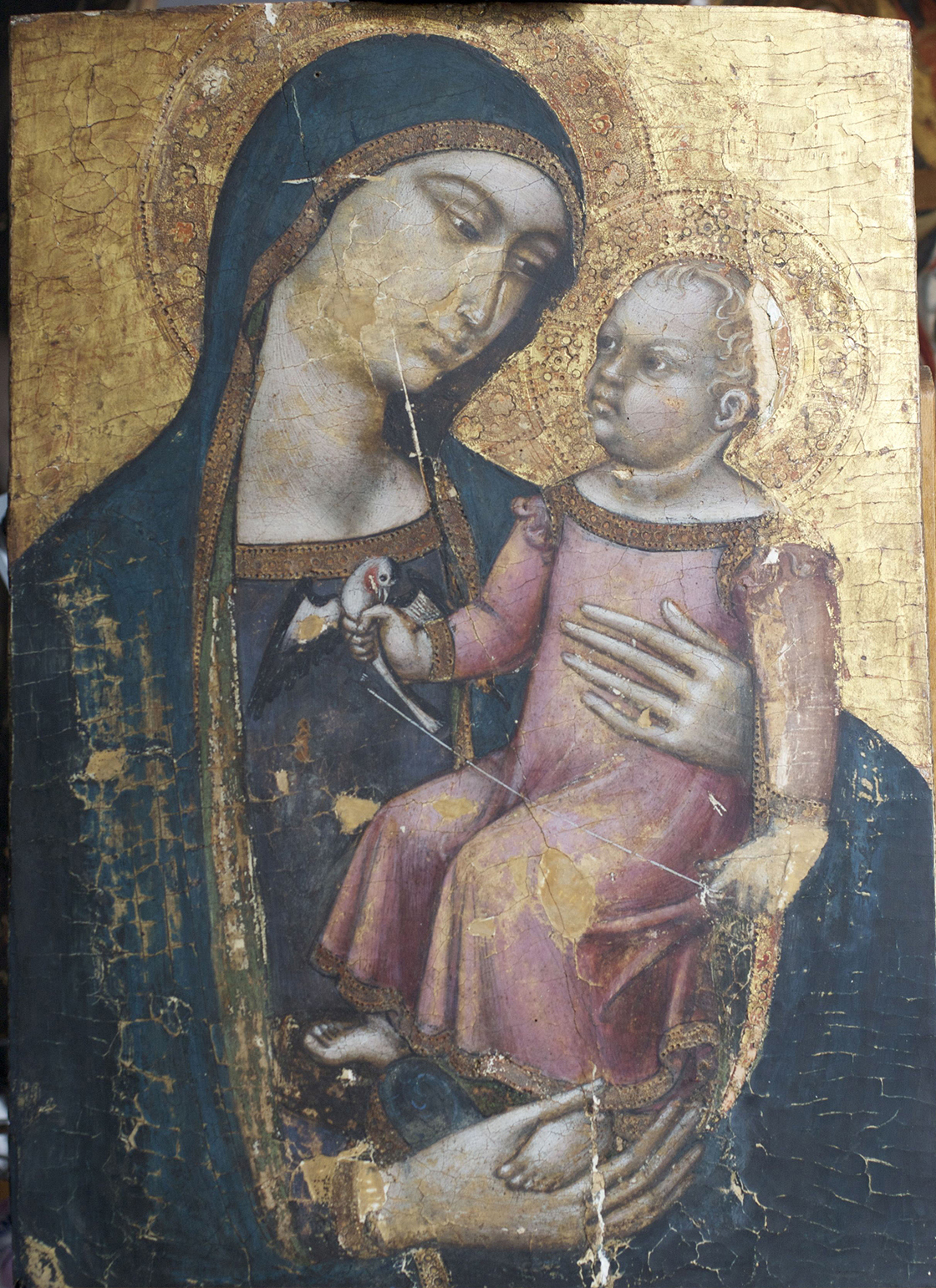

The paint surface has suffered extensive losses and localized abrasion (fig. 2). The gilding of the haloes, except as noted below, is original although worn. Outside the haloes, there are two campaigns of modern gilding on the panel. One, surrounding the Virgin’s halo, appears to be laid over original gesso. The other, executed over new gesso, covers the inserts at the upper corners, a strip of damage along the left edge of the panel, and a large area of total loss to the right of an irregular line approximately 11 centimeters from the right edge of the panel, running vertically through the Child’s left hand and arm, the back of His head, and including the right third of His halo. The paint in the lower half of the panel to the right of this line is also modern. A split following the wood grain on a slight diagonal through the panel, from 18 centimeters off the right edge at the bottom to 32.5 centimeters off the right edge at the top, has provoked smaller, local paint losses, most prominently in the area of the Child’s left knee and thigh and the Virgin’s jaw. Losses are also scattered throughout the Virgin’s blue mantle at the left of the painting, including a large irregular total loss along the left edge of the panel, from the Virgin’s elbow through her shoulder. Where the flesh tones and features are not interrupted by these losses or by abrasions associated with old repairs, they are beautifully preserved and reveal a confident and accomplished technique. Vigorous underdrawing is plainly visible through the lavender robe of the Christ Child. The painting was last cleaned and restored in Florence in 2014 by Daniele Rossi.

The few scholars to have considered this painting appear to have known it in photograph only, and none of them was fully aware of its compromised condition. In its present reduced format, it is presented as an object of private devotion, but the indications of a batten on its reverse (see fig. 1) reveal that it was designed as the center panel of an altarpiece polyptych. The placement of this batten must coincide with the height at which the gables of the lateral panels met that of the center panel, slightly above the spring of its framing arch. The presence of one batten alone, however, cannot reveal whether the original format of the altarpiece included three-quarter-length figures, in which case only a single batten at the bottom of the structure is missing, or full-length figures, in which case two battens are probably missing: one along the center and one across the bottom of the structure. The overwhelming majority of Luca di Tommè’s liturgical commissions include full-length figures, and in every altarpiece by the artist in which the center panel shows a full-length Virgin and Child, the Virgin is seated on a throne draped with a cloth of honor; only in the three-quarter-length polyptych no. 586 in the Pinacoteca Nazionale, Siena, does she appear directly against a gold ground. It is possible that the regilding of the ground outside the haloes in the Yale panel was intended to mask a fragmentary throne and cloth of honor, completing the illusion of its revised function as a private devotional work. The presence of red paint or glaze—and what appears to be sgraffito granulation simulating a textile pattern atop gilding and bolus in the small triangular patch above the Virgin’s left shoulder, below the two overlapping haloes—tends to support the reconstruction of the composition as a Virgin and Child Enthroned.

If any other fragments survive from the altarpiece of which this panel formed part, the most likely candidates would be the full-length figures of Saints Peter and Paul now displayed in the chapel at Exeter College, Oxford (figs. 3–4).1 The rounded and heavily shaded features of the two apostles are an exact stylistic match for the Yale Virgin and Child, the haloes of all four figures are similarly decorated, and the three panels are compatible in scale, to the extent that the original format of the Yale panel can be approximately reconstructed. Two deformations of the gilded surface in the Exeter Saint Paul, just within the framing arch at roughly the level of the saint’s ears, may indicate nails securing a horizontal batten; the corresponding area in the Exeter Saint Peter has been damaged and repaired. It has not been possible to inspect the reverse of these panels to determine if scribed lines are preserved indicating the batten’s placement and, accordingly, if it corresponds in width to that on the reverse of the Yale Virgin and Child.

The Exeter Saint Peter and Saint Paul were presented to the College Chapel ca. 1920 by George Gidley Robinson, who had been a fellow at Exeter from 1873 to 1878; their earlier provenance is unknown. Sherwood Fehm proposed an alternative reconstruction for these panels as parts of a dismembered polyptych in the church of San Francesco at Mercatello sul Metauro, but this is demonstrably incorrect.2 The lateral panel with Saint Anthony Abbot still in situ at Mercatello sul Metauro is larger than the Exeter Saints, is framed differently from them (its spandrels rise from a different height and at a much gentler slope), and is considerably later in date. It and the Enthroned Virgin preserved alongside it at Mercatello sul Metauro are undoubtedly works of the 1380s, painted quite late in Luca di Tommè’s career. While Gaudenz Freuler, as quoted in the catalogue of the Bonhams sale of July 2013, suggested a date of ca. 1380 for the panel now at Yale, it, along with the Exeter Saints, is likely to have been painted around the time of the 1367 altarpiece of the Sant’Anna Meterza in the Pinacoteca Nazionale, Siena,3 probably not later than Luca’s Rieti altarpiece of 1370. Two of the punch tools used in the Yale Virgin and Child—Erling Skaug’s no. 547 and one punch not catalogued by Skaug, no. La123 in Mojmír Frinta’s catalogue—recur in the Rieti altarpiece.4 The latter is also found in the Exeter Saints. The third tool in the Yale panel, Skaug no. 609, was shared by Bartolomeo Bulgarini and Niccolò di Ser Sozzo. Luca di Tommè signed an altarpiece jointly with Niccolò di Ser Sozzo in 1362, one year before the latter’s death, which might be taken as a hypothetical terminus post quem for Luca’s acquisition of Niccolò’s punch tools.

Two further panels might tentatively be considered candidates to complete a reconstruction with the Yale and Exeter panels: full-length figures of Saint John the Baptist and Saint John the Evangelist last recorded in the Lanckoronski collection in Vienna in 1935.5 These were included by Fehm in a hypothetical reconstruction of another altarpiece, including panels of the Mystic Marriage of Saint Catherine, Saint Bartholomew, and Saint Blaise in the Pinacoteca Nazionale, Siena.6 While that reconstruction is not overtly implausible, neither is it especially compelling, whereas old photographs of the Lanckoronski panels suggest a strong stylistic link to the two saints at Exeter College. Barring retrieval of these panels, this question can be nothing more than a conjectural proposition.

The motif of the Christ Child holding a goldfinch tied to a string refers to the symbolism of a bird escaping a snare (Psalm 124:7) as a metaphor for the freedom of the human soul. In medieval lore, the goldfinch was said to have acquired the red spot on his breast after pulling a thorn from Christ’s crown on the way to Calvary and being splashed by a drop of the holy blood. In the Yale Virgin and Child, the finch nips at the Christ Child’s thumb with his beak, evoking the splash of blood. The finch was also a commonly accepted symbol of the Virgin’s foreknowledge of her Son’s Passion, due to its habit of feeding off the seeds of thistles. Captive goldfinches were reputedly a favorite pet of children in wealthy or aristocratic families. Luca di Tommè has successfully alluded to his patrons’ likely familiarity with the bird by showing it straining against the string tied to its foot and wound twice around the Child’s finger to prevent its escape. —LK

Published References

Gregori, Mina. “Dipinti e sculture: Biennale Internazionale dell’Antiquariato, Firenze.” Arte illustrata 2 (1969): 110–16., 112; Fehm, Sherwood A., Jr. “Luca di Tommè’s Influence on Three Sienese Masters: The Master of the Magdalene Legend, the Master of the Panzano Triptych, and the Master of the Pietà.” Mitteilungen des Kunsthistorischen Institutes in Florenz 20 (1976): 333–50., 348; De Benedictis, Cristina. La pittura senese, 1330–1370. Florence: Salimbeni, 1979., 38, 66, 89; Fehm, Sherwood A., Jr. Luca di Tommè: A Sienese Fourteenth-Century Painter. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 1986., 165, no. 64

Notes

-

Both of these panels have been truncated at the bottom; see Fehm, Sherwood A., Jr. Luca di Tommè: A Sienese Fourteenth-Century Painter. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 1986., 104–5. ↩︎

-

Fehm, Sherwood A., Jr. “A Reconstruction of an Altar-Piece by Luca di Tommè.” Burlington Magazine 115, no. 844 (July 1973): 463–66., 463–64. ↩︎

-

Inv. no. 109. ↩︎

-

Skaug, Erling S. Punch Marks from Giotto to Fra Angelico: Attribution, Chronology, and Workshop Relationships in Tuscan Panel Painting, with Particular Consideration to Florence, c. 1330–1430. 2 vols. Oslo: International Institute for Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works—Nordic Group, 1994., 2: no. 547; and Frinta, Mojmír S. Punched Decoration on Late Medieval Panel and Miniature Painting. Vol. 1, Catalogue Raisonné of All Punch Shapes. Prague: Maxdorf, 1998., no. La123. ↩︎

-

Fehm, Sherwood A., Jr. Luca di Tommè: A Sienese Fourteenth-Century Painter. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 1986., 116–17. The panels are not included in Skubiszewska, Maria, and Kazimierz Kuczman. Paintings from the Lanckoronski Collection from the 14th through 16th Centuries in the Collections of the Wawel Royal Castle. Kraków, Poland: Wawel Royal Castle, 2010.. ↩︎

-

Inv. no. 594; Fehm, Sherwood A., Jr. Luca di Tommè: A Sienese Fourteenth-Century Painter. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 1986., 114–15. Torriti, Piero. La Pinacoteca Nazionale di Siena. Vol. 1, I dipinti dal XII al XV secolo. Genoa: Sagep, 1977., 435, lists these paintings as “lost” (“non rintracciato”). Photographs of them published by Fehm leave an attribution to Luca di Tommè doubtful. ↩︎