Oratorio del Podere Gazzaja, Arezzo (environs), to 1818;1 James Jackson Jarves (1818–1888), Florence, by 1859

The panel support, of a vertical grain, is 2.5 centimeters thick and has been cradled and waxed. All the vertical frame members attached to it are modern, as is the predella, the capitals at the sides, and the corbels supporting the central arches. All the frame moldings outside of the central trefoil medallion, which measures 17.5 by 14.5 centimeters, and lateral roundels, which are 5.4 centimeters in diameter, have been regilt to match the gilding of the additions. The paint surface and gilding are otherwise in excellent condition, displaying virtually no abrasion or flaking except for minor repaints covering small irregular losses along the bottom edge of the image. A split rising from the bottom, 23 to 24 centimeters from the left edge and extending 28 centimeters above the predella, has provoked no attendant losses of paint or gilding.

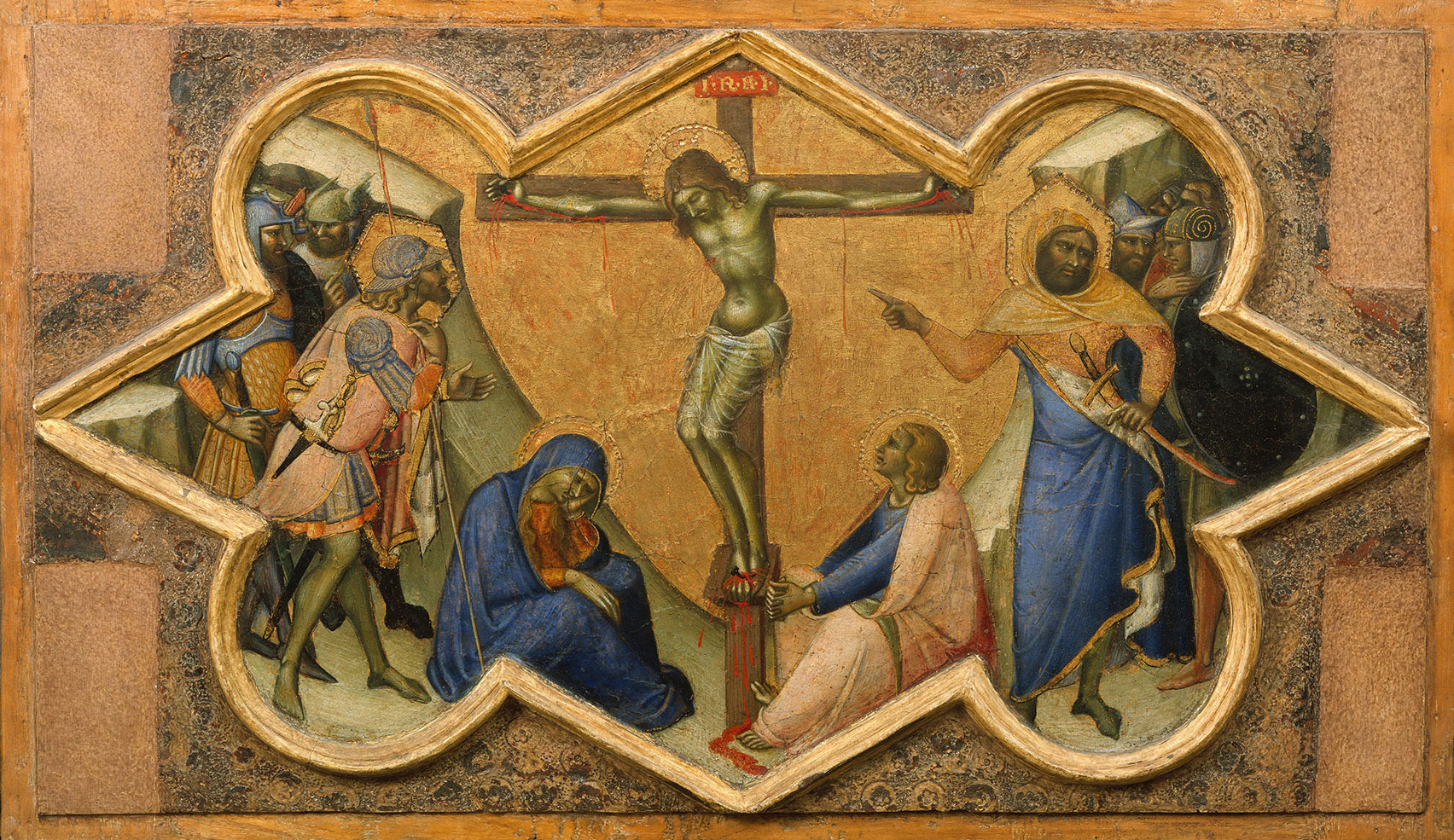

One of the best known and most widely discussed paintings in the collection of the Yale University Art Gallery, Luca di Tommè’s Assumption of the Virgin is also one of the best preserved—having largely escaped the dramatic excesses of the 1950s cleaning campaigns at Yale—and least controversial. It is exceptional among fourteenth-century Italian paintings for the extent, intricacy, and delicacy of its sgraffito gilt decoration and embellishment with oil glazes, much of which survives intact. The material cost and time-consuming labor of these decorative effects—ranging from the lavish patterning of “brocade” fabrics worn by the Virgin and the orders of angels who support her mandorla in the foreground or sing her praises as she ascends to Heaven, to the outlining in gold of the vanes of the feathers in the angels’ wings and in the blue and red seraphim and cherubim that fill the ogival framing and circular medallions above—is particularly astonishing given the probability that the panel was originally meant to be viewed from three or more meters off the floor. The conspicuous opulence of the complete structure of which it formed part is unique among Italian ecclesiastical commissions of its day, leaving the total absence of documentation concerning its genesis and the lack of a continuous trail of provenance all the more bewildering.

The Assumption of the Virgin was acquired by James Jackson Jarves in the 1850s as an anonymous work of the mid-fourteenth-century Sienese school, and it is referred to as such in all nineteenth-century publications.2 The first scholar to attempt a more specific classification for the painting was F. Mason Perkins, who assigned it to Bartolo di Fredi and compared it to the altarpiece of the same subject in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston,3 which was then thought to be by that artist (though it has subsequently been recognized as a typical work of Niccolò di Ser Sozzo), and to the miniature of the Caleffo, also representing the Assumption of the Virgin, in the Archivio di Stato di Siena, a signed work by Niccolò di Ser Sozzo.4 Perkins’s attribution was echoed by Bernard Berenson in the 1909 edition of his lists of Italian paintings but has otherwise not been repeated by any other author.5 Perkins corrected his own assessment of the Yale Assumption in 1909, attributing it to Luca di Tommè.6 This attribution was endorsed by Osvald Sirén in his 1916 catalogue of the Jarves Collection and has been assumed to be fact by nearly all writers since.7 Only Raimond van Marle, Pietro Toesca, Mario Bucci, and Mario Rotili have demurred, preferring to assign the painting to Niccolò di Ser Sozzo.8 Federico Zeri discussed it as by both Niccolò di Ser Sozzo and Luca di Tommè.9 A number of writers since then, clinging to the attribution to Luca di Tommè, have pointed out how close the artist approaches to the example of Niccolò di Ser Sozzo in this work. Henk van Os, finally, followed by Pia Palladino, proposed that the Yale Assumption might have been the central pinnacle to the 1362 altarpiece from San Tommaso degli Umiliati (fig. 1), a work signed jointly by Niccolò di Ser Sozzo and Luca di Tommè.10

It is remarkable that until the publications of van Os and Palladino, no scholar had wondered what function the Yale Assumption might have fulfilled. The painting was repeatedly compared to three versions of the same subject by Niccolò di Ser Sozzo—one manuscript illumination and two center panels of full-scale altarpieces—but only to discuss its iconography. In fact, the size and shape of the Yale panel are appropriate only to the central pinnacle of an unusually large altarpiece. Furthermore, of all surviving altarpieces painted in the early decades of the second half of the fourteenth century, few if any are as large as the Umiliati altarpiece of 1362, and that painting, in turn, is perhaps the only structure large enough to have accommodated the Yale panel as its central pinnacle. That earlier generations of scholars did not leap to this conclusion is understandable, given that the Yale panel was first correctly attributed to Luca di Tommè in 1909, but the Umiliati altarpiece was believed until 1932 to be by Bartolo di Fredi. In that year, Cesare Brandi discovered the inscription in the framing socle beneath its central panel—“NICCHOLAUS SER SOCCII ET LUCAS TOMAS DE SENIS HOC OPUS PINSERUNT ANNI MCCCLXII” (Niccolò di Ser Sozzo and Luca di Tommè of Siena painted this work in the year 1362)11—and discussion of the work since then has focused on the relative contribution of either master to its design or execution. Majority opinion at first assigned the invention and the lion’s share of the execution of this important complex to Niccolò di Ser Sozzo, proceeding on the a priori argument that he was the older of the two painters and therefore that Luca di Tommè would have been employed merely as his assistant, possibly as his apprentice. Following the logic of this narrative, the Yale Assumption would necessarily have been a later, more mature work by Luca di Tommè.

The presumption of Luca di Tommè’s subordinate role in the genesis of the Umiliati altarpiece was reinforced by the nature of the prevailing taste for Sienese painting in the mid-twentieth century, which admired the lively palette and naively calligraphic drawing style of Niccolò di Ser Sozzo at the expense of what was perceived to be the inadequately imaginative (sometimes described as derivatively Florentine) and somber naturalism of Luca di Tommè. This situation began to change only after Millard Meiss adopted Luca di Tommè as one of the protagonists of the post-plague style that he asserted to be dominant in Siena in the second half of the fourteenth century.12 A new view that the two painters might have been engaged as equal partners rather than as master and assistant gained traction with Zeri’s recognition of five predella panels in the Crawford collection at Balcarres and the Pinacoteca Vaticana (fig. 2)—all clearly painted by Luca di Tommè—as comprising the missing predella of the Umiliati altarpiece. Discussion of their collaboration from that point forward was invariably more granular, if not always more persuasive, culminating in the recognition that, in addition to the predella, Luca painted at least the figure of Saint John the Baptist in the leftmost panel of the main tier of the altarpiece and possibly the figure of Saint Thomas alongside him as well, while Niccolò was responsible for the central and two right-hand panels.13 Within this working paradigm, there is no intellectual obstacle to recognizing the Yale Assumption as the central pinnacle from this complex. Palladino’s cogent comparisons of it to the Balcarres and Vatican predella panels confirm not only its original association with them as parts of the same altarpiece but also its unqualified attribution to Luca di Tommè.

There is no record of the original patron or even location of the Umiliati altarpiece. It is presumed to have been painted for the church of San Tommaso, then officiated by the Umiliati, solely on the basis of its iconography: Saint Thomas occupies the position of honor immediately to the Virgin’s right (the viewer’s left, facing the altarpiece) and four of the five predella panels are dedicated to scenes from his life. The order of the Umiliati was suppressed by Pope Pius V in 1571, but even before this, the church of San Tommaso in Siena was reassigned (1554–59) to a community of Clarissans. Early published sources do not cite the Saint Thomas altarpiece there or elsewhere, and the source of its transfer to the Pinacoteca Nazionale, presumably at its founding in the post-Napoleonic era, is also unrecorded. —LK

Published References

Jarves, James Jackson. Descriptive Catalogue of “Old Masters” Collected by James J. Jarves to Illustrate the History of Painting from A.D. 1200 to the Best Periods of Italian Art. Cambridge, Mass.: H. O. Houghton, 1860., 46, no. 40; Jarves, James Jackson. Art Studies: The “Old Masters” of Italy; Painting. New York: Derby and Jackson, 1861., pl. B; Sturgis, Russell, Jr. Manual of the Jarves Collection of Early Italian Pictures. New Haven: Yale College, 1868., 40–44; W. F. Brown, Boston. Catalogue of the Jarves Collection of Early Italian Pictures. Sale cat. November 9, 1871., 16, no. 35; Rankin, William. “Some Early Italian Pictures in the Jarves Collection of the Yale School of Fine Arts at New Haven.” American Journal of Archaeology 10, no. 2 (April–June 1895): 137–51., 142–43; Perkins, F. Mason. “Pitture senesi negli Stati Uniti.” Rassegna d’arte senese 1 (1905): 74–78., 76; Rankin, William. Notes on the Collections of Old Masters at Yale University, the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, the Fogg Museum of Harvard University. Wellesley, Mass.: Department of Art, Wellesley College, 1905., 9, no. 35; Berenson, Bernard. The Florentine Painters of the Renaissance with an Index to Their Works. 3rd. ed. New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1909., 141; Perkins, F. Mason. “Un dipinto ignorato della scuola senese.” Rassegna d’arte senese 9, no. 3 (March 1909): 41–42.; Mather, Frank Jewett, Jr. “The Jarves Collection.” Yale Alumni Weekly 23 (1914): 968–69., 967; Sirén, Osvald. A Descriptive Catalogue of the Pictures in the Jarves Collection Belonging to Yale University. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1916., 37–38, no. 12; van Marle, Raimond. Simone Martini et les peintres de son école. Strasbourg, France: J. H. E. Heitz, 1920., 144–45; Perkins, F. Mason. “Some Sienese Paintings in American Collections: Part Two.” Art in America 8, no. 6 (October 1920): 272–92., 288; DeWald, Ernest. “The Master of the Ovile Madonna.” Art Studies 1 (1923): 45–54., 54, no. 24; Mather, Frank Jewett, Jr. A History of Italian Painting. New York: H. Holt, 1923., 86, fig. 54; van Marle, Raimond. The Development of the Italian Schools of Painting. Vol. 2. The Hague: M. Nijhoff, 1924., 481, fig. 313; Offner, Richard. Italian Primitives at Yale University: Comments and Revisions. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1927., 4–5, 38–39, figs. 29–29a; Cecchi, Emilio. Les peintres siennois. Paris: G. Crès, 1928., 148, pl. 223; Comstock, Helen. “Luca di Tommè in American Collections.” International Studio 89, no. 368 (January 1928): 57–62., 58–59; Perkins, F. Mason. “Luca di Tommè.” In Allgemeines Lexikon der bildenden Künstler: Von der Antike bis zur Gegenwart, ed. Ulrich Thieme and Felix Becker. Leipzig, Germany: E. A. Seemann, 1929., 427; “Handbook: A Description of the Gallery of Fine Arts and the Collections,” special issue, Bulletin of the Associates in Fine Arts at Yale University 5, nos. 1–3 (1931): 1–64., 28; van Marle, Raimond. “Ancora quadri senesi.” La Diana 6, no. 3 (1931): 168–76., 170; Venturi, Lionello. Pitture italiane in America. 2 vols. Milan: Ulrico Hoepli, 1931., pl. 84; Berenson, Bernard. Italian Pictures of the Renaissance: A List of the Principal Artists and Their Works with an Index of Places. Oxford: Clarendon, 1932., 313; Edgell, George Harold. A History of Sienese Painting. New York: Dial, 1932., 157, fig. 191; van Marle, Raimond. Le scuole della pittura italiana. Vol. 2, La scuola senese del XIV secolo. The Hague: M. Nijhoff, 1934., 512; Berenson, Bernard. Pitture italiane del Rinascimento: Catalogo dei principali artisti e delle loro opera. Trans. Emilio Cecchi. Milan: Ulrico Hoepli, 1936., 269; New York Herald Tribune, January 11, 1945, pl. 1; Comstock, Helen. “The Yale Collection of Italian Paintings.” Connoisseur 118 (September 1946): 45–52., 51, no. 9; “Picture Book Number One: Italian Painting,” special issue, Bulletin of the Associates in Fine Arts at Yale University 15, nos. 1–3 (October 1946): n.p., fig. 22; Meiss, Millard. Painting in Florence and Siena after the Black Death: The Arts, Religion, and Society in the Mid-Fourteenth Century. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1951., 21–24, fig. 21; Steegmuller, Francis. The Two Lives of James Jackson Jarves. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1951., 297; Toesca, Pietro. Il trecento. Turin: Unione Tipografico Editrice Torinese, 1951., 2:594–97, fig. 525; Mazzini, Franco. “Resti di un ciclo senese trecentesco in S. Domenico d’Urbino.” Bollettino d’arte 37 (1952): 61–66., 65–66n18; International Style: The Arts in Europe around 1400. Exh. cat. Baltimore: Walter Art Gallery, 1962., 18; Dalli Regoli, Gigetta. Miniatura pisana del trecento. Vicenza: Neri Pozza, 1963.; Meiss, Millard. “Notes on Three Linked Sienese Styles.” Art Bulletin 45, no. 1 (March 1963): 47–48., 47–48, fig. 7; 56; Meiss, Millard. Painting in Florence and Siena after the Black Death: The Arts, Religion, and Society in the Mid-Fourteenth Century. New York: Harper and Row, 1964., 21–24; Bucci, Mario. “Proposte per Niccolò di Ser Sozzo Tegliacci.” Paragone 16, no. 181 (March 1965): 52–60., 59n2; Klesse, Brigitte. Seidenstoffe in der italienischen Malerei des 14. Jahrhunderts. Bern, Switzerland: Stämpfli, 1967., 259, no. 151k, 407, no. 394e; Berenson, Bernard. Italian Pictures of the Renaissance, A List of the Principal Artists and Their Works with an Index of Places: Central Italian and North Italian Schools. 3 vols. London: Phaidon, 1968., 1:225, 2: pl. 368; Rotili, Mario. La miniatura gotica in Italia. 2 vols. Naples: Libreria Scientifica, 1968–69., 2:17; Fehm, Sherwood A., Jr. “Notes on the Exhibition of Sienese Paintings from Dutch Collections.” Burlington Magazine 111, no. 798 (September 1969): 574–77., 574, fig. 7; Mongan, Agnes, and Elizabeth Mongan. European Paintings in the Timken Art Gallery. San Diego: Putnam Foundation, 1969., 22; van Os, Henk. Marias Demut und Verherrlichung in der sienesischen Malerei, 1300–1450. The Hague: Staatsgeverij, 1969., 166n56, 170n65; Fehm, Sherwood A., Jr. “Luca di Tommè.” Ph.D. diss., Yale University, 1971., viii, pl. 31; Seymour, Charles, Jr. Early Italian Paintings in the Yale University Art Gallery. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1970., 78–80, no. 53; Fredericksen, Burton B., and Federico Zeri. Census of Pre-Nineteenth-Century Italian Paintings in North American Public Collections. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1972., 113, 307, 599; Charles Seymour, Jr., in Seymour, Charles, Jr., et al. Italian Primitives: The Case History of a Collection and Its Conservation. Exh. cat. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1972., 13, no. 4, figs. 4a–b; Muller, Norman E. “Observations on the Painting Technique of Luca di Tommè.” Los Angeles County Museum of Art Bulletin 19, no. 2 (1973): 12–21., 16, 21n32; Fehm, Sherwood A., Jr. “Luca di Tommè’s Influence on Three Sienese Masters: The Master of the Magdalene Legend, the Master of the Panzano Triptych, and the Master of the Pietà.” Mitteilungen des Kunsthistorischen Institutes in Florenz 20 (1976): 333–50., 333n2; De Benedictis, Cristina. La pittura senese, 1330–1370. Florence: Salimbeni, 1979., 47–48, 88, fig. 89; Cole, Bruce. Sienese Painting from Its Origins to the Fifteenth Century. New York: Harper and Row, 1980., 191–92, 195, fig. 101; Duncan Phillips, in Shestack, Alan, ed. Yale University Art Gallery: Selections. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1983., 24–25; Fehm, Sherwood A., Jr. Luca di Tommè: A Sienese Fourteenth-Century Painter. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 1986., 1, 26–30, 85–88, no. 15, pls. 15-1 to 15-5; van Os, Henk. Sienese Altarpieces, 1215–1460: Form, Content, Function. Vol. 1, 1215–1460. Groningen, Netherlands: Egbert Forsten, 1984., 46–47, fig. 18; Skaug, Erling S. Punch Marks from Giotto to Fra Angelico: Attribution, Chronology, and Workshop Relationships in Tuscan Panel Painting, with Particular Consideration to Florence, c. 1330–1430. 2 vols. Oslo: International Institute for Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works—Nordic Group, 1994., 1:247; Palladino, Pia. Art and Devotion in Siena after 1350: Luca di Tommè and Niccolò di Buonaccorso. Exh. cat. San Diego: Timken Museum of Art, 1997., 34–35, fig. 25; Frinta, Mojmír S. Punched Decoration on Late Medieval Panel and Miniature Painting. Vol. 1, Catalogue Raisonné of All Punch Shapes. Prague: Maxdorf, 1998., 51; Chelazzi Dini, Giulietta, Alessandro Angelini, and Bernardina Sani. Pittura senese. Milan: Federico Motta, 2002., 187

Notes

-

Removed from an altar by permission of the bishop of Arezzo and transferred to the private chapel of the noble Agazzari family in Siena, who owned it. ↩︎

-

Jarves, James Jackson. Descriptive Catalogue of “Old Masters” Collected by James J. Jarves to Illustrate the History of Painting from A.D. 1200 to the Best Periods of Italian Art. Cambridge, Mass.: H. O. Houghton, 1860., 46, no. 40; Jarves, James Jackson. Art Studies: The “Old Masters” of Italy; Painting. New York: Derby and Jackson, 1861., pl. B; Sturgis, Russell, Jr. Manual of the Jarves Collection of Early Italian Pictures. New Haven: Yale College, 1868., 40–44; W. F. Brown, Boston. Catalogue of the Jarves Collection of Early Italian Pictures. Sale cat. November 9, 1871., 16, no. 35; and Rankin, William. “Some Early Italian Pictures in the Jarves Collection of the Yale School of Fine Arts at New Haven.” American Journal of Archaeology 10, no. 2 (April–June 1895): 137–51., 142–43. ↩︎

-

Inv. no. 83.175a–c, https://collections.mfa.org/objects/30920/saints-augustine-and-peter-left-panel?ctx=28021073-0af0-4a4f-92a2-3184af3133c3&idx=1, https://collections.mfa.org/objects/30919/the-dormition-and-assumption-of-the-virgin-center-panel?ctx=47727eae-e210-4ff5-b2e8-cf3672814954&idx=0, and https://collections.mfa.org/objects/30921/saint-john-the-evangelist-and-a-deacon-saint-right-panel?ctx=28021073-0af0-4a4f-92a2-3184af3133c3&idx=2. ↩︎

-

MS Capitoli 2; Perkins, F. Mason. “Pitture senesi negli Stati Uniti.” Rassegna d’arte senese 1 (1905): 74–78., 76. ↩︎

-

Berenson, Bernard. The Florentine Painters of the Renaissance with an Index to Their Works. 3rd. ed. New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1909., 141. ↩︎

-

Perkins, F. Mason. “Un dipinto ignorato della scuola senese.” Rassegna d’arte senese 9, no. 3 (March 1909): 41–42.. ↩︎

-

Sirén, Osvald. A Descriptive Catalogue of the Pictures in the Jarves Collection Belonging to Yale University. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1916., 37–38, no. 12. ↩︎

-

van Marle, Raimond. Le scuole della pittura italiana. Vol. 2, La scuola senese del XIV secolo. The Hague: M. Nijhoff, 1934., 512; Toesca, Pietro. Il trecento. Turin: Unione Tipografico Editrice Torinese, 1951., 2:594–97, fig. 525; Bucci, Mario. “Proposte per Niccolò di Ser Sozzo Tegliacci.” Paragone 16, no. 181 (March 1965): 52–60., 59n2; and Rotili, Mario. La miniatura gotica in Italia. 2 vols. Naples: Libreria Scientifica, 1968–69., 2:17. ↩︎

-

Zeri, Federico. “Sul problema di Niccolò Tegliacci e Luca di Tommè.” Paragone 105 (1958): 3–16., 3–16. ↩︎

-

van Os, Henk. Sienese Altarpieces, 1215–1460: Form, Content, Function. Vol. 1, 1215–1460. Groningen, Netherlands: Egbert Forsten, 1984., 46–47, fig. 18; and Palladino, Pia. Art and Devotion in Siena after 1350: Luca di Tommè and Niccolò di Buonaccorso. Exh. cat. San Diego: Timken Museum of Art, 1997., 34–35, fig. 25. ↩︎

-

Brandi, Cesare. “Niccolò di Ser Sozzo Tegliacci.” L’arte 2 (1932)., 223–36. ↩︎

-

Meiss, Millard. Painting in Florence and Siena after the Black Death: The Arts, Religion, and Society in the Mid-Fourteenth Century. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1951., 21–24, fig. 21. ↩︎

-

Palladino, Pia. Art and Devotion in Siena after 1350: Luca di Tommè and Niccolò di Buonaccorso. Exh. cat. San Diego: Timken Museum of Art, 1997., 34–35, fig. 25. ↩︎