Cesare Canessa (1863–1922) and Ercole Canessa (1868–1929) Collection, New York and Paris; sale, American Art Galleries, New York, January 25–26, 1924, lot 152; Maitland Fuller Griggs (1872–1943), New York, 1924

The panel support, of a horizontal wood grain, is 2.0 centimeters thick and has not been thinned or cradled. It shows no signs of the attachment of vertical battens at the back, but it retains fragments of old claw nails 3 centimeters from the top and 4 centimeters from the bottom of the right edge; no nails are in evidence at the left edge. A split running on a slight diagonal with the grain extends from the left edge, passing through the figure of Saint Francis at the level of his shoulders and interrupting his raised left hand, ending in the compartment with the mourning Virgin at a level slightly above her gesturing right hand. Paint loss along this split chiefly affects the figure of Saint Francis and the decorative pattern at the left end of the predella. Examination during cleaning at the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, in 1999–2001 concluded that the dentil pattern running the length of the panel across its top is original; the engaged dentils were not recreated but the green background was restored, leaving negative spaces to suggest their regular placement. The same restoration concluded that barbs of gesso at the left and right ends of the predella are original, but this is incorrect. These (and possibly, although not certainly, the barb at the bottom as well) are remnants of a pre-1924 restoration that incorporated the predella into a modern engaged frame: they run across and fill the split in the panel at the left but are not affected by the movement of the wood there. That frame was removed in a radical cleaning at Yale in 1969; the present frame was designed and built for the panel at the Getty in 2001.

A large area of total loss affects the lower third of the central compartment, from Christ’s thighs down, and extends into the decorative compartment alongside it at the left (fig. 1). The lower-right quadrant of that compartment is a modern reconstruction from the Getty cleaning, as is the green framing strip separating it from the Crucifixion. The lost area in the Crucifixion was filled at that time with a “neutral” colored tratteggio, creating the illogical appearance of damage occurring “behind” the fictive moldings. All the gilt backgrounds and haloes in the figurated compartments are modern, possibly applied in the pre-1924 restoration, but the silver gilding in the decorative fields, while damaged, is largely original; the half-panels at either end are more extensively damaged than the complete panels dividing the figurated compartments. Abrasion and flaking losses are scattered throughout the panel along the interfaces of paint surfaces with the new areas of gilding, and the green “moldings” framing each compartment are much restored. The haloes, where they project beyond the borders of their gilded compartments, are raised slightly above the level of the green painted surrounds. It is not clear if that reflects the original appearance of the predella and was once better resolved, perhaps with pastiglia rims along the top arcs of the haloes, or if it is a clumsy by-product of the later gilding.

The attribution to Luca di Tommè and the identity of the figures in this predella have not been in doubt since it was first brought to the attention of scholars by F. Mason Perkins in 1924, following its appearance with a generic ascription to the school of Simone Martini at the sale of the Ercole Canessa collection earlier that year.1 An expertise written by Richard Offner for Maitland Griggs in February 1924 described the “course of grave and noble mourners of Christ [that] has the hush about it of great tragic moments” and offered comparison to a signed and dated (1367) polyptych by Luca di Tommè in the Pinacoteca in Siena, “if one should require the unnecessary proof that this predella is an absolutely unquestionable work of the master.”2 The few authors who have troubled to consider its dating are divided in their opinions between those who find it an early, “Lorenzettian” work3 and those who prefer to place it in the artist’s maturity.4

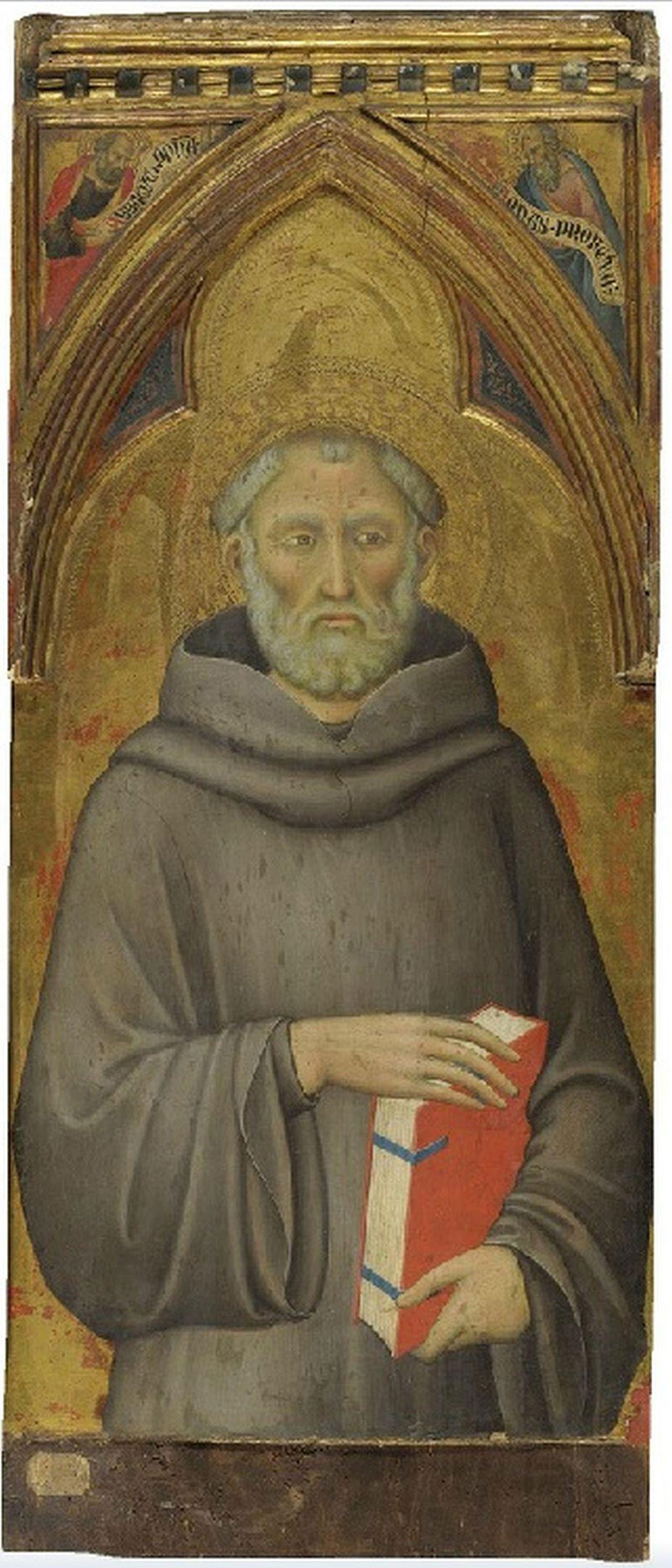

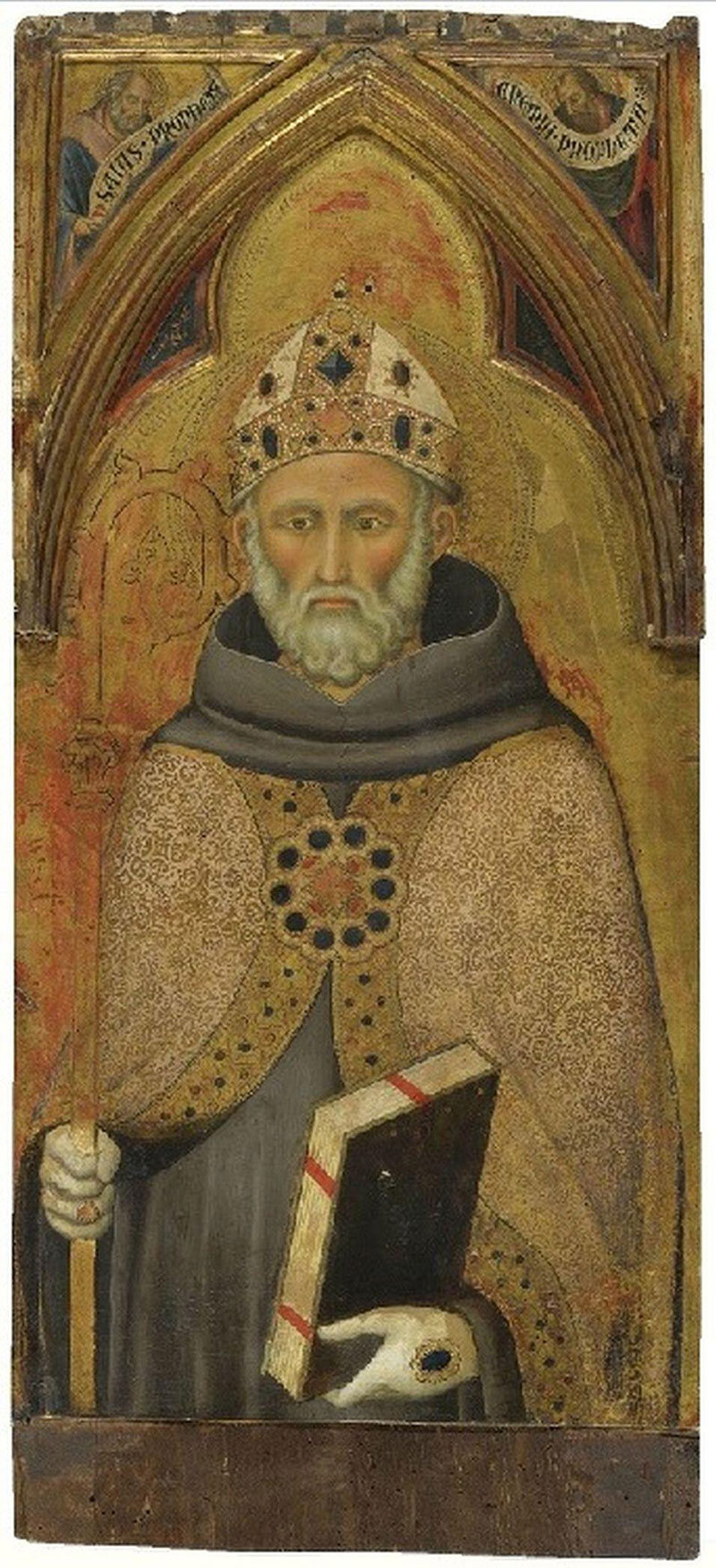

In 1978 Federico Zeri wrote to Andrea Norris, then assistant to the director at the Yale University Art Gallery, reporting that he had found four panels from the main register and two pinnacles from the altarpiece to which he believed the Yale predella belonged, but that he was awaiting further evidence to support the connection. The basis of Zeri’s reconstruction, according to his letter, was in part “that absolutely identical dentils, like those which have been removed from your painting, appear in five of the panels of the altarpiece, and they are unquestionably genuine.”5 It seems that his hesitation was occasioned by uncertainty over the attribution of the other six panels, as it was only through the Yale predella that they could be linked to Luca di Tommè. The panels in question comprise four half-length saints from the main register of the altarpiece: Saint John Gualbert, formerly in the Chalandon collection (fig. 2)6; Saint Michael, in the Alana Collection, Newark, Delaware (fig. 3); Saint John the Baptist, in the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles (fig. 4); and Saint Bernard degli Uberti, formerly in the Chalandon collection (fig. 5),7 reading left to right according the reconstruction proposed by Gaudenz Freuler.8 Among the pinnacles, Zeri identified a panel showing two apostles in the Fondazione Roberto Longhi, Florence (fig. 6), and a Blessing Redeemer in the Kress Collection at the North Carolina Museum of Art, Raleigh (fig. 7).9 To these has since been added a third pinnacle panel, showing Saints Peter and Paul, that appeared at auction in 1989 (fig. 8).10

Only three of these panels—those at the Getty, in Raleigh, and at the Fondazione Roberto Longhi—had been known to Sherwood Fehm, who rejected the attribution of all three to Luca di Tommè, notwithstanding Longhi’s proposal of that artist’s name for the pinnacle in his collection.11 S. D’Argenio, writing in the catalogue of the Fondazione Longhi collection,12 accepted both Zeri’s reconstruction and the attribution for all the panels to Luca di Tommè, as did Giulietta Chelazzi Dini.13 Gaudenz Freuler, investigating a likely provenance for this reconstructed altarpiece from the Vallombrosan church of San Michele in Siena, also accepted the attribution to Luca di Tommè but rejected the Yale predella on the grounds that the inclusion of Saints Francis and Dominic would have been inappropriate for a Vallombrosan commission.14 He proposed instead identifying four narrative panels—a Nativity now in the Alana Collection, an Adoration of the Magi in the Thyssen Collection in Madrid,15 a Crucifixion in the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco,16 and a Presentation in the Temple in a private collection—as parts of the probable predella to this altarpiece, adducing the evidence of size, style, and iconography to bolster his argument. Pia Palladino rejected Freuler’s hypothesis, pointing out that, while he had correctly dated the predella panels shortly before the monumental altarpiece of 1362 that Luca produced in collaboration with Niccolò di Ser Sozzo, the remaining panels from the Vallombrosan altarpiece had to be significantly, possibly as much as a decade, earlier still, certainly predating the Gabella cover of 1357 that was then a recent addition to the study of Luca di Tommè’s stylistic development.17 It should be noted that the four predella panels in question do not actually correspond in size with the panels from the main register of the Vallombrosan altarpiece, as Freuler had claimed, each being on average between 7 and 10 centimeters narrower.

While Palladino also considered the association of the Yale predella with the Vallombrosan altarpiece unconvincing “on both stylistic and technical grounds,” it must be admitted that the stylistic evidence available at the time was compromised by the drastically abraded state of the predella at that time.18 Technical evidence, in the form of punch tooling, had also been misrepresented. Erling Skaug described the punch tools decorating gilded haloes and borders in the Yale predella, which he acknowledged knowing only through photographs provided to him by Norman Muller, as an unicum within the career of Luca di Tommè.19 Mojmír Frinta later classified these punch tools as restorations, and it is indeed true that the gold backgrounds in all five figurated sections of the predella are modern.20 Furthermore, the predella is a fragment, as seems to have been observed so far only by Palladino. The decorative panels of blue and red sgraffito ornament against a silver ground that divide each of the figurated compartments are not meant to be read as positive elements in the overall composition: the truncated panels at either end must originally have been full squares, not half squares, and undoubtedly served to divide both Saints Francis and Dominic from a further compartment with a saint—one of whom is likely to have been Saint Benedict—that closed off the predella at either side. Adding these missing portions back into the overall length of the predella results in a total width commensurate with that of the Vallombrosan altarpiece panels. Specifically, it establishes a proportional relationship of the predella imagery with the panels above it, wherein two saints in the main register stood directly above two saints and the mourning Virgin (left) and above two saints and the mourning Evangelist (right) in the predella, while the missing central panel, almost certainly portraying the Virgin and Child, occupied exactly the same width as the Crucified Christ and its two decorative end panels in the predella, 58.5 centimeters. As Federico Zeri observed, the dentilated molding closing off the predella at the top is identical to that preserved in three of the four panels from the main register as well as in the Fondazione Longhi pinnacle,21 and it should be noted that no similar molding occurs in any other work by Luca di Tommè. Finally, while it is difficult to claim any compelling stylistic relationship between the predella saints and those appearing on a much larger scale in the main register, they are, in fact, all but identical in type and handling to the smaller apostles in the Longhi pinnacle. It is, in short, a viable conclusion that the Yale predella was originally part of the Vallombrosan altarpiece.

The arguments elaborated by Palladino for considering the panels of the Vallombrosan altarpiece among Luca di Tommè’s earliest surviving works, or at least as the earliest of the works commonly accepted as being by him, are completely convincing, as is her proposal for situating them in the first half of the decade of the 1350s. Citing the evidence of shared punch tools (not in reference to the Yale panel) and stylistic rapprochement, furthermore, she suggests that these panels may also indicate an earlier period of collaboration between Luca di Tommè and Niccolò di Ser Sozzo, independent of their work together on the 1362 Umiliati altarpiece in Siena. A logical corollary of this contention may well be that the missing central panel of the Vallombrosan altarpiece is to be sought not among the recognizable works of Luca di Tommè but among those of Niccolò di Ser Sozzo, an avenue of investigation that has not yet been explored. —LK

Published References

Illustrated Catalogue of the Ercole Canessa Collection. New York: American Art Galleries, 1924., no. 152; Perkins, F. Mason. “Altre pittura di Luca di Tommè.” Rassegna d’arte senese 18, nos. 1–2 (March 1924): 15., 15n; Comstock, Helen. “Luca di Tommè in American Collections.” International Studio 89, no. 368 (January 1928): 57–62., 58–59; Perkins, F. Mason. “Luca di Tommè.” In Allgemeines Lexikon der bildenden Künstler: Von der Antike bis zur Gegenwart, ed. Ulrich Thieme and Felix Becker. Leipzig, Germany: E. A. Seemann, 1929., 427; van Marle, Raimond. “Ancora quadri senesi.” La Diana 6, no. 3 (1931): 168–76., 170, pl. 5; Berenson, Bernard. Italian Pictures of the Renaissance: A List of the Principal Artists and Their Works with an Index of Places. Oxford: Clarendon, 1932., 313; Berenson, Bernard. Pitture italiane del Rinascimento: Catalogo dei principali artisti e delle loro opera. Trans. Emilio Cecchi. Milan: Ulrico Hoepli, 1936., 269; Frankfurter, Alfred M. “The Maitland F. Griggs Collection.” Art News 35, no. 31 (May 1, 1937): 29–46., 156; Berenson, Bernard. Italian Pictures of the Renaissance, A List of the Principal Artists and Their Works with an Index of Places: Central Italian and North Italian Schools. 3 vols. London: Phaidon, 1968., 1:225; Seymour, Charles, Jr. Early Italian Paintings in the Yale University Art Gallery. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1970., 81, 311, no. 54; Fredericksen, Burton B., and Federico Zeri. Census of Pre-Nineteenth-Century Italian Paintings in North American Public Collections. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1972., 600; Vertova, Luisa. “The New Yale Catalogue.” Burlington Magazine 115 (March 1973): 159–61, 163., 159–60; Fehm, Sherwood A., Jr. The Collaboration of Niccolò Tegliacci and Luca di Tommè. J. Paul Getty Museum Publications 5. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 1973., 15, 31n31; Muller, Norman E. “Observations on the Painting Technique of Luca di Tommè.” Los Angeles County Museum of Art Bulletin 19, no. 2 (1973): 12–21., 16, 18, 21n33, fig. 8; De Benedictis, Cristina. La pittura senese, 1330–1370. Florence: Salimbeni, 1979., 88; Chelazzi Dini, Giulietta, ed. Il gotico a Siena: Miniature, pitture, oreficerie, oggetti d’arte. Florence: Centro Di, 1982., 278; Fehm, Sherwood A., Jr. Luca di Tommè: A Sienese Fourteenth-Century Painter. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 1986., 95–96, no. 20; Skaug, Erling S. Punch Marks from Giotto to Fra Angelico: Attribution, Chronology, and Workshop Relationships in Tuscan Panel Painting, with Particular Consideration to Florence, c. 1330–1430. 2 vols. Oslo: International Institute for Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works—Nordic Group, 1994., 1:244; Freuler, Gaudenz. “L’eredità di Pietro Lorenzetti verso il 1350: Novità per Biagio di Goro, Niccolo di Sozzo e Luca di Tommè.” Nuovi studi 4, no. 2 (1997): 15–32., 24; Palladino, Pia. Art and Devotion in Siena after 1350: Luca di Tommè and Niccolò di Buonaccorso. Exh. cat. San Diego: Timken Museum of Art, 1997., 76n72; Frinta, Mojmír S. Punched Decoration on Late Medieval Panel and Miniature Painting. Vol. 1, Catalogue Raisonné of All Punch Shapes. Prague: Maxdorf, 1998., 449; Leonard, Mark. “Artist/Conservator Materials: The Restoration of a Predella Panel by Luca di Tommé [sic].” In Early Italian Paintings: Approaches to Conservation; Proceedings of a Symposium at the Yale University Art Gallery, April 2002, ed. Patricia Sherwin Garland, 225–32. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 2003., 164, 225–32, pls. 40–42, figs. 14.1–.4

Notes

-

Perkins, F. Mason. “Altre pittura di Luca di Tommè.” Rassegna d’arte senese 18, nos. 1–2 (March 1924): 15., 15n. ↩︎

-

Richard Offfner, expertise. ↩︎

-

van Marle, Raimond. “Ancora quadri senesi.” La Diana 6, no. 3 (1931): 168–76., 170, pl. 5; Frankfurter, Alfred M. “The Maitland F. Griggs Collection.” Art News 35, no. 31 (May 1, 1937): 29–46., 156; Fredericksen, Burton B., and Federico Zeri. Census of Pre-Nineteenth-Century Italian Paintings in North American Public Collections. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1972., 600; Fehm, Sherwood A., Jr. The Collaboration of Niccolò Tegliacci and Luca di Tommè. J. Paul Getty Museum Publications 5. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 1973., 15, 31n31; Chelazzi Dini, Giulietta, ed. Il gotico a Siena: Miniature, pitture, oreficerie, oggetti d’arte. Florence: Centro Di, 1982., 278; and Fehm, Sherwood A., Jr. Luca di Tommè: A Sienese Fourteenth-Century Painter. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 1986., 95–96, no. 20. ↩︎

-

Perkins, F. Mason. “Altre pittura di Luca di Tommè.” Rassegna d’arte senese 18, nos. 1–2 (March 1924): 15., 15n; Perkins, F. Mason. “Luca di Tommè.” In Allgemeines Lexikon der bildenden Künstler: Von der Antike bis zur Gegenwart, ed. Ulrich Thieme and Felix Becker. Leipzig, Germany: E. A. Seemann, 1929., 427; and Seymour, Charles, Jr. Early Italian Paintings in the Yale University Art Gallery. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1970., 81, no. 54. ↩︎

-

Federico Zeri, letter to Andrea Norris, curatorial files, Department of European Art, Yale University Art Gallery. ↩︎

-

Sale, Sotheby’s, London, July 8, 2009, lot 22. ↩︎

-

Sale, Sotheby’s, London, July 8, 2009, lot 21. ↩︎

-

Freuler, Gaudenz. “L’eredità di Pietro Lorenzetti verso il 1350: Novità per Biagio di Goro, Niccolo di Sozzo e Luca di Tommè.” Nuovi studi 4, no. 2 (1997): 15–32., 24. ↩︎

-

Federico Zeri, in Fredericksen, Burton B., and Federico Zeri. Census of Pre-Nineteenth-Century Italian Paintings in North American Public Collections. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1972.. ↩︎

-

Sale, Finarte, Milan, December 13, 1989, lot 137. ↩︎

-

Fehm, Sherwood A., Jr. The Collaboration of Niccolò Tegliacci and Luca di Tommè. J. Paul Getty Museum Publications 5. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 1973., 15, 31n31. ↩︎

-

S. D’Argenio, in La Fondazione Roberto Longhi a Firenze. Milan: Electa, 1980., 242. ↩︎

-

Chelazzi Dini, Giulietta, ed. Il gotico a Siena: Miniature, pitture, oreficerie, oggetti d’arte. Florence: Centro Di, 1982., 278. ↩︎

-

Freuler, Gaudenz. “L’eredità di Pietro Lorenzetti verso il 1350: Novità per Biagio di Goro, Niccolo di Sozzo e Luca di Tommè.” Nuovi studi 4, no. 2 (1997): 15–32., 24. ↩︎

-

Inv. no. 1978.46. ↩︎

-

Inv. no. 66.41.3. ↩︎

-

Palladino, Pia. Art and Devotion in Siena after 1350: Luca di Tommè and Niccolò di Buonaccorso. Exh. cat. San Diego: Timken Museum of Art, 1997., 76n72. ↩︎

-

Palladino, Pia. Art and Devotion in Siena after 1350: Luca di Tommè and Niccolò di Buonaccorso. Exh. cat. San Diego: Timken Museum of Art, 1997., 76n72 ↩︎

-

Skaug, Erling S. Punch Marks from Giotto to Fra Angelico: Attribution, Chronology, and Workshop Relationships in Tuscan Panel Painting, with Particular Consideration to Florence, c. 1330–1430. 2 vols. Oslo: International Institute for Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works—Nordic Group, 1994., 1:244. ↩︎

-

Frinta, Mojmír S. Punched Decoration on Late Medieval Panel and Miniature Painting. Vol. 1, Catalogue Raisonné of All Punch Shapes. Prague: Maxdorf, 1998., 449. Frinta listed four other paintings employing the same punch tools in restorations, including the Adoration of the Shepherds altarpiece fragment by Bartolomeo Bulgarini at the Fogg Museum, Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass. (inv. no. 1917.89, not the Museum of Fine Arts [MFA], Boston, as he recorded), a Virgin and Child attributed to Lippo Memmi at the MFA (inv. no. 36.114), and a full-length Saint Lucy now recognized as the work of Jacopo del Casentino (sale, Christie’s, New York, April 15, 2008, lot 4). The painting at the MFA has been identified by Gianni Mazzoni (Mazzoni, Gianni. Quadri antichi del novecento. Vicenza: Neri Pozza, 2001., 308–12) as the work of Icilio Federico Joni. It is unclear whether the painting is entirely an invention of Joni or one of the many severely damaged early paintings extensively “restored” by him, but it might be possible to conclude that Joni was responsible for regilding all the paintings in the group listed by Frinta, including the Yale predella. ↩︎

-

Federico Zeri, in Fredericksen, Burton B., and Federico Zeri. Census of Pre-Nineteenth-Century Italian Paintings in North American Public Collections. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1972.. ↩︎