Dan Fellows Platt(?) (1873–1937), Englewood, N.J.;1 Durlacher Brothers, London and New York, by 1920;2 Maitland Fuller Griggs (1872–1943), New York, by February 25, 1924

The panel, of a vertical grain, retains its original thickness of 1.9 centimeters. It is comprised of three planks, 9.5, 41.7, and 8.7 centimeters wide, left to right; several prominent knots occur in the central plank. The reverse is discolored from the removal of an 8-centimeter-wide batten, 40 centimeters (on center) from the present bottom edge of the panel. A dowel peg on the right edge of the panel, 1.2 centimeters in diameter, is inserted 33.8 centimeters from the bottom, or 1.5 centimeters below the level of the batten. A similar dowel on the left edge is inserted 35 centimeters from the bottom, or 5 millimeters below the batten. The join between the center and left planks has opened and was further excavated by Andrew Petryn in a drastic cleaning of 1959 to expose wood, linen, and gesso along its full length. The join between the center and right planks has produced three irregular vertical splits in the paint surface but no significant loss of pigment. The pastiglia moldings defining the arch at the top of the panel are broken and partially lost.

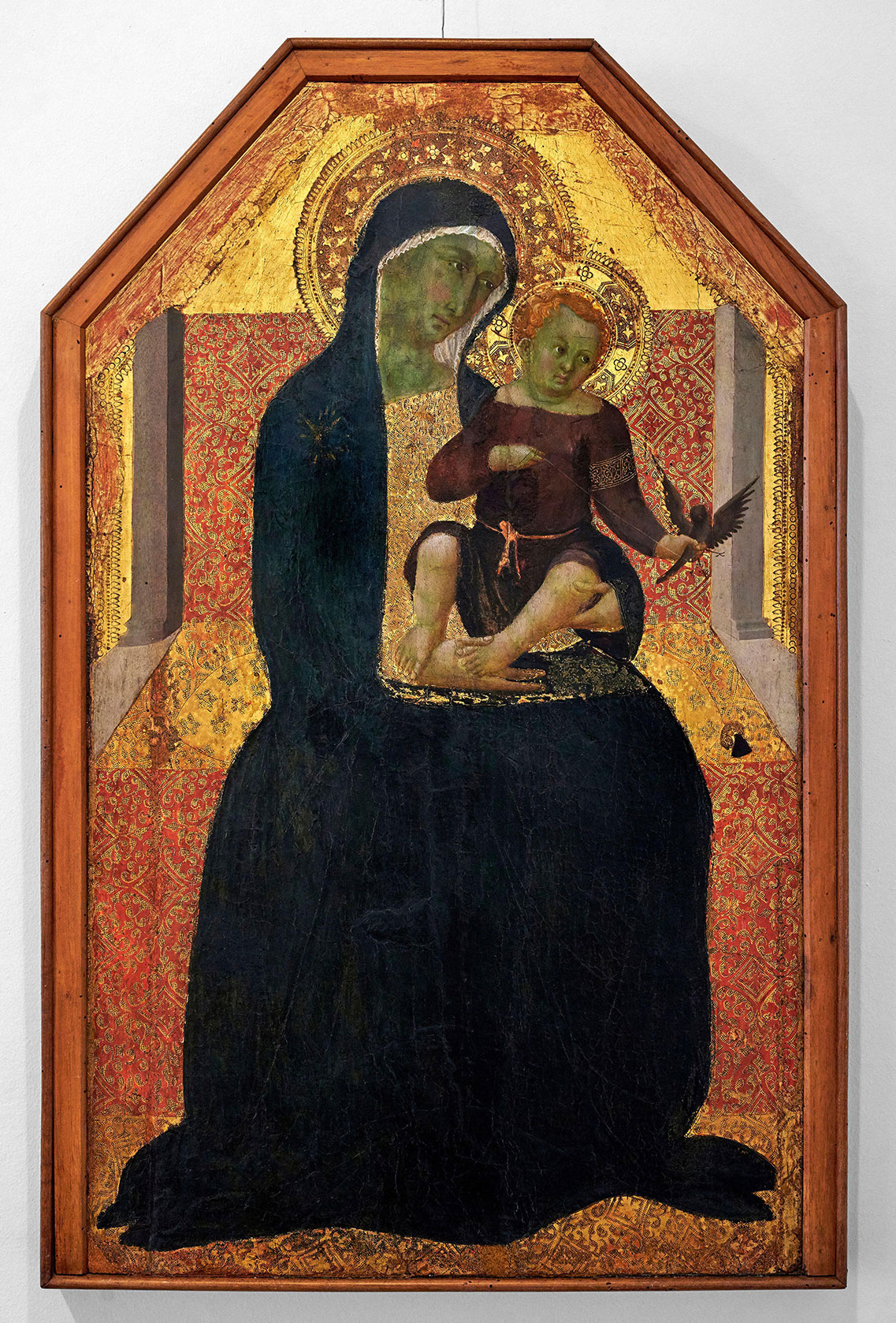

The gold ground is heavily abraded, the haloes less so except that dirt within the punch impressions in the Christ Child’s halo and in the lower half of the Virgin’s halo was aggressively removed with solvents that destroyed gilding as well and exposed a damaged gesso underlayer. The paint surface has been badly burned by solvents and is heavily abraded. Flesh tones remain visible only in the figures’ hands. The Virgin’s robe has been severely damaged and was scraped down to the wood in areas of her lap and cowl. Her red dress and the red-and-blue cloth of honor are scarred by numerous small local losses exposing the gesso preparation beneath. The Virgin’s white veil and the Child’s yellow and purple garments retain more of their original modeling. The silver and blue sgraffito decoration within the cusps lining the arch is abraded, while that in the spandrels outside the main arch is relatively well preserved. A 1.4-centimeter-wide strip of polished gesso along the right edge of the panel is original and was meant to be covered by an attached pilaster; a corresponding strip on the left side has been badly pitted and scored by solvents.

This panel, already drastically reduced in height when it first appeared on the art market around 1920, was originally the center of a large polyptych with the Virgin and Child Enthroned, flanked by standing saints. As evidenced by comparisons with early photographs (fig. 1), the painted surface was still relatively intact before being irreparably damaged in a 1959 cleaning. The earliest record of the work is an expert opinion written by F. Mason Perkins for the London and New York firm of Durlacher Brothers, in April 1920, excerpts of which are preserved in the Frick Art Reference Library, New York, and in the Yale curatorial files.3 In it the scholar referred to the image as “a most interesting and rare find” and attributed it to the author of a Nativity in the Fogg Art Museum, Cambridge, Massachusetts, christened by him “Master of the Fogg Museum Nativity.”4 As Perkins reported in another letter, his attribution had been confirmed by Bernard Berenson, who had already gathered a body of works around the Fogg Nativity under the fictitious sobriquet “Ugolino Lorenzetti,” in reference to the peculiar blend of derivations from Ugolino di Nerio and Pietro Lorenzetti. In 1923 Ernest DeWald5 inserted the Virgin and Child, then with the New York branch of Durlacher, in his reconstruction of the so-called Ovile Master—named after a Virgin and Child in the church of San Pietro Ovile, Siena (now Museo Diocesano d’Arte Sacra )—whose oeuvre comprised some of the paintings assigned by Berenson to “Ugolino Lorenzetti,” including the Fogg Nativity. Calling the present panel “an excellent example of the Ovile Master’s work,” DeWald evoked the coloristic brilliance that characterized the image, noting “the lovely vermillion brocade” of the cloth of honor behind the Virgin; “the lovely blue” of the Virgin’s mantle; and “the strong yellow” of the drapery of the Christ Child, which recalled the color effects of the Fogg Nativity. The painting was in the collection of Maitland Griggs by February 25, 1924, when Richard Offner described it as “an undisputable and typical” work of the Ovile Master in a Lorenzettesque phase,” pointing out that the painted surface was “slightly worn, but free from any disfiguring damage or restoration.”6 The attribution to the Ovile Master was reiterated in Venturi’s 1931 overview of Italian paintings in American collections, which provides the most detailed record of the painting’s original palette: “The gold background is nearly covered by the great red and gold cloth of the throne. The Madonna wears a blue cloak and red robe, the Child a lilac cloak and yellow robe, and the angels are in blue, red and gold. The flesh tints are dark blonde. There are some signs of toning.”7

In two fundamental studies in the 1930s,8 Millard Meiss convincingly demonstrated that the two groups of works alternatingly assigned to “Ugolino Lorenzetti” and the Ovile Master reflected different phases in the career of the same painter, identified as Bartolomeo Bulgarini. Meiss’s proposal, based on circumstantial evidence and the realization that the same hand was responsible for a biccherna cover for which Bartolomeo was paid in 1353, was not immediately embraced by scholars. Berenson continued to list the Yale Virgin and Child under “Ugolino Lorenzetti,” while Seymour catalogued it under “Master of the Ovile Madonna (‘Ugolino Lorenzetti’),” with a date around 1340.9 Most doubts were dispersed, however, with the subsequent discovery of documentary proof that the Fogg Nativity—central to the “Ugolino Lorenzetti”/Ovile Master debate—was, in fact, the main panel of an altarpiece painted by Bartolomeo Bulgarini between around 1348 and 1351 for the chapel of Saint Victor in Siena Cathedral.10

In her monographic study of Bartolomeo Bulgarini, Judith Steinhoff reexamined the Yale Virgin and Child, confirming the hypothesis, first formulated by Berenson and picked up by Seymour,11 that it was originally flanked by the four standing saints unanimously attributed to the artist in the Museo Nazionale di San Matteo, Pisa: Saint Lucy, Saint Michael the Archangel, Saint Bartholomew, and Saint Catherine of Alexandria (figs. 2–3). As demonstrated by Steinhoff and supported by recent examination, the relationship between the Pisa Saints and the Yale Virgin and Child is confirmed, as much as by stylistic comparisons, by shared framing elements and structural details. Like the Yale Virgin, the standing figures are enclosed by the same five-lobed arch, with identical silver patterns in the spaces between the raised cusps and in the spandrels. The panels, which have the same thickness, were formerly attached by horizontal battens, still present on the top and bottom of the Pisa Saints. Traces of the missing upper batten are still visible on the reverse of the Yale Virgin, and dowel holes on both sides align with those in two of the Pisa panels: on the left, with Saint Michael, and on the right, with Saint Bartholomew. The two female saints occupied the extremities of the altarpiece, Lucy on the left and Catherine of Alexandria on the right.12

The Pisa panels were formerly part of the collection of Canon Sebastiano Zucchetti (1723–1801), deacon of Pisa Cathedral between 1784 and 1801, suggesting a Pisan provenance for the original complex.13 Most recently, Linda Pisani advanced the possibility that Bulgarini’s altarpiece, which shows Saint Michael in the position of honor to the Virgin’s right and also includes Catherine of Alexandria, could have been executed for the chapel of Saint Michael in the Dominican convent of Santa Caterina in Pisa.14 According to a description of the church of Santa Caterina compiled by the Pisan canon Ranieri Zucchelli around 1787, the chapel had been founded sometime before 1340 by the powerful Della Rocca family and was the site of a family tomb.15 Bolstering Pisani’s proposition is her plausible suggestion that two small tondi by Bulgarini recently on the art market, showing Saint Dominic and Saint Peter Martyr and stylistically related to the Yale/Pisa panels (figs. 4–5), could be additional fragments of the same altarpiece, possibly inserted into the now-missing upper framing elements.16 Pisani tentatively placed the execution of the polyptych around 1355, when the probable founder of the chapel of Saint Michael, Dino Della Rocca (documented 1322–55), banned from the city in 1347 for his role in a plot to assassinate Count Ranieri Novello, returned from exile along with other members of the family.17

While not conclusive, the circumstantial evidence presented by Pisani coincides with the chronology of the Yale/Pisa altarpiece advanced by past authors on stylistic grounds. Most modern scholarship has concurred in dating the complex after the San Gimignano Polyptych in the Salini Collection, Asciano, datable on internal evidence between 1353 and 1355.18 Steinhoff initially placed the Yale/Pisa altarpiece in the mid- to late 1350s but later proposed a more specific date around 1356,19 immediately following the execution of a polyptych from the Hospital Church of Santa Maria della Scala in Siena.20 As noted by other critics, however, the absence of any dated paintings in Bulgarini’s oeuvre, apart from small-scale biccherna covers, makes it difficult to establish a precise chronological sequence of works. Both the Hospital polyptych and the Yale/Pisa altarpiece may be inserted among a group of images that document the increasingly decorative concerns and softening of the forms in Bulgarini’s production through the second half of the 1350s—possibly under the influence of a new awareness of Simonesque models—but do not yet achieve the precious quality of the Ovile Madonna, or the much later Assumption of the Virgin from Santa Maria della Scala.21 In its simplicity of design and looser execution, the Yale Virgin bears an especially close relationship to the Enthroned Virgin and Child in the Museo d’Arte Sacra in Grosseto, painted by the artist for Grosseto Cathedral or a church in its environs (fig. 6).22 Comparisons may also be drawn between the Pisa Saints and the small figures in the tabernacle presently divided between the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston,23 and the Philadelphia Museum of Art24—a work possibly associated with another Pisan commission.25 Alongside the Yale/Pisa altarpiece, these paintings may document a particular moment in Bulgarini’s career, between 1355 and 1360, when he was actively engaged in projects outside his native city. —PP

Published References

DeWald, Ernest. “The Master of the Ovile Madonna.” Art Studies 1 (1923): 45–54., 52–53, fig. 33; van Marle, Raimond. The Development of the Italian Schools of Painting. Vol. 5. The Hague: M. Nijhoff, 1925., 458; Péter, Andrea. “Un lorenzettiano: Il ‘Maestro della Madonna d’Ovile.’” La Balzana, no. 2 (1927): 93., 93; DeWald, Ernest. “Pietro Lorenzetti.” Art Studies: Medieval, Renaissance, and Modern 7 (1929): 131–66., 155; DeWald, Ernest. Pietro Lorenzetti. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1930., 27–28; Meiss, Millard. “Ugolino Lorenzetti.” Art Bulletin 13, no. 3 (September 1931): 376–97., 376n2, 379n4, 383n9, 384n14; Venturi, Lionello. Pitture italiane in America. 2 vols. Milan: Ulrico Hoepli, 1931., pl. 71; Berenson, Bernard. Italian Pictures of the Renaissance: A List of the Principal Artists and Their Works with an Index of Places. Oxford: Clarendon, 1932., 295; Venturi, Lionello. Italian Paintings in America. Trans. Countess Vanden Heuvel and Charles Marriott. 3 vols. New York: E. Weyhe, 1933., pl. 88; Berenson, Bernard. Pitture italiane del Rinascimento: Catalogo dei principali artisti e delle loro opera. Trans. Emilio Cecchi. Milan: Ulrico Hoepli, 1936., 253; Shorr, Dorothy C. The Christ Child in Devotional Images in Italy during the XIV Century. New York: George Wittenborn, 1954., 159, fig. 24 Siena 4; Shapley, Fern Rusk. Paintings from the Samuel H. Kress Collection: Italian Schools, XIII–XV Century. London: Phaidon, 1966., 54–55n3; Berenson, Bernard. Italian Pictures of the Renaissance, A List of the Principal Artists and Their Works with an Index of Places: Central Italian and North Italian Schools. 3 vols. London: Phaidon, 1968., 1:435; Seymour, Charles, Jr. Early Italian Paintings in the Yale University Art Gallery. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1970., 86–87, 311, no. 61; Fredericksen, Burton B., and Federico Zeri. Census of Pre-Nineteenth-Century Italian Paintings in North American Public Collections. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1972., 133, 600; Charles Seymour, Jr., in Seymour, Charles, Jr., et al. Italian Primitives: The Case History of a Collection and Its Conservation. Exh. cat. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1972., 8; De Benedictis, Cristina. La pittura senese, 1330–1370. Florence: Salimbeni, 1979., 85; Skaug, Erling S. “Punch Marks—What Are They Worth? Problems of Tuscan Workshop Interrelationships in the Mid-14th Century: The Ovile Master and Giovanni da Milano.” In La pittura nel XIV e XV secolo: Il contributo dell’analisi tecnica alla storia dell’arte, ed. Henk van Os and J. van Asperen de Boer, 25–82. International Congress of the History of Art 3. Bologna: CLUEB, 1982., 263; Steinhoff, Judith. “Bartolomeo Bulgarini and Sienese Painting of the Mid-Fourteenth Century.” Ph.D. diss., Princeton University, 1990., 126–27, 471, 493–509, 562–63, 566, 575, nos. 31–32; Steinhoff, Judith. “A Trecento Altarpiece Rediscovered: Bartolommeo Bulgarini’s Polyptych for San Gimignano.” Zeitschrift für Kunstgeschichte 56 (1993): 102–12., 11; Skaug, Erling S. Punch Marks from Giotto to Fra Angelico: Attribution, Chronology, and Workshop Relationships in Tuscan Panel Painting, with Particular Consideration to Florence, c. 1330–1430. 2 vols. Oslo: International Institute for Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works—Nordic Group, 1994., 1:25, 253; Strehlke, Carl Brandon. Italian Paintings, 1250–1450, in the John G. Johnson Collection and the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Philadelphia: Philadelphia Museum of Art, 2004., 89n8; Steinhoff, Judith. Sienese Painting after the Black Death: Artistic Pluralism, Politics, and the New Art Market. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006., 91, 93–94, fig. 34; Boskovits, Miklós. Italian Paintings of the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries. Washington, D.C.: National Gallery of Art, 2016. NGA Online Editions, https://purl.org/nga/collection/catalogue/italian-paintings-of-the-thirteenth-and-fourteenth-centuries., 26; Pisani, Linda. Francesco Traini e la pittura a Pisa nella prima metà del trecento. Cinisello Balsamo, Milan: Silvana, 2020., 254–55

Notes

-

According to Charles Seymour, Jr., in Seymour, Charles, Jr., et al. Italian Primitives: The Case History of a Collection and Its Conservation. Exh. cat. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1972., 8. Seymour notes the possibility that this work might be no. 166 in the Platt Collection. The present author has not been able to confirm this information, reportedly obtained from unpublished records in Mrs. Platt’s files, provided to Seymour by John H. W. Clark. ↩︎

-

An early photograph of the painting in the Fototeca Zeri, Federico Zeri Foundation, Bologna, bears the stamp of the British fine art photographer William Edward Gray (1864–1935), who had a studio at 92 Queen’s Road, Bayswater, London, suggesting that the work was in England at an unknown date. Among Gray’s activities, beginning in the 1890s, was photographing works of art in country houses, so their owners could showcase their collections; see Gray’s correspondence in the Pitt Rivers Museum, Oxford, “Salisbury & South Wiltshire Museum Catalogue of the Letters of Augustus Henry Lane Fox Pitt-Rivers,” http://web.prm.ox.ac.uk/sswm/sswm_letters/SSWM_RPR_B481.pdf. Gray’s photographs were also used by English dealers and their agents to promote the sale of works of art. See below. ↩︎

-

The excerpts in the Frick accompany another print of the same photograph in the Zeri archives (see note 2, above), courtesy of “Messr. Durlacher.” Shorter excerpts of Perkins’s letters were forwarded by Adam E. Merriman Paff of Durlacher to Maitland Griggs on November 26, 1923, in answer to the latter’s request for an expert opinion, possibly prior to his purchase. ↩︎

-

Inv. no. 1917.89, https://harvardartmuseums.org/collections/object/232007?position=232007. ↩︎

-

DeWald, Ernest. “The Master of the Ovile Madonna.” Art Studies 1 (1923): 45–54., 52. ↩︎

-

Richard Offner, expert opinion, recorded in the curatorial files, Department of European Art, Yale University Art Gallery. ↩︎

-

Venturi, Lionello. Pitture italiane in America. 2 vols. Milan: Ulrico Hoepli, 1931., pl. 71. ↩︎

-

Meiss, Millard. “Ugolino Lorenzetti.” Art Bulletin 13, no. 3 (September 1931): 376–97., 376–97; and Meiss, Millard. “Bartolommeo Bulgarini altrimenti detto ‘Ugolino Lorenzetti?’” Rivista d’arte 18 (1936): 113–36., 113–36. ↩︎

-

Berenson, Bernard. Italian Pictures of the Renaissance: A List of the Principal Artists and Their Works with an Index of Places. Oxford: Clarendon, 1932., 295; Berenson, Bernard. Italian Pictures of the Renaissance, A List of the Principal Artists and Their Works with an Index of Places: Central Italian and North Italian Schools. 3 vols. London: Phaidon, 1968., 1:435; and Seymour, Charles, Jr. Early Italian Paintings in the Yale University Art Gallery. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1970., 86–87, no. 61. ↩︎

-

Beatson, Elizabeth H., Norman E. Muller, and Judith B. Steinhoff. “The St. Victor Altarpiece in Siena Cathedral: A Reconstruction.” Art Bulletin 68, no. 4 (December 1986): 610–31., 610–63. A 1351 document recording payment for the final decorative framing elements of the Saint Victor altarpiece provides a secure terminus ante quem for its execution. ↩︎

-

Steinhoff, Judith. “Bartolomeo Bulgarini and Sienese Painting of the Mid-Fourteenth Century.” Ph.D. diss., Princeton University, 1990., 126–27, 471, 493–509, 562–63, 566, 575, nos. 31–32; Berenson, Bernard. Italian Pictures of the Renaissance, A List of the Principal Artists and Their Works with an Index of Places: Central Italian and North Italian Schools. 3 vols. London: Phaidon, 1968., 1:435–36; and Seymour, Charles, Jr. Early Italian Paintings in the Yale University Art Gallery. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1970., 86–87, no. 61. ↩︎

-

Based on the distance between the top batten and the base of the Pisa Saints (90 cm), it can be estimated that around 54.5 centimeters are missing from the bottom of the Yale panel. The present author is very grateful to Pierluigi Nieri of the Museo Nazionale di San Matteo for sharing measurements and photographs of the reverse of the Pisa panels. ↩︎

-

Burresi, Mariagiulia, and Antonino Caleca. “Il decano Sebastiano Zucchetti e la sua collezione di ‘primitivi.’” In Conoscere, conservare, valorizzare i beni culturali ecclesiastici: Studi in memoria di Monsignor Waldo Dolfi, ed. Ottavio Banti and Gabriella Garzella, 57–68. Ospedaletto, Pisa: Pacini, 2011., 57–68. The paintings were described in Zucchetti’s inventory (nos. 72–75) as “four panels 2 braccia high, the first showing Saint Bartholomew, the second Saint Michael the archangel, the third Saint Catherine virgin and martyr, and the fourth Saint Margaret. Believed to be by Zanobio Macchiavelli” (Quattro quadri alti braccia 2, che il primo rappresenta San Bartolommeo, il 2° San Michele arcangelo, il 3° Santa Caterina vergine e martire, ed il 4° Santa Margherita. Creduti di Zanobio Machiavelli). The figure of Saint Michael the Archangel has sometimes been mistakenly identified as Saint George by modern authors. Judith Steinhoff correctly identified the figure described as Saint Margaret in the inventory (and by others as Saint Agatha) as Saint Lucy. ↩︎

-

Pisani, Linda. Francesco Traini e la pittura a Pisa nella prima metà del trecento. Cinisello Balsamo, Milan: Silvana, 2020., 254–55. ↩︎

-

Cited in Pisani, Linda. Francesco Traini e la pittura a Pisa nella prima metà del trecento. Cinisello Balsamo, Milan: Silvana, 2020., 129. ↩︎

-

Sale, Moretti Fine Art, London, 2016. The two roundels were formerly in the Carlo De Carlo collection, Florence, and before that were on the French art market. They were dated between 1350 and 1355 by Gaudenz Freuler (expert opinion, recorded by Moretti Fine Art). ↩︎

-

Pisani, Linda. Francesco Traini e la pittura a Pisa nella prima metà del trecento. Cinisello Balsamo, Milan: Silvana, 2020., 129–30, notes that a specific connection between Dino Della Rocca and Santa Caterina is evidenced by the dedication to him of an important Pisan manuscript—the illuminated copy of Ranieri Granchi’s De Preelis Tuscie, in the Biblioteca Classense, Ravenna. Written by a Dominican friar in Santa Caterina, the text, most likely produced in the convent’s scriptorium, is an account of the political events and battles of which Dino della Rocca was a protagonist in the years between 1315 and 1347; it also includes a specific reference to him praying and attending private masses in Santa Caterina. See Granchi, Ranieri. De preliis Tuscie. Ed. Michela Diana. Florence: SISMEL, 2008., 31. For Dino Della Rocca, see also Ceccarelli Lemut, Maria Luisa. “Della Rocca, Dino.” Dizionario biografico degli italiani. Rome: Istituto della Enciclopedia Italiana, 1989. https://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/dino-della-rocca_(Dizionario-Biografico)/ (with previous bibliography). ↩︎

-

Steinhoff, Judith. “A Trecento Altarpiece Rediscovered: Bartolommeo Bulgarini’s Polyptych for San Gimignano.” Zeitschrift für Kunstgeschichte 56 (1993): 102–12., 102–12; and Francesco Mori, in Bellosi, Luciano, ed. La collezione Salini: Dipinti, sculture e oreficerie dei secoli XII, XIII, XIV e XV. Vol. 1, Pittura. Florence: Centro Di, 2009., 104–13, no. 10. ↩︎

-

Steinhoff, Judith. Sienese Painting after the Black Death: Artistic Pluralism, Politics, and the New Art Market. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006., 92. ↩︎

-

Now Pinacoteca Nazionale, Siena, inv. no. 76. For the reconstruction of the Hospital altarpiece, see Steinhoff, Judith. “Bartolomeo Bulgarini and Sienese Painting of the Mid-Fourteenth Century.” Ph.D. diss., Princeton University, 1990., 464–76 (with previous bibliography). Based on seventeenth-century sources recording the presence of a painting by Bulgarini on the altar of the chapel of Saint Luke, Steinhoff associated this work with a certain Monna Becca, who in 1355 commissioned Jacopo di Mino del Pellicciaio to fresco that chapel, of which she had held the patronage since 1351. Steinhoff suggested Bulgarini’s painting was commissioned by Monna Becca around the same time as the frescoes, in 1355. For a different opinion and a date around 1350, see Strehlke, Carl Brandon. Italian Paintings, 1250–1450, in the John G. Johnson Collection and the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Philadelphia: Philadelphia Museum of Art, 2004., 88, 89n11. ↩︎

-

Pinacoteca Nazionale, Siena, inv. no. 61. ↩︎

-

The Grosseto panel, badly damaged and cut at the top and sides, may originally have had a round arch set in a rectangular filed, like the Yale Virgin. For a full discussion of its provenance and condition, see Steinhoff, Judith. “Bartolomeo Bulgarini and Sienese Painting of the Mid-Fourteenth Century.” Ph.D. diss., Princeton University, 1990., 487–92, no. 30. ↩︎

-

Inv. no. P15n8, https://www.gardnermuseum.org/experience/collection/10794. ↩︎

-

Inv. no. 92, https://philamuseum.org/collection/object/102757. ↩︎

-

Strehlke, Carl Brandon. Italian Paintings, 1250–1450, in the John G. Johnson Collection and the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Philadelphia: Philadelphia Museum of Art, 2004., 84–90 (with previous bibliography). The tabernacle wings in the Johnson Collection were in the Toscanelli collection, Pisa, until 1883. While this alone does not imply a Pisan provenance, Strehlke pointedly observed that two of the small figures of saints in the Johnson wings, Bartholomew and Lucy, appear modeled on the corresponding figures in the Pisa panels. He also drew a comparison between the Virgin in the Gardner Museum and the Grosseto Virgin and Child and dated both works in the mid- to late 1350s. ↩︎