Santa Maria del Carmine, Siena; E. and A. Silberman Galleries, New York; Hannah D. and Louis M. Rabinowitz (1887–1957), Sands Point, Long Island, N.Y., by 1945

The panels depicting Saint Andrew and Saint James, both 3 centimeters thick and of a vertical wood grain, have been cut out of their surrounding pediment, repaired with veneered capping strips—Saint Andrew, along the bottom and right edges, and Saint James, along both lateral edges and the bottom—and returned to their original placement within the pediment. A split at the upper right of the Saint Andrew panel has been repaired with a walnut insert, 17 by 1.5 centimeters long. The split had provoked a modest loss of gilding at the right edge of the saint’s halo, while another split, running the full height of the panel 2 to 3 centimeters from its left edge is visible as a notable discontinuity of surface level through the saint’s elbow and shoulder. Other than minor repairs along these splits and small losses in the saint’s beard and hair at the left side of his head, the paint is thin but very well preserved, although it is currently dulled by a discolored, opaque synthetic varnish. A nail, possibly once securing a batten, is embedded in the panel 3.5 centimeters from its right edge (viewed from the back) and 18 centimeters from its bottom edge. A walnut insert 2.5 centimeters wide repairs a split running the full height of the Saint James panel near its right edge. The gold ground of this panel has been abraded near the top of the framing arch, and small flaking losses have occurred along the cusps of the craquelure in the saint’s hair and beard. The paint surface otherwise is in excellent condition, although it, too, is currently dulled by a discolored synthetic varnish. A nail, possibly once securing a batten, is embedded in the panel 6 centimeters from its left edge (viewed from the back) and 17.5 centimeters from its bottom edge. The Prophet is painted on a panel support of a horizontal wood grain, still applied to the face of the pediment and embedded with it in a reconstructed modern frame. Its original dimensions, therefore, including its depth, are impossible to estimate with precision. A split in the panel, unrepaired, interrupts the tip of the prophet’s beard. The paint surface otherwise is extremely well preserved.

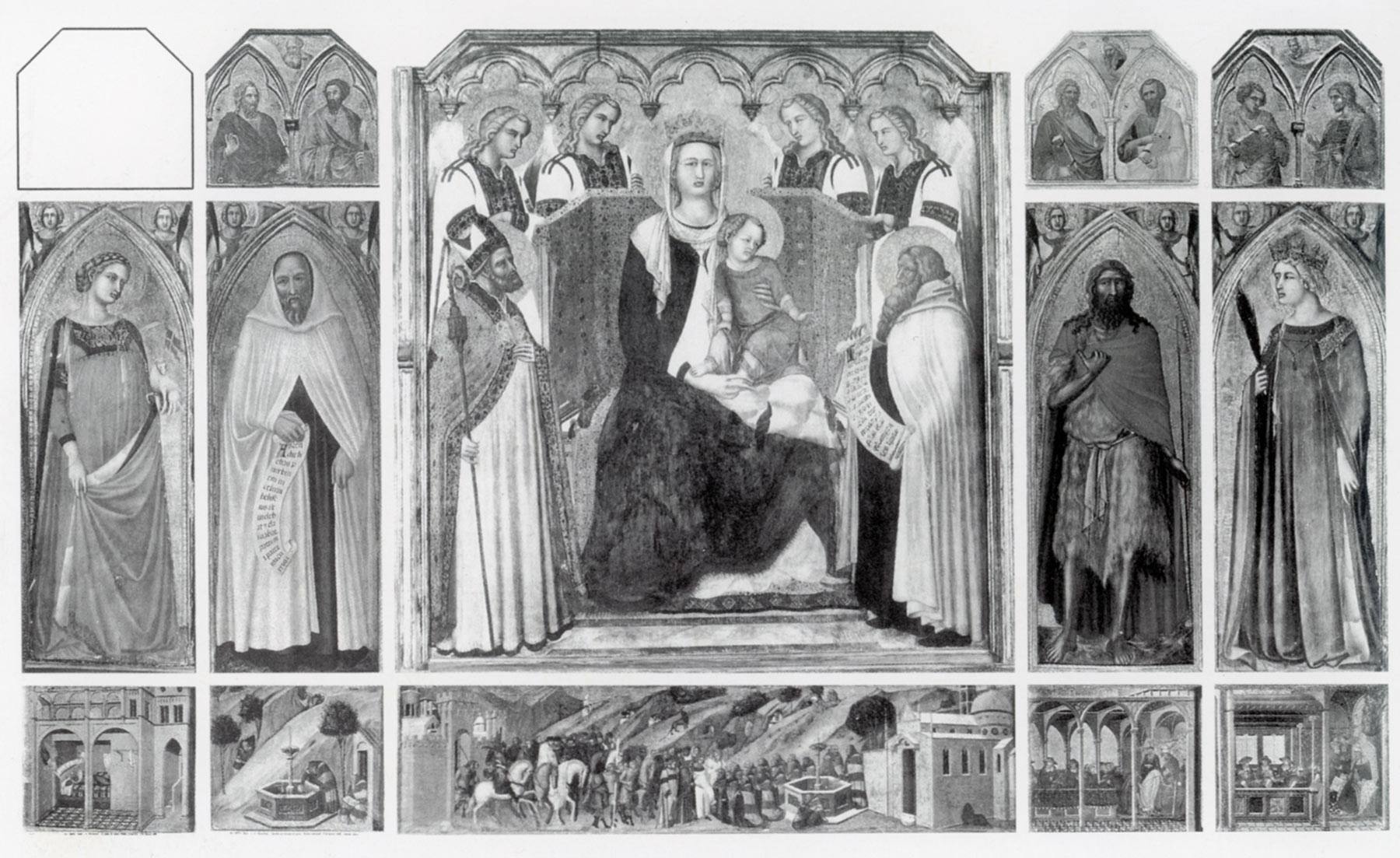

These images, enclosed in their original framing elements, were unknown to scholars until 1945, when they were published by Lionello Venturi in his catalogue of the Rabinowitz Collection.1 Venturi recognized the ensemble as one of the pinnacles of Pietro Lorenzetti’s signed and dated 1329 Carmine Altarpiece (fig. 1), an impressive multitiered polyptych executed for the monks of Santa Maria del Monte Carmelo in Siena and one of the key monuments of Sienese painting. The recovery of the Yale fragment added one more piece to the complex history and reconstruction of this important complex, already dismembered by the late sixteenth-century.

The earliest evidence for the Carmine Altarpiece is in the life of Pietro Lorenzetti compiled by the eighteenth-century Franciscan author Guglielmo della Valle, who first referred to the surviving documentary records of this commission: a resolution dated October 26, 1329, in which the Sienese commune approved the petition of the monks and prior of Santa Maria del Carmine for financial assistance so that they could “collect” the finished altarpiece from Pietro Lorenzetti’s workshop; and the subsequent disbursement of the requested sum to the artist, on November 29, 1329.2 The work, painted for the high altar of the monastery’s church, dedicated to Saint Nicholas, was described in the first document as an “admirable [honorabilem] and very beautiful panel in which the Blessed Virgin Mary and the most blessed confessor Nicholas, and apostles and Martyrs, confessors and virgins, were painted most beautifully and in great detail by Master Pietro Lorenzetti of Siena.”

In 1835 Ettore Romagnoli cited the same two documents in his own biography of Pietro Lorenzetti, adding that the altarpiece in question was “that beautiful work sold for little money in 1818 by the administrators of the Seminario [Arcivescovile]. . . . This painting, which had hung for a long time above the refectory door of that convent, was resold in Florence for a considerable sum by the person who had bought it.”3 In 1852 Gaetano Milanesi recognized that four scenes with Carmelite episodes that had been in the Pinacoteca Nazionale, Siena, since at least 1842 were most likely fragments of the altarpiece’s predella.4 The same author, who later published the above documents in their entirety, repeated Romagnoli’s information, but possibly privy to other details regarding one or more sales, he wrote that “this panel was removed from the high altar of the church of the Carmine, and was hanging above the Convent’s refectory door, when in 1818 it was sold in England.”5

Ironically, well before the purported 1818 sale, which may have applied to some of the subsidiary parts of the polyptych, the signed and dated central compartment, with the Virgin and Child, had already made its way to the small parish church of Sant’Ansano a Dofana, in the environs of Siena, where it went unrecognized by Romagnoli and all subsequent nineteenth-century scholars.6 J. B. Crowe and G. B. Cavalcaselle described the work in great detail, highlighting its very poor state of preservation, in their 1864 volume of the History of Painting in Italy: “The earliest altarpiece signed by Pietro is that of the Cappellina del Martirio in the little church of S. Ansano, belonging to the Compagnia a Dofana outside the Pispini gate of Sienna [sic], in which the Virgin, almost life size, is enthroned under the guard of four angels, between S. Anthony the abbot and S. Nicholas, erect at her sides. On the step of the throne are the words: “Petrus Laurētii de Senis me pinxit A.D. MCCCXXVIIII” (fig. 2).7 The connection between this painting and the Carmine commission was not made until the following century, when Ernst DeWald noticed the later repaints that had transformed the figure of the Prophet Elijah, the mythical founder of the Carmelite order, into a Saint Anthony Abbot. Dewald’s discovery laid the groundwork for his later identification of two other previously overlooked fragments in the Pinacoteca Nazionale, Siena: the two pinnacles with Saints Thaddeus and Bartholomew and Saints Thomas and James Minor, companions to the present figures.8

In 1939 Pèleo Bacci devoted a comprehensive study to the Carmine Altarpiece, in which he chronicled the various restorations of the Dofana panel up to his time, from the earliest intervention in 1883 to the latest in 1936.9 On that occasion, a cleaning revealed, in addition to the figure of Elijah dressed in the Carmelite habit, the original predella scene with the Carmelites Receiving the Rule, which had been painted over with scenes from the life of Saint Ansanus when the work was relocated to the oratory dedicated to that saint in the sixteenth century or later.10 In the first attempt at a reconstruction of the Carmelite polyptych, Bacci associated with the altarpiece the two full-length images of Saint Agnes and Saint Catherine of Alexandria, clearly laterals of a large complex, that had been transferred to the Pinacoteca Nazionale, Siena, in 1902 from the Sienese convent of Sant’Egidio.11 Bacci’s proposal was dismissed by subsequent scholars until the emergence on the New York art market, in 1971, of two other laterals, clearly related to the female saints, showing Saint John the Baptist and Elijah’s successor, Elisha, dressed in the Carmelite habit.12 The recovery of the four panels allowed Federico Zeri and Hayden Maginnis, followed by later authors, to obtain an almost complete picture of the original structure.13 In 1989 Volpe corrected Brandi’s original placement of the three surviving pinnacles—echoed in Piero Torriti’s 1977 reconstruction—by situating the Saints Thomas and James Minor in Siena at the extreme right of the altarpiece, above Saint Catherine of Alexandria and next to the Yale Apostles and the standing Saint John the Baptist (see fig. 1).14 Still unidentified or lost are the pair of apostles that crowned Saint Agnes on the extreme left. Based on the altarpiece type, Christa Gardner von Teuffel added to the missing elements a broad central pinnacle with its uppermost gable; the outer buttresses necessitated by the extreme width of the polyptych; and other unidentified parts of the framework.15

It has been suggested that Pietro Lorenzetti’s imposing structure remained on the high altar of San Niccolò al Carmine through the first half of the sixteenth century, until it was replaced, later in the century, with the “magnificent” wood and gilt tabernacle for the Sacrament described by Francesco Bossio in 1575.16 It is worth noting, however, that in his study of the Carmelite convent, Vittorio Luisini dated the construction of the new high altar described by Bossio to “the end of the fifteenth century,” noting that the wood tabernacle was placed on it at a later moment. One cannot discount the possibility, therefore, that Pietro’s altarpiece was dismantled before the sixteenth century and that the various components were relocated to other parts of the convent or transferred to other institutions earlier than hitherto supposed. Within such a context, it is tempting to identify the Norton Simon Elisha with that “beautiful image of Saint Benedict” by Pietro Lorenzetti, which the late fifteenth-century historian Sigismondo Tizio (1458–1528) saw hanging in the church of the Umiliati in Siena and identified as the only surviving fragment of an altarpiece painted by the artist for that church in 1329.17 The panel, located on a pillar to the right of the high altar, according to Tizio, had disappeared by Romagnoli’s time. While it is altogether possible that Pietro did execute another lost work for the Umiliati in the same years as the Carmine commission, the coincidence in date and the fact that Tizio could easily have mistaken the figure of Elisha for Saint Benedict—who is usually shown as a bearded older monk in a white habit—leave room for speculation.18

As ambitious in size as in content, Pietro’s altarpiece was conceived as a grand manifesto of the Carmelite order, providing a detailed visual account of its foundation “before it was coherently expressed in writing.”19 As acknowledged by the Sienese commune in their acceptance of the monks’ petition, the completed structure was a remarkable achievement, especially in terms of the attention devoted to the narrative predella, whose size and elaborate storytelling were unprecedented in Siena or Florence at this date.20 Almost half a meter tall, the predella scenes illustrate in chronological sequence and extraordinary detail the salient episodes of Carmelite legend and history, beginning with Sobac’s Dream, on the extreme left; followed by the Carmelites at the Fountain of Elijah; the Carmelites Receiving the Rule by Albert of Vercelli; the Approval of the Carmelite Habit by Honorius IV (in 1286); and the Reconfirmation of the Carmelite Order by John XXII (in 1326).21 The identification of the final scene, related to recent events, has allowed modern scholarship to infer that the commission for the altarpiece must be dated shortly after 1326 and to propose a chronological parameter for its execution between around 1326 or 1327 and 1329. The longer time frame, compatible with the large scale of the endeavor, has led some authors to account for perceived differences between the Virgin and Child and the lateral panels in terms of the artist’s stylistic development over this period.22 The vicissitudes suffered by the central compartment, however, make such distinctions difficult to support. Proposals to discern the intervention of assistants in other parts of the work have also been unconvincing.23 —PP

Published References

Venturi, Lionello. The Rabinowitz Collection. New York: Twin Editions, 1945., 3–4; Carli, Enzo. I capolavori dell’arte senese. Florence: Electa, 1947., 44; Brandi, Cesare. “Ricomposizione e restauro della pala del Carmine di Pietro Lorenzetti.” Bollettino d’arte, ser. 4, 33, no. 1 (January–March 1948): 68–77., 69, 72, fig. 5; An Exhibition of Paintings, for the Benefit of the Research Fund of Art and Archaeology, The Spanish Institute, Inc. New York: E. and A. Silberman Galleries, 1955., 14, no. 2; Carli, Enzo. Les siennois. Paris: Braun, 1957., 38; “Recent Gifts and Purchases: February 22–December 31, 1959.” Yale University Art Gallery Bulletin 26, no. 1 (December 1960): 52–58., 54; Seymour, Charles, Jr. The Rabinowitz Collection of European Paintings. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1961., 7, 12–13, 55; Berenson, Bernard. Italian Pictures of the Renaissance, A List of the Principal Artists and Their Works with an Index of Places: Central Italian and North Italian Schools. 3 vols. London: Phaidon, 1968., 1:219; Seymour, Charles, Jr. Early Italian Paintings in the Yale University Art Gallery. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1970., 75–77, nos. 51a–c; Fredericksen, Burton B., and Federico Zeri. Census of Pre-Nineteenth-Century Italian Paintings in North American Public Collections. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1972., 601; Zeri, Federico. “Pietro Lorenzetti: Quattro pannelli dalla pala del 1329 al Carmine.” Arte illustrata 58 (1974): 146–56., 146, 154, 156, fig. 14; Maginnis, Hayden B. J. “Pietro Lorenzetti’s Carmelite Madonna: A Reconstruction.” Pantheon 33 (1975): 10–16., 10, 15n13, fig. 14; Torriti, Piero. La Pinacoteca Nazionale di Siena. Vol. 1, I dipinti dal XII al XV secolo. Genoa: Sagep, 1977., 98; Carli, Enzo. La pittura senese del trecento. Milan: Electa, 1981., 159; van Os, Henk. Sienese Altarpieces, 1215–1460: Form, Content, Function. Vol. 1, 1215–1460. Groningen, Netherlands: Egbert Forsten, 1984., 99, fig. 114; Monica Leoncini, in Castelnuovo, Enrico, ed. La pittura in Italia: Il duecento e il trecento. 2 vols. Milan: Electa, 1986., 2:591; Cannon, Joanna. “Pietro Lorenzetti and the History of the Carmelite Order.” Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 50 (1987): 18–28., 19; Frugoni, Chiara. Pietro and Ambrogio Lorenzetti. Cinisello Balsamo, Milan: Scala, 1988., 8; Volpe, Carlo. Pietro Lorenzetti. Milan: Electa, 1989., 135, 148–49, no. 116; Kenney, Elise K., ed. Handbook of the Collections: Yale University Art Gallery. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1992., 133; De Benedictis, Cristina. “Lorenzetti, Pietro.” In Enciclopedia dell’arte medievale. Rome: Istituto della Enciclopedia Italiana, 1994.; Alessio Monciatti, in Frugoni, Chiara, ed. Pietro e Ambrogio Lorenzetti. Florence: Le Lettere, 2002., 63–64; Rowlands, Eliot W. Masaccio: Saint Andrew and the Pisa Altarpiece. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2003., 78; De Marchi, Andrea. La pala d’altare: Dal paliotto al polittico gotico. Florence: Art e Libri, 2009., 87; Gardner von Teuffel, Christa. “The Carmelite Altarpiece (circa 1290–1550): The Self-Identification of an Order.” Mitteilungen des Kunsthistorischen Institutes in Florenz 57, no. 1 (January 2015): 3–42., 16–18n76; Shaneyfelt, Sheri F. “The Marian Altarpieces of Pietro and Ambrogio Lorenzetti.” In A Companion to Late Medieval and Early Modern Siena, 113–31. Ed. Santa Casciani and Heather Richardson Hayton. Leiden, Netherlands: Brill, 2021., 118n16

Notes

-

Venturi, Lionello. The Rabinowitz Collection. New York: Twin Editions, 1945., 3–4. The history of the panels prior to their acquisition by the E. and A. Silberman Galleries, New York, is unknown. A nineteenth-century wax seal with a count’s crest on the reverse of Saint James the Greater remains unidentified. ↩︎

-

Della Valle, Guglielmo. Lettere sanesi. Vol. 2. Rome: G. Salomoni, 1785., 209–10, later transcribed by Milanesi, Gaetano. Documenti per la storia dell’arte senese. 3 vols. Siena: n.p., 1854–56., 1:193–94, no. 39; and Bacci, Pèleo. “L’elenco delle pitture, sculture e architetture di Siena, compilato nel 1625–26 da Mons. Fabio Chigi poi Alessandro VII.” Bullettino senese di storia patria 46 (1939): 297–337., 83–86, 88–89, docs. 7, 9. ↩︎

-

Romagnoli, Ettore. Biografia cronologica de’ bellartisti senesi. 12 vols. Siena: S.P.E.S., 1835. Online edition curated by Paola Barocchi, Fondazione Memofonte onlus, https://www.memofonte.it/home/files/pdf/Romagnoli_biografia_cronologica_de_bell_artisti_senesi_II.pdf., 2: fols. 359–60. ↩︎

-

Inv. nos. 83–84. Milanesi, Gaetano. Catalogo della Galleria dell’Istituto di Belle Arti di Siena. Siena: G. Landi e N. Alessandri, 1852., 14–15. ↩︎

-

Milanesi, Gaetano. Documenti per la storia dell’arte senese. 3 vols. Siena: n.p., 1854–56., 1:194. ↩︎

-

Ettore Romagnoli (in Romagnoli, Ettore. Biografia cronologica de’ bellartisti senesi. 12 vols. Siena: S.P.E.S., 1835. Online edition curated by Paola Barocchi, Fondazione Memofonte onlus, https://www.memofonte.it/home/files/pdf/Romagnoli_biografia_cronologica_de_bell_artisti_senesi_II.pdf., fol. 369) referred to the painting as a “Virgin and Child between Saints John the Baptist, Saint Peter and two bishop saints with four angels above . . . much ruined by the humidity,” and inscribed below: “Petrus Laurentii de’ Senis. 1379 [sic],” giving rise to much later confusion and speculation about two different works in the same church. It is much more likely, as noted by Pèleo Bacci (in Bacci, Pèleo. “L’elenco delle pitture, sculture e architetture di Siena, compilato nel 1625–26 da Mons. Fabio Chigi poi Alessandro VII.” Bullettino senese di storia patria 46 (1939): 297–337., 42), that the writer was working from distant memory or based on flawed hearsay. ↩︎

-

Crowe, J. A., and G. B. Cavalcaselle. A History of Painting in Italy from the Second to the Sixteenth Century, Drawn Up from Fresh Material and Recent Researches in the Archives of Italy, as Well as from Personal Inspection of the Works of Art Scattered throughout Europe. 3 vols. London: J. Murray, 1864., 2:119–20. It is curious that the authors mentioned the documents pertaining to the Carmine Altarpiece in the next passage but, presuming it had been sold in 1818, thought the artist had signed and dated two paintings in the same year. The Dofana Madonna was also examined by Francesco Brogi in 1863 (see Brogi, Francesco. Inventario generale degli oggetti d’arte della provincia di Siena (1862–1865). Siena: Nava, 1897., 86), although the author read the date as “M.CCC.XXVIII,” the last part of the inscription having been eroded and less legible due to a vertical split of the panel at this point. See note 8, below. ↩︎

-

Inv. nos. 62, 64. DeWald, Ernest. “The Carmelite Madonna of Pietro Lorenzetti.” American Journal of Archaelogy 24, no. 1 (January–March 1920): 73–76., 73–76; and DeWald, Ernest. Pietro Lorenzetti. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1930., 9–11, 18–19. Regarding the inscribed date of the altarpiece, sometimes reported as 1328, De Wald (in DeWald, Ernest. Pietro Lorenzetti. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1930., 10) pointedly noted, “Because of the condition of the panel only a tip of the last ‘I’ was visible when I saw it. This has evidently escaped those who have read the date as 1328.” ↩︎

-

Bacci, Pèleo. “L’elenco delle pitture, sculture e architetture di Siena, compilato nel 1625–26 da Mons. Fabio Chigi poi Alessandro VII.” Bullettino senese di storia patria 46 (1939): 297–337., 35–64. ↩︎

-

Pinacoteca Nazionale, Siena, inv. no. I.B.S. 16 b. The actual date of the transfer is unknown but is surmised from the dating of the oil repaints in the predella. These have been generally placed in the late sixteenth century but could be later. They were estimated to be seventeenth century by the earliest restorers; cited in Bacci, Pèleo. “L’elenco delle pitture, sculture e architetture di Siena, compilato nel 1625–26 da Mons. Fabio Chigi poi Alessandro VII.” Bullettino senese di storia patria 46 (1939): 297–337., 49. Carlo Volpe (in Volpe, Carlo. Pietro Lorenzetti. Milan: Electa, 1989., 137) thought that the painting had most likely been moved to the chapel in Dofana “after the 16th century.” ↩︎

-

Inv. nos. 578–79. ↩︎

-

Norton Simon Museum, Pasadena, Calif., inv. nos. F.1973.08.1.P, F.1973.08.2.P. Federico Zeri (in Zeri, Federico. “Pietro Lorenzetti: Quattro pannelli dalla pala del 1329 al Carmine.” Arte illustrata 58 (1974): 146–56., 148) reported that he was first shown the panels in 1971 by an unidentified dealer in New York. According to information on the Norton Simon website both works were sold in 1972 by the descendants of Jerome Bonaparte Wheat (1809–1895) to the Newhouse Galleries, New York (in partnership with Bruno Meissner, Frederick Mont and Piccolo). They were purchased by the Norton Simon Foundation from Frederick Mont in 1973; see Norton Simon Museum, “The Prophet Elisha,” https://www.nortonsimon.org/art/detail/F.1973.08.2.P. Not much is known of Jerome Bonaparte Wheat, and whether he owned other works of art. Born in Glastonbury, Connecticut, on April 12, 1809, he practiced dentistry in Charleston, South Carolina (1837), Philadelphia (1842–46), and New York. He is recorded as living in Brooklyn between 1879 and 1887, before moving back to Connecticut. He died in New Haven on June 7, 1895. The two paintings were inherited by Wheat’s daughter, Blanche Wheat Bauer (1878–1938), born from his second marriage to Helen Jeffrey, in New York. Although Wheat could have acquired the panels in the United States, the family did have connections in Europe (another of Wheat’s daughters, from his first wife, married a Polish count—a physician—in Paris) and must have traveled overseas, leaving open the possibility that they were purchased there. See Scranton, Helen Love, ed. Wheat Genealogy. Vol. 2. Guilford, Conn.: Shore Line Times, 1960., 218–19. ↩︎

-

Zeri, Federico. “Pietro Lorenzetti: Quattro pannelli dalla pala del 1329 al Carmine.” Arte illustrata 58 (1974): 146–56., 146–56; and Maginnis, Hayden B. J. “Pietro Lorenzetti’s Carmelite Madonna: A Reconstruction.” Pantheon 33 (1975): 10–16., 10–16. ↩︎

-

Volpe, Carlo. Pietro Lorenzetti. Milan: Electa, 1989., 148–49, nos. 114–16; and Torriti, Piero. La Pinacoteca Nazionale di Siena. Vol. 1, I dipinti dal XII al XV secolo. Genoa: Sagep, 1977., 99. ↩︎

-

Gardner von Teuffel, Christa. From Duccio’s Maestà to Raphael’s Transfiguration: Italian Altarpieces and Their Settings. London: Pindar, 2005., 138–39. ↩︎

-

Francesco Bossio, Visita apostolica, Siena, Archivio Arcivescovile, Sante Visite 2, fol. 687, transcribed by Lusini, Vittorio. La chiesa di S. Niccolò del Carmine in Siena. Siena: n.p., 1907., 41n1; and Israëls, Machtelt. “Sassetta’s Arte della Lana Altar-Piece and the Cult of Corpus Domini in Siena.” Burlington Magazine 143, no. 1182 (September 2001): 532–43., 534. According to Bossio, the new tabernacle was commissioned by the Arte della Lana, whose involvement with the affairs of the Carmine dated to 1431, when they took over the patronage of the main chapel. Machtelt Israëls has postulated that the Arte della Lana’s involvement in the upkeep of the high altar might account for the transformation of the figure of Elijah into Saint Anthony Abbot, one of the guild’s first patron saints. While this is an interesting suggestion, it seems unlikely that the Carmelite friars would have allowed for the replacement of the founder of their order in the main panel of an altarpiece dedicated to the history of its foundation. Most monastic orders were reluctant to concede any ius patronatus over the high altar, notwithstanding the involvement of a lay entity or benefactor, and Bossio’s description stated specifically that the altar was not endowed (“non dotatum”) at the time of his writing. See Gardner von Teuffel, Christa. From Duccio’s Maestà to Raphael’s Transfiguration: Italian Altarpieces and Their Settings. London: Pindar, 2005., 372–98, 656–66. ↩︎

-

Sigismundi Titii, Historiae senenses 2, fols. 485–86, Biblioteca Comunale, Siena, MS B.III, 7; cited by Della Valle, Guglielmo. Lettere sanesi. Vol. 2. Rome: G. Salomoni, 1785., 208 and transcribed by Bacci, Pèleo. “L’elenco delle pitture, sculture e architetture di Siena, compilato nel 1625–26 da Mons. Fabio Chigi poi Alessandro VII.” Bullettino senese di storia patria 46 (1939): 297–337., 81–82, doc. 5. ↩︎

-

Carlo Volpe, in Volpe, Carlo. Pietro Lorenzetti. Milan: Electa, 1989., 134, thought that Tizio’s reference might apply to the predella fragments with Saint Anthony Abbot and the Man of Sorrows, presently divided between the Alana Collection, Newark, Del., inv. no. 2012.43, and the Museo Civico Amedeo Lia, La Spezia, inv. no. 133. ↩︎

-

Gardner von Teuffel, Christa. “The Carmelite Altarpiece (circa 1290–1550): The Self-Identification of an Order.” Mitteilungen des Kunsthistorischen Institutes in Florenz 57, no. 1 (January 2015): 3–42., 38. Christa Gardner von Teuffel’s exhaustive discussion of the visual program of Pietro’s altarpiece follows upon the foundational study by Joanna Cannon; see Cannon, Joanna. “Pietro Lorenzetti and the History of the Carmelite Order.” Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 50 (1987): 18–28., 18–28. See also van Os, Henk. Sienese Altarpieces, 1215–1460: Form, Content, Function. Vol. 1, 1215–1460. Groningen, Netherlands: Egbert Forsten, 1984., 91–103; Frugoni, Chiara. Pietro and Ambrogio Lorenzetti. Cinisello Balsamo, Milan: Scala, 1988., 8–13; and Alessio Monciatti, in Frugoni, Chiara, ed. Pietro e Ambrogio Lorenzetti. Florence: Le Lettere, 2002., 63–64. It bears restating that Cannon (in Cannon, Joanna. “Pietro Lorenzetti and the History of the Carmelite Order.” Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 50 (1987): 18–28., 23n48) convincingly pointed out that the inclusion of Saints Agnes and Catherine in the altarpiece could not be related to the Arte della Lana, as first suggested by Zeri (in Zeri, Federico. “Pietro Lorenzetti: Quattro pannelli dalla pala del 1329 al Carmine.” Arte illustrata 58 (1974): 146–56.) and repeated in the following literature since the guild became involved with the Carmine only in the fifteenth century (see note 16, above). On the other hand, as Cannon pointedly observed, Saint Agnes was, together with the Virgin, joint patron saint of the confraternity attached to the church of the Carmine in Florence, suggesting that there existed an affiliation between her and the order. ↩︎

-

De Marchi, Andrea. La pala d’altare: Dal paliotto al polittico gotico. Florence: Art e Libri, 2009., 87. ↩︎

-

The original sequence of the last two scenes, whose order had been inverted in earlier reconstructions, was reestablished following the 1997–98 restorations; see Gardner von Teuffel, Christa. “The Carmelite Altarpiece (circa 1290–1550): The Self-Identification of an Order.” Mitteilungen des Kunsthistorischen Institutes in Florenz 57, no. 1 (January 2015): 3–42., 23. ↩︎

-

Alessio Monciatti, in Frugoni, Chiara, ed. Pietro e Ambrogio Lorenzetti. Florence: Le Lettere, 2002., 68. ↩︎

-

Seymour, Charles, Jr. Early Italian Paintings in the Yale University Art Gallery. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1970., 75–77, nos. 51a–c. ↩︎