Edward Hutton (1875–1969), London; Maitland Fuller Griggs (1872–1943), New York1

The panel, of a vertical wood grain, retains its original thickness of 2.9 centimeters and exhibits a modest convex warp. Modern frame moldings have been engaged along its top and sides and three horizontal braces have been secured across its reverse, which is heavily impregnated with wax. Indications of two batten channels, approximately 8 centimeters wide, cross the panel at 10 centimeters (on center) from the top of the panel and 12 centimeters from the bottom. The present spandrel moldings and decoration are modern, as is the tabernacle-style base of the frame. The barb of gilding and paint where this base molding meets the picture surface may or may not be original, but a drawn line beneath the paint demarcating the end of the composition implies that its format has not been altered. The picture surface has been lightly and evenly abraded from vigorous cleaning, but it and the gold ground are overall beautifully preserved. Scratches through the book and hands of Saint John have been discreetly inpainted, as have minor flaking losses in the saint’s draperies caused by a split in the panel rising from the bottom edge slightly left of center. A similar split at the top edge of the panel along its center has resulted in no appreciable loss of gilding. The engraved outlines of an inkwell set against the gold ground at the lower-left corner of the composition may have been covered by now-lost pigment or glazes, but none are in evidence: this may be the remnants of a design idea not ultimately realized by the artist.

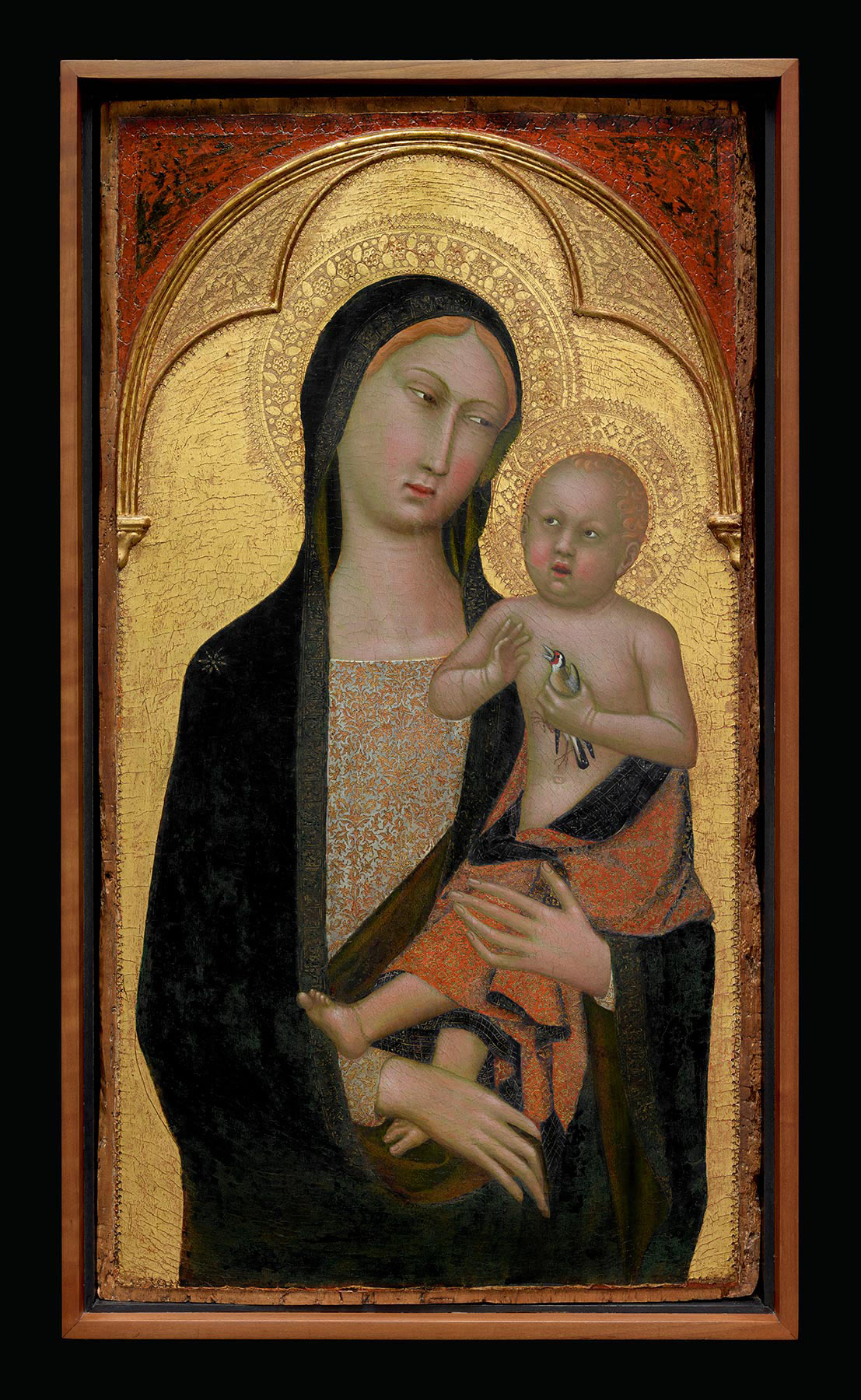

A relatively recent addition to the body of works involved in the contentious debates around the identities of Simone Martini’s closest followers, the Griggs Saint John the Evangelist was, ironically, first recorded only after Maitland Griggs’s death, when Richard Offner mentioned it as a possible companion to a panel in the Percy Straus Collection (fig. 1), then recently donated to the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston.2 Shortly afterward, John Pope-Hennessy confirmed and elaborated this suggestion, arguing on the basis of the unusual shape of their picture fields and the consonance of their dimensions (Pope-Hennessy had, however, been supplied with incorrect dimensions for the Griggs panel that included its modern frame) that these two panels were certainly fragments of a single altarpiece.3 He attributed both of them to the assistant of Barna da Siena responsible for the less-accomplished frescoes among the New Testament scenes in the Collegiata at San Gimignano, works that were later to be reassigned in their entirety to Lippo Memmi and his workshop. The Houston panel had previously been discussed as the eponymous work of an artist isolated by Curt Weigelt and named by him the “Master of the Straus Madonna” (sometimes designated in later literature as the “Master of the Sienese Straus Madonna” to distinguish him from an early fifteenth-century Florentine artist assigned the same name).4 While Pope-Hennessy accepted the integrity of Weigelt’s grouping and its stylistic proximity to Barna da Siena, he rejected his contention that a half-length image of Saint Agnes in the Worcester Art Museum, Massachusetts (fig. 2), might have been a lateral panel from the same altarpiece as the Straus painting—and by extension a companion to the Griggs Evangelist as well—a proposal that had been accepted by Offner but that has been rejected by nearly all later writers except Carolyn Wilson.5

Setting aside the bewildering range of proposals by later writers for additions to or subtractions from the group isolated by Weigelt as by the Master of the Sienese Straus Madonna or the shuffling of members of this group within the canon of other Simonesque painters variously identified as Barna, the Pseudo-Barna, the Master of the Palazzo Venezia Madonna, Donato Martini, Tederigo Memmi, or Lippo Memmi, the one constant running through all the bibliography related to the Griggs painting has been the assumption that it and the Straus Madonna in Houston are fragments of the same altarpiece. In a paper delivered at a College Art Association (CAA) conference in February 2006, however, conservators at the Worcester Art Museum demonstrated that this cannot have been the case.6 Not only are the panels radically different in size, but also the embedded nails intended to secure battens across their backs do not align. The Houston panel, furthermore, retains dowel holes along its left and right sides that originally held it in plane with its adjacent lateral panels, whereas the Griggs panel shows (in an X-radiograph; the engaged modern frame prevents direct visual inspection) no evidence of dowel cavities. Finally, the gold ground in the Houston panel is decorated with punch tooling lining its arches, vertical margins, and bottom edge, while no tooling appears along the bottom edge of the Griggs panel. In the same CAA paper, it was definitively concluded that the Worcester Saint Agnes originated from yet a third complex, distinct from either the Houston or Griggs panels. The style of each of these works, therefore, needs to be considered independently of the others rather than as an indivisible unit, as it has been approached throughout the existing literature.

Even though it can be assumed that the Griggs and Houston panels are not fragments of a single altarpiece, it must be acknowledged that they were painted by the same artist and probably at no great distance of time from each other. Each can independently be associated on stylistic grounds with the beautifully preserved diptych of the Annunciation (fig. 3) and the Lamentation over the Dead Christ (fig. 4) that is a central feature of nearly all discussions of the Barna/Straus Master group of paintings; indeed, for Millard Meiss, Federico Zeri, and Carlo Volpe, this diptych was the defining member of the group and deserved to be the name-piece of an eponymous master.7 Volpe, in particular, stressed the relationship of the considerably damaged Madonna in Houston to the diptych and emphasized the distinctions between these three paintings and nearly everything else that had been grouped with them by Weigelt. He argued in favor of dismantling the so-called Master of the Sienese Straus Madonna and for recognizing the other paintings isolated by Weigelt as variously assignable either to Barna (alias Master of the Ashmolean Lamentation) or to the Master of the Palazzo Venezia Madonna, an independent follower of Simone Martini and Lippo Memmi. The latter remains a vague and elusive personality but can in general be described as more closely dependent on models by Simone and Lippo; as more linear in his modeling and less responsive to opportunities for creating pictorial space; and as more exaggerated or theatrical in the emotional tenor of his figures, without the emotive sincerity of the artist known as Barna.

Volpe’s critique of Weigelt’s proposals rests on solid visual arguments and must be accepted as valid. Although he did not specifically address the case of the Griggs Evangelist (except by implication through its association with the Houston panel), it may be assumed that he considered it, too, to be a member of the Barna group. At the same time, “Barna” must now be understood to be a name of convenience designating a group of works that almost certainly were painted by Lippo Memmi (see Lippo Memmi, Saint John the Evangelist, inv. no. 1943.239). The “Barna” group does not represent a distinctive stage within Lippo’s career but reveals instead a long tradition of critical misunderstanding of Lippo Memmi as an artist. It is likely, though not susceptible of proof, that the subgroup of paintings related to the Annunciation/Lamentation diptych, the Straus Madonna, and the Griggs Evangelist are to be situated at the end of Lippo Memmi’s long and productive career, close in time to the fragmentary fresco of the Virgin and Child with Saints Peter, Paul, and Dominic removed from a wall in the cloister of San Domenico in Siena and now displayed in the Pinacoteca Nazionale there—a fresco that was said by Fabio Chigi in his manuscript of 1625 to have been signed by Lippo Memmi and dated 1350.8 The paintings of the so-called Master of the Palazzo Venezia Madonna—among which is probably to be numbered the Worcester Saint Agnes (see fig. 2)—are also strongly dependent on works from this period in Lippo’s career, accounting, in some measure, for the persistent confusion between some of them and works in the Barna group.

A model for the altarpiece of which the Griggs Evangelist once formed part is likely to be provided by the polyptych from Casciana Alta, now displayed in the Museo Nazionale di San Matteo in Pisa and widely attributed to Lippo Memmi and his workshop in Pisa.9 The proportions and shape of the lateral panels in this altarpiece, including the delineation of their picture fields by a rounded rather than ogival trilobe arch, closely approximate those of the Griggs panel. The Casciana Alta polyptych is preserved intact with its triangular gables, and the relation in size between these and the lateral panels below them suggest the possibility that a triangular gable showing a bishop saint in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (fig. 5), may well have been excised from the Griggs Evangelist or from another panel in the same altarpiece, as has been suggested by the present author.10 It must, however, be acknowledged that the association between these paintings is based primarily on the repetition of punch motifs within them and on a general similarity of style and technique, evidence that would permit a reconstruction but that cannot demonstrate one. In practice, the Boston pinnacle could have stood above almost any painting by Lippo Memmi from this period in his career, and there can be no certainty even that its original subjacent panel survives. Lacking further physical evidence, the proposal for a reconstruction must be regarded as speculative. —LK

Published References

Offner, Richard. “The Straus Collection Goes to Texas.” Art News 44, no. 7 (May 15–31, 1945): 16–23., 17; Pope-Hennessy, John. “Barna, the Pseudo-Barna and Giovanni d’Asciano.” Burlington Magazine 88, no. 515 (February 1946): 34–37., 35–37; Berenson, Bernard. Italian Pictures of the Renaissance, A List of the Principal Artists and Their Works with an Index of Places: Central Italian and North Italian Schools. 3 vols. London: Phaidon, 1968., 1:405; Seymour, Charles, Jr. Early Italian Paintings in the Yale University Art Gallery. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1970., 69–71, no. 47; Fredericksen, Burton B., and Federico Zeri. Census of Pre-Nineteenth-Century Italian Paintings in North American Public Collections. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1972., 601; Martin Davies, in European Paintings in the Collection of the Worcester Art Museum. Worcester, Mass.: Worcester Art Museum, 1974., 456, 457n5; De Benedictis, Cristina. “Il polittico della Passione di Simone Martini e una proposta per Donato.” Antichità viva 15, no. 6 (1976): 3–11., 4, 8, 10, 11n37, fig. 12; De Benedictis, Cristina. La pittura senese, 1330–1370. Florence: Salimbeni, 1979., 91, fig. 77; Monica Leoncini, in Castelnuovo, Enrico, ed. La pittura in Italia: Il duecento e il trecento. 2 vols. Milan: Electa, 1986., 2:608; Boskovits, Miklós. Frühe italienische Malerei: Gemäldegalerie Berlin, Katalog der Gemälde. Berlin: Mann, 1988., 80, 83, 114; Kanter, Laurence. Italian Paintings in the Museum of Fine Arts Boston. Volume 1, 13th–15th Century. Boston: Museum of Fine Arts, 1994., 95–97; Wilson, Carolyn C. Italian Paintings, XIV–XVI Centuries, in the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. Houston: Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, 1996., 29, 32; Leone de Castris, Pierluigi. Simone Martini. Milan: Federico Motta, 2003., 340n60

Notes

-

There is no record of the date at which Griggs purchased this painting from Hutton nor of when or where Hutton acquired it. It is referred to in Offner, Richard. “The Straus Collection Goes to Texas.” Art News 44, no. 7 (May 15–31, 1945): 16–23., 17, as private collection, England. Three photographs of the painting in Richard Offner’s archive, now at the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., are stamped “Dino Zani & C, Corso Garibaldi 2, Milano”; “Henry Dixon & Sons, Ltd., 112 Albany St., N.W.”; and “William Edward Gray, 92 Queens Road, Bayswater.” William Edward Gray died in 1935. Henry Dixon (1820–1893) operated his studio in partnership with his son, Thomas James Dixon (1857–1943), and the studio is believed to have remained active into the early 1940s. Dino Zani (1891–1957) was a partner in the Milanese photography studio Crimella-Castagneri-Zani, founded in 1920 at corso Garibaldi, 2. There is no record of whether Zani stamping as an independent photographer implies a specific time period, but it may at least be inferred that the painting was in an Italian private collection before the Second World War. ↩︎

-

Offner, Richard. “The Straus Collection Goes to Texas.” Art News 44, no. 7 (May 15–31, 1945): 16–23., 17, no. 7. ↩︎

-

Pope-Hennessy, John. “Barna, the Pseudo-Barna and Giovanni d’Asciano.” Burlington Magazine 88, no. 515 (February 1946): 34–37., 35–37. ↩︎

-

Weigelt, Curt. “Minor Simonesque Masters.” Apollo 14 (July 1931): 1–13., 11–12. ↩︎

-

Wilson, Carolyn C. Italian Paintings, XIV–XVI Centuries, in the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. Houston: Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, 1996., 29, 32. ↩︎

-

Albertson, Rita, Morwenna Blewett, and Philip Klausmeyer. “A Technical Approach to the Master of the Sienese Straus Madonna.” Paper presented at the session “Italian Paintings in the Boston Area,” College Art Association Annual Conference, Boston, February 21, 2006.. ↩︎

-

Meiss, Millard. “Nuovi dipinti e vecchi problemi.” Rivista d’arte 30 (1955): 107–45., 142–45; Zeri, Federico. “La riapertura della Alte Pinakothek di Monaco.” Paragone 95 (November 1957): 64–68., 66; and Volpe, Carlo. “Precisazioni sul ‘Barna’ e sul ‘Maestro di Palazzo Venezia.’” Arte antica e moderna 10 (April–June 1960): 149–58., 149–58. ↩︎

-

See Cristina de Benedictis, in Mostra di opera d’arte restaurate nelle province di Siena e Grosseto. Vol. 1. Exh. cat. Genoa: Sagep, 1979., 42–44, no. 12; and Daniella Bruschettini, in Bagnoli, Alessandro, and Luciano Bellosi, eds. Simone Martini e “chompagni.” Exh. cat. Siena: Centro Di, 1985., 103–6, nos. 16–19. ↩︎

-

Caleca, Antonino. “Tre polittici di Lippo Memmi: Un’ipotesi sul Barna e la bottega di Simone e Lippo, I.” Critica d’arte 41 (1976): 49–59., 49–59; and Luciano Bellosi, in Bagnoli, Alessandro, and Luciano Bellosi, eds. Simone Martini e “chompagni.” Exh. cat. Siena: Centro Di, 1985., 94–101, no. 15. ↩︎

-

Kanter, Laurence. Italian Paintings in the Museum of Fine Arts Boston. Volume 1, 13th–15th Century. Boston: Museum of Fine Arts, 1994., 95–97. ↩︎