San Francesco, San Gimignano, to 1553; possibly San Giovanni Battista, San Gimignano, to 1782; possibly San Francesco, Colle Val d’Elsa, to before 1865; Commendatore Giulio Sterbini (died 1911), Rome, by 1905; Godefroy Brauer (1857–1923), Paris; from whom purchased by Bernard Berenson (1865–1959), Settignano, June 28, 1910; Edward Hutton (1875–1969), London; Wildenstein and Co., New York and Paris; Mrs. Benjamin Thaw (née Elma Ellsworth Dows, 1861–1931), New York, by 1917; sale, Galerie Georges Petit, Paris, May 15, 1922; Duveen Brothers, New York, 1922–24/25; Maitland Fuller Griggs (1872–1943), New York, 1925

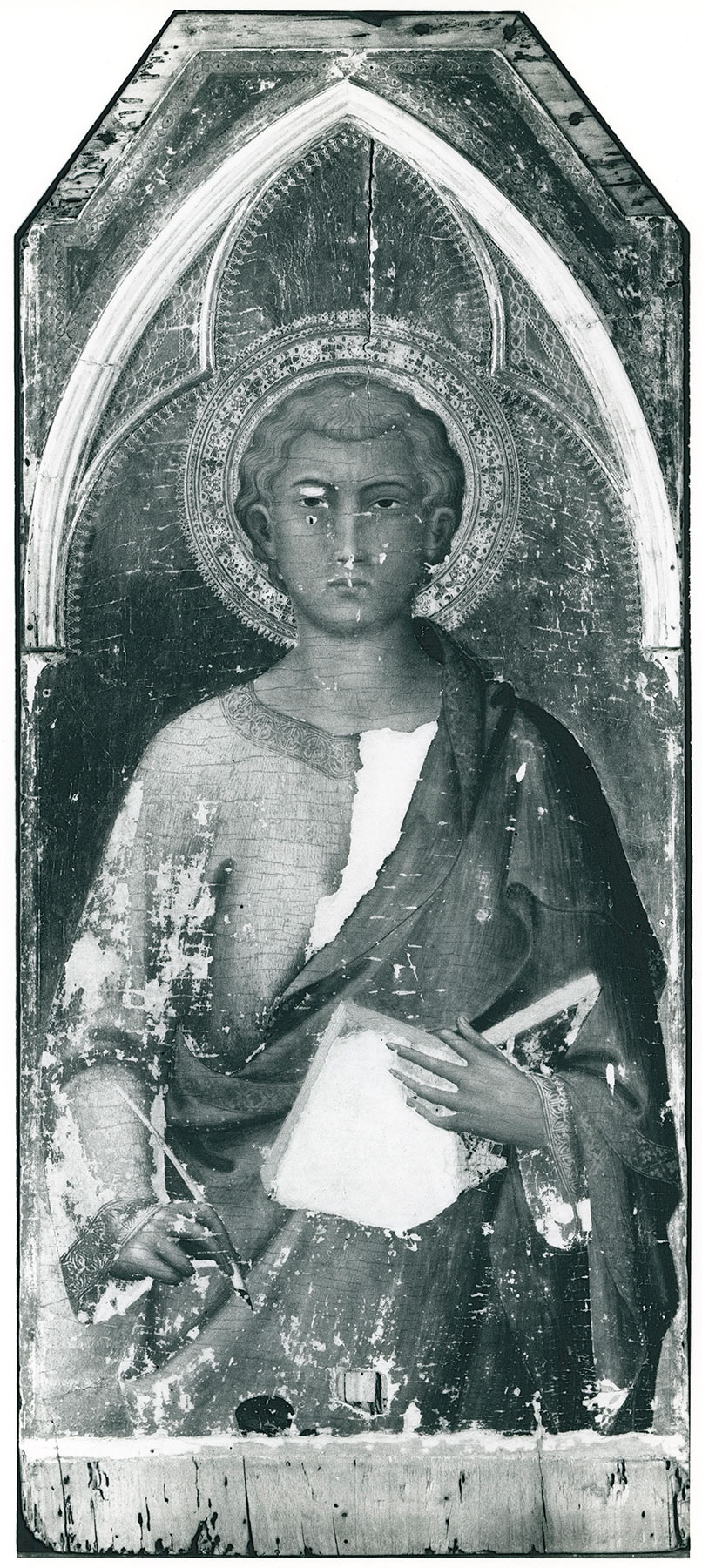

The panel, of a vertical wood grain, is 2.5 centimeters thick but may have been thinned slightly, no more than 5 millimeters, judging by the off-center positioning of the dowel holes on its edges. These occur at 7, 40.5, and 75.5 centimeters from the bottom on the left margin and at 7, 41.5, and 76.5 centimeters from the bottom on the right margin. The spandrel applied above the arch of the panel is a 7-millimeter-thick panel with a horizontal grain; its original silver decoration is missing, but the bolus, punched ornament, and blue sgraffito decoration are intact. A capping molding at the top of this spandrel is missing. A split in the primary panel support, originating at its top edge (beneath the spandrel) and extending just right of center to the level of the saint’s forehead, is open and has caused minor losses in the gold ground through which it passes. Three smaller splits rise from the bottom of the panel, only one of which, near the left edge, reaches above the 6.5-centimeter-wide area of exposed wood that originally bore an attached predella or base molding. A 1.5-centimeter-wide strip of exposed gesso and linen above this base molding probably indicates a lost portion of paint surface: no barb is visible anywhere along the bottom edge of the paint surface. A cradle formerly attached to the back of the panel was removed in 1959, and scars from batten nails 11.5 centimeters and 72.4 centimeters from the bottom were filled with wood putty.

The gilding overall is well preserved, except for approximately 1-centimeter-wide strips running the full height of each side of the panel, beneath the spring of the arch molding; presumably, applied colonettes once covered this area, which therefore may originally not have been finished with more than polished bolus. Missing corbels or capitals at the spring of the arch at each side are indicated by exposed areas of gesso. Abrasion to the gilding is greater on the right side of the panel than on the left and is particularly evident above and below the points of the trilobe framing arch, whereas the saint’s halo, the interior spandrels, and the top lobe of the arch are beautifully preserved, as is most of the gilding on the left side of the panel. The mordant gilt decoration of the saint’s robe is largely intact. The paint surface is thin but generally well preserved, with light overall abrasion. Areas of total loss, as revealed by the aggressive cleaning by Andrew Petryn in 1959 (fig. 1), affect the green cover of the saint’s book; shadowed areas in his blue tunic at the breast, right sleeve, and left cuff; and scattered smaller losses in the lower portion of his red cloak. These were filled and inpainted by Gabrielle Kopelman in 1985.

From its earliest mention in the Sterbini collection in Rome,1 the Griggs Saint John the Evangelist was consistently referred to as a work by Simone Martini2 and discussed as unrelated to any other known altarpieces or altarpiece fragments by Simone. Raimond van Marle described it as possibly a very early work by Simone, painted before he had developed his recognizable, mature style, but he acknowledged that, as it is not possible to document such a period in Simone’s career, the painting might also be the work of a close follower.3 Helen Comstock first noted that it must have formed part of the same altarpiece as panels representing Saint Paul in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (fig. 2); Saint Peter in the Musée du Louvre, Paris (fig. 3); Saint John the Baptist in the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. (fig. 4); and Saints Louis of Toulouse and Francis in the Pinacoteca Nazionale, Siena (fig. 5–6).4 Several of these, chiefly the New York and Paris panels, had previously been attributed to Lippo Memmi, and Comstock presumed, therefore, that the altarpiece was a collaborative effort between Simone and his brother-in-law, Lippo. Acknowledgment of Comstock’s reconstruction came from Federico Zeri, who rejected outright the possibility of considering the Griggs panel as a work by Simone, attributing it and the Saints Peter, Paul, and John the Baptist unequivocally to Lippo Memmi.5 This contention has not been seriously challenged other than by Charles Seymour, Jr., who wondered if the superior quality of the Griggs panel might not indicate the authorship of the supposed “Barna da Siena.”6 Seymour might, in this respect, have been mirroring Bernard Berenson’s brief flirtation with assigning the New York Saint Paul to “Barna,” a suggestion that Berenson subsequently withdrew.7 Later scholarly literature has not revived this proposal, other than an oblique reference by Alessandro Bagnoli, where the altarpiece is assigned to Lippo Memmi and his brother Federico, an encoded reference to its affiliation with the supposed “Barna da Siena.”8

While the New York Saint Paul and the Paris Saint Peter have long been recognized both as companions from a single altarpiece and as works probably by Lippo Memmi, opinions regarding the other panels associated with them by Comstock have not been unanimous. The Washington Saint John the Baptist, which was first exhibited publicly in 1934, was, like the Saint John the Evangelist, initially attributed by van Marle to Simone Martini. Klara Steinweg argued that the Saint John the Baptist and the Saint John the Evangelist may have come from a different altarpiece than the Saint Peter and Saint Paul, while Cristina De Benedictis accepted Zeri’s view that these four panels were related to one another.9 Zeri had not commented on the Saint Louis of Toulouse and Saint Francis in Siena, and De Benedictis excluded them from her reconstruction, notwithstanding the identity of their framing elements with those preserved on the Griggs Saint John the Evangelist. Removing the Franciscan saints enabled De Benedictis to accept earlier proposals for identifying the reconstructed altarpiece with one described by Giorgio Vasari in the Vallombrosan church of San Paolo a Ripa d’Arno in Pisa, said by him to have included figures of Saints Peter, Paul, and John the Baptist and to have borne Lippo Memmi’s signature.10 Gertrude Coor had previously supported this identification—even though she had included the two Franciscan saints in her reconstruction—suggesting, additionally, that three smaller panels showing the Blessing Redeemer (in Douai, France) and two Vallombrosan saints (in Altenburg, Germany) might have been pinnacles from this structure.11 Michael Mallory recognized these pinnacles as being insufficiently close in style to the other panels and incompatible in iconography with a Franciscan altarpiece.12 He related them instead to a series of four panels showing full-length figures of Saints Peter and Paul (in Palermo), John the Baptist (in Altenburg), and Andrew (in Pisa)13 and, consequently, suggested that the latter are more likely to have been part of the Pisan altarpiece seen by Vasari.

Returning to the altarpiece of which the Griggs Evangelist once formed part, Mallory further observed that the Saint Francis and Saint Louis of Toulouse in Siena were recorded in 1865 in the church of San Francesco in Colle Val d’Elsa. Since these panels conform in style, internal measurements, and frame design to the panels in New Haven, New York, Paris, and Washington, that provenance was then extended to the entire altarpiece. Establishing a Franciscan provenance for this altarpiece also allowed Mallory to propose the identification of five pinnacle panels from the structure. These included three more Franciscan saints: Saint Clare (fig. 7), in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; Saint Elizabeth of Hungary (fig. 8), in the Museo Poldi Pezzoli, Milan; Saint Anthony of Padua, in the Frick Art and Historical Center, Pittsburgh; along with Saint Agnes, also in the Frick collection, Pittsburgh (fig. 9); and Saint Mary Magdalen (fig. 10), in the Rhode Island School of Design Museum, Providence. A sixth pinnacle has been added to these more recently: Saint Augustine (fig. 11) in the Salini Collection at the Castello di Gallico, near Asciano. Finally, Bagnoli, who correctly accepted this complete reconstruction, observed that none of these panels, including the two now in Siena (where they were brought in 1867), is recorded in San Francesco at Colle Val d’Elsa in any source earlier than 1865.14 He noted instead that several fifteenth-century panels also appearing in the 1865 inventory of San Francesco at Colle Val d’Elsa are documented as commissions from the Franciscans at San Gimignano. That community relocated to Colle in 1787, following the suppression of their own convent five years earlier. This fact, combined with the prominence of the Memmi family workshop in San Gimignano, led Bagnoli to propose the church of San Francesco, outside the walls of that town, as the probable original site of this altarpiece. The church of San Francesco at San Gimignano was destroyed in 1553, at which time the friars were reassigned to conventual premises at San Giovanni Battista inside the walls of the town. They remained there until the suppression of the chapter in 1782 and their relocation to Colle Val d’Elsa in 1787.

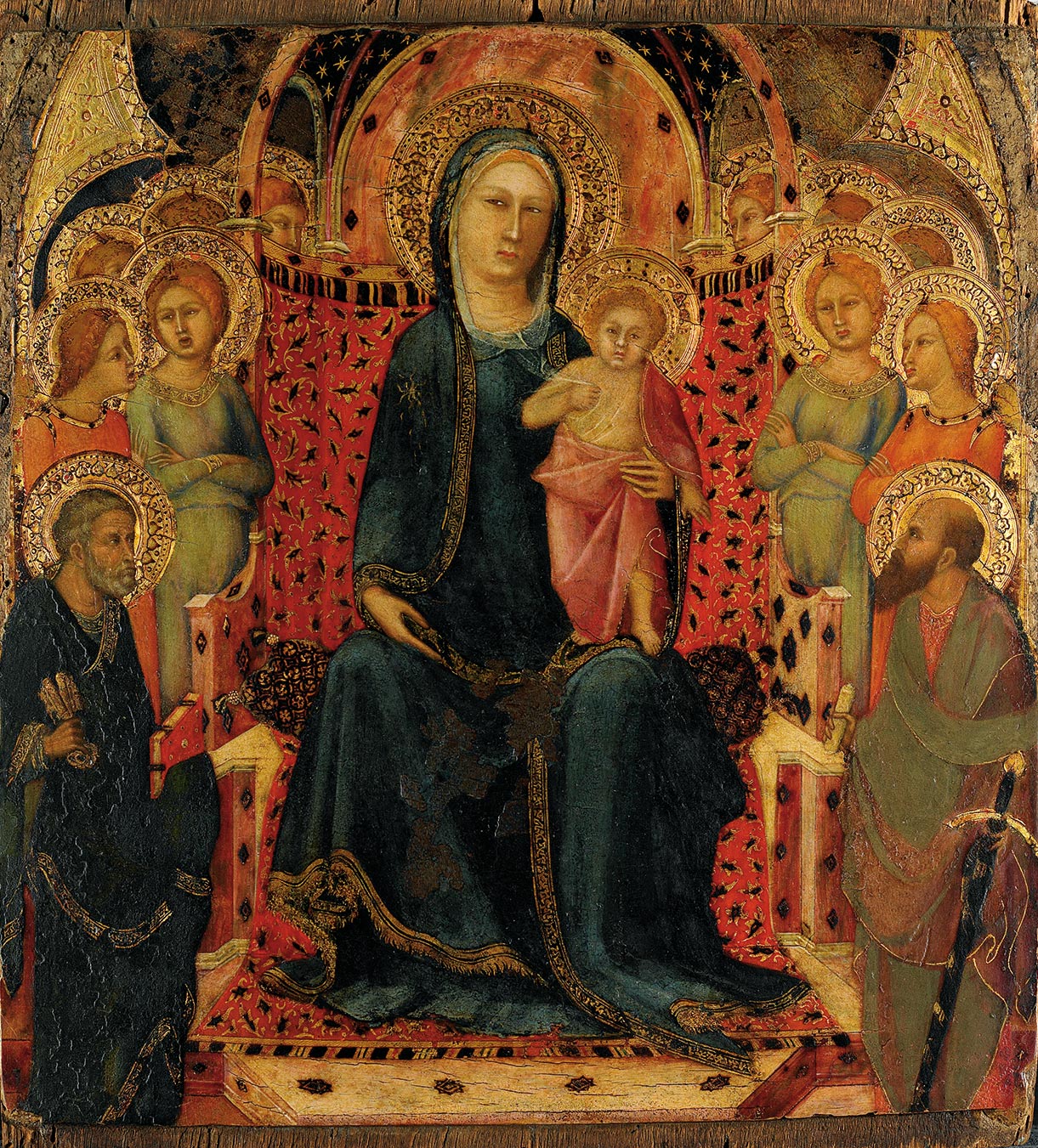

A lingering point of contention in the reconstruction of this altarpiece involves the identification of its central panel, presumably representing the Virgin and Child. Discussing the panels now in New York, Paris, and Washington, Evelyn Sandberg-Vavalà noted their similarity to a half-length Virgin and Child in the German state collections at Berlin (fig. 12) and suggested these might all have originated in a single altarpiece.15 Van Marle had already noted the relationship among the Berlin, New York, and Paris panels, without explicitly proposing a common origin;16 De Benedictis published the Berlin panel as certainly the center of this altarpiece.17 Mallory further elaborated on this reconstruction, providing supporting evidence through the correspondence of internal measurements (the Berlin panel has been truncated at the top, so its full height remains hypothetical).18 Hayden B. J. Maginnis cast doubt on the inclusion of the Berlin painting with the other six panels, noting differences in the punched decoration of their gold grounds.19 Miklós Boskovits initially, followed by Bagnoli, accepted these doubts, observing that the silver-leaf spandrel decoration in the Berlin panel does not correspond to the gilt spandrels in any of the other panels.20 Boskovits subsequently retracted his objections, however, noting that “further reflection . . . has now strengthened my suspicion that the painting in [Berlin], whose stylistic and chronological closeness to the other components of the San Gimignano polyptych is generally recognized, could possibly have formed part of it.”21

The Berlin Virgin is unlikely to have formed part of this altarpiece: the initial objections to such a reconstruction voiced by Maginnis, Boskovits, and Bagnoli were sound. The punched decoration of the Berlin Virgin and the six lateral panels implies two different and incompatible systems of framing. Punch tooling along the margins in the lateral panels follows the contours of their trilobe, ogival arches only, ending at the corbels or capitals supporting the spring of the arches on either side, indicating that the panels were divided from one another only by freestanding colonettes. The marginal decoration in the Berlin panel instead continues the full length of its sides to the bottom of the picture field, suggesting that it was separated from the panels alongside it by an engaged molding. This dichotomy is not known in any other trecento Sienese altarpiece. While it cannot be assumed that the central panel of the San Gimignano polyptych must survive, the remarkable preservation of all twelve of its lateral members argues that it might. A more promising candidate, on stylistic grounds, than the Berlin Virgin and Child is the Virgin discovered in 1957 in the parish church of San Giovanni Battista at Lucignano d’Arbia, now exhibited at the Pinacoteca Nazionale in Siena as the work of Simone Martini (fig. 13), an attribution universally accepted in the various monographs dedicated to that artist since its discovery. Although truncated at the top and entirely missing its gold ground and punched decoration, the outlines of the original frame moldings once attached to it are still clearly visible and correspond to those in the New Haven, New York, Paris, Siena, and Washington panels. The Lucignano d’Arbia Virgin is of the correct proportional scale to have formed part of this altarpiece: the height of the panel from its base to the spring of its arches (61 centimeters) is identical to that of the Griggs Saint John the Evangelist. Traces of battens remaining on the reverse of the Lucignano Virgin, however, do not align with those on the reverse of the Griggs Saint John the Evangelist, making this reconstruction also unlikely.22

The possibility of restoring a Virgin and Child attributed to Simone Martini to the San Gimignano altarpiece focuses renewed attention on the vacillating attributions historically assigned to the various panels of the complex. Distinguishing between the work of Simone Martini and Lippo Memmi has always been one of the most contentious issues in the study of fourteenth-century Italian painting. In part, this springs from the fact that, in 1333, both artists signed the altarpiece of the Annunciation from Siena Cathedral23 as collaborators and that Vasari, in his Life of Simone and Lippo, implied that they worked together frequently.24 The lack of consensus over the responsibilities of either painter within the Annunciation altarpiece has compounded a misunderstanding of Lippo Memmi’s independent personality that sprang in the first instance from Vasari’s characterization of Lippo as a derivative artist.25 Most modern scholarship has accepted as fact Vasari’s critical appraisal of Lippo Memmi: “Sebbene non fu eccellente come Simone, seguitò nondimeno quanto potè il più la sua maniera” (Although he was not as gifted as Simone, he nevertheless followed his style as best he could).26 Accordingly, Lippo has been treated as little more than a one-dimensional foil for his more famous brother-in-law, and as recently as 1960, his paintings could be described as “d’ispirazione delicata ma monotona, spesso stanca” (of delicate but monotonous, often tired, inspiration).27 This contention, however, is belied by recent arguments that one of the protagonists of early Sienese painting, the so-called Barna da Siena, who has correctly been praised as “poco al di sotto di Simone e dei Lorenzetti” (scarcely less than Simone or the Lorenzetti), is actually not an independent personality but a phase in the career of Lippo Memmi. So polarizing a discrepancy led, inevitably, to a hesitant reception for the proposed amalgamation, since the 1970s, of the paintings in the “Barna” group with those conventionally attributed to Lippo Memmi.28 Numerous scholars opted to compromise by regarding the enlarged oeuvre as the product of a vaguely defined Memmi family workshop—including the artist’s brother Federico (or Tederigo) and possibly his second brother-in-law, Donato Martini—within which there was little possibility of discerning discrete personalities.29 From this point of view, the five signatures left or said to have been left on paintings by Lippo Memmi were regarded as commercial brands rather than personal indications of authorship.30

Not acknowledged within the abundant and frequently polemical literature on this topic is the realization that the chief distinction between the contested group of paintings formerly divided between Lippo Memmi, on the one hand, and “Barna da Siena,” on the other, is not stylistic but compositional. Works with an inventive composition or displaying an original approach to narrative are placed in the second group while the first group comprises works with conventional or traditional themes and compositions. If this distinction were considered, as it always had been, a function of the artists’ personalities, it would be impossible to believe that a single painter could be responsible for both. If, instead, it is recognized that, for the most part, such differences were conditioned by the demands of patronage rather than the whims of the artist’s creativity, it is easy, indeed inevitable, to recognize a single artistic intelligence, of the highest degree of accomplishment, behind the entire group. The Saint John the Baptist on a faldstool in Altenburg, part of the San Paolo a Ripa d’Arno altarpiece, is fundamentally the same figure as the Saint John the Baptist from the San Gimignano altarpiece in Washington (see fig. 4). Differences between them are largely due to the latter being marginally more mature and considerably less well preserved than the former. The rhythm of their drapery folds and their command of spatial devices are identical, within the greater restrictions of format imposed by the context for which the Washington panel was created. Similarly, the Virgin and Child Enthroned in the Richard Feigen collection (fig. 14), incontestably part of the Barna group, is in all respects the same as the small Virgin and Child Enthroned in Altenburg (fig. 15), signed by Lippo Memmi,31 the fur-lined cloth of honor in the latter no less a tour de force than any of the painterly effects in the former. It follows that differentiating the work of Lippo Memmi from that of Simone Martini must proceed from a full and realistic assessment of Lippo’s polyvalent accomplishments rather than from the conventional perspective regarding him as being merely a lesser-quality imitator of Simone. It is not adequate, or even meaningful, simply to assess the degree to which the work of one is perceived to be an inferior variant of the other.

At least two fundamental differences of artistic temperament may be observed within works attributed either to Simone or Lippo. Simone’s interest in spatial illusion was most fully expressed in the study of single objects or figures. These might be portrayed from stunningly original points of view and realized with remarkable success, but they were frequently integrated into larger compositional ensembles with a casual disregard for the overall cohesion of the scene. Not infrequently, he might include a figure’s hands or wrists seemingly disconnected from any indication of an arm and placed without regard for its logical relationship to the body to which it should notionally be attached. Lippo Memmi, by contrast, was scrupulously obsessive in creating accurate spatial envelopes for his figures and for the props—thrones, cushions, canopies, buildings—in his paintings; likewise, he was meticulous in his application of the rules of foreshortening to figures, their draperies, and the structures that might surround them. In addition, Simone Martini was an adventurous and original colorist. Not only are his choices of hues and his manipulation of color contrasts unique for this period, but also the freedom and looseness with which he brushed these onto his panels or frescoed wall surfaces, both blending and layering, is unparalleled in his generation. Lippo Memmi did not share this predilection. His modeling from light to dark is exceptionally accomplished, but he invariably works within solid areas of local color. His gift is his strength of drawing and the tight control he maintains over his brush at all times. Simone’s handling of the brush is more bravura than disciplined. With these distinctions in mind, it should be apparent that all six lateral panels from the San Gimignano altarpiece are by Lippo Memmi, not Simone Martini, as is the Lucignano d’Arbia Virgin, contrary to current assumptions of scholarship. While it seems unlikely that this panel can be joined physically with the other six, it may well reflect, in general terms, the appearance of the missing center panel of the San Gimignano altarpiece.

Fixed points in the chronology of Lippo Memmi’s expanded oeuvre are numerous, but many of them are imprecise. In 1317 he signed and dated the fresco of the Maestà in the Palazzo del Popolo in San Gimignano. A presumed terminus a quo of 1323 is frequently assigned to the altarpiece of the Glorification of Saint Thomas Aquinas in Santa Caterina in Pisa, close to the date of the saint’s canonization, but in practice, that date could just as easily be a terminus post quem. An eighteenth-century record of the date 1325, said to have been visible alongside Lippo Memmi’s signature beneath the altarpiece from San Paolo a Ripa d’Arno, also in Pisa, has alternately been deemed authoritative and unreliable. It has also been suggested that this date might have been fragmentary and possibly, therefore, reconstructed as anything between 1325 and 1329.32 There can be little doubt on stylistic grounds that the two works from Pisa were painted close in time to each other, so while the evidence for dating them is in the one case inferential and in the other both indirect and variable, there is little reason to reject the evidence outright. The scenes from the New Testament frescoed on the right wall of the nave in the Collegiata at San Gimignano, the works that Lorenzo Ghiberti had first praised as the masterpieces of Barna da Siena, are, by all measures, more mature than either of the Pisan altarpieces. Recent archival scholarship has narrowed a window of opportunity for their execution to between 1337 and 1343. The fragmentary remains of a fresco from San Domenico in Siena testify to Lippo Memmi’s style in the last years of his life, after 1350. Together with his contributions to the 1333 Annunciation altarpiece and a small signed and dated diptych of the same year divided between the Gemäldegalerie, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin,33 and a private collection, this leaves an unusually long and evenly spaced range of reasonably well-documented works to mark the stages of his development.

A majority of scholars assign a vague date of ca. 1330 to the panels of the San Gimignano altarpiece, without specifying a reason for this approximation. Bagnoli argued instead that they must follow closely upon the completion of the Glorification of Saint Thomas Aquinas altarpiece in Pisa, which he felt was probably painted in anticipation of the saint’s canonization, not in response to it, and therefore ca. 1321–23.34 He justified this contention by comparing the type of the Louvre Saint Peter (see fig. 3) to the same saint in Simone’s polyptych painted for the Dominicans of Orvieto in 1320, always assuming that Lippo followed Simone’s example and, as often as not, at no great distance of time. He cited as well the pronounced “Simonesque” and “Gothicizing” qualities of the Washington Saint John the Baptist (see fig. 4) and the Griggs Saint John the Evangelist as evidence of an early date. Pierluigi Leone de Castris felt that the date suggested by Bagnoli (ca. 1323–25) was “precocious,” without, however, specifying how much later he felt it ought to be.35 In support of this latter view, it may be observed that the unusual device incorporated by Lippo Memmi in the Griggs panel of showing the Evangelist dipping his pen in an inkwell as he is poised to write his Gospel also appears in Simone Martini’s painting of Saint Luke the Evangelist now in the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles (fig. 16). That panel is part of a pentaptych that is generally identified as a documented work painted by Simone Martini for the Palazzo Pubblico in Siena in 1326,36 and the question would then arise of whether the gesture was invented by Simone and later imitated by Lippo or vice versa. Bagnoli, however, advanced arguments for disassociating the Getty panel and its companions from the 1326 document, preferring to consider it a work of ca. 1320. It is difficult to decide whether this argument is circular or substantive.

The defining question for dating the panels of the San Gimignano altarpiece seems to be determining whether they precede or follow those of the San Paolo a Ripa d’Arno altarpiece, with which they share so many details of figure type and emotional content. There is an unbroken continuity of effects and idiosyncratic types between the figures in the San Paolo a Ripa d’Arno altarpiece, especially its pinnacles, and the Glorification of Saint Thomas Aquinas altarpiece, none of which recur among the panels of the San Gimignano altarpiece. This continuity has long been recognized by scholars, first in the creation of a so-called Master of the Glorification of Saint Thomas and later in the admission that this painter and “Barna” were one and the same but yet distinct from Lippo Memmi. It is implausible to imagine that the San Gimignano panels—core works within the traditional Memmi corpus—could intervene between the two altarpieces from Pisa. Positioning them instead after the San Paolo a Ripa d’Arno altarpiece explains their greater resemblance to the Santa Massima from the 1333 Annunciation altarpiece or the Madonna del Popolo from Santa Maria dei Servi in Siena, a work plausibly dated in the 1330s. Determining how much later they might have been painted than the San Paolo panels would be an intuitive exercise. —LK

Published References

Venturi, Adolfo. “La Galleria Sterbini a Roma.” In Storia dell’arte italiana 8. Milan: Ulrico Hoepli, 1905., 424; Sirén, Osvald, and Maurice W. Brockwell. Catalogue of a Loan Exhibition of Italian Primitives in Aid of the American War Relief. Exh. cat. New York: F. Kleinberger Galleries, 1917., 126, no. 47; van Marle, Raimond. Simone Martini et les peintres de son école. Strasbourg, France: J. H. E. Heitz, 1920., 24; van Marle, Raimond. The Development of the Italian Schools of Painting. Vol. 2. The Hague: M. Nijhoff, 1924., 173, 184–86; van Marle, Raimond. “Quadri senesi sconosciuti.” La Diana 4 (1929): 307–10., 308, 310n1; Venturi, Lionello. Pitture italiane in America. 2 vols. Milan: Ulrico Hoepli, 1931., pl. 56; Berenson, Bernard. Italian Pictures of the Renaissance: A List of the Principal Artists and Their Works with an Index of Places. Oxford: Clarendon, 1932., 534; Venturi, Lionello. Italian Paintings in America. Trans. Countess Vanden Heuvel and Charles Marriott. 3 vols. New York: E. Weyhe, 1933., no. 70; Berenson, Bernard. Pitture italiane del Rinascimento: Catalogo dei principali artisti e delle loro opera. Trans. Emilio Cecchi. Milan: Ulrico Hoepli, 1936., 459; McCall, George Henry, and William R. Valentiner. Catalogue of European Paintings and Sculpture from 1300–1800: Masterpieces of Art, New York World’s Fair, May to October, 1939. Exh. cat. N.p., 1939., no. 237; Comstock, Helen. “The World’s Fair and Other Exhibitions.” Connoisseur 103 (1939): 275–77., 275–77; Arts of the Middle Ages: A Loan Exhibition. Exh. cat. Boston: Museum of Fine Arts, 1940., no. 52; “The Griggs Collection.” Bulletin of the Associates in Fine Arts at Yale University 13, no. 1 (November 1944): 2–3., 3; Venturi, Lionello. The Rabinowitz Collection. New York: Twin Editions, 1945., pl. 16; “Drawings and Paintings.” Bulletin of the Associates in Fine Arts at Yale University 14, no. 3 (July 1946): 2., 2; “Picture Book Number One: Italian Painting,” special issue, Bulletin of the Associates in Fine Arts at Yale University 15, nos. 1–3 (October 1946): n.p., fig. 17; Comstock, Helen. “The Yale Collection of Italian Paintings.” Connoisseur 118 (September 1946): 45–52., 50; Zeri, Federico. “An Exhibition of Mediterranean Primitives.” Burlington Magazine 94, no. 596 (November 1952): 320–23., 321; Steinweg, Klara. “Beiträge zu Simone Martini und seiner Werkstatt.” Mitteilungen des Kunsthistorischen Institutes in Florenz 7, nos. 3–4 (July 1956): 161–68., 167; Volpe, Carlo. “Precisazioni sul ‘Barna’ e sul ‘Maestro di Palazzo Venezia.’” Arte antica e moderna 10 (April–June 1960): 149–58., 157n10; Coor-Achenbach, Gertrude. “Two Unknown Paintings by the Master of the Glorification of St. Thomas and Some Closely Related Works.” Pantheon 19, no. 3 (1961): 126–35., 127–33; Shapley, Fern Rusk. Paintings from the Samuel H. Kress Collection: Italian Schools, XIII–XV Century. London: Phaidon, 1966., 49; Berenson, Bernard. Italian Pictures of the Renaissance, A List of the Principal Artists and Their Works with an Index of Places: Central Italian and North Italian Schools. 3 vols. London: Phaidon, 1968., 1:269; Bologna, Ferdinando. I pittori alla corte angioina di Napoli, 1266–1414. Rome: Bozzi, 1969., 335n7; Seymour, Charles, Jr. Early Italian Paintings in the Yale University Art Gallery. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1970., 90–93, no. 64; Fredericksen, Burton B., and Federico Zeri. Census of Pre-Nineteenth-Century Italian Paintings in North American Public Collections. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1972., 600; Fahy, Everett. Review of Paintings from the Samuel H. Kress Collection: Italian Schools XII–XV Century, by Fern Rusk Shapley; Paintings from the Samuel H. Kress Collection: Italian Schools XV–XVI Century, by Fern Rusk Shapley; Early Italian Paintings in the Yale University Art Gallery, by Charles Seymour, Jr.; and Italian Primitives: The Case History of a Collection and Its Conservation, by Charles Seymour, Jr. Art Bulletin 56, no. 2 (June 1974): 283–85., 283–84; De Benedictis, Cristina. “A proposito di un libro su Buffalmacco.” Antichità viva 13, no. 2 (March–April 1974): 3–10., 8; Mallory, Michael. “An Altarpiece by Lippo Memmi Reconsidered.” Metropolitan Museum Journal 9 (1974): 187–202., 187–88; Mallory, Michael. “Thoughts Concerning the ‘Master of the Glorification of St. Thomas.’” Art Bulletin 57, no. 1 (March 1975): 9–20., 18–20; De Benedictis, Cristina. “Il polittico della Passione di Simone Martini e una proposta per Donato.” Antichità viva 15, no. 6 (1976): 3–11., 7–8; Caleca, Antonino. “Tre polittici di Lippo Memmi: Un’ipotesi sul Barna e la bottega di Simone e Lippo, I.” Critica d’arte 41 (1976): 49–59., 53; Caleca, Antonino. “Tre polittici di Lippo Memmi: Un’ipotesi sul Barna e la bottega di Simone e Lippo, II.” Critica d’arte 42 (1977): 55–80., 70; Torriti, Piero. La Pinacoteca Nazionale di Siena. Vol. 1, I dipinti dal XII al XV secolo. Genoa: Sagep, 1977., 54–56; Maginnis, Hayden B. J. “The Literature of Sienese Trecento Painting, 1945–1975.” Zeitschrift für Kunstgeschichte 40, nos. 3–4 (1977): 276–309., 289; Meiss, Millard. “Notes on a Dated Diptych by Lippo Memmi.” In Scritti di storia dell’arte in onore di Ugo Procacci, ed. Maria Grazia Ciardi Duprè Dal Poggetto and Paolo Dal Poggetto, 1:137–39. Milan: Electa, 1977., 1:139; Michel Laclotte, in Ressort, Claudie, ed. Retables italiens du XIIIe au XVe siècle. Exh. cat. Paris: Éditions de la Réunion des musées nationaux, 1978., 19; Shapley, Fern Rusk. Catalogue of the Italian Paintings: National Gallery of Art. 2 vols. Washington, D.C.: National Gallery of Art, 1979., 1:331; De Benedictis, Cristina. La pittura senese, 1330–1370. Florence: Salimbeni, 1979., 93; Zeri, Federico, and Elizabeth E. Gardner. Italian Paintings: A Catalogue of the Collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art; Sienese and Central Italian Schools. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1980., 50–52; Christiansen, Keith. “Fourteenth-Century Italian Altarpieces.” Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin 40, no. 1 (Summer 1982): 1–56., 26–27; Marianne Lonjon, in L’art gothique siennois: Enluminure, peinture, orfèvrerie, sculpture. Exh. cat. Florence: Centro Di, 1983., 142; Giovanni Previtali, in Bagnoli, Alessandro, and Luciano Bellosi, eds. Simone Martini e “chompagni.” Exh. cat. Siena: Centro Di, 1985., 28; Conti, Alessandro. “Simone Martini e ‘chompagni’: Siena, Pinacoteca Nazionale, 27 marzo–31 ottobre, 1985.” Bollettino d’arte 71, nos. 35–36 (1986): 101–8., 102; Tartuferi, Angelo. “Appunti su Simone Martini e ‘chompagni.’” Arte cristiana 74, no. 713 (March–April 1986): 79–92., 86, 92n32; Boskovits, Miklós. Frühe italienische Malerei: Gemäldegalerie Berlin, Katalog der Gemälde. Berlin: Mann, 1988., 74–75; Martindale, Andrew. Simone Martini. Oxford: Phaidon, 1988., 29, 59; Previtali, Giovanni. “Introduzione ai problemi della bottega di Simone Martini.” In Simone Martini: Atti del convegno, Siena, 27, 28, 29 marzo 1985, ed. Luciano Bellosi, 151–66. Florence: Centro Di, 1988., 160–61, 166n22, 26; Cannon, Joanna. “The Creation, Meaning, and Audience of the Early Sienese Polyptych: Evidence from the Friars.” In Italian Altarpieces, 1250–1550: Function and Design, ed. Eve Borsook and Fiorella Superbi Gioffredi, 41–79. Oxford: Clarendon, 1994., 60–62; Frinta, Mojmír S. Punched Decoration on Late Medieval Panel and Miniature Painting. Vol. 1, Catalogue Raisonné of All Punch Shapes. Prague: Maxdorf, 1998., 78, 189, 247, 298, 310, 400, 423, 516; Bagnoli, Alessandro. La Maestà di Simone Martini. Cinisello Balsamo, Milan: Silvana, 1999., 142, 151n184; Dean, Clay. A Selection of Early Italian Paintings from the Yale University Art Gallery. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 2001., 13, 22–23, no. 4; Leone de Castris, Pierluigi. Simone Martini. Milan: Federico Motta, 2003., 181, 218n49; Lonjon, Marianne. “Précisions sur la provenance du retable dit ‘de Colle di Val d’Elsa’ de Lippo Memmi.” La revue des musées de France 2 (April 2006): 31–40., 34, 38n1, 39n13; Daniela Parenti, in Boskovits, Miklós, and Johannes Tripps, eds. Maestri senesi e toscani nel Lindenau-Museum di Altenburg. Exh. cat. Siena: Protagon, 2008., 34, 37n24; Miklós Boskovits, in Bellosi, Luciano, ed. La collezione Salini: Dipinti, sculture e oreficerie dei secoli XII, XIII, XIV e XV. Vol. 1, Pittura. Florence: Centro Di, 2009., 147–48; Spannocchi, Sabina. “Lippo e Tederico Memmi.” In La Collegiata di San Gimignano: L’architettura, i cicli pittorici murali e i loro restauri, ed. Alessandro Bagnoli, 445–58. Siena: Protagon, 2009., 450; Boskovits, Miklós. Italian Paintings of the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries. Washington, D.C.: National Gallery of Art, 2016. NGA Online Editions, https://purl.org/nga/collection/catalogue/italian-paintings-of-the-thirteenth-and-fourteenth-centuries., 203–14

Notes

-

Venturi, Adolfo. “La Galleria Sterbini a Roma.” In Storia dell’arte italiana 8. Milan: Ulrico Hoepli, 1905., 424. ↩︎

-

Venturi, Lionello. Pitture italiane in America. 2 vols. Milan: Ulrico Hoepli, 1931., pl. 56; Berenson, Bernard. Italian Pictures of the Renaissance: A List of the Principal Artists and Their Works with an Index of Places. Oxford: Clarendon, 1932., 534; Venturi, Lionello. Italian Paintings in America. Trans. Countess Vanden Heuvel and Charles Marriott. 3 vols. New York: E. Weyhe, 1933., no. 70; and Berenson, Bernard. Pitture italiane del Rinascimento: Catalogo dei principali artisti e delle loro opera. Trans. Emilio Cecchi. Milan: Ulrico Hoepli, 1936., 459. ↩︎

-

van Marle, Raimond. Simone Martini et les peintres de son école. Strasbourg, France: J. H. E. Heitz, 1920., 24; and van Marle, Raimond. The Development of the Italian Schools of Painting. Vol. 2. The Hague: M. Nijhoff, 1924., 173, 184–86. ↩︎

-

Comstock, Helen. “The World’s Fair and Other Exhibitions.” Connoisseur 103 (1939): 275–77., 275–77; and Comstock, Helen. “The Yale Collection of Italian Paintings.” Connoisseur 118 (September 1946): 45–52., 50. ↩︎

-

Zeri, Federico. “An Exhibition of Mediterranean Primitives.” Burlington Magazine 94, no. 596 (November 1952): 320–23., 321. ↩︎

-

Seymour, Charles, Jr. Early Italian Paintings in the Yale University Art Gallery. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1970., 90–93. ↩︎

-

Berenson, Bernard. Pitture italiane del Rinascimento: Catalogo dei principali artisti e delle loro opera. Trans. Emilio Cecchi. Milan: Ulrico Hoepli, 1936., 459; and Berenson, Bernard. Italian Pictures of the Renaissance, A List of the Principal Artists and Their Works with an Index of Places: Central Italian and North Italian Schools. 3 vols. London: Phaidon, 1968., 1:269. ↩︎

-

Bagnoli, Alessandro. La Maestà di Simone Martini. Cinisello Balsamo, Milan: Silvana, 1999., 142, 151n184. ↩︎

-

Steinweg, Klara. “Beiträge zu Simone Martini und seiner Werkstatt.” Mitteilungen des Kunsthistorischen Institutes in Florenz 7, nos. 3–4 (July 1956): 161–68., 167; and De Benedictis, Cristina. “A proposito di un libro su Buffalmacco.” Antichità viva 13, no. 2 (March–April 1974): 3–10., 8. ↩︎

-

Vasari, Giorgio. Le vite de’ più eccellenti pittori, scultori ed architettori. With new annotations and comments by Gaetano Milanesi. 9 vols. Florence: G. C. Sansoni, 1878–85., 1:555. ↩︎

-

Musée de la Chartreuse, Douai, France, inv. no. 1135; and Lindenau-Museum Altenburg, Germany, inv. nos. 44–45. See Coor-Achenbach, Gertrude. “Two Unknown Paintings by the Master of the Glorification of St. Thomas and Some Closely Related Works.” Pantheon 19, no. 3 (1961): 126–35., 127–33. ↩︎

-

Mallory, Michael. “An Altarpiece by Lippo Memmi Reconsidered.” Metropolitan Museum Journal 9 (1974): 187–202., 187–88. ↩︎

-

For the Saint John the Baptist, see Lindenau-Museum Altenburg, Germany, inv. no. 42; for the Saint Andrew, see Museo Nazionale di San Matteo, Pisa. ↩︎

-

Bagnoli, Alessandro. La Maestà di Simone Martini. Cinisello Balsamo, Milan: Silvana, 1999., 151n184. See also Lonjon, Marianne. “Précisions sur la provenance du retable dit ‘de Colle di Val d’Elsa’ de Lippo Memmi.” La revue des musées de France 2 (April 2006): 31–40., 34–35. ↩︎

-

Manuscript opinion reported in Zeri, Federico, and Elizabeth E. Gardner. Italian Paintings: A Catalogue of the Collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art; Sienese and Central Italian Schools. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1980., 51. ↩︎

-

van Marle, Raimond. Simone Martini et les peintres de son école. Strasbourg, France: J. H. E. Heitz, 1920., 24. ↩︎

-

De Benedictis, Cristina. “A proposito di un libro su Buffalmacco.” Antichità viva 13, no. 2 (March–April 1974): 3–10., 8. ↩︎

-

Mallory, Michael. “An Altarpiece by Lippo Memmi Reconsidered.” Metropolitan Museum Journal 9 (1974): 187–202., 187–88. ↩︎

-

Maginnis, Hayden B. J. “The Literature of Sienese Trecento Painting, 1945–1975.” Zeitschrift für Kunstgeschichte 40, nos. 3–4 (1977): 276–309., 289. ↩︎

-

Boskovits, Miklós. Frühe italienische Malerei: Gemäldegalerie Berlin, Katalog der Gemälde. Berlin: Mann, 1988., 74–75. ↩︎

-

Boskovits, Miklós. Italian Paintings of the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries. Washington, D.C.: National Gallery of Art, 2016. NGA Online Editions, https://purl.org/nga/collection/catalogue/italian-paintings-of-the-thirteenth-and-fourteenth-centuries., 211n24. ↩︎

-

The author is grateful to Elena Pinzauti, Machtelt Israëls, and Carl Strehlke for careful measurements of the Lucignano Virgin and the Saint Francis and Saint Louis of Toulouse in the Pinacoteca Nazionale, Siena. ↩︎

-

Gallerie degli Uffizi, Florence, inv. no. 451–53. ↩︎

-

Vasari, Giorgio. Le vite de’ più eccellenti pittori, scultori ed architettori. With new annotations and comments by Gaetano Milanesi. 9 vols. Florence: G. C. Sansoni, 1878–85., 1:554, 558–59. ↩︎

-

An important breakthrough in disentangling each artist’s contribution to this altarpiece was published by Miklós Boskovits, following observations first advanced by Klara Steinweg. See Boskovits, Miklós. “Sul trittico di Simone Martini e di Lippo Memmi.” Arte cristiana 74 (1986): 69–78., 69–78; and Steinweg, Klara. “Beiträge zu Simone Martini und seiner Werkstatt.” Mitteilungen des Kunsthistorischen Institutes in Florenz 7, nos. 3–4 (July 1956): 161–68., 161–68. For these writers, Lippo’s contribution was largely confined to the figure of Santa Massima (formerly thought to be Santa Giulitta) in the right-lateral panel of the altarpiece. This contention was expanded and refined by Andrea De Marchi, who added large parts of the figure of the Virgin in the central panel to Lippo’s share; see De Marchi, Andrea. “La parte di Simone e la parte di Lippo.” Nuovi studi 12 (2006): 5–24., 5–24. While De Marchi’s arguments for attributing various portions of work in the Annunciation altarpiece to one artist or the other are wholly persuasive, his efforts to extend the corpus of their collaborations to a diptych in the Museo Horne, Florence, inv. nos. 55–56, and another divided between the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (inv. no. 43.98.6, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/437063), and the Musée du Louvre, Paris (inv. no. RF 1984 31, https://collections.louvre.fr/en/ark:/53355/cl010061668), are not. ↩︎

-

Vasari, Giorgio. Le vite de’ più eccellenti pittori, scultori ed architettori. Ed. Gaetano Milanesi. 9 vols. Florence: G. C. Sansoni, 1906., 1:554. ↩︎

-

Volpe, Carlo. “Precisazioni sul ‘Barna’ e sul ‘Maestro di Palazzo Venezia.’” Arte antica e moderna 10 (April–June 1960): 149–58., 149–50. Carlo Volpe’s characterization of Lippo Memmi was borrowed from Pietro Toesca, in Toesca, Pietro. Il trecento. Turin: Unione Tipografico Editrice Torinese, 1951., 554. ↩︎

-

For a concise summary of the long, often repetitive, sometimes contentious bibliography addressing the amalgamation of Lippo and Barna, see Daniela Parenti, in Boskovits, Miklós, and Johannes Tripps, eds. Maestri senesi e toscani nel Lindenau-Museum di Altenburg. Exh. cat. Siena: Protagon, 2008., 28–37. ↩︎

-

The most elaborate exposition of the scope of this family workshop, as well as a detailed and confident division of hands within it, is to be found in Machtelt Israëls, “The Memmi-Martini Compagnia,” in Strehlke, Carl Brandon, and Machtelt Brüggen Israëls, eds. The Bernard and Mary Berenson Collection of European Paintings at I Tatti. Milan: Officina Libraria, 2015., 441–43. ↩︎

-

See Laurence Kanter, in Kanter, Laurence, and John Marciari. Italian Paintings from the Richard L. Feigen Collection. Exh. cat. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 2010., 42–48, for a review of the problems associated with these signatures. Though the evidentiary value of these signatures is relative rather than absolute, the present author now believes that the distinctions between Lippo Memmi and supposed members of his family workshop are overscrupulous and, in most cases, exaggerated. The “Barna” group, in particular, all seem to be works by Lippo Memmi and an indication of his true stature within the development of Sienese painting. One possible exception to this regrouping is the Casciana Alta altarpiece, which seems to be the work of Pisan assistants of Lippo Memmi. A Sienese document of 1327 cites a certain “Giovanni suo [i.e., Lippo’s] discepolo di Pisa”; see Hueck, Irene. “‘L’Annunciazione e Santi’ di Simone Martini e Lippo Memmi.” In Simone Martini e “l’Annunciazione” degli Uffizi, ed. Alessandro Cecchi, 11–33. Cinisello Balsamo, Milan: Silvana, 2001., 19. It may be possible to identify this “Giovanni” with Giovanni di Nicola da Pisa, whose style is closely related to that of the Casciana Alta altarpiece. ↩︎

-

Lindenau-Museum Altenburg, Germany, inv. no. 43. ↩︎

-

Caleca, Antonino. “Tre polittici di Lippo Memmi: Un’ipotesi sul Barna e la bottega di Simone e Lippo, I.” Critica d’arte 41 (1976): 49–59., 1977; and Daniela Parenti, in Boskovits, Miklós, and Johannes Tripps, eds. Maestri senesi e toscani nel Lindenau-Museum di Altenburg. Exh. cat. Siena: Protagon, 2008., 30. ↩︎

-

Inv. no. 1081 A. ↩︎

-

Bagnoli, Alessandro. La Maestà di Simone Martini. Cinisello Balsamo, Milan: Silvana, 1999., 142, 151n184. ↩︎

-

Leone de Castris, Pierluigi. Simone Martini. Milan: Federico Motta, 2003., 181, 218n49. ↩︎

-

Boskovits, Miklós. “A Dismembered Polyptych: Lippo Vanni and Simone Martini.” Burlington Magazine 116, no. 856 (July 1974): 367–76., 367–76; and Christiansen, Keith. “Simone Martini’s Altar-Piece for the Commune of Siena.” Burlington Magazine 136, no. 1092 (March 1994): 148–60., 148–60. ↩︎