Icilio Federico Joni (1866–1946), Siena; Dan Fellows Platt (1873–1937), Englewood N.J., 1909; Prince Vittorio Emanuele(?), count of Turin (1870–1946);1 Maitland Fuller Griggs (1872–1943), New York, by 1925

The panel support, of a vertical wood grain, is 3.5 centimeters deep and has been heavily waxed on the reverse. It may have been thinned slightly, as the dowel holes on both lateral edges are set significantly closer to the back than to the front of the panel. These holes are 15 millimeters in diameter and are spaced 57.5 centimeters apart on the right edge—5 centimeters from the top and 10 centimeters from the bottom; they are 53 centimeters apart on the left edge—5 centimeters from the top and 15 centimeters from the bottom. Repairs measuring 1 centimeter wide have been integrated into the left and right edges of the spandrels, but the arch moldings are intact. This painting was not cleaned in the treatment of 1964 to which the related Saint Peter was subjected, and its paint surface, though darkened by an old and discolored varnish, is pristine. An irregular margin of damage up to 4 centimeters wide along the full length of the left, bottom, and right edges has been regilt or repainted.

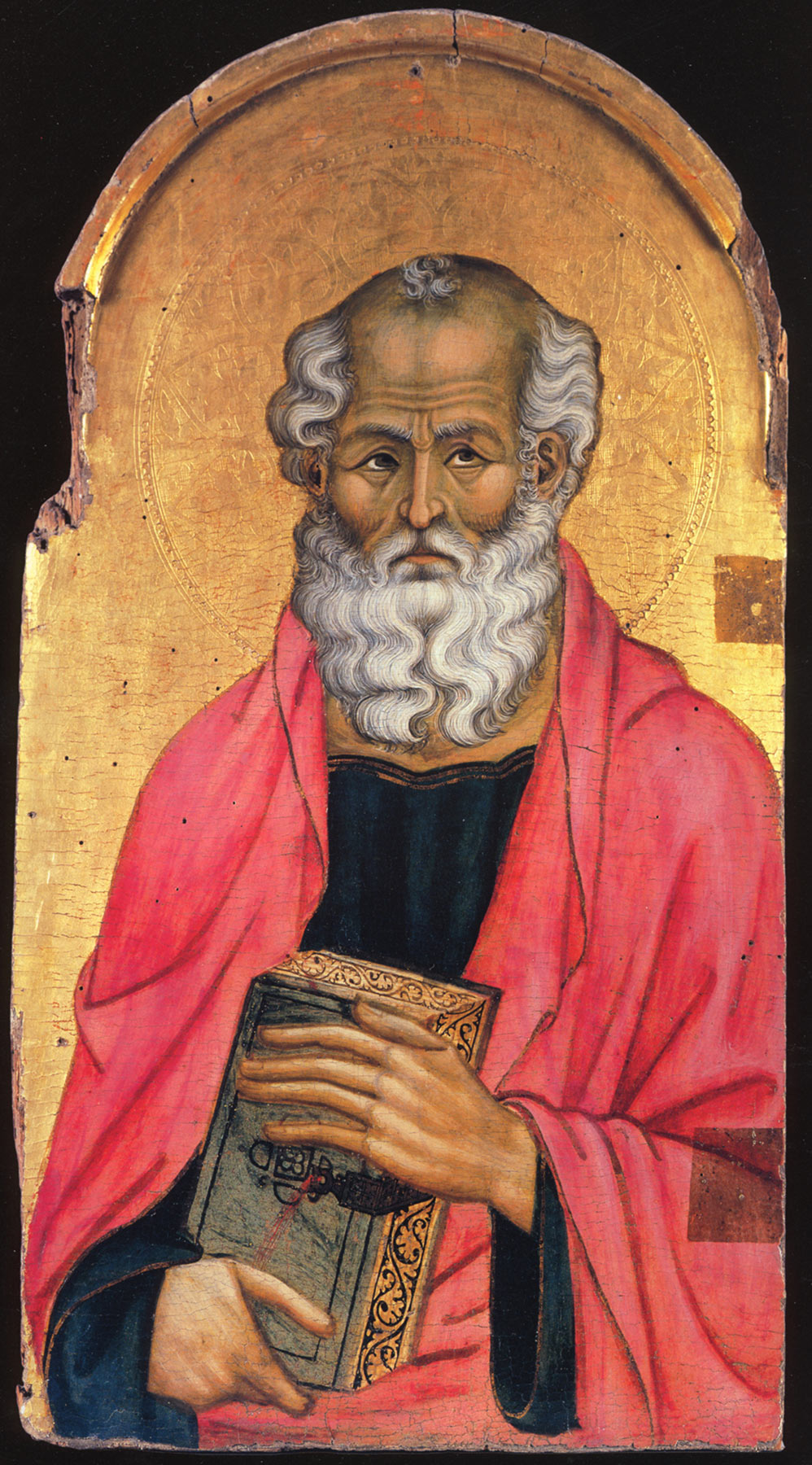

This panel representing Saint John the Baptist and the related Saint Peter were unknown in the early years of the twentieth century when the first attempts were made to reconstruct an artistic personality subsequently identified by the conventional name Master of Città di Castello.2 They were first published as the work of Ugolino di Nerio when they entered the collection of Maitland Griggs,3 but they have consistently and correctly been acknowledged as cornerstones of the late career of the Città di Castello Master since they were first so identified by Richard Offner in 1926.4 Though the attribution and relative dating of the panels have never been in doubt, minor differences of opinion have emerged concerning the exact reconstruction of the altarpiece complex of which they once formed part and of the specific span of years possibly embraced by the late career of the Master of Città di Castello. These disagreements, in turn, reflect lingering uncertainty over the precise contours of the painter’s total oeuvre: notwithstanding the fact that he is widely appreciated as the most emotive and distinctively, almost eccentrically, mannered of Duccio’s recognized followers and contemporaries, works associated with his name by some scholars are divided into two, three, or even four distinct personalities by others.5

Raimond van Marle, when he first brought the Griggs panels to public attention, perceptively associated them with a panel in the Lanckoronski collection, then in Vienna, representing Saint Francis (fig. 1), as fragments of a single altarpiece. This suggestion was not acknowledged by Offner when he first advanced the correct attribution for the Griggs Saints, and it was ignored by Sherwood Fehm in his otherwise highly detailed study of the two panels at Yale.6 Luisa Vertova and Bernard Berenson accepted the relationship of the Griggs panels with the Lanckoronski Saint Francis, as did Federico Zeri, who added a related figure of Saint Anthony of Padua in the collection of Amedeo Lia at La Spezia (fig. 2).7 These four saints have not subsequently been questioned as belonging to a single altarpiece until the most recent publication of the Lanckoronski panel, where it is claimed that the Saint Francis must be part of a different ensemble on the mistaken assumptions that, first, its frame is entirely original and therefore it is significantly different in size from the other panels and, second, it is in a superior state of preservation, revealing subtle stylistic differences.8 In reality, the lower half of the Lanckoronski Saint Francis is largely, if not entirely, modern repaint.

A further note of dissension in this proposed reconstruction involves Fehm’s assertion that a Virgin and Child by the Master of Città di Castello in Copenhagen (fig. 3) was in all likelihood the center panel of the altarpiece from which the Griggs Saints originated and that the latter both stood on the left side of the original complex. Fehm’s contention was based on measurements of dowel holes present on the lateral edges of the Copenhagen and Yale panels, the spacing of which argued for placing the figure of the Baptist immediately to the left of the Virgin and the figure of Saint Peter immediately to the left of the Baptist. This reconstruction was recently accepted by Andrea De Marchi.9 Vertova, who at the time of writing was seemingly not aware of Fehm’s research (though she did cite and apparently accept his findings in a footnote, without acknowledging that they contradict the claims advanced in her text), believed the Copenhagen Virgin to be the product of an earlier phase in the Master’s career, proposing instead that a fragmentary Virgin and Child from the church of Santa Cecilia at Crevole was more closely related to the Yale panels. Vertova went so far as to suggest that sufficient differences could be discerned between the two panels at Yale that they could perhaps be considered surviving remnants of two different triptychs, the Saint Peter being as much like the Lanckoronski Saint Francis as both are unlike the Saint John the Baptist.

While no later author has accepted this last suggestion, Zeri did agree with Vertova that the Copenhagen Virgin and Yale Saints are stylistically unrelated and therefore that Fehm’s purportedly scientific demonstration of their contiguity was irrelevant, probably the result of nothing more than the coincidence in general scale of numerous Sienese altarpieces.10 Furthermore, in adding the Lia Saint Anthony of Padua to the reconstruction, he pointed out that the Yale Saint Peter cannot originally have stood to the left of the Baptist since the outermost pair of saints in this altarpiece must have been the two Franciscans, based on repeatedly similar arrangements in other intact altarpieces. Joanna Cannon agreed that Saints Francis and Anthony of Padua must have stood outermost among the lateral panels in the complex.11 Although she accepted the Copenhagen Virgin as the putative center of the structure, she correctly pointed out that Fehm’s measurements do not correspond exactly at any point between or among the panels. She therefore arranged the five panels in a hypothetical pentaptych—reading, from left to right, Saint Francis, Saint John the Baptist, Virgin and Child, Saint Peter, Saint Anthony of Padua—but without any conviction that this sequence was irrefutably correct.

It has hitherto escaped notice that the “Griggs altarpiece” is more likely to have been a heptaptych than a pentaptych. Alessandro Bagnoli, in his well-argued essay on the Crevole altarpiece by the Master of Città di Castello, published a previously unknown half-length image of Saint John the Evangelist in the Salini Collection at the Castello di Gallico (fig. 4), later catalogued by Federica Siddi as the only surviving lateral panel of an unidentified polyptych.12 Although it is exceptionally close in style to the Griggs, Lanckoronski, and Lia Saints, the Salini Evangelist is considerably smaller (59.2 × 31.5 cm) than they are and lacks the characteristic triad of punched dots that line the outer engraved rim of the saint’s halo, which is also positioned slightly lower within the picture field than it is in the other four panels. The Salini panel, however, has been cropped more aggressively than any of the other panels discussed so far, eliminating the topmost molding of its engaged frame (a surviving barb indicates that such a molding has been removed), all of the area along the sides of the panel that in the others stood beneath engaged spires in the superstructure, and the entire unpainted area at the bottom of the panel that once underlay and supported the engaged outer frame. Excluding the corresponding areas in the Griggs Saint Peter leaves a remaining field measuring 59.4 by 32.0 centimeters, so close to the present measurements of the Salini panel that it is essential to discuss the probability of their having once been companions. As a complement to Saint John the Baptist, Saint John the Evangelist would have stood immediately to the right of the Virgin and Child. Evidence of dowel holes has been lost along the left edge of the Salini panel; two holes on the right edge of the panel remain but their distance apart is not recorded. By implication, Saint Peter, standing to the right of Saint John the Evangelist, would have been complemented by a missing panel probably representing Saint Paul, positioned to the left of Saint John the Baptist. Saints Francis (left) and Anthony of Padua (right) would then have completed the structure in the outermost panels (fig. 5).

Several important Sienese altarpieces destined for Franciscan churches follow a similar heptaptych structure. These include the high altarpiece from Santa Croce in Florence by Ugolino da Siena, the principle surviving panels of which are now in the Gemäldegalerie, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin,13 and the National Gallery, London;14 another, largely intact altarpiece by Ugolino now in the Clark Art Institute, Williamstown, Massachusetts;15 and a dispersed altarpiece by Lippo Memmi (see Lippo Memmi, Saint John the Evangelist, inv. no. 1943.239) reasonably supposed to have been painted for the church of San Francesco in San Gimignano. These are all believed to have been executed close to or shortly after 1320. While it is not possible to advance a proposal for the ultimate provenance of the heptaptych by the Master of Città di Castello, a date for it within the same range of years is plausible. It has until now been agreed only that these panels must have been among the last, most floridly calligraphic, least archaizing works by the artist, but few scholars have agreed on whether this hypothetical late career might have occurred in the first, second, third, or even fourth decade of the fourteenth century, based on whether the Master of Città di Castello was considered a contemporary or a second-generation follower of Duccio. Although consensus is still lacking, recent scholars generally concur in describing the artist as a slightly younger contemporary of Duccio and among the first painters to reflect the influence of that master’s pictorial innovations. De Marchi, who dates the “Griggs altarpiece” to the second decade of the fourteenth century, has recently advanced the intriguing proposal that the Master of Città di Castello might be identifiable with the painter Nerio di Ugolino, father of three other Sienese painters: Ugolino di Nerio,16 Guido di Nerio, and Muccio di Nerio.17 Nerio di Ugolino was mentioned as a painter in two documents of 1311 and recorded as having died between 1317 and 1318. Although based on a hypothetical reconstruction of an only partially legible signature, De Marchi’s proposal is eminently plausible and supports the difficulty of dating any of the known works by the Master of Città di Castello as late as 1320. In the case of the present altarpiece, the inclusion of Saint Anthony of Padua rather than Saint Louis of Toulouse—who is present in the other three Franciscan structures mentioned above—must be due to its having preceded the latter’s canonization in 1317. —LK

Published References

van Marle, Raimond. “Dipinti sconosciuti della scuola di Duccio.” Rassegna d’arte senese 19 (1926): 3–6., 4, fig. 5; Offner, Richard. “Two Sienese Panels.” Bulletin of the Associates in Fine Arts at Yale University 1, no. 1 (March 1926): 5–7., 5–7; Berenson, Bernard. Italian Pictures of the Renaissance: A List of the Principal Artists and Their Works with an Index of Places. Oxford: Clarendon, 1932., 344; Brandi, Cesare. Duccio. Florence: Vallecchi, 1951., 149; Fehm, Sherwood A., Jr. “A Pair of Panels by the Master of Città di Castello and a Reconstruction of Their Original Altarpiece.” Yale University Art Gallery Bulletin 31, no. 2 (Spring 1967): 14–27., 16–27; Vertova, Luisa. “What Goes with What?” Burlington Magazine 109, no. 777 (December 1967): 668–74., 668–71, fig. 7; Berenson, Bernard. Italian Pictures of the Renaissance, A List of the Principal Artists and Their Works with an Index of Places: Central Italian and North Italian Schools. 3 vols. London: Phaidon, 1968., 1:249; Seymour, Charles, Jr. Early Italian Paintings in the Yale University Art Gallery. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1970., 84–86, nos. 59–60; Fredericksen, Burton B., and Federico Zeri. Census of Pre-Nineteenth-Century Italian Paintings in North American Public Collections. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1972., 600; Charles Seymour, Jr., in Seymour, Charles, Jr., et al. Italian Primitives: The Case History of a Collection and Its Conservation. Exh. cat. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1972., 44–45, no. 37, figs. 37a–c; Zeri, Federico. “Addendum al Maestro di Città di Castello.” In Diari di Lavoro, 2:8–10. Turin: Giulio Einaudi, 1976., 2:8–10; Torriti, Piero. La Pinacoteca Nazionale di Siena. Vol. 1, I dipinti dal XII al XV secolo. Genoa: Sagep, 1977., 66; Stubblebine, James. Duccio di Buoninsegna and His School. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1979., 88–89; Cannon, Joanna. “The Creation, Meaning, and Audience of the Early Sienese Polyptych: Evidence from the Friars.” In Italian Altarpieces, 1250–1550: Function and Design, ed. Eve Borsook and Fiorella Superbi Gioffredi, 41–79. Oxford: Clarendon, 1994., 60–62, pl. 53; Zeri, Federico, and Andrea G. De Marchi. Dipinti: La Spezia, Museo Civico Amedeo Lia. Cataloghi del Museo Civico Amadeo Lia 3. Cinisello Balsamo, Milan: Silvana, 1997., 193–94; Freuler, Gaudenz. “Duccio et ses contemporains: Le Maître de Città di Castello.” Revue de l’art 134, no. 4 (2001): 27–50., 45n39; Alessandro Bagnoli, in Bagnoli, Alessandro, Roberto Bartalini, Luciano Bellosi, and Michel Laclotte, eds. Duccio: Alle origini della pittura senese. Exh. cat. Cinisello Balsamo, Milan: Silvana, 2003., 288–89, 298; Federica Siddi, in Bellosi, Luciano, ed. La collezione Salini: Dipinti, sculture e oreficerie dei secoli XII, XIII, XIV e XV. Vol. 1, Pittura. Florence: Centro Di, 2009., 69, 73; Maria Skubiszewska, in Skubiszewska, Maria, and Kazimierz Kuczman. Paintings from the Lanckoronski Collection from the 14th through 16th Centuries in the Collections of the Wawel Royal Castle. Kraków, Poland: Wawel Royal Castle, 2010., 144–46; De Marchi, Andrea. Un incunabolo della nuova pittura senese alla fine del duecento, alle radici del Maestro di Città di Castello (Nerio di Ugolino?). Florence: Mandragora, 2022., 59, 63, 78n39, figs. 98, 106

Notes

-

Charles Seymour, Jr., referred to a Griggs record (not traceable) mentioning the duke of Turin; see Seymour, Charles, Jr. Early Italian Paintings in the Yale University Art Gallery. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1970., 84. ↩︎

-

Perkins, F. Mason. “Alcuni appunti sulla Galleria delle Belle Arti di Siena.” Rassegna d’arte senese 4 (1908): 48–61., 51–52; Krohn, Mario. Italienske Billeder i Danmark. Copenhagen: Gyldendal, 1910., 4–8; and De Nicola, Giacomo. “Duccio di Buoninsegna and His School in the Mostra di Duccio at Siena.” Burlington Magazine 22, no. 117 (December 1912): 138–39, 142–43, 145–47., 147. ↩︎

-

van Marle, Raimond. “Dipinti sconosciuti della scuola di Duccio.” Rassegna d’arte senese 19 (1926): 3–6., 4, fig. 5. ↩︎

-

Offner, Richard. “Two Sienese Panels.” Bulletin of the Associates in Fine Arts at Yale University 1, no. 1 (March 1926): 5–7., 5–7. ↩︎

-

See Bagnoli, Alessandro. “Alle origini della pittura senese: Prime ossevazioni sul ciclo dei dipinti murali.” In Sotto il duomo di Siena: Scoperte archeologiche, architettoniche e figurative, ed. Roberto Guerrini and Max Seidel, 107–47. Cinisello Balsamo, Milan: Silvana, 2003., 314–26; and Boskovits, Miklós. Italian Paintings of the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries. Washington, D.C.: National Gallery of Art, 2016. NGA Online Editions, https://purl.org/nga/collection/catalogue/italian-paintings-of-the-thirteenth-and-fourteenth-centuries., 262–73. ↩︎

-

Fehm, Sherwood A., Jr. “A Pair of Panels by the Master of Città di Castello and a Reconstruction of Their Original Altarpiece.” Yale University Art Gallery Bulletin 31, no. 2 (Spring 1967): 14–27., 16–27. ↩︎

-

Vertova, Luisa. “What Goes with What?” Burlington Magazine 109, no. 777 (December 1967): 668–74., 668–71, fig. 7; Berenson, Bernard. Italian Pictures of the Renaissance, A List of the Principal Artists and Their Works with an Index of Places: Central Italian and North Italian Schools. 3 vols. London: Phaidon, 1968., 1:249; and Zeri, Federico. “Addendum al Maestro di Città di Castello.” In Diari di Lavoro, 2:8–10. Turin: Giulio Einaudi, 1976., 2:8–10. ↩︎

-

Maria Skubiszewska, in Skubiszewska, Maria, and Kazimierz Kuczman. Paintings from the Lanckoronski Collection from the 14th through 16th Centuries in the Collections of the Wawel Royal Castle. Kraków, Poland: Wawel Royal Castle, 2010., 144–46. ↩︎

-

De Marchi, Andrea. Un incunabolo della nuova pittura senese alla fine del duecento, alle radici del Maestro di Città di Castello (Nerio di Ugolino?). Florence: Mandragora, 2022., 63. ↩︎

-

Zeri, Federico. “Addendum al Maestro di Città di Castello.” In Diari di Lavoro, 2:8–10. Turin: Giulio Einaudi, 1976., 2:9–10. ↩︎

-

Cannon, Joanna. “The Creation, Meaning, and Audience of the Early Sienese Polyptych: Evidence from the Friars.” In Italian Altarpieces, 1250–1550: Function and Design, ed. Eve Borsook and Fiorella Superbi Gioffredi, 41–79. Oxford: Clarendon, 1994., 60–62, pl. 53. ↩︎

-

Bagnoli, Alessandro. “Alle origini della pittura senese: Prime ossevazioni sul ciclo dei dipinti murali.” In Sotto il duomo di Siena: Scoperte archeologiche, architettoniche e figurative, ed. Roberto Guerrini and Max Seidel, 107–47. Cinisello Balsamo, Milan: Silvana, 2003., 288–89, 298; and Federica Siddi, in Bellosi, Luciano, ed. La collezione Salini: Dipinti, sculture e oreficerie dei secoli XII, XIII, XIV e XV. Vol. 1, Pittura. Florence: Centro Di, 2009., 69, 73. ↩︎

-

Inv. nos. 1635, https://id.smb.museum/object/864423; 1635A–E, https://id.smb.museum/object/864430, https://id.smb.museum/object/864431, https://id.smb.museum/object/864438, https://id.smb.museum/object/864439, https://id.smb.museum/object/864437. ↩︎

-

Inv. nos. NG1188–89; NG3473; NG3375–78; NG4191; NG6484–86. ↩︎

-

Inv. no. 1962.148, https://www.clarkart.edu/ArtPiece/Detail/Virgin-and-Child-with-Saints-Francis,-Andrew,-(1). ↩︎

-

See Yale University Art Gallery, inv. no. 1959.15.17, https://artgallery.yale.edu/collections/objects/43510. ↩︎

-

De Marchi, Andrea. Un incunabolo della nuova pittura senese alla fine del duecento, alle radici del Maestro di Città di Castello (Nerio di Ugolino?). Florence: Mandragora, 2022., 70–72, 78n46. ↩︎