James Jackson Jarves (1818–1888), Florence, by 1859

The panel, of a vertical wood grain, retains its original thickness of 1.4 centimeters, but four vertical channels have been routed into the reverse to relieve some of the pressure of a convex warp, and two dovetail battens have been cut into the back, cross-grain, to maintain the planarity of the support. Traces of an original gesso coating and possibly some black(?) pigment survive beneath a thick layer of wax impregnating the entire back, routed channels, and battens. The original engaged frame moldings have been cut away on all four sides, but a continuous barb along the painted and gilt border indicates that none of the image has been lost. A major split running the full height of the panel 10 centimeters from the left edge passes through the face of Christ, and a shorter split 2 centimeters from the right edge has resulted in a loss of gesso and gilding at the top edge. Further small losses have occurred on the left edge at the top, on the right edge at the bottom, and along the bottom edge at the left of center. An old drilled hole in the bottom-right corner corresponds to a similar partial hole in the bottom-left corner of the companion Virgin and Child Enthroned with Six Angels.

The paint surface was harshly cleaned by Andrew Petryn in 1967, revealing extensive losses in the silver armor of the crowd of soldiers at the right. These were lightly repaired in tratteggio during a treatment by Irma Passeri in 2008–9. Four angels flying around the arms of the Cross are largely missing, visible only as engraved outlines and small islands of blue paint in the bottom pair and red paint in the upper pair. The spear heads and a banner projecting from the crowd of soldiers onto the gold ground are now only visible as engraved outlines. The figure of Christ is much abraded, and His loincloth is mostly missing. Shell gold chrysogony on the robes of the centurion is well preserved.

The two panels of this diptych (see Master of Monte Oliveto, Virgin and Child Enthroned with Six Angels), now missing their original frames and the physical evidence of their attachment to each other, were originally catalogued by James Jackson Jarves as the work of Duccio, at a period when nearly all early Sienese paintings bore that attribution and none of the many followers of Duccio subsequently identified by scholars were as yet known.1 Giacomo De Nicola first isolated a small Maestà in the monastery of Monte Oliveto Maggiore and with it the Jarves diptych as works by a distinct artist influenced by Duccio—an artist baptized the “Master of Monteoliveto” by Cesare Brandi in 1933.2 All subsequent authors have embraced this designation except for Charles Seymour, Jr., who seems to have been unaware of it despite the painting’s long publication history.3 Lingering disagreement, to the extent that there is any, concerns only the chronology of this artist’s work and his place within the development of the Ducciesque school of painting in Siena. For many scholars, the Master of Monte Oliveto was a direct follower of Duccio, while for others he was instead a follower of one of Duccio’s pupils, specifically Segna di Bonaventura, and therefore reflects Ducciesque models only at second hand.

Opinions regarding the date of the Jarves diptych and of the work of the Master of Monte Oliveto in general tend to range within the first two decades of the fourteenth century. Amplifying an argument first advanced by Brandi, James Stubblebine contended that the left valve of the Jarves diptych recorded the design of a lost altarpiece (and that the right valve reflected one of the compositions within its predella) painted by Duccio in 1302 for the Cappella delle Nove in the Palazzo Pubblico, Siena, a presumably seminal work otherwise known only from mention of it in documents.4 As supposed copies of a painting dated 1302, Stubblebine argued that the Jarves diptych and the Master’s eponymous work at the monastery of Monte Oliveto Maggiore were probably that artist’s earliest efforts, painted very close in time to the lost original. This argument is based exclusively on a hypothetical iconographic relationship, not on style. While the Jarves diptych is undoubtedly the Monte Oliveto Master’s earliest surviving painting, it has no direct chronological relationship to the Monte Oliveto Maestà itself, which must have been painted considerably later. Only two works correctly attributed to this artist use engraved rather than punched decoration in the haloes and along the borders of the gold ground: the Jarves diptych and the wings of a triptych in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (fig. 1), and both of these were manifestly painted later than Duccio’s Maestà for the high altar of the cathedral of Siena (1308–11).5 All of the Master’s other works employ more or less elaborate sequences of motif punches to decorate the gold grounds and are thus likely to date no earlier than ca. 1320.6 Given their uniformly small scale and apparently provincial distribution, a great number of these, perhaps a majority, may have been painted as late as the 1330s.

The Jarves diptych was included in the 1972 exhibition of “restored” paintings at Yale, the Crucifixion panel having been cleaned in 1967, the Virgin and Child Enthroned left for comparison in the state in which it had been found following its previous treatment in 1915. Charles Seymour, Jr., wrote in the exhibition catalogue only that “the cleaned panel [i.e., the Crucifixion] reveals the original blues which had been obscured to black and the subtle play of textures in contrasting pigments.”7 The Virgin and Child Enthroned was not commented upon in the exhibition catalogue. It reveals a complex structure that includes, in addition to discolored varnishes, unexpected strata of old repaints atypical of commercial reconstructions of the nineteenth century. Immediately apparent is the coarse, opaque texture of the cloth of honor behind the throne and angels, which contrasts clumsily with the translucent rose tones and elegant mordant gilding of the cloth covering the back and seat of the Virgin’s throne. The latter is entirely consonant in pattern, and in the density and palette of its rendering, with fabric types included in a wide range of Ducciesque paintings, whereas the former is not. The confronted parrots or falcons decorating this upper fabric and the opacity of its colors are commonly encountered not in Sienese but in Florentine panels, and not of the first but of the second half of the fourteenth century.8

To integrate this upper painted canopy with the rest of the composition, the artist responsible found it necessary to introduce several other adjustments. The top two angels on both sides of the Virgin’s throne wear robes of the same dense, flat orange color that occurs in this fabric, whereas the lowest angel on each side is clad in robes of translucent rose with mordant gilt decoration. The orange tunics of the two angels at the upper left are painted over remnants of mordant gilding, and it is reasonable to conclude that they, too, were “restored” early in the panel’s history. X-radiographs (fig. 2) reveal not only the broad, coarse brushwork by which these fabrics are constructed but also that they were painted around the hands of the angels, whereas the hands of the foreground angels are painted after—that is, on top of—their draperies. The same broad, coarse brushwork appears to reinforce all the white surfaces of the Virgin’s throne. The Gothic spires that rise from the top corners of the throne, painted on top of the second cloth canopy, are clearly later additions: no comparable architectural forms are to be found in any other Ducciesque paintings, although they are frequently encountered in mid- and late fourteenth-century Florentine panels. The strong black outlines that reinforce all the forms in this painting are undoubtedly also later additions, as are the darkened oil glazes on the lining of the cloth of honor, the ends of the Virgin’s cushions, and the inlays on her throne that achieve a chiaroscuro effect typically exploited by Florentine rather than Sienese artists. Finally, evidence of an original layer of gold visible through pinpoint flaking losses in the upper cloth canopy suggest that the gold ground presently visible at the top of the panel is actually a second layer of gold laid atop the first.

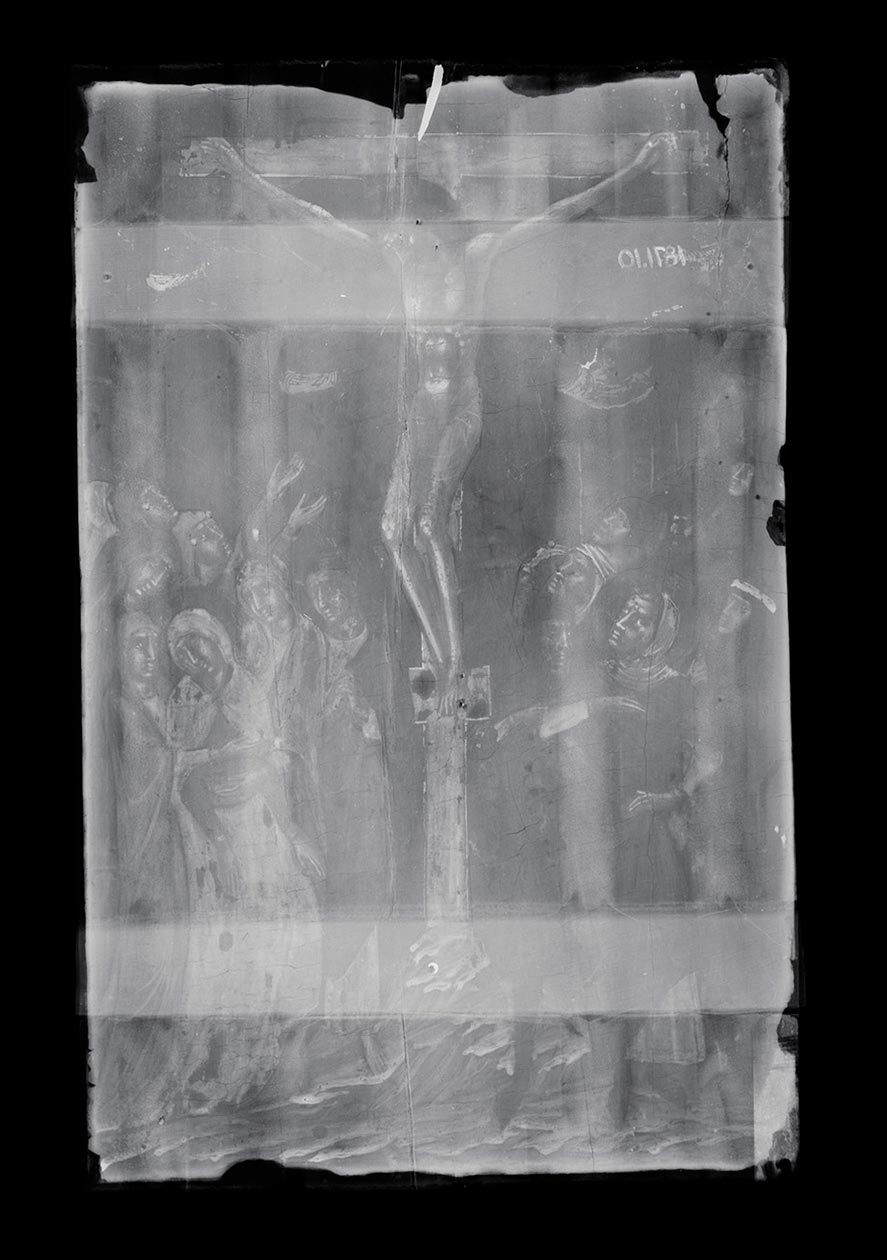

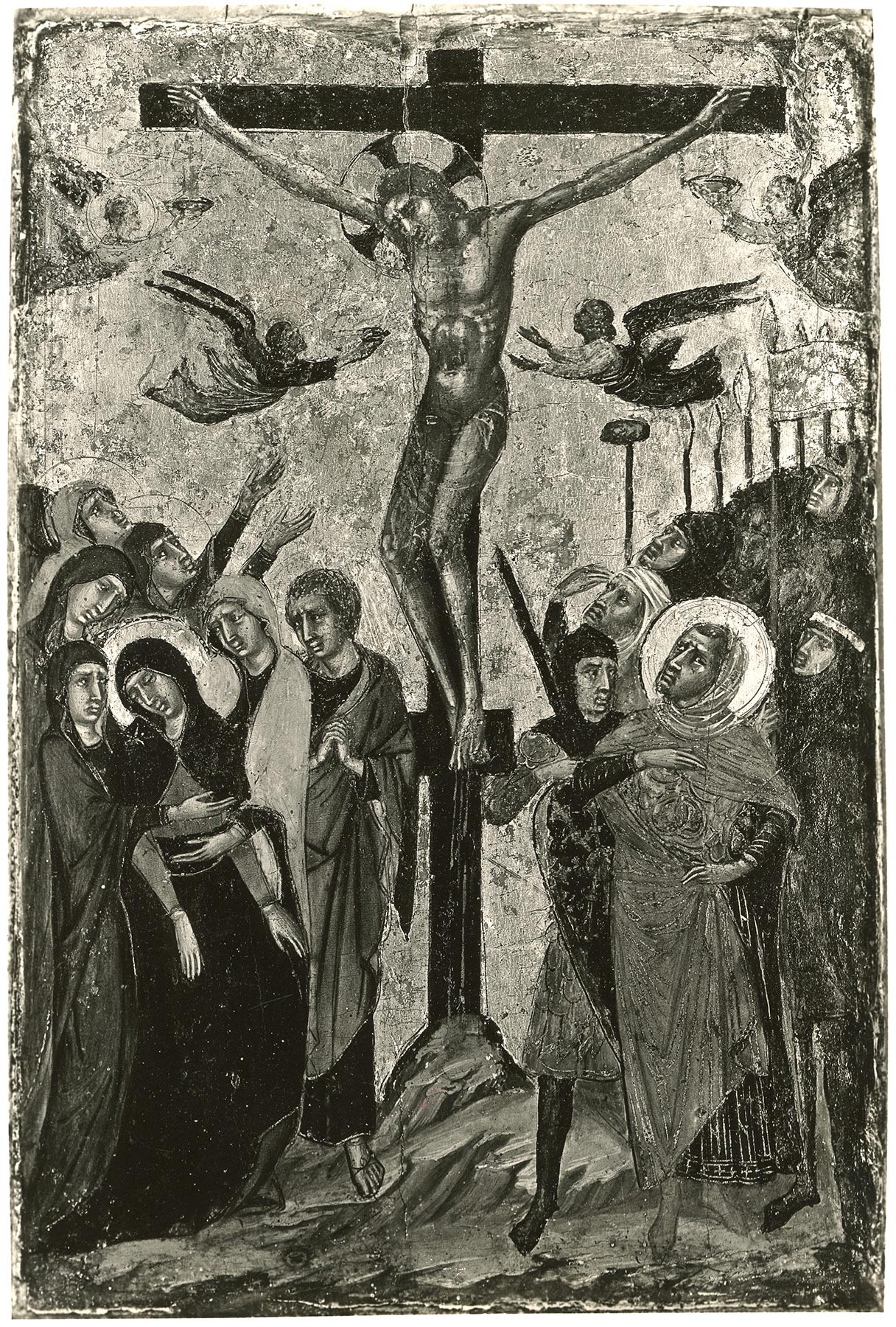

While it may be presumed that these revisions to the original composition of the Virgin and Child Enthroned panel were made less than a century and perhaps only half a century after it was first painted, there is no immediately apparent reason why they might have been required, unless it may have been related to warpage of the panel causing losses around its engaged frame. If the alterations were meant to compensate for damages suffered by the panel, they have completely masked any physical scars they may have been intended to cover. It is possible that they were simply meant to update the panel to a fashionably later and more locally Florentine taste, a procedure encountered with some frequency in the fifteenth century that may have been more widely diffused in the fourteenth century than the paucity of surviving examples would seem to imply.9 Few certain indications of later intervention survive on the Crucifixion panel after its thorough 1967 cleaning. The thick white highlights applied to the edges of the rocks at the foot of the Cross may be so interpreted: X-radiography (fig. 3) shows that these highlights were painted around the feet of Saint John the Evangelist and over his toes, suggestive but not unequivocal evidence that they are part of the second and not the first campaign of work on the diptych. Pre-1967 photographs of the Crucifixion (fig. 4) show the spearheads outlined in black and dark, oil-glazed shadows on the greaves of the soldiers’ armor and in the wings and draperies of the angels—all missing today—which may not have been later restorations in the conventional sense but instead fourteenth-century additions to the original composition in keeping with the alterations found in the companion panel. The coarsely ground blue pigment covering the Cross, which inexplicably fills only the arms and lower portion but not the top of the Cross, may also be later, as may be the blue surface of the Virgin’s cloak, the poorly defined area of black(?) at her waist—seemingly a broad sash, but no such article of clothing is known in any other Ducciesque painting—and the indistinct areas of color filling the spaces between the braced legs of two of the soldiers in the foreground. —LK

Published References

Jarves, James Jackson. Descriptive Catalogue of “Old Masters” Collected by James J. Jarves to Illustrate the History of Painting from A.D. 1200 to the Best Periods of Italian Art. Cambridge, Mass.: H. O. Houghton, 1860., 44, no. 21; Sturgis, Russell, Jr. Manual of the Jarves Collection of Early Italian Pictures. New Haven: Yale College, 1868., 27–28; W. F. Brown, Boston. Catalogue of the Jarves Collection of Early Italian Pictures. Sale cat. November 9, 1871., 13, no. 14; Rankin, William. “Some Early Italian Pictures in the Jarves Collection of the Yale School of Fine Arts at New Haven.” American Journal of Archaeology 10, no. 2 (April–June 1895): 137–51., 139–40; Perkins, F. Mason. “Pitture senesi negli Stati Uniti.” Rassegna d’arte senese 1 (1905): 74–78., 76; Rankin, William. Notes on the Collections of Old Masters at Yale University, the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, the Fogg Museum of Harvard University. Wellesley, Mass.: Department of Art, Wellesley College, 1905., 8, no. 14; De Nicola, Giacomo. “Duccio di Buoninsegna and His School in the Mostra di Duccio at Siena.” Burlington Magazine 22, no. 117 (December 1912): 138–39, 142–43, 145–47., 147; Sirén, Osvald. A Descriptive Catalogue of the Pictures in the Jarves Collection Belonging to Yale University. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1916., 31–33, no. 10; Offner, Richard. Italian Primitives at Yale University: Comments and Revisions. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1927., 4, 38, fig. 27; Venturi, Lionello. Pitture italiane in America. 2 vols. Milan: Ulrico Hoepli, 1931., pls. 19–20; Berenson, Bernard. Italian Pictures of the Renaissance: A List of the Principal Artists and Their Works with an Index of Places. Oxford: Clarendon, 1932., 524; Brandi, Cesare. La Regia Pinacoteca di Siena. Rome: La Libreria dello Stato, 1933., 176; Brandi, Cesare. Duccio. Florence: Vallecchi, 1951., 141n23; Coor, Gertrude. “A New Attribution to the Monte Oliveto Master and Some Observations Concerning the Chronology of His Work.” Burlington Magazine 97, no. 628 (July 1955): 203–7., 203, 207; Klesse, Brigitte. Seidenstoffe in der italienischen Malerei des 14. Jahrhunderts. Bern, Switzerland: Stämpfli, 1967., 328; Berenson, Bernard. Italian Pictures of the Renaissance, A List of the Principal Artists and Their Works with an Index of Places: Central Italian and North Italian Schools. 3 vols. London: Phaidon, 1968., 1:83; Seymour, Charles, Jr. Early Italian Paintings in the Yale University Art Gallery. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1970., 71, 73, 310, nos. 49a–b; Fredericksen, Burton B., and Federico Zeri. Census of Pre-Nineteenth-Century Italian Paintings in North American Public Collections. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1972., 599; Charles Seymour, Jr., in Seymour, Charles, Jr., et al. Italian Primitives: The Case History of a Collection and Its Conservation. Exh. cat. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1972., 43, no. 34; Stubblebine, James. “Duccio’s Maestà of 1302 for the Chapel of the Nove.” Art Quarterly 35 (1972): 239–68., 240, 243, 245, 251, 260–61; Vertova, Luisa. “The New Yale Catalogue.” Burlington Magazine 115 (March 1973): 159–61, 163., 159–60; Zeri, Federico. Italian Paintings in the Walters Art Gallery. 2 vols. Baltimore: Walters Art Gallery, 1976., 1:36; Stubblebine, James. Duccio di Buoninsegna and His School. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1979., 1:94–95; Pope-Hennessy, John, and Laurence Kanter. The Robert Lehman Collection. Vol. 1, Italian Paintings. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1987., 2, 4; Garland, Patricia Sherwin. “Recent Solutions to Problems Presented by the Yale Collection.” In Early Italian Paintings: Approaches to Conservation; Proceedings of a Symposium at the Yale University Art Gallery, April 2002, ed. Patricia Sherwin Garland, 54–70. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 2003., 58, 61, figs. 3.3–.4; Kanter, Laurence. “Some Early Sienese Paintings: Cleaned, Uncleaned, Restored, Unrestored; What Have We Learned?” Yale University Art Gallery Bulletin (2010): 46–65., 59–65

Notes

-

Jarves, James Jackson. Descriptive Catalogue of “Old Masters” Collected by James J. Jarves to Illustrate the History of Painting from A.D. 1200 to the Best Periods of Italian Art. Cambridge, Mass.: H. O. Houghton, 1860., 44, no. 21. ↩︎

-

De Nicola, Giacomo. “Duccio di Buoninsegna and His School in the Mostra di Duccio at Siena.” Burlington Magazine 22, no. 117 (December 1912): 138–39, 142–43, 145–47., 147; and Brandi, Cesare. La Regia Pinacoteca di Siena. Rome: La Libreria dello Stato, 1933., 176. ↩︎

-

Seymour, Charles, Jr. Early Italian Paintings in the Yale University Art Gallery. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1970., 71, 73, 310, nos. 49a–b; and Charles Seymour, Jr., in Seymour, Charles, Jr., et al. Italian Primitives: The Case History of a Collection and Its Conservation. Exh. cat. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1972., 43, no. 34. ↩︎

-

Brandi, Cesare. Duccio. Florence: Vallecchi, 1951., 141n23; and Stubblebine, James. Duccio di Buoninsegna and His School. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1979., 94–95. ↩︎

-

Stubblebine, James. Duccio di Buoninsegna and His School. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1979., 1:100, recognized the derivation of several scenes on the panels in figure 1 from prototypes on Duccio’s cathedral Maestà of 1308–11 but did not acknowledge this as a terminus post quem for the Master of Monte Oliveto’s early career. He furthermore assumed the wings were integral to the center panel (Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, inv. no. 41.190.31a, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/440985)—which he attributed to a suppositious Tabernacle 39 Master but which can now be identified as the work of Ugolino di Nerio—and therefore that, in this collaboration, it was the influence of the second artist on the Master of Monte Oliveto that accounted for the “softening” of the style of the latter. The wings and center panel of the Metropolitan triptych were actually assembled in comparatively modern times. ↩︎

-

The introduction of motif punches as a regular practice in Sienese trecento painting is usually credited to Simone Martini around the years 1315–20. Such punches were used with irregular frequency in the thirteenth century, but after 1320 they came to be the norm for panel painting decoration in that city. They do not appear in Florentine painting until ca. 1333. See Skaug 2013. ↩︎

-

Charles Seymour, Jr., in Seymour, Charles, Jr., et al. Italian Primitives: The Case History of a Collection and Its Conservation. Exh. cat. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1972., 43. ↩︎

-

Klesse, Brigitte. Seidenstoffe in der italienischen Malerei des 14. Jahrhunderts. Bern, Switzerland: Stämpfli, 1967., 328, lists the Yale panel as a parallel example for her pattern no. 262, by Niccolò di Segna. A closer match, however, is to be found with her patterns no. 259, from a Florentine work dated 1372, or nos. 267 and 269, from paintings by the Master of Santa Verdiana (Tommaso del Mazza) in the last quarter of the fourteenth century. ↩︎

-

One particularly relevant example is the Virgin and Child in the Robert Lehman Collection at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, inv. no. 1975.1.10, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/459134, catalogued by John Pope-Hennessy, in Pope-Hennessy, John, and Laurence Kanter. The Robert Lehman Collection. Vol. 1, Italian Paintings. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1987., 24, no. 10, as by the Sienese painter Naddo Ceccarelli, modernized by a late fourteenth-century Florentine artist. The original passages in this painting are actually by Barna da Siena/Lippo Memmi, not Ceccarelli, but the circumstances of the panel’s alterations nevertheless closely parallel those inferred here for the Jarves diptych by the Master of Monte Oliveto. ↩︎