James Jackson Jarves (1818–1888), Florence, by 1859

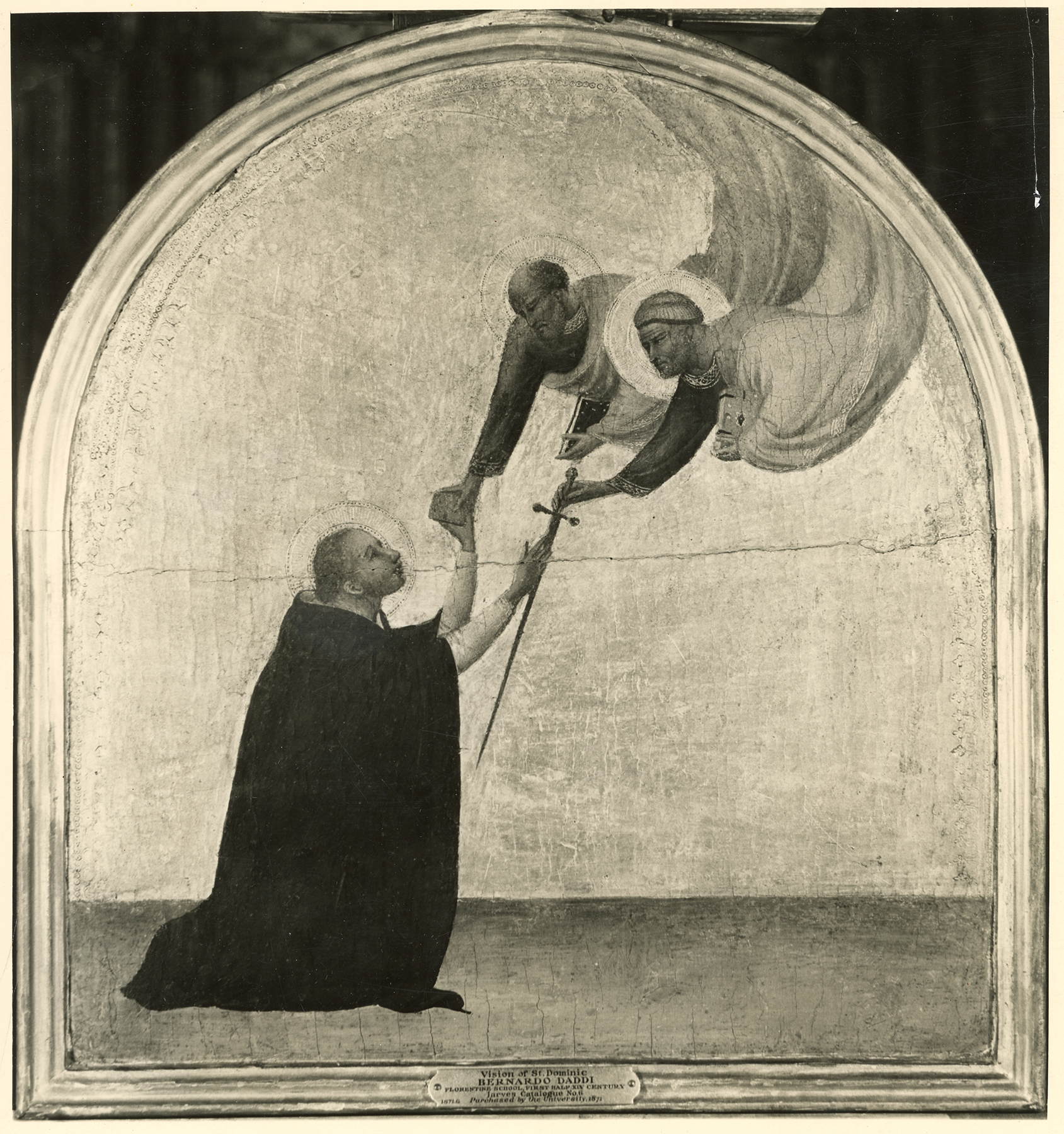

The panel support, of a horizontal grain, has been thinned to a depth varying between 7 and 10 millimeters and exhibits a pronounced convex warp. A split running the full width of the panel on a slight diagonal rises from the bottom of the spring of the arch at left to the top of the spring of the arch at right, resulting in a near-complete loss of pigment where it crosses through the head of Saint Dominic. In 1915 Hammond Smith noted that this head had suffered flaking losses, but these were revealed in photographs to have been minor (fig. 1). He recradled the panel at that time and repainted the head of Saint Dominic (fig. 2). His restorations and cradle were removed by Andrew Petryn in 1957, and the split was glued together. In this cleaning, the gold ground was abraded to its bolus and gesso underlayers, the head of Saint Dominic was obliterated, and the beards of Saints Peter and Paul were removed. The two latter figures are otherwise reasonably well preserved, except for the trailing end of Saint Peter’s pink robe, as are the black and white of Saint Dominic’s habit, including his left cuff and right hand where they pass over the split in the panel. Also removed in the 1957 cleaning was the sword that had been painted over a staff proffered by Saint Paul to Saint Dominic. Only the engraved profile of the staff remains today. The hands of all three saints retain much of their expressive character.

Associated by James Jackson Jarves and by early commentators on his collection with the name of Giotto’s foremost pupil, Taddeo Gaddi, the Vision of Saint Dominic was first recognized by Osvald Sirén as the work of Bernardo Daddi, part of the earliest reconstructions of that artist’s personality.1 This attribution has not been doubted or questioned since, and the painting has indeed come to be accepted—as its lengthy bibliography attests—as one of the iconic images of early trecento painting in Florence. Roberto Longhi, who held Daddi in far lower esteem than did any of his non-Italian contemporaries, went so far as to label it the apogee of Daddi’s career (“[L’artista] non era mai salito più in alto [in qualità]”).2 The only debate the panel has elicited has revolved around its iconography, its condition, and the identification of the complex from which it came.

According to the Golden Legend, around the time that Saint Dominic petitioned Pope Innocent III for approval for his Order of Preachers (ultimately granted by Pope Honorius III in 1216), “while he was praying in the church of Saint Peter for the expansion of his Order, Peter and Paul, the glorious princes of the apostles, appeared to him. Peter gave him a staff, and Paul a book, and they said: ‘Go forth and preach, for God has chosen you for this ministry.’”3 In the Yale panel, Bernardo Daddi has eliminated all reference to the interior of Old Saint Peter’s in Rome, where Dominic was vouchsafed this vision, to convey more powerfully the substance of the miraculous apparition isolated against an uninterrupted gold ground in an indistinct space and imprecise time. In the state in which this panel was known to all scholars before 1957, however, Saint Peter handed a sword rather than a staff to Saint Dominic (see figs. 1–2). In the 1860 catalogue of his collection, Jarves admitted that “some authorities say it was a staff, not a sword, that was given. But Gaddi’s [sic] sword is more in keeping with the founder of the Inquisition.”4 For Russel Sturgis, Jr., and Sirén, the sword and the book were “the weapons by which [Dominic] was to conquer the world.”5 Raimond van Marle noted that “the Golden Legend really mentions a book and a stick,”6 and because of this, Richard Offner opined that “we must assume that through a misunderstanding the staff was altered into the sword by some restorer.”7 The accuracy of this contention was made evident when Charles Seymour, Jr., published a cleaned-state photograph of the painting in 1970, although he made no reference to the alteration in his brief catalogue entry and instead repeated, mistakenly, that the Golden Legend speaks of the gift of a sword as a symbol of the Dominicans’ role in suppressing heresy.8 Miklós Boskovits published before- and after-cleaning photographs of the panel as successive plates in his revised edition of Offner’s 1930 Corpus volume dedicated to Bernardo Daddi,9 and since then, not surprisingly, the painting has largely disappeared from general discussions of the art of Florence in the trecento.

Before the Yale Vision of Saint Dominic was firmly associated with Bernardo Daddi, Bernard Berenson recognized a companion panel to it in a scene of Saint Dominic rescuing a ship at sea formerly in the Raczynski collection in Berlin, now in the Muzeum Narodowe in Poznań (fig. 3).10 Unaware of the connection between these two panels, Sirén called attention to a painting in the Musée des Arts Décoratifs, Paris, showing Saint Peter Martyr preaching (fig. 4), that, he believed, must also have formed, with the Yale panel, “part of a predella under a picture with the two above-mentioned Dominican saints (St. Dominic and St. Peter Martyr) probably together with one or more other saints.”11 Sirén further proposed that, “although we cannot yet know how the whole picture was composed (because the principal parts are lacking), it does not seem too daring to make the supposition that it was identical with a picture which, according to a notice in the ‘Sepoltuario del Rosselli,’ Vol. ii, p. 739, once hung in Sta. Maria Novella in Florence, and bore the following inscription: ‘Pro animabus parentum fratris Guidonis Salvi et pro anima domine Diane de Casinis Anno MCCCXXXVIII. Bernardus me pinxit’” (For the souls of the family of fra Guido Salvi and for the soul of Lady Diana Casini, Bernardo painted me in the year 1338).12 This tentative proposal has been accepted, prima facie, by all subsequent writers. The appearance of a fourth panel from the same predella, now in the Gemäldegalerie, Staatlichen Museen zu Berlin, and showing Saint Thomas Aquinas rewarded for resisting temptation (fig. 5), tended to confirm this assumption since the painting described in the Sepoltuario is said to have been “una tavola antichissima entroci tre Santi dell’Ordine di S. Domenico,” thus, supposedly, Saints Dominic, Peter Martyr, and Thomas Aquinas.13

While the association of the four panels now at Yale, Poznań, Paris, and Berlin with a single predella is incontestable, their connection to the Salvi altarpiece of 1338 in Santa Maria Novella is in fact only a plausible hypothesis, notwithstanding its uncritical repetition and acceptance as established fact in every publication following Sirén’s initial proposal. It can scarcely be doubted that the altarpiece to which this predella was once attached was painted for an important Dominican church and, given the originality of the iconography in each of the four scenes, it is not unreasonable to assume that this church was Santa Maria Novella. However, Daddi painted at least two, probably three, but perhaps as many as five altarpieces for Santa Maria Novella, and there is no certainty which, if any of these, might have been that described by Rosselli for Fra Guido Salvi and Diana Casini. A polyptych depicting the Virgin and Child Enthroned with Saints Peter, John the Evangelist, John the Baptist, and Matthew, signed by the artist and dated 1344 (and therefore unlikely to be the Salvi/Casini polyptych), now stands on the altar in the Spanish Chapel in Santa Maria Novella.14 A large altarpiece of the Coronation of the Virgin that includes effigies of the three principal Dominican saints among the court of Heaven was removed from Santa Maria Novella in 1810 and is now in the Galleria dell’Accademia, Florence (fig. 6).15

The only known independent representation of Saint Dominic by Bernardo Daddi, a panel formerly in the Charles Loeser collection (fig. 7), was reconstructed by Offner as one lateral of an altarpiece that included at its center the Virgin and Child in the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston.16 Neither panel has a known early provenance, but it is certainly conceivable that they came from Santa Maria Novella. Boskovits reconstructed another polyptych by Bernardo Daddi—which includes figures of Saints Peter, John the Evangelist, John the Baptist, and Zenobius—with a hypothetical provenance from a chapel owned by the Minerbetti family in Santa Maria Novella.17 If the altarpiece described by Rosselli was not one of these four, it is at least theoretically possible that a fifth altarpiece by Daddi was painted for that church.

It was assumed by Sirén, in making his initial proposal, that the Salvi altarpiece was a conventional Gothic polyptych that included three Dominican saints among its lateral panels, an assumption that provided a suitable basis for amalgamating to it the two predella panels known to him. The ex-Loeser Saint Dominic (see fig. 7) could lend itself to such a reconstruction, though it is slightly wider than might be expected if one of the predella panels were to have fit neatly beneath it.18 Offner, in his reconstruction of the Salvi altarpiece, projected a triptych containing only the three Dominican saints—Dominic at center flanked by Peter Martyr and Thomas Aquinas—proceeding from the assumption that two scenes from the legend of Saint Dominic presupposed a center panel portraying that saint twice as wide as the lateral panels portraying the other two, which would each have surmounted only a single scene.19 For Boskovits, Rosselli’s wording in the Sepoltuario could only be reconciled with a single, unified panel, and the vertical, arched shape of the predella scenes seemed to him appropriate to such a structure.20 Returning to and embellishing Sirén’s proposal, Carl Strehlke has pointed out that the individual scenes by Daddi in the predella to the San Pancrazio altarpiece, now in the Gallerie degli Uffizi, Florence,21 are close to the present panels in size and format, yet that altarpiece is a conventional polyptych. He has suggested that two scenes now missing, plausibly drawn from the life of Christ or the Virgin, may have stood beneath a central Virgin and Child while the four known predella panels could then have been distributed beneath lateral panels portraying Saints Peter Martyr (Paris), Dominic (Poznań), Peter or Paul (Yale), and Thomas Aquinas (Berlin).22

The most widely accepted of these proposals seem to be the strict interpretations of Rosselli advanced by Offner and Boskovits: that no figures other than the three Dominican saints were portrayed in the Salvi altarpiece, whether it was a single panel or a triptych. Offner’s reconstruction of a triptych is definitively to be rejected, however, by the recent discovery of a fifth panel from the predella showing the Miraculous Healing of Napoleone Orsini by Saint Dominic (fig. 8).23 Three scenes from the legend of Saint Dominic clustered beneath a center panel would create an unprecedented differential of proportion to lateral panels each standing above a single predella scene with Saints Thomas Aquinas and Peter Martyr. It is equally difficult to envision the reconstruction of a single, continuous panel as proposed by Boskovits, given the complete absence of any later works of art replicating this exceptional format: the altarpiece would have represented a distinguished and significant early example of Dominican “portraiture” in the most prominent of all Dominican centers in Florence and should be expected to have engendered respectful imitations. Furthermore, the existence of additional scenes not yet recovered may be implied not only by the recent appearance of the Miraculous Healing of Napoleone Orsini but also by the unusual selection of episodes now known from the lives of each of the saints. Only the Vision of Saint Dominic and Miracle of Napoleone Orsini would become standard iconography in pictorial cycles of that saint’s life, and when they appear in such cycles, it is invariably among the earliest events in a more extensive narrative of his legend. Two distinct possibilities for identifying the Salvi altarpiece, therefore, remain. Either it took the form of a conventional polyptych that included the Yale predella panel and its companion scenes, whether or not it or some fragment of it may be identifiable among the surviving large-scale works of Bernardo Daddi, or the Salvi altarpiece did not include the Yale and related predella panels and there survives no other physical evidence for reconstructing its form.

In the case of the first of these possibilities, there are only two candidates that might be identifiable as remnants of the Salvi altarpiece: the Coronation of the Virgin (see fig. 6) now in the Accademia in Florence and the ex-Loeser Saint Dominic (see fig. 7), both of which have either a known or plausible provenance from Santa Maria Novella. As has been noted, the Accademia Coronation contains images of the three Dominican saints, conforming to Rosselli’s description of the Salvi altarpiece, and it is large enough (188.6 × 270 cm) to have accommodated the five known predella panels, the missing columns and framing arches that once separated them, and up to two hypothetical further scenes. It is, however, almost certainly datable between 1343 and 1345 and therefore could be identical with the Salvi altarpiece only if Rosselli misread the date in the inscription, mistaking an X (MCCCXXXXIII) for a V (MCCCXXXVIII).24 While this is possible, it is unreasonable to advance as a working hypothesis without further evidence pointing in that direction. The ex-Loeser Saint Dominic has also been dated by Erling Skaug close to 1342 on sphragiological grounds,25 but there is no objective standard available to demonstrate this argument as there are no surviving, firmly dated works by Daddi between 1338 and 1343. Skaug argued conclusively for a terminus post quem of 1338 for the ex-Loeser panel, but finer judgments beyond that must be acknowledged as tentative. Yet, while it is at least logically possible that the ex-Loeser Saint Dominic was part of the Salvi altarpiece, no physical evidence positively links it to the predella, and so no association of the latter with the date 1338 can be claimed to be more than a circumstantial possibility. Further delimiting the likely date of the predella on stylistic grounds has not been possible, given the abraded state of all the known panels. They are conventionally assumed to be datable to 1338 based on the belief that they were part of the Salvi altarpiece, but that is a supposition that cannot be conclusively demonstrated.

One final problematic consideration relating to Rosselli’s description of the Salvi altarpiece deserves further inquiry. Rosselli records the altarpiece as hanging on the west wall of a cloister at Santa Maria Novella but claims to have been informed by the friars that it was originally installed in the choir of the church (“Dicono i Frati che era in Chiesa intorno al coro . . . che ne fu levato intorno all’anno 1570”).26 If the painting hung on the rood screen in Santa Maria Novella and bore a date and Bernardo Daddi’s signature, it begs the question of Vasari’s omitting to mention it and of his mistaken belief that Bernardo da Firenze was a follower of Spinello Aretino at the end of the fourteenth century.27 If, on the other hand, the altarpiece had already been removed from the rood screen before the date of Vasari’s reconstruction of the altars in the church, it may not be idle speculation to wonder whether the “storiette piccole” mentioned by Vasari in the chapel of the Coronation of the Virgin on the rood screen in Santa Maria Novella, attributed by him to Fra Angelico, might instead be the five Dominican scenes by Bernardo Daddi, separated from their original context due to their enduring iconographic value to the community.28 While impossible to verify, such a hypothesis could also explain the survival of the predella scenes independent of the altarpiece to which they were originally attached. —LK

Published References

Jarves, James Jackson. Descriptive Catalogue of “Old Masters” Collected by James J. Jarves to Illustrate the History of Painting from A.D. 1200 to the Best Periods of Italian Art. Cambridge, Mass.: H. O. Houghton, 1860., 44; Jarves, James Jackson. Art Studies: The “Old Masters” of Italy; Painting. New York: Derby and Jackson, 1861., pl. C, fig. 11; Sturgis, Russell, Jr. Manual of the Jarves Collection of Early Italian Pictures. New Haven: Yale College, 1868., 34; Rankin, William. “Some Early Italian Pictures in the Jarves Collection of the Yale School of Fine Arts at New Haven.” American Journal of Archaeology 10, no. 2 (April–June 1895): 137–51., 141; Rankin, William. Notes on the Collections of Old Masters at Yale University, the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, the Fogg Museum of Harvard University. Wellesley, Mass.: Department of Art, Wellesley College, 1905., 8; Sirén, Osvald. “Trecento Pictures in American Collections—II.” Burlington Magazine 14, no. 69 (December 1908): 188–94., 188–89, 193, pl. 1, fig. 1; Van Vechten Brown, Alice, and William Rankin. A Short History of Italian Painting. London: J. M. Dent, 1914., 65n3; Sirén, Osvald. A Descriptive Catalogue of the Pictures in the Jarves Collection Belonging to Yale University. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1916., 21–23, no. 6; Sirén, Osvald. “Italian Pictures of the Fourteenth Century in the Jarves Collection.” Art in America 4, no. 4 (June 1916): 207–23., 208–9; Sirén, Osvald. Giotto and Some of His Followers. Trans. Frederic Schenck. 2 vols. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1917., 1:180, 271; 2: pl. 161; van Marle, Raimond. The Development of the Italian Schools of Painting. Vol. 3. The Hague: M. Nijhoff, 1924., 370, 373–75; Offner, Richard. Italian Primitives at Yale University: Comments and Revisions. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1927., 3, 16, fig. 6; Comstock, Helen. “The Bernardo Daddis in the United States—Part II.” International Studio 89, no. 370 (March 1928): 71–76, 90., 71–73; Salmi, Mario. Review of Italian Primitives at Yale University: Comments and Revisions, by Richard Offner. Rivista d’arte 11 (1929): 267–73., 268; Borenius, Tancred. “Pictures from American Collections at Burlington House.” Apollo 11 (March 1930): 154., 154; Offner, Richard. A Critical and Historical Corpus of Florentine Painting: The Fourteenth Century. Sec. 3, vol. 3, The Works of Bernardo Daddi. New York: Institute of Fine Arts, New York University, 1930., 9, 36–39; Royal Academy of Arts. Exhibition of Italian Art, 1200–1900. Exh. cat. London: The Academy, 1930., 38–39; Lord Balniel and Kenneth Clark. A Commemorative Catalogue of the Exhibition of Italian Art Held in the Galleries of the Royal Academy, Burlington House, London, January–March 1930. Exh. cat. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1931., 13; Hautecoeur, Louis. Les primitifs italiens. Paris: Henri Laurens, 1931., 157; Venturi, Lionello. Pitture italiane in America. 2 vols. Milan: Ulrico Hoepli, 1931., pl. 36; Berenson, Bernard. Italian Pictures of the Renaissance: A List of the Principal Artists and Their Works with an Index of Places. Oxford: Clarendon, 1932., 167; Catalogue of “A Century of Progress”: Exhibition of Paintings and Sculpture Lent from American Collections. Exh. cat. Chicago: Art Institute of Chicago, 1933., 14, no. 84; Venturi, Lionello. Italian Paintings in America. Trans. Countess Vanden Heuvel and Charles Marriott. 3 vols. New York: E. Weyhe, 1933., pl. 45; Mostra giottesca. Exh. cat. Bergamo: Instituto Italiano d’Arti Grafiche, 1937., 56, no. 60; Arts of the Middle Ages: A Loan Exhibition. Exh. cat. Boston: Museum of Fine Arts, 1940., 19–20, no. 55; Cibulka, Josef. “Bernardo Daddi a jeho dva Triptychy v Národní Galerii v Praha.” Umení 13 (1940–41): 347–62., 352–54 ; Sinibaldi, Giulia, and Giulia Brunetti, eds. Pittura italiana del duecento e trecento: Catalogo della mostra giottesca di Firenze del 1937. Exh. cat. Florence: Sansoni, 1943., 501; Comstock, Helen. “The Yale Collection of Italian Paintings.” Connoisseur 118 (September 1946): 45–52., 46, 47; Offner, Richard. A Critical and Historical Corpus of Florentine Painting: The Fourteenth Century. Sec. 3, vol. 5, Master of San Martino alla Palma; Assistant of Daddi; Master of the Fabriano Altarpiece. New York: Institute of Fine Arts, New York University, 1947., 59, 65, 66n3, 67n9; Antal, Frederick. Florentine Painting and Its Social Background. London: Kegan Paul, 1948., 183; Gronau, Hans D. “The Literature of Art: A New Volume of Offner’s Corpus of Florentine Painting.” Review of A Critical and Historical Corpus of Florentine Painting: The Fourteenth Century, sec. 3, vol. 5, by Richard Offner. Burlington Magazine 91, no. 559 (October 1949): 294–95., 295; Paatz, Walter, and Elizabeth Paatz. Die Kirchen von Florenz. 6 vols. Frankfurt am Main: Klostermann, 1940–54., 748, 838nn490–91; Bialostocki, Jan, and Michal Walicki. Malarstwo europejskie w zbiorach polskich, 1300–1800. Kraków, Poland: PIW, 1955., 455; Offner, Richard. A Critical and Historical Corpus of Florentine Painting: The Fourteenth Century. Sec. 3, vol. 8, Workshop of Bernardo Daddi. New York: Institute of Fine Arts, New York University, 1958., 4, 202; Longhi, Roberto. “Qualità e industria in Taddeo Gaddi ed altri—II.” Paragone 10, no. 111 (March 1959): 3–12., 7–8; Kalinowski, Konstanty. La peinture italienne des XIVe et XVe siècles: Musée National de Cracovie. Kraków, Poland: Musée National de Cracovie, 1961., 42; Berenson, Bernard. Italian Pictures of the Renaissance, A List of the Principal Artists and Their Works with an Index of Places: The Florentine School. 2 vols. London: Phaidon, 1963., 1:56, 2: fig. 172; Marcucci, Luisa. Gallerie nazionali di Firenze: I dipinti toscani del secolo XIV. Cataloghi dei musei e gallerie d’Italia. Rome: Istituto Poligrafico dello Stato, 1965., 36; White, John. Art and Architecture in Italy, 1250 to 1400. Baltimore: Penguin, 1966., 264; Dal Poggetto, Paolo. Omaggio a Giotto. Florence: S.T.I.A.V., 1967., 33; Seymour, Charles, Jr. Early Italian Paintings in the Yale University Art Gallery. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1970., 24–27, no. 9; Fredericksen, Burton B., and Federico Zeri. Census of Pre-Nineteenth-Century Italian Paintings in North American Public Collections. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1972., 62, 599; Preiser, Arno. Das Entstehen und die Entwicklung der Predella in der italienischen Malerei. Hildesheim, Germany: Georg Olms, 1973., 324–25; Gardner, Julian. “Andrea di Bonaiuto and the Chapterhouse Frescoes in Santa Maria Novella.” Art History 2, no. 2 (1979): 107–38., 114; Boskovits, Miklós. Frühe italienische Malerei: Gemäldegalerie Berlin, Katalog der Gemälde. Berlin: Mann, 1988., 27–28, 254; Offner, Richard. A Critical and Historical Corpus of Florentine Painting: The Fourteenth Century. Sec. 3, vol. 3, The Works of Bernardo Daddi. Ed. Miklós Boskovits. Florence: Giunti, 1989., 71, 188, 196–200, 385; Pope-Hennessy, John. Learning to Look. New York: Doubleday, 1991., 302–3; Skaug, Erling S. Punch Marks from Giotto to Fra Angelico: Attribution, Chronology, and Workshop Relationships in Tuscan Panel Painting, with Particular Consideration to Florence, c. 1330–1430. 2 vols. Oslo: International Institute for Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works—Nordic Group, 1994., 1:101; Tartuferi, Angelo. Bernardo Daddi: L’incoronazione di Santa Maria Novella. Livorno: Sillabe, 2000., 53; Offner, Richard. A Critical and Historical Corpus of Florentine Painting: The Fourteenth Century. Sec. 3, vol. 5, Bernardo Daddi and His Circle. Ed. Miklós Boskovits. Florence: Giunti, 2001., 173, 178; Cannon, Joanna. Religious Poverty, Visual Riches: Art in the Dominican Churches of Central Italy in the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2013., 326

Notes

-

Sirén, Osvald. “Trecento Pictures in American Collections—II.” Burlington Magazine 14, no. 69 (December 1908): 188–94., 188–89, 193, pl. 1, fig. 1. ↩︎

-

Longhi, Roberto. “Qualità e industria in Taddeo Gaddi ed altri—II.” Paragone 10, no. 111 (March 1959): 3–12., 7. ↩︎

-

de Voragine, Jacobus. The Golden Legend. Trans. William Granger Ryan. 2 vols. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1993., 2:47. ↩︎

-

Jarves, James Jackson. Descriptive Catalogue of “Old Masters” Collected by James J. Jarves to Illustrate the History of Painting from A.D. 1200 to the Best Periods of Italian Art. Cambridge, Mass.: H. O. Houghton, 1860., 44. ↩︎

-

Sturgis, Russell, Jr. Manual of the Jarves Collection of Early Italian Pictures. New Haven: Yale College, 1868., 34; and, for the quote, Sirén, Osvald. “Italian Pictures of the Fourteenth Century in the Jarves Collection.” Art in America 4, no. 4 (June 1916): 207–23., 208. ↩︎

-

van Marle, Raimond. The Development of the Italian Schools of Painting. Vol. 3. The Hague: M. Nijhoff, 1924., 370n3. ↩︎

-

Offner, Richard. A Critical and Historical Corpus of Florentine Painting: The Fourteenth Century. Sec. 3, vol. 5, Master of San Martino alla Palma; Assistant of Daddi; Master of the Fabriano Altarpiece. New York: Institute of Fine Arts, New York University, 1947., 59, 65, 66n3, 67n9. ↩︎

-

Seymour, Charles, Jr. Early Italian Paintings in the Yale University Art Gallery. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1970., 24–27, no. 9. ↩︎

-

Offner, Richard. A Critical and Historical Corpus of Florentine Painting: The Fourteenth Century. Sec. 3, vol. 3, The Works of Bernardo Daddi. Ed. Miklós Boskovits. Florence: Giunti, 1989., 197–98. ↩︎

-

Cited in Rankin, William. Notes on the Collections of Old Masters at Yale University, the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, the Fogg Museum of Harvard University. Wellesley, Mass.: Department of Art, Wellesley College, 1905., 8. ↩︎

-

Sirén, Osvald. “Trecento Pictures in American Collections—II.” Burlington Magazine 14, no. 69 (December 1908): 188–94., 193. ↩︎

-

Sirén, Osvald. “Trecento Pictures in American Collections—II.” Burlington Magazine 14, no. 69 (December 1908): 188–94., 193. The citation from the Sepoltuario Rosselli was first published by Gaetano Milanesi, in Vasari, Giorgio. Le vite de’ più eccellenti pittori, scultori ed architettori. With new annotations and comments by Gaetano Milanesi. 9 vols. Florence: G. C. Sansoni, 1878–85., 1:673n2. ↩︎

-

The Gemäldegalerie panel, thought to represent a miracle of Saint Dominic, was first associated with the others by van Marle, Raimond. The Development of the Italian Schools of Painting. Vol. 3. The Hague: M. Nijhoff, 1924., 373–75. The correct subject was identified by Richard Offner, cited in the 1931 catalogue of the Gemäldegalerie, and a full reconstruction of the predella was published by Offner in 1947; see Offner, Richard. A Critical and Historical Corpus of Florentine Painting: The Fourteenth Century. Sec. 3, vol. 3, The Works of Bernardo Daddi. Ed. Miklós Boskovits. Florence: Giunti, 1989., 185–205, pl. 8. ↩︎

-

Offner, Richard. A Critical and Historical Corpus of Florentine Painting: The Fourteenth Century. Sec. 3, vol. 5, Bernardo Daddi and His Circle. Ed. Miklós Boskovits. Florence: Giunti, 2001., 210–20, pl. 17. ↩︎

-

Offner, Richard. A Critical and Historical Corpus of Florentine Painting: The Fourteenth Century. Sec. 3, vol. 5, Bernardo Daddi and His Circle. Ed. Miklós Boskovits. Florence: Giunti, 2001., 255–72, pl. 22; and Paatz, Walter, and Elizabeth Paatz. Die Kirchen von Florenz. 6 vols. Frankfurt am Main: Klostermann, 1940–54., 745, 748, 836–37n467. ↩︎

-

Offner, Richard. A Critical and Historical Corpus of Florentine Painting: The Fourteenth Century. Sec. 3, vol. 5, Bernardo Daddi and His Circle. Ed. Miklós Boskovits. Florence: Giunti, 2001., 183–92, pls. 13–14. For the Virgin and Child, see Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston, inv. no. P15w26, https://www.gardnermuseum.org/experience/collection/10933. ↩︎

-

Offner, Richard. A Critical and Historical Corpus of Florentine Painting: The Fourteenth Century. Sec. 3, vol. 5, Bernardo Daddi and His Circle. Ed. Miklós Boskovits. Florence: Giunti, 2001., 237–54, 273–76, pls. 21, 23. ↩︎

-

The ex-Loeser panel (see fig. 7) is 37.7 centimeters wide, which is more than adequate for a single predella panel (the four known predella panels average 35 centimeters in width), but the Gardner panel is only 55.6 centimeters wide, insufficient for two panels to have stood beneath it. If the ex-Loeser and Gardner panels formed part of a pentaptych, the combined width of the five panels can be estimated as approximately 208 centimeters, which would have been an appropriate width for six predella panels (about 210 centimeters). It is not, however, completely certain that the Gardner and ex-Loeser panels originally stood together in the same altarpiece, pace Offner. The Gardner Virgin bears traces of batten nails at the level of the spring of its framing arch; no impressions of batten nails are apparent anywhere on the surface of the ex-Loeser Saint Dominic, which has been transferred to a new wood support but retains a beautifully preserved paint surface. ↩︎

-

Offner, Richard. A Critical and Historical Corpus of Florentine Painting: The Fourteenth Century. Sec. 3, vol. 5, Master of San Martino alla Palma; Assistant of Daddi; Master of the Fabriano Altarpiece. New York: Institute of Fine Arts, New York University, 1947., 65–69; and Offner, Richard. A Critical and Historical Corpus of Florentine Painting: The Fourteenth Century. Sec. 3, vol. 3, The Works of Bernardo Daddi. Ed. Miklós Boskovits. Florence: Giunti, 1989., 200–205. ↩︎

-

Boskovits, Miklós. Frühe italienische Malerei: Gemäldegalerie Berlin, Katalog der Gemälde. Berlin: Mann, 1988., 27–28. ↩︎

-

Inv. no. 8345. ↩︎

-

Carl Strehlke, verbal communication with the author. ↩︎

-

Sale, Artcurial, Paris, March 23, 2022, lot 30. ↩︎

-

For the dating of this altarpiece, see Skaug, Erling S. Punch Marks from Giotto to Fra Angelico: Attribution, Chronology, and Workshop Relationships in Tuscan Panel Painting, with Particular Consideration to Florence, c. 1330–1430. 2 vols. Oslo: International Institute for Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works—Nordic Group, 1994., 1:104, 111–14; 2: no. 5.3; and Tartuferi, Angelo. Bernardo Daddi: L’incoronazione di Santa Maria Novella. Livorno: Sillabe, 2000., 55–58. Both authors favor a dating after the 1344 altarpiece from the Capella degli Spagnuoli in Santa Maria Novella. ↩︎

-

Skaug, Erling S. Punch Marks from Giotto to Fra Angelico: Attribution, Chronology, and Workshop Relationships in Tuscan Panel Painting, with Particular Consideration to Florence, c. 1330–1430. 2 vols. Oslo: International Institute for Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works—Nordic Group, 1994., 1:102, 111–14; 2: no. 5.3. Skaug situates this painting in the middle of his “sequence D” (i.e., after 1337) but before the dated altarpiece of 1344 from the Capella degli Spagnuoli. ↩︎

-

Cited in Offner, Richard. A Critical and Historical Corpus of Florentine Painting: The Fourteenth Century. Sec. 3, vol. 3, The Works of Bernardo Daddi. Ed. Miklós Boskovits. Florence: Giunti, 1989., 188. ↩︎

-

Vasari, Giorgio. Le vite de’ più eccellenti pittori, scultori ed architettori. With new annotations and comments by Gaetano Milanesi. 9 vols. Florence: G. C. Sansoni, 1878–85., 1:673. ↩︎

-

Vasari, Giorgio. Le vite de’ più eccellenti pittori, scultori ed architettori. With new annotations and comments by Gaetano Milanesi. 9 vols. Florence: G. C. Sansoni, 1878–85., 2:507. ↩︎