Rev. John Fuller Russell (1814–1884), Eagle House, Enfield, England, by 1854–85; sale, Christie’s, London, April 18, 1885, lot 108 (as Taddeo Gaddi); Henry Wagner (1840–1926), London; sale, Christie’s, London, January 16, 1925, lot 58 (as Bernardo Daddi); Galerie Mori, Paris; Maitland Fuller Griggs (1872–1943), New York, 1925

The panel support, of a vertical grain, is approximately 2 centimeters thick and exhibits a pronounced convex warp; chisel and gouge marks on the reverse (fig. 1) suggest that the thickness may be original. The reverse of the panel is beveled along all four edges. While this is unusual for fourteenth-century panels, there is no firm evidence that the beveling is the result of a later intervention. A small rectangular plug in the upper-right corner of the reverse is a modern repair. All the raised frame moldings are carved in one with the support rather than applied to it, an archaic carpentry technique more common in the thirteenth than in the fourteenth century. The moldings have all been liberally releafed over original bolus and gilding, though much original gold is still in evidence along the uppermost outer-frame molding and the top third of the lateral moldings above the spring of the interior arch; gilding on the left molding, for example, is nearly intact in this area. The new gold has been articulated with an incised craquelure. The two roundels contained within the spandrels outside the arch are modern inserts, as are the spiral colonettes supporting the arch: the capitals and bases are original and are carved out of the wood of the support, but the colonettes are nailed in place (with modern wire nails) and cover original paint surface.

Notwithstanding earlier published reports to the contrary, the paint surface is generally in a beautiful state of preservation, though it is interrupted by relatively large, discrete flaking losses in the center of the composition and by scattered local abrasions, especially among the haloes of the angels on either side of the throne. The lacunae (fig. 2) affect the trapezoidal area between the torsos of Christ and the Virgin, much of the area of the Virgin’s dress below her knees, the left edge of the cloth of honor, and two areas in the foreground: one at the foot of the viol-playing angel at lower right and one on the riser of the throne. These were enlarged and deepened in the course of a harsh cleaning by Andrew Petryn in 1967 and have been filled and inpainted in the most recent conservation treatment by Irma Passeri in 2015–16. A circular loss at the top of the throne above the head of Christ seems to have been provoked by early removal and repair of a knot in the panel support; it, too, has now been filled and inpainted. The engraved dragon or bird designs filling the spandrels within the cusping of the arch and outside the arch are exceptionally well preserved, but the blue and red paint highlighting them appears to be a later addition.

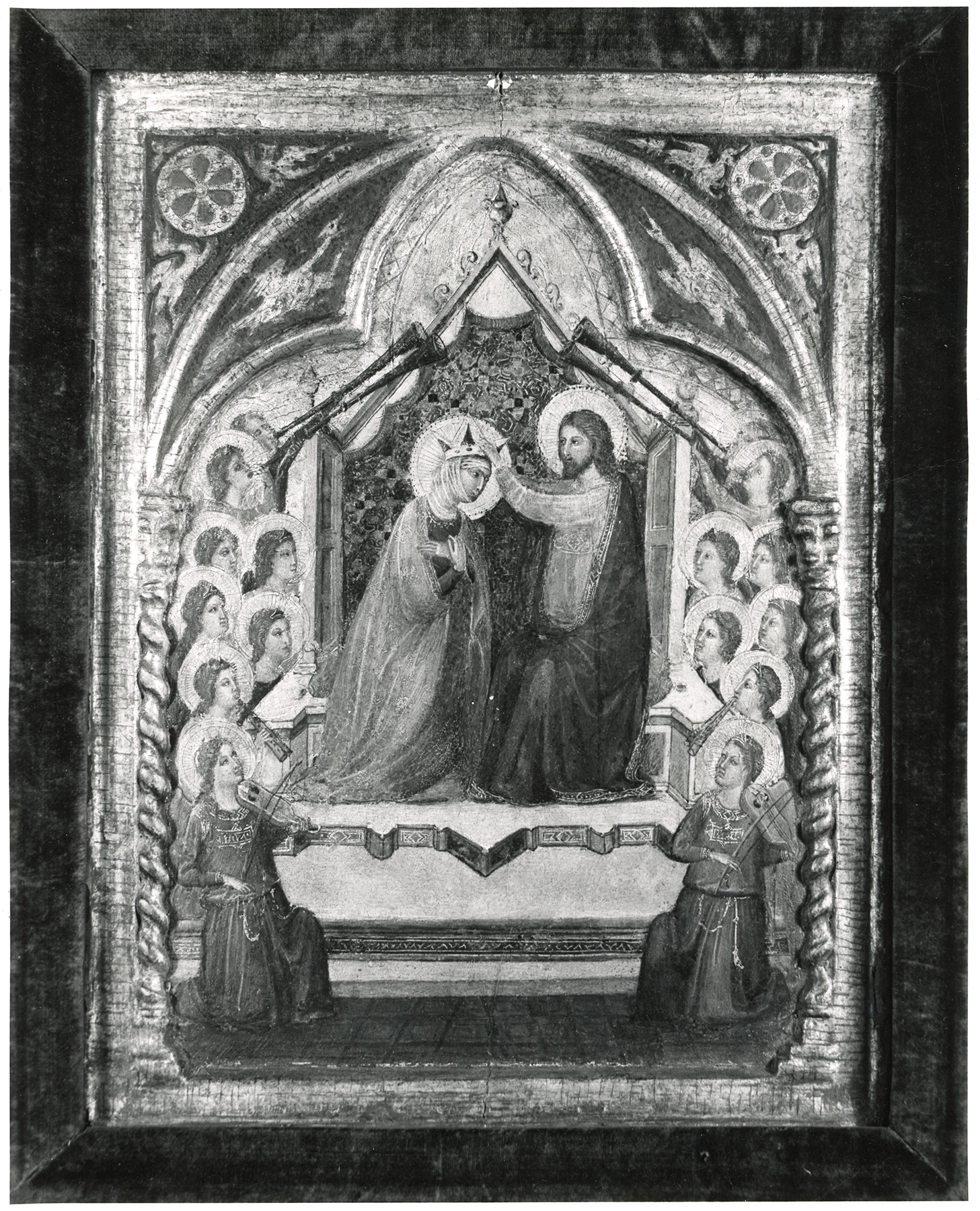

When the eminent German historian Gustav Waagen saw this panel in the collection of Rev. John Fuller Russell in 1854, he remarked upon its damaged state, commenting that only in the “fifteen [sic] angels” it depicts could one fully appreciate “the fine character of the master.”1 He identified this master as the Sienese painter Taddeo di Bartolo, possibly in recognition of the clarity and brilliance of his palette but perhaps as a slip of the pen, for only three years later, in 1857, Fuller Russell lent the panel to the Art Treasures of Great Britain exhibition in Manchester, England, with an attribution to Taddeo Gaddi, and it is difficult to imagine who, in the brief intervening period, might have corrected Waagen’s attribution. The painting retained its attribution to Taddeo Gaddi at the 1877 exhibition of the Royal Academy, London, at the sale of Fuller Russell’s estate in 1885, and again when it was lent by Henry Wagner to the 1903–4 exhibition Early Italian Art at Burlington House, London. By the time it appeared at the sale of Wagner’s collection in London in January 1925, however, the attribution had been changed to Bernardo Daddi and was quickly corrected, in 1927, by Richard Offner to Jacopo del Casentino.2 Raimond van Marle’s opinion that the panel might be by the Master of the Saint George Codex was formulated before he had read Offner’s arguments and was almost immediately withdrawn.3

Subsequent references to the panel have, with only two significant exceptions, been concerned with debating an ascription either directly to Jacopo del Casentino or to his workshop or following. This vacillation was inspired in the first instance by Offner’s summary remarks of 1927, at which time he knew the panel only from a photograph that to him revealed “restoration of what would seem a rather weak original. The types commit it to Jacopo’s late period.”4 This restored state is recorded in the photograph he published in the 1930 volume of the Corpus (fig. 3), where he classified the painting as “shop of Jacopo del Casentino.”5 Forty years later, Charles Seymour, Jr., retained this classification with an expression of doubt, explaining that “because of its poor state the panel is difficult to attribute . . . it is possibly by a miniaturist. After cleaning, even the shop of Jacopo del Casentino seems remote. Probably a provincial artist is involved here.”6 Erling Skaug, responding to the appearance of a totally unfamiliar punch mark along the upper-left margin of the gold ground, concurred with Seymour in omitting the panel from his discussion of Jacopo del Casentino’s attributions and chronology.7

Offner may perhaps be excused for his dismissive estimation of the Griggs Coronation, as in the regilt and heavily repainted state in which he knew the painting, its quality was stiffened and caricatured. Furthermore, since he believed its figure types corresponded to Jacopo del Casentino’s late style, its apparently diminished quality could only logically be explained by relegating it to the status of an imitative workshop production. As Miklós Boskovits observed, cleaning of the panel in 1967, though drastic, revealed it to be an autograph work by Jacopo del Casentino.8 It is difficult to account for Seymour’s exaggerated contempt of the panel’s cleaned state. His focus on the extent of losses in the center of the composition ignored the fact that nearly the entirety of the paint surface, other than the discrete areas of total loss, is unusually well preserved, and that these passages without exception are of a remarkably elevated delicacy and sensitivity. Furthermore, while Seymour was aggressive in pursuing the removal of repaints on this panel, he was apparently unaware of the extent of modern gilding on its frame and surface or of the fact that the spiral colonettes, the inserted disks in the outer spandrels, and the colored reveals in the decoration of both the inner and outer spandrels are modern additions.

While the quality of the Griggs Coronation certainly justifies its classification as a wholly autograph work by Jacopo del Casentino, it also precludes the possibility of associating it with the artist’s late style, as Offner proposed. The nearly square proportions and compressed, planar composition of the panel may be compared to the signed Cagnola Triptych by Jacopo now in the Gallerie degli Uffizi, Florence (fig. 4), considered one of the artist’s earliest surviving works. An early date is further implied by the archaic structure of its carpentry, with its frame moldings carved in one with the panel support rather than applied to it as independently engaged members, and by the dragon or bird motifs stippled into the inner and outer spandrels of the panel’s frame moldings: these reappear, though on a considerably larger scale, in only one other work by Jacopo, the pentaptych now divided between the Musée Royaux des Beaux-Arts de Belgique, Brussels, and the Alana Collection, Newark, Delaware, correctly dated by Boskovits before 1330.9 A related, more complex, and certainly later version of the Coronation, now in the Kunstmuseum Bern, Switzerland (fig. 5), reveals the characteristics of Jacopo’s mature style. The figure types in that painting are thinner and more stiffly columnar, more restrained and solemn than those in the Griggs Coronation, while the vertically elongated format of its composition, the updated architecture of its throne, and the denser arrangement of saints and angels crowded around it clearly reflect the principles of design made fashionable in Florence by Bernardo Daddi and Puccio di Simone in the early 1340s.10 As in the Griggs panel, the haloes and borders of the gold ground in the Bern Coronation are articulated by inscribed decoration rather than motif punches, so neither work can be inserted into the relatively precise chronology of that aspect of the artist’s development chronicled by Skaug. It may be claimed, however, that the engraved pattern of a cusped arcade decorating the margins of the picture field in the Bern work imitates a later decorative fashion than does the simple geometric border of the Griggs panel, which follows thirteenth- rather than fourteenth-century models.

The precise timing of Jacopo del Casentino’s early career remains much in doubt, but it has been difficult for scholars to propose credible arguments for dating any paintings by him before ca. 1320.11 It is during the third decade of the century that his works most closely resemble those of two of his contemporaries with whom he has in the past been confused, Pacino di Bonaguida and the Master of the Dominican Effigies, and it is possible that these three artists actively collaborated at that time.12 The conventional explanation for these areas of apparent stylistic overlap has been to assume that the Master of the Dominican Effigies may have been a follower of Jacopo del Casentino, but it is far more likely that these two painters were near contemporaries and that both may have been followers of Pacino di Bonaguida or of a contemporary of Pacino’s to whom all three painters were clearly indebted: the Master of Saint Cecilia.13 If the identification of that artist with Taddeo Gaddi’s father, Gaddo Gaddi, is correct, it may be interesting to speculate whether Giorgio Vasari’s assertion that Jacopo del Casentino was trained in the Gaddi workshop, though dismissed by modern scholarship, may have been based on relatively reliable (if slightly garbled) tradition.

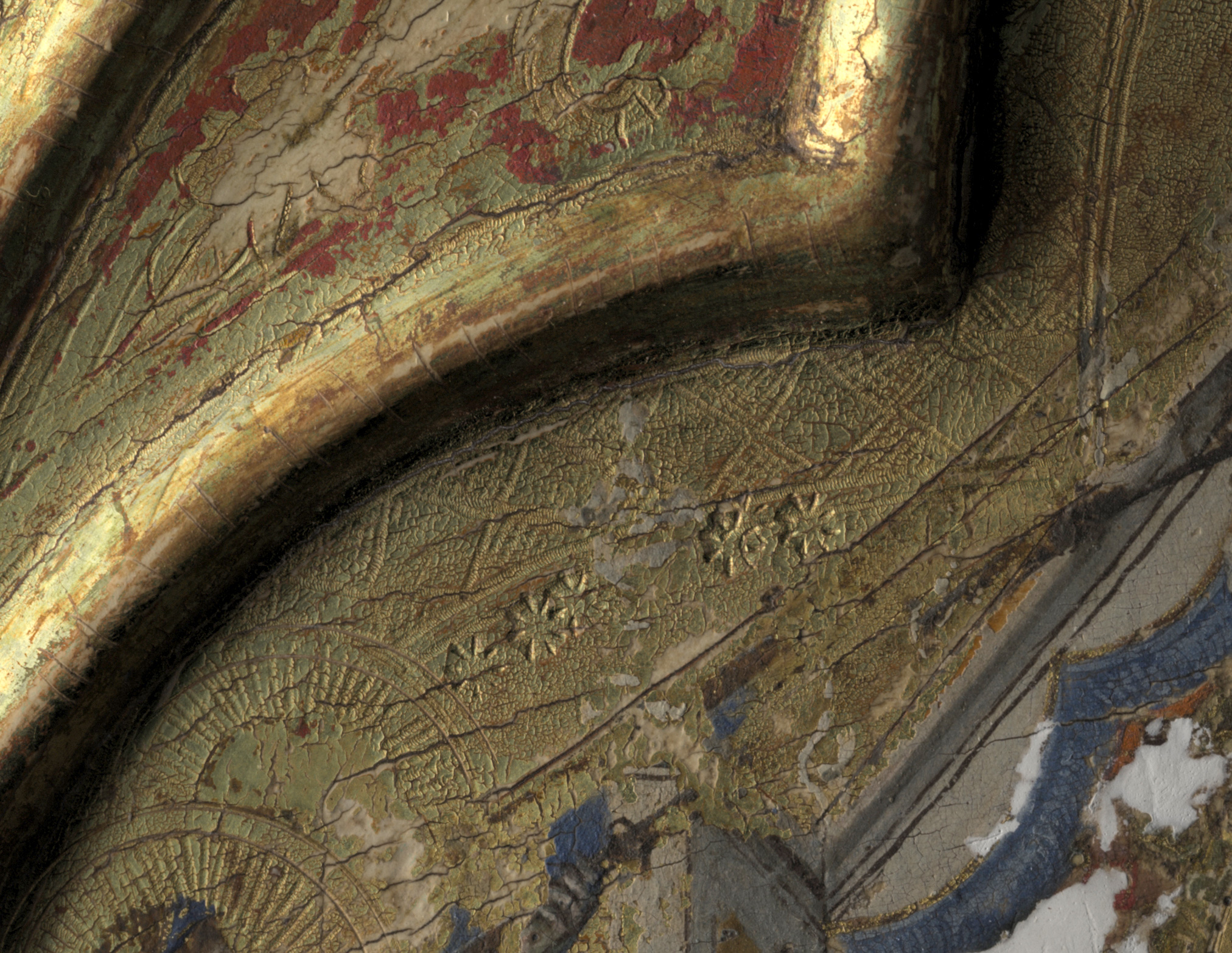

Of further interest to the question of Jacopo del Casentino’s possible training in the workshop of either Gaddo or Taddeo Gaddi may be the identification of the punch strike that appears five times along the border of the first arc of the trefoil in the frame at the left of the Griggs Coronation. The tool was struck so lightly that its impressions are visible only in raking light (fig. 6) and do not interrupt the crackle pattern in the gold created by the stylus ruling of the border pattern. The incomplete impressions were described by Skaug as an “eight-part asterisk . . . unlike Jacopo’s secure punches,” but they do approximate the impressions of another tool catalogued by Skaug that was used exclusively by Taddeo Gaddi in his earliest paintings.14 That Jacopo used this tool so tentatively and discontinued its application after a single arc of the border implies an indecisive or experimental approach that may be yet another indication of an early date for the painting. Similarly tentative are the facts that only one halo among the sixteen angels is decorated with a dotted rim and even this is not dotted along its full perimeter, and that the “perspective” tiling of the foreground continues beneath the first riser of the dais of the throne, revealing an uncertainty in the planning of the composition from the outset.

It remains to be determined whether the claim that the composition of the Griggs Coronation depends upon that of Giotto’s Baroncelli Chapel altarpiece at Santa Croce in Florence necessarily implies a terminus post quem for dating the former, as the Baroncelli altarpiece is generally assumed to have been conceived and executed (whether by Giotto himself or by Taddeo Gaddi working in Giotto’s studio) sometime after Giotto’s return to Florence from Naples in 1333 or 1334.15 It is a convention among historians of early Italian art to mark as the beginning of an iconographic progression the best-known or most accomplished example within the trend, but there exists no documentary or even empirical evidence to support such a convention. It may be evident that a painting like Bernardo Daddi’s Coronation of the Virgin now in the National Gallery, London, makes overt and respectful reference to Giotto’s Baroncelli altarpiece;16 it does not follow that all examples of the subject must be traced back to the same source. Duccio had in fact popularized a closely related version of the Coronation of the Virgin in his stained-glass window on the facade of the cathedral of Siena as early as the 1280s. Accepting an early date for the Griggs Coronation, however, does not necessarily entail positing a direct link between Jacopo del Casentino and Sienese prototypes. The diffusion of the motif throughout Tuscany and central Italy at the end of the thirteenth and beginning of the fourteenth centuries must have been broader and more immediate than can be demonstrated through the rare surviving examples known today. At the same time, it may not be a coincidence that numerous scholars have remarked on Sienese sources for the compositional motifs of several Virgin and Child paintings by Jacopo. Furthermore, close parallels for the unusual projections at the foot of the throne in the Griggs Coronation are to be found among earlier Ducciesque rather than Florentine paintings, and Skaug has observed of Jacopo that he is alone among Florentine painters in the first half of the trecento in having been influenced by the Sienese style of cluster punchwork.17

The original purpose or function of the Griggs Coronation is unclear. The contention that it might have been the “upper part of a tabernacle centre”—presumably meaning one of two scenes on the center panel of a tabernacle triptych—cannot be sustained.18 Not only are the outer-frame moldings entirely original (though regilt), but they are also, as has been said, carved in one with the panel support. The panel, therefore, has not been reduced in size nor altered in shape. There is no evidence of hinges ever having been applied at either side. The excellent state of preservation of the paint surface would argue against the panel’s having been used as a pax, which its size and proportions might otherwise suggest. It is possible that it may have been designed to be inserted into a larger frame or structure, such as a marble tabernacle or precious-metal reliquary. Such an eventuality could explain the large paint losses being restricted to the center of the panel, along the line of greatest stress where the warpage of the panel would have been constrained by its inflexible surround, and it may also explain the beveled reverse of the panel, if indeed this is original. It is also unclear what function might have been served by the circular inserts in the outer spandrels of the frame.19 These could have been filled by cabochons or verre églomisé roundels, or by relics sealed behind glass; surviving physical evidence is inconclusive. —LK

Published references

Waagen, [Gustav]. Treasures of Art in Great Britain. 3 vols. London: John Murray, 1854., 2:462; Exhibition of Works by the Old Masters. Exh. cat. London: William Clowes and Sons, 1877., 28, no. 156; Exhibition of Early Italian Art from 1300 to 1550. Exh. cat. London: New Gallery, 1893., 10, no. 52; Offner, Richard. Studies in Florentine Painting: The Fourteenth Century. New York: Sherman, 1927., 33; Offner, Richard. A Critical and Historical Corpus of Florentine Painting: The Fourteenth Century. Sec. 3, vol. 2, pt. 2, Works Attributed to Jacopo del Casentino. New York: Institute of Fine Arts, New York University, 1930., 93, 170, pl. 72; van Marle, Raimond. “Le Maître du Codex de Saint Georges et la peinture française du XIVe siècle.” Gazette des beaux-arts, 6th ser., 5, no. 1 (January 1931): 1–28., 17; Berenson, Bernard. Italian Pictures of the Renaissance: A List of the Principal Artists and Their Works with an Index of Places. Oxford: Clarendon, 1932., 272; Ameisenowa, Sofia. “Opere inedite del ‘Maestro del Codice di S. Giorgio.’” Rivista d’arte 21 (1939): 97–125., 120; Offner, Richard. A Critical and Historical Corpus of Florentine Painting: The Fourteenth Century. Sec. 3, vol. 5, Master of San Martino alla Palma; Assistant of Daddi; Master of the Fabriano Altarpiece. New York: Institute of Fine Arts, New York University, 1947., 247–48; Offner, Richard. A Critical and Historical Corpus of Florentine Painting: The Fourteenth Century. Sec. 3, vol. 7, The Biadaiolo Illuminator; Master of the Dominican Effigies. New York: Institute of Fine Arts, New York University, 1957., 105n2, 151; Berenson, Bernard. Italian Pictures of the Renaissance, A List of the Principal Artists and Their Works with an Index of Places: The Florentine School. 2 vols. London: Phaidon, 1963., 1:102; Seymour, Charles, Jr. Early Italian Paintings in the Yale University Art Gallery. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1970., 46–47, 307, no. 28; Gosebruch, Martin. “Sulla necessità di colmare la lacuna tra Padova e le cappelle di S. Croce nella biografia artistica di Giotto.” In Giotto e il suo tempo, ed. Mario Salmi, 233–51. Rome: De Luca, 1971., 247; Fredericksen, Burton B., and Federico Zeri. Census of Pre-Nineteenth-Century Italian Paintings in North American Public Collections. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1972., 600; Offner, Richard. A Critical and Historical Corpus of Florentine Painting. Sec. 3, vol. 2, Elder Contemporaries of Bernardo Daddi. Ed. Miklós Boskovits. Florence: Giunti, 1987., 10, 387, 522–23; Pergam, Elizabeth A. The Manchester Art Treasures Exhibition of 1857: Entrepreneurs, Connoisseurs and the Public. Farnham, Surrey, England: Ashgate, 2011., 140–41, 188n13, 219, 312; Skaug, Erling S. Punch Marks from Giotto to Fra Angelico: Attribution, Chronology, and Workshop Relationships in Tuscan Panel Painting, with Particular Consideration to Florence, c. 1330–1430. 2 vols. Oslo: International Institute for Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works—Nordic Group, 1994., 1:122n230

Notes

-

Waagen, [Gustav]. Treasures of Art in Great Britain. 3 vols. London: John Murray, 1854., 2:462. ↩︎

-

Offner, Richard. Studies in Florentine Painting: The Fourteenth Century. New York: Sherman, 1927., 33. ↩︎

-

van Marle, Raimond. “Le Maître du Codex de Saint Georges et la peinture française du XIVe siècle.” Gazette des beaux-arts, 6th ser., 5, no. 1 (January 1931): 1–28., 17. ↩︎

-

Offner, Richard. Studies in Florentine Painting: The Fourteenth Century. New York: Sherman, 1927., 33. ↩︎

-

Offner, Richard. A Critical and Historical Corpus of Florentine Painting: The Fourteenth Century. Sec. 3, vol. 2, pt. 2, Works Attributed to Jacopo del Casentino. New York: Institute of Fine Arts, New York University, 1930., pl. 72. ↩︎

-

Seymour, Charles, Jr. Early Italian Paintings in the Yale University Art Gallery. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1970., 47. ↩︎

-

Skaug, Erling S. Punch Marks from Giotto to Fra Angelico: Attribution, Chronology, and Workshop Relationships in Tuscan Panel Painting, with Particular Consideration to Florence, c. 1330–1430. 2 vols. Oslo: International Institute for Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works—Nordic Group, 1994., 1:122n230. ↩︎

-

Offner, Richard. A Critical and Historical Corpus of Florentine Painting. Sec. 3, vol. 2, Elder Contemporaries of Bernardo Daddi. Ed. Miklós Boskovits. Florence: Giunti, 1987., 10. ↩︎

-

Offner, Richard. A Critical and Historical Corpus of Florentine Painting: The Fourteenth Century. Sec. 3, vol. 9, The Painters of the Miniaturist Tendency. Ed. Miklós Boskovits. Florence: Giunti, 1984., 58. For the Brussels panel, see inv. no. 794; for the Alana, see inv. no. 2001.04a–d. ↩︎

-

See Fehlmann, Marc, and Gaudenz Freuler. Die Sammlung Adolf von Stürler: In Memoriam Eduard Hüttinger (1926–1998). Exh. cat. Schriftenreihe Kunstmuseum Bern 7. Bern, Switzerland: Kunstmuseum Bern, 2001., 52–57, where this painting is implausibly dated 1325–30. ↩︎

-

A proposal by Emanuele Zappasodi to associate the five panels formerly ascribed to the Master of the Spinola Annunciation with the earliest career of Jacopo del Casentino, presumably between 1310 and 1320, has met with some but not universal approval; see Zappasodi, Emanuele. “La più antica decorazione della sagrestia-capitolo di Santa Croce.” Ricerche di storia dell’arte 102 (2010): 49–64.. ↩︎

-

A case in point that deserves much closer study in this regard is the illuminated Laudario of the Compagnia di Sant’Egidio (now at the Biblioteca Nazionale, Florence, inv. no. B.R. 19), twelve of whose miniatures are attributed by Offner and Boskovits to the Master of the Dominican Effigies, but several of which have persistently, and perhaps correctly, been associated with Jacopo del Casentino instead; see Offner, Richard. A Critical and Historical Corpus of Florentine Painting. Sec. 3, vol. 2, Elder Contemporaries of Bernardo Daddi. Ed. Miklós Boskovits. Florence: Giunti, 1987., 326–33. While Boskovits (in Offner, Richard. A Critical and Historical Corpus of Florentine Painting. Sec. 3, vol. 2, Elder Contemporaries of Bernardo Daddi. Ed. Miklós Boskovits. Florence: Giunti, 1987., 10), ignoring then-recent scholarship, dismisses these attributions as negligent, it is not clear that they are wholly unfounded. ↩︎

-

For more on this artist, see Master of Saint Cecilia, Virgin and Child. ↩︎

-

Skaug, Erling S. Punch Marks from Giotto to Fra Angelico: Attribution, Chronology, and Workshop Relationships in Tuscan Panel Painting, with Particular Consideration to Florence, c. 1330–1430. 2 vols. Oslo: International Institute for Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works—Nordic Group, 1994., 2: no. 326. A photograph of this punch impression included in Frinta, Mojmír S. Punched Decoration on Late Medieval Panel and Miniature Painting. Vol. 1, Catalogue Raisonné of All Punch Shapes. Prague: Maxdorf, 1998., 166, no. Dda12, taken from Gaddi’s Virgin in the Musée des Beaux-Arts, Strasbourg (inv. no. 202), is even closer to the impressions on the Griggs Coronation due to the angle at which the tool was held during the strike; one side of the impression is incomplete. For further discussion of confusion between Taddeo Gaddi’s and Jacopo del Casentino’s earliest punch tools, see Skaug, Erling S. Punch Marks from Giotto to Fra Angelico: Attribution, Chronology, and Workshop Relationships in Tuscan Panel Painting, with Particular Consideration to Florence, c. 1330–1430. 2 vols. Oslo: International Institute for Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works—Nordic Group, 1994., 1:94, 122. ↩︎

-

For the association of the Yale Coronation with the Baroncelli Chapel altarpiece, see Ameisenowa, Sofia. “Opere inedite del ‘Maestro del Codice di S. Giorgio.’” Rivista d’arte 21 (1939): 97–125., 120. ↩︎

-

Inv. no. NG6599, https://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/paintings/bernardo-daddi-the-coronation-of-the-virgin. ↩︎

-

Skaug, Erling S. Punch Marks from Giotto to Fra Angelico: Attribution, Chronology, and Workshop Relationships in Tuscan Panel Painting, with Particular Consideration to Florence, c. 1330–1430. 2 vols. Oslo: International Institute for Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works—Nordic Group, 1994., 1:125–26. ↩︎

-

Offner, Richard. A Critical and Historical Corpus of Florentine Painting: The Fourteenth Century. Sec. 3, vol. 7, The Biadaiolo Illuminator; Master of the Dominican Effigies. New York: Institute of Fine Arts, New York University, 1957., 105n2. ↩︎

-

The two punch tools appearing among the inscribed decoration on these roundels—a circle and a five-petaled rosette—are catalogued by Frinta in a number of early twentieth-century restorations, most of which appeared on the art market in Florence; see Frinta, Mojmír S. Punched Decoration on Late Medieval Panel and Miniature Painting. Vol. 1, Catalogue Raisonné of All Punch Shapes. Prague: Maxdorf, 1998., 443, no. Ka19dN. Two of them, the present painting and another in the National Gallery of Art, Washingon, D.C., by Grifo di Tancredi (inv. no. 1937.1.2a–c), were purchased in Paris in 1925 and 1919, respectively, and may ultimately lead to identification of the restorer’s studio in which the work was done. ↩︎