above Saint James, S[anctus] IACHOB[us]; above Saint John the Baptist, S[anctus] IOHA[n]ES; above Saint Peter, S[anctus] PETRU[s]; above Saint Francis, S[anctus] Fra[n]CISC[us]

James Jackson Jarves (1818–1888), Florence, by 1859

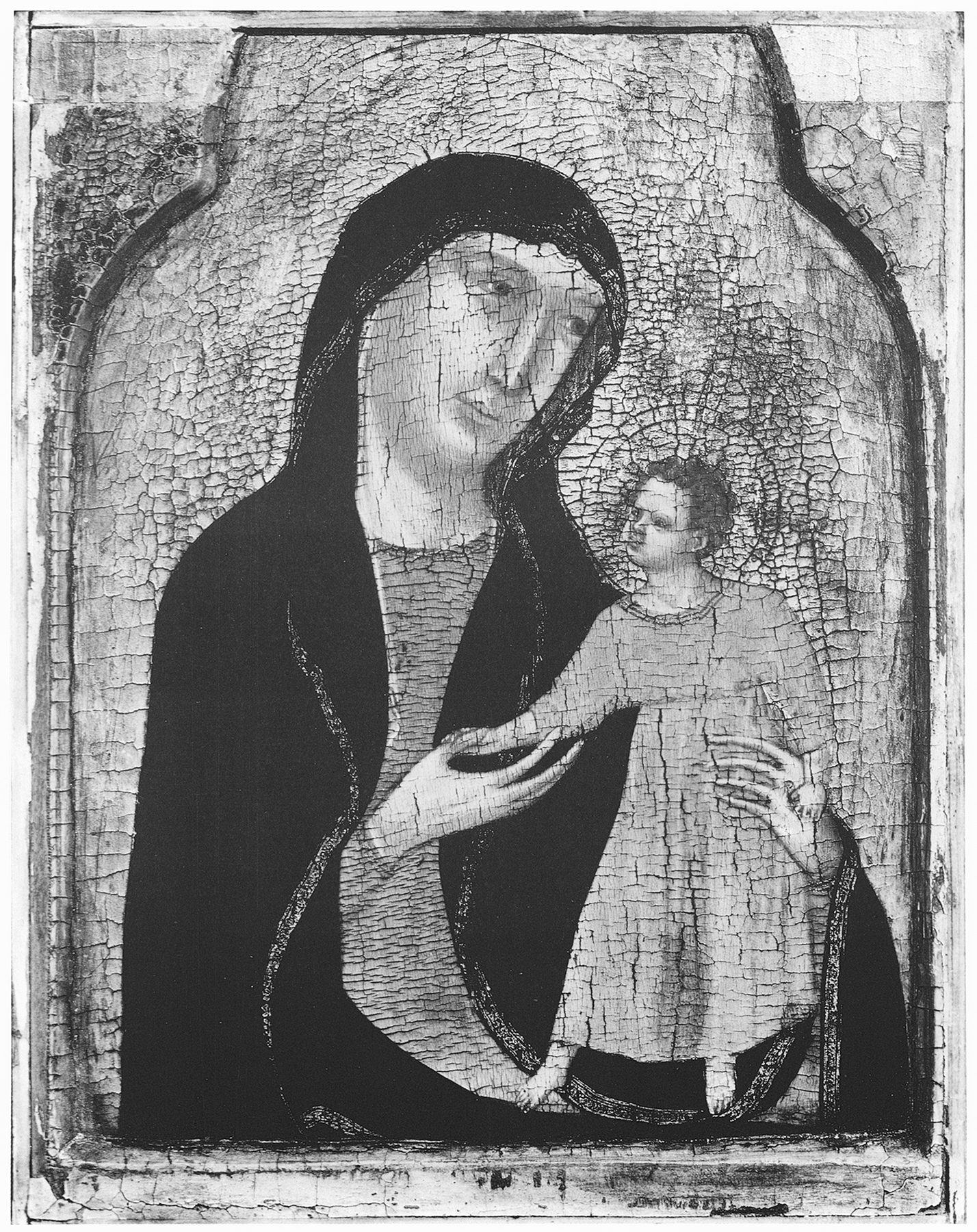

The panel support, ranging from 2 to 2.2 centimeters in thickness, has a horizontal wood grain. It has been waxed and cradled but apparently not thinned. A join, now open, between the pediment and main panel runs across the central image at the level of the Virgin’s forehead. The pediment is truncated at the top. Horizontal splits at either end of the support, extending 37 centimeters in at left and 27 centimeters in at right, have resulted in minor paint loss, as have three nails along the central vertical axis of the composition, where a batten was once affixed to the reverse. The gold ground is heavily abraded but the paint, aside from minor scattered losses, is well preserved. The losses primarily affect the figure of Saint James at left. The Virgin and Child, the cloth of honor behind them, and Saints Peter and Francis are particularly well preserved.

The engaged frame moldings are original but are missing a capping molding along the pediment. An earlier restoration had added moldings, 4 centimeters wide, to the surface at the left and right ends of the panel to close the circuit of the original moldings. Removal of these additions in the 1950s revealed unusually well-preserved original gilding beneath, as well as painted black borders approximately 2.2 centimeters wide, which are decorated with painted white rhombuses. As the width of these borders is approximately the same as that of the flat surface of the original moldings, there is a presumption that they may be complete. There is no visible evidence of modern cutting at the sides of the panel, other than damage to the upper and lower moldings to enable the lateral additions to be slotted into them. It is not clear, therefore, whether the dossal originally terminated in buttresses or slender moldings applied as capping strips along the outer edges.

Following the usual garden-variety attributions to which nearly all late thirteenth- and early fourteenth-century paintings were subjected, this dossal depicting the Virgin and Child with Saints James, John the Baptist, Peter, and Francis—always esteemed for its quality and for its rarity as a complete, unaltered structure—was first associated by Roberto Longhi and Edward Garrison with the anonymous Cimabuesque artist known as the Master of Varlungo.1 It has invariably appeared under this name in art-historical publications of the past seventy years, with two notable exceptions. Charles Seymour, Jr., preferred to catalogue it generically as “Tuscan school,” describing its artist as “more likely to have worked in Pisa than in Lucca or Florence.”2 He referred to similarities with the work of Deodato Orlandi, to whom the painting had once been assigned.3 Orlandi was also thought to have been the author of a retable with Saint Michael and four standing saints once in the Fiammingo collection, Rome, that had subsequently, like the Yale dossal, been reattributed to the Master of Varlungo. Angelo Tartuferi acknowledged the close association of the ex-Fiammingo and Yale dossals but argued that neither was likely to be the work of the Master of Varlungo.4 Tartuferi maintained that in no other paintings did the Master of Varlungo, a follower of the Magdalen Master much influenced by Cimabue, reveal so intimate and conscientious an awareness of the earliest innovations of the young Giotto in Florence, prior to the latter’s departure to work in Assisi. Unable to reconcile this intellectual shift of allegiances with the natural stylistic maturation of a single personality, Tartuferi coined an epithet of convenience, the “Pseudo-Master of Varlungo,” to describe the Yale and ex-Fiammingo paintings, along with a related work in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.5 Daniela Parenti rejected this distinction within the group of works associated with the Master of Varlungo, which she viewed as of sufficiently high quality to justify the wide range of stylistic development that had troubled Tartuferi.6

While it is possible to agree with Parenti that the Master of Varlungo group reveals an essential homogeneity of imagery and technique, notwithstanding its evident development of style, it is necessary to acknowledge that Tartuferi was correct in dissociating the Yale dossal from the other paintings by that Master. The artist’s command of the three-dimensional representation of forms in the present painting—in the articulation of anatomy, the twisting positions of bodies in space, and the blending of highlights into, rather than on top of, local colors—bears a more telling relation to trecento than duecento practice and has no point of contact within the Master of Varlungo group. His use of a pastel color range is radically different from the severely limited palette of other works by the Master of Varlungo (including Yale’s Virgin and Child Enthroned with Two Angels), and his successful evocation of emotional tension is all but unparalleled in thirteenth-century Florence outside the works of Cimabue and Giotto. Only one other painting is so exactly like the Yale dossal in all these respects, and is sufficiently close to it in Morellian detail as well, that it can be unequivocally recognized as by the same hand: a small Virgin and Child in a private collection in Bologna (fig. 1), first published by Carlo Volpe as an early work by the Florentine artist Lippo di Benivieni.7 The Christ Child in that painting is clad, unconventionally, in a lilac tunic that is the same surprising color as the Baptist’s cloak in the Yale dossal and that reappears so conspicuously in other works by Lippo di Benivieni, such as the Lamentation in the Museo Civico, Pistoia. Parallels for the simple oval structure of the Virgin’s head or the solid, almost blocklike construction of the Christ Child and His lively, animated pose are found in other paintings from the first half of Lippo’s career, such as the triptych from the Contini Bonacossi Collection at the Gallerie degli Uffizi, Florence, or the center panels from the Alessandri and Bartolini Salimbeni polyptychs, both signed works.8 Even the intensely knit brow of the Baptist in the Yale dossal may be recognized as a germinal form of the expressive saints so characteristic of Lippo di Benivieni’s eccentric, mature production.

Lippo di Benivieni has been described by Miklós Boskovits as “undoubtedly one of the major personalities of Florentine Trecento painting. He represents its most refined and poetic aspect, but also one of its highest achievements in the expression of human feeling and in the observation of naturalistic detail.”9 The earliest document referring to him is dated 1296, when he accepted the letters of indenture for a pupil in his shop and may therefore be presumed to have previously been active for some time. Initial reconstructions of his oeuvre by Richard Offner and Carlo Volpe concentrated on paintings clearly executed within the first two decades of the fourteenth century. Even the small Bologna Virgin and Child was dated by Volpe no earlier than ca. 1300, in recognition of its primacy within a logical chronological sequence of Lippo’s work but lacking any positive internal evidence to associate it with duecento Florentine style.10 Boskovits pushed its dating back into the last decade of the thirteenth century, alongside a series of small narrative panels with scenes of the Passion, bringing the known works by the painter and their significance more closely in line with the scant available documentary information about his life.11 Recovery of the Yale dossal as a still-earlier work, probably painted close to 1290, anchors those documents in a compelling visual record. The other end of Lippo’s career has yet to be clarified in the same way. While the last certain documentary mention of his name occurs in 1316, there is some evidence that he may still have been active in 1327 or later. At that point in his career, he seems to have been prepared to absorb the influence of painters like the young Bernardo Daddi and two artists in the latter’s immediate orbit: the Master of San Martino alla Palma and the so-called Maestro Daddesco. A large triptych in the Alana Collection (fig. 2),12 Newark, Delaware, published alternatively as the work of Bernardo Daddi or the Master of San Martino alla Palma, is instead to be attributed to Lippo di Benivieni as probably his latest surviving painting, shortly postdating the exceptional Lamentation over the Dead Christ in the Harvard Art Museums, Cambridge, Massachusetts.13 Thus revealed, the full sweep of his career affords Lippo di Benivieni a stature hardly less significant than that of his slightly older Florentine contemporary, the Master of Saint Cecilia.14 —LK

Published References

Jarves, James Jackson. Descriptive Catalogue of “Old Masters” Collected by James J. Jarves to Illustrate the History of Painting from A.D. 1200 to the Best Periods of Italian Art. Cambridge, Mass.: H. O. Houghton, 1860., 43, no. 14; Jarves, James Jackson. Art Studies: The “Old Masters” of Italy; Painting. New York: Derby and Jackson, 1861., pl. C, fig. 9; Sturgis, Russell, Jr. Manual of the Jarves Collection of Early Italian Pictures. New Haven: Yale College, 1868., 27, no. 13; W. F. Brown, Boston. Catalogue of the Jarves Collection of Early Italian Pictures. Sale cat. November 9, 1871., 13, no. 13; Rankin, William. “Some Early Italian Pictures in the Jarves Collection of the Yale School of Fine Arts at New Haven.” American Journal of Archaeology 10, no. 2 (April–June 1895): 137–51., 139, no. 13; Rankin, William. Notes on the Collections of Old Masters at Yale University, the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, the Fogg Museum of Harvard University. Wellesley, Mass.: Department of Art, Wellesley College, 1905., 7, no. 13; Sirén, Osvald. “Trecento Pictures in American Collections—I.” Burlington Magazine 14, no. 68 (November 1908): 125–26., 126, pl. 2 (top); Sirén, Osvald. The Earliest Pictures in the Jarves Collection at Yale University. New York: F. F. Sherman, 1915., 279–80, fig. 3; Sirén, Osvald. A Descriptive Catalogue of the Pictures in the Jarves Collection Belonging to Yale University. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1916., 17–18, no. 5; van Marle, Raimond. The Development of the Italian Schools of Painting. Vol. 1. The Hague: M. Nijhoff, 1923., 306–7; Offner, Richard. Italian Primitives at Yale University: Comments and Revisions. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1927., 2; Venturi, Lionello. Pitture italiane in America. 2 vols. Milan: Ulrico Hoepli, 1931., pl. 11; Venturi, Lionello. Italian Paintings in America. Trans. Countess Vanden Heuvel and Charles Marriott. 3 vols. New York: E. Weyhe, 1933., pl. 14; Longhi, Roberto. “Giudizio sul duecento.” Proporzioni 2 (1948): 5–54.; Garrison, Edward B. Italian Romanesque Panel Painting: An Illustrated Index. Florence: Leo S. Olschki, 1949., 161, no. 421; Meiss, Millard. Painting in Florence and Siena after the Black Death: The Arts, Religion, and Society in the Mid-Fourteenth Century. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1951., 47; Seymour, Charles, Jr. Early Italian Paintings in the Yale University Art Gallery. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1970., 16–18, no. 5; Fredericksen, Burton B., and Federico Zeri. Census of Pre-Nineteenth-Century Italian Paintings in North American Public Collections. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1972., 599; Gloria Kury Keach and Ronnie Zakon, in Seymour, Charles, Jr., et al. Italian Primitives: The Case History of a Collection and Its Conservation. Exh. cat. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1972., 10–11, no. 2, figs. 2a–c; Marques, Luiz C. La peinture du duecento en Italie centrale. Paris: Picard, 1987., 286–87; Tartuferi, Angelo. “Dipinti del due e trecento alla mostra ‘Capolavori e Restauri.’” Paragone 38, no. 445 (March 1987): 46–60., 51, 59n24, fig. 61b; Tartuferi, Angelo. La pittura a Firenze nel duecento. Florence: Alberto Bruschi, 1990., 64, 113, no. 233, fig. 233; Previtali, Giovanni. Giotto e la sua bottega. 3rd ed. Milan: Fabbri, 1993., 40, 138n47; Tartuferi, Angelo, and Mario Scalini, eds. L’arte a Firenze nell’età di Dante (1250–1300). Exh. cat. Florence: Giunti, 2004., 63, fig. 23; Parenti, Daniela, and Sara Ragazzini, eds. Jacopo del Casentino e la pittura a Pratovecchio nel secolo di Giotto. Florence: Maschietto, 2014., 86

Notes

-

Longhi, Roberto. “Giudizio sul duecento.” Proporzioni 2 (1948): 5–54.; and Garrison, Edward B. Italian Romanesque Panel Painting: An Illustrated Index. Florence: Leo S. Olschki, 1949., 161, no. 421. For more on this artist, see Master of Varlungo, Virgin and Child Enthroned with Two Angels. ↩︎

-

Seymour, Charles, Jr. Early Italian Paintings in the Yale University Art Gallery. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1970., 16, 18. ↩︎

-

Sirén, Osvald. A Descriptive Catalogue of the Pictures in the Jarves Collection Belonging to Yale University. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1916., 17–18; van Marle, Raimond. The Development of the Italian Schools of Painting. Vol. 1. The Hague: M. Nijhoff, 1923., 306–7; Venturi, Lionello. Pitture italiane in America. 2 vols. Milan: Ulrico Hoepli, 1931., pl. 11; and Venturi, Lionello. Italian Paintings in America. Trans. Countess Vanden Heuvel and Charles Marriott. 3 vols. New York: E. Weyhe, 1933., pl. 14. ↩︎

-

Tartuferi, Angelo. “Dipinti del due e trecento alla mostra ‘Capolavori e Restauri.’” Paragone 38, no. 445 (March 1987): 46–60., 51, 59n24; Tartuferi, Angelo. La pittura a Firenze nel duecento. Florence: Alberto Bruschi, 1990., 64, 113, no. 233; and Tartuferi, Angelo, and Mario Scalini, eds. L’arte a Firenze nell’età di Dante (1250–1300). Exh. cat. Florence: Giunti, 2004., 63, fig. 23. ↩︎

-

Inv. no. 49.39, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/437023. ↩︎

-

Daniela Parenti, in Parenti, Daniela, and Sara Ragazzini, eds. Jacopo del Casentino e la pittura a Pratovecchio nel secolo di Giotto. Florence: Maschietto, 2014., 86. ↩︎

-

Volpe, Carlo. “Frammenti di Lippo di Benivieni.” Paragone 23, no. 267 (1972): 3–13., 9–11; and Offner, Richard. A Critical and Historical Corpus of Florentine Painting: The Fourteenth Century. Sec. 3, vol. 9, The Painters of the Miniaturist Tendency. Ed. Miklós Boskovits. Florence: Giunti, 1984., 169, pl. 42. ↩︎

-

For the Contini Bonacossi triptych, see the Virgin and Child between a Pope and a Bishop at the Gallerie degli Uffizi, Florence,

Contini Bonacossi n. 31, https://www.uffizi.it/en/artworks/lippo-di-benivieni-madonna-with-child. ↩︎ -

Offner, Richard. A Critical and Historical Corpus of Florentine Painting: The Fourteenth Century. Sec. 3, vol. 9, The Painters of the Miniaturist Tendency. Ed. Miklós Boskovits. Florence: Giunti, 1984., 34. ↩︎

-

Volpe, Carlo. “Frammenti di Lippo di Benivieni.” Paragone 23, no. 267 (1972): 3–13., 9–11. ↩︎

-

Offner, Richard. A Critical and Historical Corpus of Florentine Painting: The Fourteenth Century. Sec. 3, vol. 9, The Painters of the Miniaturist Tendency. Ed. Miklós Boskovits. Florence: Giunti, 1984., 169, pl. 42. ↩︎

-

Offner, Richard. A Critical and Historical Corpus of Florentine Painting: The Fourteenth Century. Sec. 3, vol. 5, Bernardo Daddi and His Circle. Ed. Miklós Boskovits. Florence: Giunti, 2001., 557–59. ↩︎

-

Inv. no. 1917.195.A, https://hvrd.art/o/232271. ↩︎

-

On the Master of Saint Cecilia, see Master of Saint Cecilia, Virgin and Child. ↩︎