on scroll carried by Saint Elijah, RESPICE IN FACIEM CHRISTI TU[I]

Richard Morris Hunt (1827–1895); by descent to Richard Howland Hunt (1862–1931); by descent to Richard Carley Hunt (1886–1954), New York, 1931

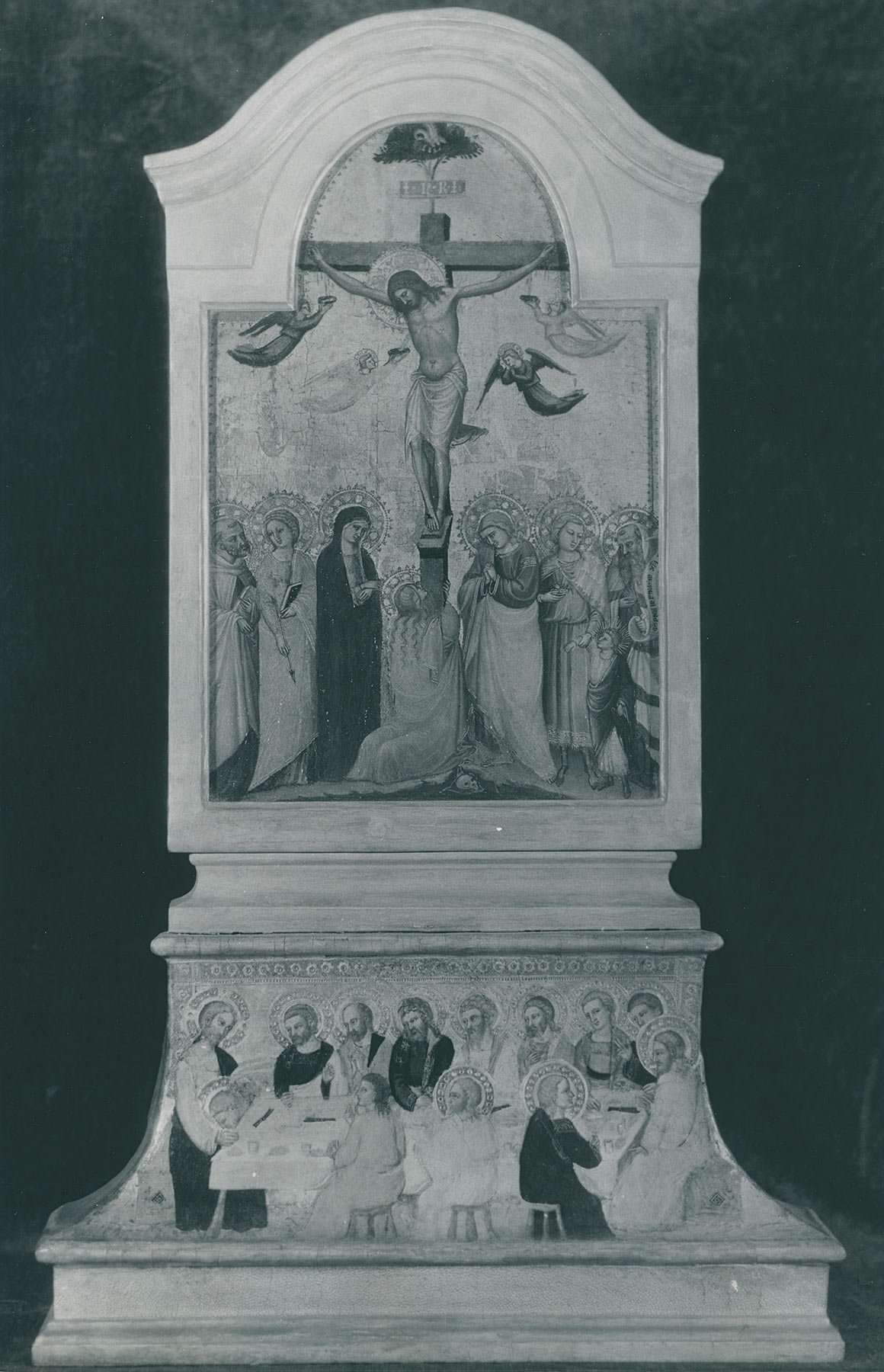

The panel, of a vertical wood grain, has been thinned to between 5 and 8 millimeters, partially marouflaged, and cradled. The composition has been trimmed by at least 10 millimeters on the left and perhaps 2 millimeters on the right, judging from the truncation there of the punched margins of the gold ground. The gilding and paint surface have been lightly abraded throughout but are marred by aggressive cleaning damage, mostly confined to the lower third of the picture field. Pigment has been scraped down to the underlying gesso layer in the Virgin’s blue robe, the lower portion of the Magdalen’s red cloak, and Saint Ursula’s(?) red(?) dress. Losses are also scattered in Saint John’s lilac robe. Other colors are relatively well preserved, although currently dulled by a gray synthetic varnish.

This panel, probably conceived as an independent image for private devotion, shows the Crucified Christ with Mary Magdalen kneeling at the foot of the Cross between the mourning Virgin and Saint John the Evangelist, and four other saints. On the right next to Saint John the Evangelist are Tobias and the Archangel Raphael, whose role as guardian angel and healer made him a favorite subject of such works.1 The Archangel’s gaze is turned toward a bearded saint holding a scroll inscribed with a fragment of Psalm 83: [PROTECTOR NOSTER ASPICE DEUS ET] RESPICE IN FACIEM CHRISTI TU[I] (Behold, O God our protector: and look on the face of thy Christ; Ps. 83:10). The saint wears the gray-and-white mantle with seven horizontal stripes that was the original habit of the Carmelite order, the so-called pallium barratum. The habit was said to have been modeled on the scorched robe left behind by the prophet Elijah when he ascended to heaven in a chariot of fire; according to Carmelite legend, the mantle hung in folds as it dropped through the flames, resulting in fire-branded dark stripes on the exposed parts of the white cloth. The association between fire and Elijah, which is also found in stories related to his birth, may account for the small flame held by the saint, confirming his identification as that prophet.2 The present depiction is highly unusual in Italian painting, however, where representations of Elijah in the main panels of an altarpiece typically show him wearing the new habit with a white scapular and gray tunic adopted by the Carmelite order in 1287 and include no other attribute than a scroll bearing his name. As if to emphasize the contrast between the old and new order, standing opposite Elijah on the other side of the Cross is a younger, beardless saint dressed in the updated version of the Carmelite habit. Although lacking any visible attributes, he is most likely Saint Albert of Trapani (ca. 1240–1307), venerated as the first “modern” founder of the order, long before his official canonization in 1457.3 Next to him, her face turned in his direction, is a young female saint holding a book and an arrow, probably Saint Ursula.4

The panel’s original appearance has been gravely compromised by modern interventions, especially noticeable on the left side where the painted surface has been scraped away in places to reveal the gesso preparation. Some of the faces, like that of the Virgin and Magdalen are all but illegible, while others have been repainted or reduced to the underdrawing. The picture, formerly in the collection of the famous nineteenth-century American architect Richard Morris Hunt, was bequeathed to the Yale University Art Gallery by his heirs in 1937. At the time, it was inserted into a composite modern structure above a tabernacle base by the workshop of Niccolò di Tommaso (fig. 1) (see Workshop of Niccolò di Tommaso, Last Supper) and regarded as a Florentine work from the “middle years” of the fourteenth century.5 The two images were first recognized as independent creations by Richard Offner, who assigned the Crucifixion to Bicci di Lorenzo.6 Charles Seymour, Jr., paid scarce attention to the painting, neglecting even to identify the saints represented, and reiterated the attribution to Bicci, albeit qualifying it as a shop product with a date around 1410.7 Federico Zeri listed the panel as school or shop of Bicci di Lorenzo.8 The image was also assigned to Bicci’s workshop, but with a date around 1440, by Carl Strehlke, in his unpublished checklist of Italian paintings at Yale.

Notwithstanding the present condition of the panel, which has to some degree influenced the evaluation of it, there is little question that the Crucifixion conforms in most aspects to the stylistic and compositional models formulated in Bicci di Lorenzo’s workshop. The detail of Christ on the Cross surrounded by flying angels gathering His blood is consistent with other such representations by the artist conceived for large altarpieces, such as that in a tondo fragment formerly in the Viezzoli collection, Genoa, which is distinguished by the same folds in Christ’s loincloth and a similar, irregular tooling in His halo.9 Exact comparisons for the figures of the saints in the Yale Crucifixion are found, instead, in a little-known fresco cycle executed by Bicci and his workshop for the Magdalen Chapel in the Augustinian church of Santo Stefano in Empoli. The bust-length patriarchs and prophets painted in quatrefoils along the large entrance arch to that chapel bear a striking likeness to the male figures in the present work. The Yale Saint Elijah, for instance, virtually replicates the bearded image of Abraham holding an identically unfurled scroll in the fresco (fig. 2), while Tobias strongly recalls the image of the beardless young prophet Joshua (fig. 3). The losses of the paint surface in the Yale Saint Albert, moreover, reveal the same hasty drawing technique and cursory treatment of individual features that is discernible in other figures along the more worn sections of the frescoed archway.

Although the relationship of the Magdalen Chapel frescoes to Bicci’s production has never been questioned by scholars, their dating, and the extent of the artist’s direct involvement in their execution, have been the subject of divergent opinions. Following restorations in 1992, Cecilia Frosinini attributed the entire cycle to Stefano d’Antonio di Vanni (1405–1483), suggesting that he took over the commission from Bicci after the end of their joint partnership in 1434.10 Rosanna Caterina Proto Pisani, on the other hand, viewed the frescoes as a collaborative effort between Bicci and Stefano d’Antonio—whom she, too, considered responsible for the figures of patriarchs and prophets—and proposed a date between 1425 and 1430.11 More recently, however, Silvia De Luca has strongly reiterated the attribution to Bicci, noting that “all of the paintings bear the unmistakable mark of Bicci di Lorenzo.”12 For De Luca, the stylistic inconsistencies between the various zones of the fresco are not so great as to warrant a division of hands, other than what typically existed between the head of a workshop and his various assistants. The same author proposed a significantly earlier chronology and dated the cycle not long after 1423, when Bicci was entrusted with the execution of a triptych for the chapel of Simone Guiducci in the Collegiata of Sant’Andrea in Empoli, now in the Museo della Collegiata—the first of several commissions awarded to the artist’s workshop in and around the city over the course of two decades. Bicci’s full responsibility for the execution of the Magdalen Chapel fresco cycle was subsequently reiterated by Francesco Suppa, who nevertheless returned to Proto Pisani’s dating in the second half of the 1420s.13

The stylistic homogeneity between the Yale panel and the Magdalen Chapel frescoes suggests a virtually contemporary date of execution. The sturdily built types with rounded proportions that inhabit both works, however, share little of the refined Late Gothic mannerisms of the 1423 Collegiata triptych and recall Bicci’s more mature efforts from the beginning of the fourth decade, as represented by the dated 1430 Vertine Triptych (fig. 4) and by the polyptych in San Niccolò in Cafaggio, completed in 1433. A chronology for the Yale panel and the Magdalen Chapel frescoes in greater proximity to these images seems therefore more plausible. Notwithstanding efforts to discern the hand of Stefano d’Antonio in the artist’s production from this period, the Yale Crucifixion, like the Magdalen Chapel prophets, reveals above all a close adherence to Bicci’s prototypes, even if rendered with a pronouncedly looser brushstroke and less polished finish. These elements suggest the intervention of an assistant in Bicci’s workshop, executing the master’s designs, rather than an independent personality.

The allusions to the past and present history of the Carmelite order implicit in the iconography the Yale Crucifixion suggest that the work may have been intended for a prominent cleric or other figure closely affiliated with a Carmelite convent. The symbolic significance of the old and new habit, reflected in this instance by the visual juxtaposition of Elijah and Albert of Trapani, was highlighted by the monumental altarpiece painted by Pietro Lorenzetti in 1329 for the monks of Santa Maria del Carmine in Siena.14 Conceived as a manifesto of the Carmelite order, the Lorenzetti altarpiece shows the mythical founders, Elijah and Elisha, in the main panels, dressed anachronistically in the new white mantle. The predella, which illustrates in vivid detail the history of the order from the legendary events of its foundation to the present, traces the transition from the pallium barratum worn by the ancient monks in the Carmelites at the Fountain of Elijah and the Carmelites Receiving the Rule by Albert of Vercelli to the white cloak held up by the pope in the Approval of the Carmelite Habit by Honorius IV. Although usually confined to narrative scenes, the representation of the ancient Carmelite habit continued to have political and spiritual connotations for the order’s identity well into the fifteenth century.15 Filippo Lippi included monks wearing the pallium barratum alongside monks in contemporary dress in a fresco fragment from the cloister of Santa Maria del Carmine in Florence, showing the Confirmation of the Carmelite Rule—a work possibly painted around the same time as the Yale Crucifixion.16 Much like Pietro Lorenzetti’s predella, the fresco has been interpreted as a visual celebration and reminder of the “historic passage” of the Carmelites from their Eastern roots as hermits on Mount Carmel to their existence as a conventual order legitimized by the pope in the West.17 Albeit on a more intimate scale, the Yale Crucifixion seems to allude to a similar concept, which was reiterated in the order’s texts and was presumably embedded in the consciousness of every monk in the order. Considering Bicci di Lorenzo’s personal ties to the Florentine monastery of Santa Maria del Carmine and his membership in the famous Compagnia di Sant’Agnese, which had its headquarters in the church, it is worth speculating whether the artist was entrusted with the commission by an erudite member of that community.18 Perhaps even more pertinent, the patron of the Yale Crucifixion might be sought among the spiritual leaders of the Carmelite hermitage of Santa Maria delle Selve in Lastra a Signa, in the hills outside Florence. Founded in 1413, the convent was the highly regarded center of the Carmelite Observant movement in Tuscany. At the core of its constitutions was the revival of certain features of the “primitive” Carmelite Rule, with its emphasis on prayer, stricter enclosure, and silence.19 The figure of the penitent Magdalen and the exhortative nature of the verses inscribed on Elijah’s scroll, emphasizing the meditative quality of the image, would have been especially appropriate in such a context. It may be more than mere coincidence that the prior and then superior of Le Selve around the time of execution of the Yale Crucifixion was the famous Carmelite preacher and doctor of theology Fra Angelo Mazzinghi, later beatified by the order—whose name could be alluded to by the Archangel Raphael.20 —PP

Published References

H[amilton], G[eorge] H[eard]. “The Hunt Gift.” Bulletin of the Associates in Fine Arts at Yale University 8, no. 2 (February 1938): 51–53., 52; Seymour, Charles, Jr. Early Italian Paintings in the Yale University Art Gallery. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1970., 24, 305, no. 8; Fredericksen, Burton B., and Federico Zeri. Census of Pre-Nineteenth-Century Italian Paintings in North American Public Collections. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1972., 29, 600

Notes

-

On the various connotations of the image of Raphael and Tobias, see, most recently, Argenziano, Raffaele. “I compagni di Viaggio Tobia e Raffaele: Alcune precisazioni sull’iconografia di Raffaele ‘Archangelo’ come protettore e taumaturgo.” In Angelos—Angelus: From Antiquity to the Middle Ages, ed. Agostino Paravicini Bagliani, 463–83. Micrologus: Nature, Sciences, and Medieval Societies 23. Florence: Sismel, 2015., 463–83. ↩︎

-

According to patristic texts, at the time of Elijah’s birth, his father dreamed of “men dressed in white clothes” who wrapped the infant in fire and gave him fire to eat; cited in Cannon, Joanna. “Pietro Lorenzetti and the History of the Carmelite Order.” Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 50 (1987): 18–28., 25. ↩︎

-

For an image of Saint Albert of Trapani, see Lippo d’Andrea, Virgin and Child Enthroned between Saints Albert of Trapani and Peter and Saints Paul and Anthony Abbot; The Annunciation. ↩︎

-

Usually, Saint Ursula is shown as a princess martyr, wearing a crown and/or carrying a flag. The present depiction follows the iconography of the saint in Bicci di Lorenzo’s triptych in the church of Sant’Ambrogio, Florence, where her image is identified by an inscription below it. Although it could be argued that Saint Cristina of Bolsena is also represented as a young virgin martyr holding a book and an arrow in Sano di Pietro’s altarpiece for the basilica dedicated to her in Bolsena, the cult of Saint Cristina was not particularly strong outside Bolsena and the Lazio region, and she appears only rarely in Tuscan altarpieces. ↩︎

-

H[amilton], G[eorge] H[eard]. “The Hunt Gift.” Bulletin of the Associates in Fine Arts at Yale University 8, no. 2 (February 1938): 51–53., 52. ↩︎

-

Richard Offner, July 7, 1938, curatorial files, Department of European Art, Yale University Art Gallery. ↩︎

-

Seymour, Charles, Jr. Early Italian Paintings in the Yale University Art Gallery. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1970., 24, no. 8. ↩︎

-

Federico Zeri, in Fredericksen, Burton B., and Federico Zeri. Census of Pre-Nineteenth-Century Italian Paintings in North American Public Collections. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1972., 29, 600. ↩︎

-

The tondo was attributed to Bicci by Federico Zeri and Everett Fahy, whose opinions are recorded in the Fototeca Zeri, Federico Zeri Foundation, Bologna, inv. no. 4710. ↩︎

-

Frosinini, Cecilia. “Stefano d’Antonio di Vanni a Empoli.” Antichità viva 31, no. 1 (January–February 1992): 5–12., 9. ↩︎

-

Caterina Proto Pisani, Rosanna. “La chiesa di Santo Stefano degli Agostiniani a Empoli: Cronaca dei restauri per un nuovo museo.” Antichità viva 31, no. 1 (January–February 1992): 13–22., 21. ↩︎

-

“Tutti i dipinti mostrano l’impronta inconfondibile di Bicci di Lorenzo”; see De Luca, Silvia. “Da Giovanni Pisano a Lorenzo Monaco: Percorsi dell’arte medievale a Empoli.” In Empoli: Nove secoli di storia. Vol. 1, Età medieval, Età moderna, ed. Giuliano Pinto, Gaetano Greco, and Simonetta Soldani, 137–62. Rome: Edizioni di Storia e Letteratura, 2019., 153. ↩︎

-

Suppa, Francesco. “Bicci di Lorenzo nel transetto destro: Un’aggiunta al catalogo empolese del pittore.” In Tracce di devozione: Sinopie e affreschi in Santo Stefano a Empoli, ed. Cristina Gelli, 36–51. Florence: Polistampa, 2022., 41–42. ↩︎

-

The main panels of this altarpiece and the predella are now in the Pinacoteca Nazionale, Siena (inv. nos. 16a–b, 62, 64, 83–84, 578–579); see Torriti, Piero. La Pinacoteca Nazionale di Siena. Vol. 1, I dipinti dal XII al XV secolo. Genoa: Sagep, 1977., 97–103. For an exhaustive discussion of its iconography, see Cannon, Joanna. “Pietro Lorenzetti and the History of the Carmelite Order.” Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 50 (1987): 18–28., 18–28; and Gardner von Teuffel, Christa. “The Carmelite Altarpiece (circa 1290–1550): The Self-Identification of an Order.” Mitteilungen des Kunsthistorischen Institutes in Florenz 57, no. 1 (January 2015): 3–42., 16–18. ↩︎

-

For a summary of all the issues surrounding the Carmelite habit, see Jotischky 2002, 45–78. ↩︎

-

Holmes, Megan. Fra Filippo Lippi: The Carmelite Painter. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1999., 69–79. Megan Holmes places the frescoes in the early part of Lippo’s career (ca. 1430–34). ↩︎

-

Holmes, Megan. Fra Filippo Lippi: The Carmelite Painter. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1999., 77. See also Holmes, Megan. “The Carmelites of Santa Maria del Carmine and the Currency of Miracles.” In The Brancacci Chapel: Form, Function and Setting, ed. Nicholas Eckstein, 157–75. Florence: Leo S. Olschki, 2007., 163–64, where the author notes that “in the Lorenzetti predella the striped mantle asserts a certain kind of historical facticity within a panoramic presentation of the phases of the transformation as the Carmelites change from an eremitical brotherhood on the slopes of Mount Carmel in the Holy Land to a cenobitical and mendicant monastic order in the West.” ↩︎

-

The record books of the Compagnia di Sant’Agnese list Bicci as paying his membership dues along with his son, Neri di Bicci, in 1430. Both Bicci and his wife, Benedetta, were buried in the Carmine. See Eckstein, Nicholas A. The District of the Green Dragon: Neighborhood Life and Social Change in Renaissance Florence. Florence: Leo S. Olschki, 1995., 48; and Holmes, Megan. Fra Filippo Lippi: The Carmelite Painter. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1999., 248n78. ↩︎

-

Holmes, Megan. Fra Filippo Lippi: The Carmelite Painter. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1999., 54. For more on Santa Maria delle Selve, see Lippo di Andrea’s altarpiece for that community: Yale University Art Gallery, inv. no. 1959.15.1a–c, https://artgallery.yale.edu/collections/objects/43494. ↩︎

-

Fra Angelo Mazzinghi was prior at Le Selve from 1419 to 1430 and once again in 1437. Between 1435 and 1437, he served as prior of Santa Maria del Carmine. Like Bicci di Lorenzo, he was a member of the Compagnia di Sant’Agnese in Santa Maria del Carmine, where he is listed as registered in 1431. See Pratti, Pierantonio. “Mazzinghi, Angelo.” In Dizionario biografico degli italiani. Rome: Istituto della Enciclopedia Italiana, 2008. https://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/angelo-mazzinghi_(Dizionario-Biografico)/.. Mazzinghi’s obituary in the Necrologium of Santa Maria del Carmine described him in the following terms: “A venerable man of the greatest virtue and excellent doctrine, a teacher of judgment, achieving great fame and holiness in his life, and a most famous preacher, who was the first son at the inception of the Observance at Le Selve”; cited by Holmes, Megan. Fra Filippo Lippi: The Carmelite Painter. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1999., 54. Holmes noted that he was one of the few friars in Florentine Carmelite circles with a patrician, and therefore privileged, economic background. ↩︎