James Jackson Jarves (1818–1888), Florence, by 1859

The panel, of a horizontal grain, retains its original thickness of 2.5 centimeters and has been slightly beveled along the back right edge. An insert of old wood, 2.5 by 3 centimeters, fills a notch cut into the lower corner on that side. Eight hand-cut but probably modern nails protrude on a diagonal along the left, top, and bottom margins on the obverse of the panel. Undoubtedly intended to secure a later frame, none of these has provoked iron staining in the wood. The margins of the panel outside the picture field have been scraped back to the wood along the top, right, and bottom edges, whereas a linen underlayer survives along the left edge. Pastiglia moldings defining a quatrefoil shape for the picture field have been scraped down to the plane of the gesso preparation of the full panel; traces of bolus, silver, and gold leaf survive in the lower-right corner only. The paint surface is generally well preserved, with minimal abrasion, though the continuity of the image is interrupted by small nicks scattered throughout. Larger losses occur in the trees and stream at lower right, and one major loss occurs in the trees at upper right.

This painting is a fragment of a predella from an unidentified altarpiece. Already restored when it was in the James Jackson Jarves collection (fig. 1), it suffered considerable losses in a 1965 cleaning. Those areas in which the original painted surface is still intact, however, permit a fair assessment of its original appearance and palette. When it entered Yale’s collection, the painting bore Jarves’s attribution, reiterated by Russell Sturgis, to the school of Taddeo Gaddi.1 In 1916 Osvald Sirén catalogued it as “Manner of Andrea di Giusto,” observing that its inferior quality and generic characteristics prevented a precise attribution to any known master but that “certain peculiarities in the treatment of the wavy draperies and the oblique types” pointed to Andrea di Giusto.2 Uncertainties regarding its authorship were reflected in later assessments as well. Richard Offner ascribed it to an anonymous Florentine master working around 1450 under the influence of Masaccio and Fra Angelico, whereas Charles Seymour, Jr., echoed Sirén’s opinion and labeled it “Florentine School (manner of Andrea di Giusto),” with a date around 1435.3 Federico Zeri was the first author to suggest the name of a specific artist when he assigned the picture to Bicci di Lorenzo’s partner, Stefano d’Antonio di Vanni (1405–1483), who is first documented in Bicci’s workshop in 1420 and was involved in a compagnia with the older painter between 1426 and 1434.4 According to Zeri, the Agony in the Garden was executed by Stefano d’Antonio “under Bicci’s direction” around 1430, the same period during which the two artists collaborated on the Annunciation in the Walters Art Museum, Baltimore (fig. 2). Subsequent scholarship unanimously embraced Zeri’s argument, listing the Yale panel among a small group of narrative predella scenes purportedly executed by Stefano at the time his partnership with Bicci.

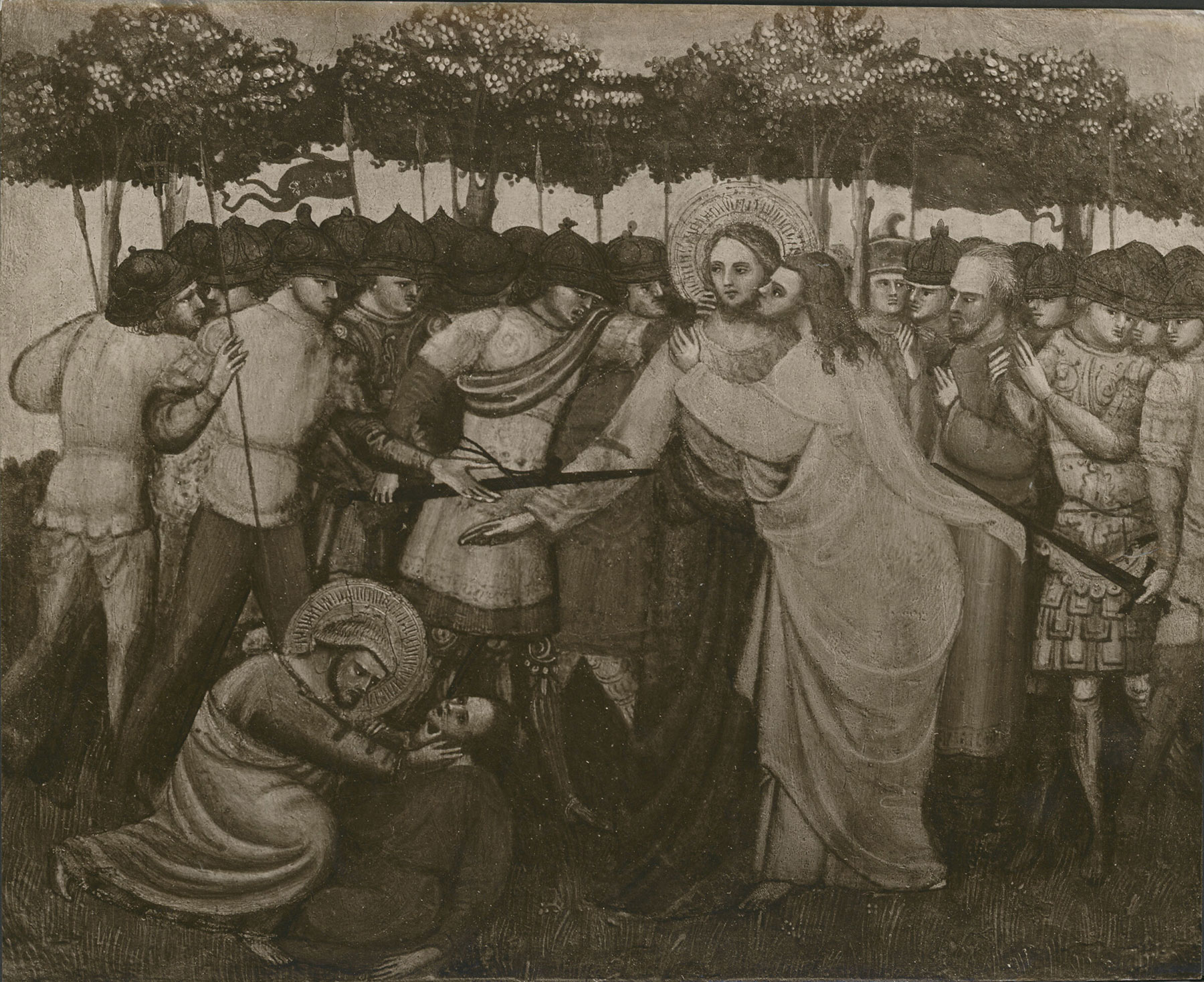

In the most recent discussion of the Yale Agony in the Garden, Andrea Staderini, who reiterated the attribution to Stefano d’Antonio, convincingly associated it with the same predella as a Descent from the Cross in the Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, D.C. (fig. 3), and with a previously unpublished Betrayal of Christ formerly in the Artaud de Montor collection, Paris (fig. 4).5 The Smithsonian fragment, catalogued by early authors as a possible work of Allegretto Nuzi, was given to Stefano d’Antonio by Zeri,6 whereas the ex-Artaud de Montor panel, known only from a photograph in the Berenson Library, Villa I Tatti, Settignano, was labeled by Bernard Berenson as “Bicci di Lorenzo.”7 To Staderini’s reconstruction may be added a fourth predella scene, with the Resurrection. It, too, is known only from a photograph at Villa I Tatti (fig. 5), where it was tentatively filed by Berenson under Giovanni del Biondo and Giovanni Bonsi.8 That all four images are the product of the same hand is confirmed by their shared formal vocabulary and topographical details, as well as by the identical tooling in the haloes. Still visible beneath the repaints along the sides of the Smithsonian panel, moreover, is evidence of the same quatrefoil shape that came to light in the cleaning of the Yale picture, a detail that all but confirms their physical relationship.9

Less persuasive is the proposed link between the reconstructed predella and the production hitherto assembled under the name of Stefano d’Antonio. Notwithstanding the precarious condition of some of the panels, comparisons between them and the scenes below Bicci’s Walters Annunciation and below the Saint Lawrence in the Galleria dell’Accademia, Florence (fig. 6)—currently assigned to Stefano d’Antonio by most authors10—reveal significant discrepancies in handling and execution. Both the Walters and Accademia predellas translate Bicci’s Late Gothic prototypes into vivacious, preciously handled figures rendered in miniaturistic detail that have little in common with the stolid, prosaically depicted bystanders in the Smithsonian Descent from the Cross (see fig. 3), in particular. Moreover, absent from the Yale Agony in the Garden are the sensitively applied atmospheric effects that characterize the Walters and Accademia settings. Finally, certain eccentricities of style reflected in the ex-Artaud de Montor panel (see fig. 4), such as the awkward pose of Judas or the ferocious expression of the sword-wielding soldier behind Christ, seem incompatible with anything produced in Bicci’s workshop and oriented toward different models.

A hitherto overlooked but significant factor in the evaluation of the Yale Agony in the Garden is the quatrefoil shape of the picture field, which appears anachronistic in a work purportedly executed around 1430. The essentially Gothic format was revived in Lorenzo Ghiberti’s first Baptistery doors, completed in 1424, but was adopted in only a handful of fifteenth-century altarpiece designs produced in Lorenzo Monaco’s shop over the course of little more than a decade, from the Agony in the Garden in the Galleria dell’Accademia, Florence,11 painted around 1400, to the 1414 Coronation of the Virgin in the Gallerie degli Uffizi, Florence (fig. 7). After this date, the quatrefoil design also disappears from Lorenzo Monaco’s oeuvre, replaced by the more modern, rectangular compositions favored by other Florentine painters. While such evidence is not conclusive, it does seem to confirm a more precocious chronology for the Yale panel and its related fragments. The identity of their author is elusive, but stylistic as well as physical evidence suggests the hand of a minor personality responding to different trends in Florentine painting in the early 1420s, before the death of Lorenzo Monaco.

Based on the four surviving scenes, it may be postulated that the dismembered predella from which they were excised was dedicated to Christ’s Passion. A hitherto unidentified Crucifixion probably stood in the center, flanked on the left by the Yale Agony in the Garden and the ex-Artaud de Montor Betrayal of Christ (see fig. 4) and on the right by the Smithsonian Descent from the Cross (see fig. 3), followed by the Resurrection (see fig. 5). It is also not out of the question that the three panels, and maybe additional episodes of the Passion, originally stood below an image of the Crucified Christ or even a sculpted cross, as in Niccolò di Pietro Gerini’s monumental complex for the Compagnia del Crocifisso in the Collegiata of Sant’Andrea in Empoli.12 The identification of the three mysterious bystanders at right in the Smithsonian Descent from the Cross could potentially provide a clue to the patronage of the lost altarpiece. Two of the figures carry large jars of ointment. One is a pope, identified by the papal tiara with three gold crowns; he wears a white tunic under what was originally a blue mantle (now oxidized to black). The long-haired bearded figure next to him, wearing a red cloak with an ermine collar, is perhaps a nobleman or prince. Behind them is a young man dressed in a red tunic and green cloak. The focus on the ointment jars that the first two figures hold can perhaps be viewed in terms of the resonance that such objects held in the medieval imagination and their association, through the Magdalen’s anointing of Christ, with the virtues of charity and faith.13 —PP

Published References

Jarves, James Jackson. Descriptive Catalogue of “Old Masters” Collected by James J. Jarves to Illustrate the History of Painting from A.D. 1200 to the Best Periods of Italian Art. Cambridge, Mass.: H. O. Houghton, 1860., 45, no. 29; Sturgis, Russell, Jr. Manual of the Jarves Collection of Early Italian Pictures. New Haven: Yale College, 1868., 38, no. 29; W. F. Brown, Boston. Catalogue of the Jarves Collection of Early Italian Pictures. Sale cat. November 9, 1871., 16, no. 29; Sirén, Osvald. A Descriptive Catalogue of the Pictures in the Jarves Collection Belonging to Yale University. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1916., 81, no. 32; Seymour, Charles, Jr. Early Italian Paintings in the Yale University Art Gallery. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1970., 130–31, 313, no. 88; Fredericksen, Burton B., and Federico Zeri. Census of Pre-Nineteenth-Century Italian Paintings in North American Public Collections. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1972., 192, 599; Zeri, Federico. Italian Paintings in the Walters Art Gallery. 2 vols. Baltimore: Walters Art Gallery, 1976., 1:33; Padoa Rizzo, Anna, and Cecilia Frosinini. “Stefano d’Antonio di Vanni (1405–1483): Opere e documenti.” Antichità viva 23, nos. 4–5 (1984): 5–33., 8, fig. 4; Staderini, Andrea. “‘Primitivi’ fiorentini dalla collezione Artaud de Montor: Parte I, Lippo d’Andrea e Stefano d’Antonio.” Arte cristiana 92, no. 823 (2004): 259–66., 264, 266n29, fig. 7; Parenti, Daniela. “Stefano di Antonio di Vanni.” In Dizionario biografico degli italiani. Rome: Istituto della Enciclopedia Italiana, 2019.

Notes

-

Jarves, James Jackson. Descriptive Catalogue of “Old Masters” Collected by James J. Jarves to Illustrate the History of Painting from A.D. 1200 to the Best Periods of Italian Art. Cambridge, Mass.: H. O. Houghton, 1860., 45, no. 29; and Sturgis, Russell, Jr. Manual of the Jarves Collection of Early Italian Pictures. New Haven: Yale College, 1868., 38. ↩︎

-

Sirén, Osvald. A Descriptive Catalogue of the Pictures in the Jarves Collection Belonging to Yale University. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1916., 81, no. 32. ↩︎

-

Richard Offner, verbal opinion, 1927, recorded in the Frick Art Reference Library, New York; and Seymour, Charles, Jr. Early Italian Paintings in the Yale University Art Gallery. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1970., 130–31, no. 88. ↩︎

-

Federico Zeri, in Fredericksen, Burton B., and Federico Zeri. Census of Pre-Nineteenth-Century Italian Paintings in North American Public Collections. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1972., 192, 599; and Zeri, Federico. Italian Paintings in the Walters Art Gallery. 2 vols. Baltimore: Walters Art Gallery, 1976., 1:33. ↩︎

-

Staderini, Andrea. “‘Primitivi’ fiorentini dalla collezione Artaud de Montor: Parte I, Lippo d’Andrea e Stefano d’Antonio.” Arte cristiana 92, no. 823 (2004): 259–66., 262. ↩︎

-

Federico Zeri, in Fredericksen, Burton B., and Federico Zeri. Census of Pre-Nineteenth-Century Italian Paintings in North American Public Collections. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1972., 192, 648. The painting was among the works donated to the Smithsonian Institution in 1929 by John Gellatly (1853–1931); see Catalogue of American and European Paintings in the Gellatly Collection. Washington, D.C.: National Collection of Fine Arts, 1933., 13, no. 8. ↩︎

-

A handwritten note by Berenson on the back of the photograph states that the painting was last recorded in the collection of Erwin Rosenthal, Munich. On this work, see Artaud de Montor, A. F. Peintres primitifs: Collection de tableaux apportée de l’Italie e publiée par M. le chevalier Artaud de Montor. Paris: Challamel, 1843., 38, no. 71 (as Pietro Lorenzetti); and Staderini, Andrea. “‘Primitivi’ fiorentini dalla collezione Artaud de Montor: Parte I, Lippo d’Andrea e Stefano d’Antonio.” Arte cristiana 92, no. 823 (2004): 259–66., 262. ↩︎

-

A handwritten note by Berenson on the verso for the photograph reads “with Giovanni del Biondo. Giovanni Bonsi?” The only indication of the painting’s location is “Roma.” The present author is very grateful to Christopher Daly for directing her to this image. ↩︎

-

The panels do not share exactly the same measurements, but it is clear that the Smithsonian Descent from the Cross, like the Yale picture, was cut on all sides. Its present dimensions are 25.4 by 33 centimeters. The dimensions of the Betrayal of Christ were given by Artaud de Montor as 30.8 by 35.2 centimeters. Judging from the black-and-white photograph in the Berenson Library (see fig. 4), the picture was in a similar state as the Yale and Smithsonian fragments and had a new gold ground applied over the original pigment in the sky. ↩︎

-

Despite documentary evidence, effort to isolate Stefano’s contribution in works produced under the banner of Bicci’s compagnia are not always conclusive. Walter Cohn’s initial distinction of hands in the San Niccolò in Cafaggio Polyptych (see Cohn, Werner. “Maestri sconosciuti del quattrocento fiorentino, II—Stefano d’Antonio.” Bollettino d’arte 44, no. 1 (January–March 1959): 61–68., 61–68), for which both artists received payment in 1434, has not been acknowledged by more recent scholarship; see Chiodo, Sonia. “Osservazioni su due polittici di Bicci di Lorenzo.” Arte cristiana 88, no. 799 (July–August 2000): 269–80., 274. ↩︎

-

Inv. no. 1890 no. 438. ↩︎

-

For a reconstruction of this complex, now in the Museo della Collegiata, Empoli, see De Luca, Silvia. “Da Giovanni Pisano a Lorenzo Monaco: Percorsi dell’arte medievale a Empoli.” In Empoli: Nove secoli di storia. Vol. 1, Età medieval, Età moderna, ed. Giuliano Pinto, Gaetano Greco, and Simonetta Soldani, 137–62. Rome: Edizioni di Storia e Letteratura, 2019., 144–47, pl. 16. The three Passion episodes in its predella are a Last Supper, Capture of Christ, and Lamentation. ↩︎

-

See Barbashina, Violetta. “‘ . . . In Charity, for the Sake of Charity, and with Charity’: The Ointment Jar and the Virtue of Caritas in the Apothecary’s Practice.” History of Pharmacy and Pharmaceuticals 64, no. 1 (2022): 5–28., 5–28, esp. 22–23. A bearded lay figure wearing an ermine cloak and holding a large jar of ointment appears behind the kneeling Magdalen in Gerini’s predella scene with the Lamentation in the Museo della Collegiata, Empoli. It may be hypothesized that, in this instance, he represents one of the wealthy members of the lay confraternity that sponsored that altarpiece. ↩︎