Maitland Fuller Griggs (1872–1943), New York, by June 1926

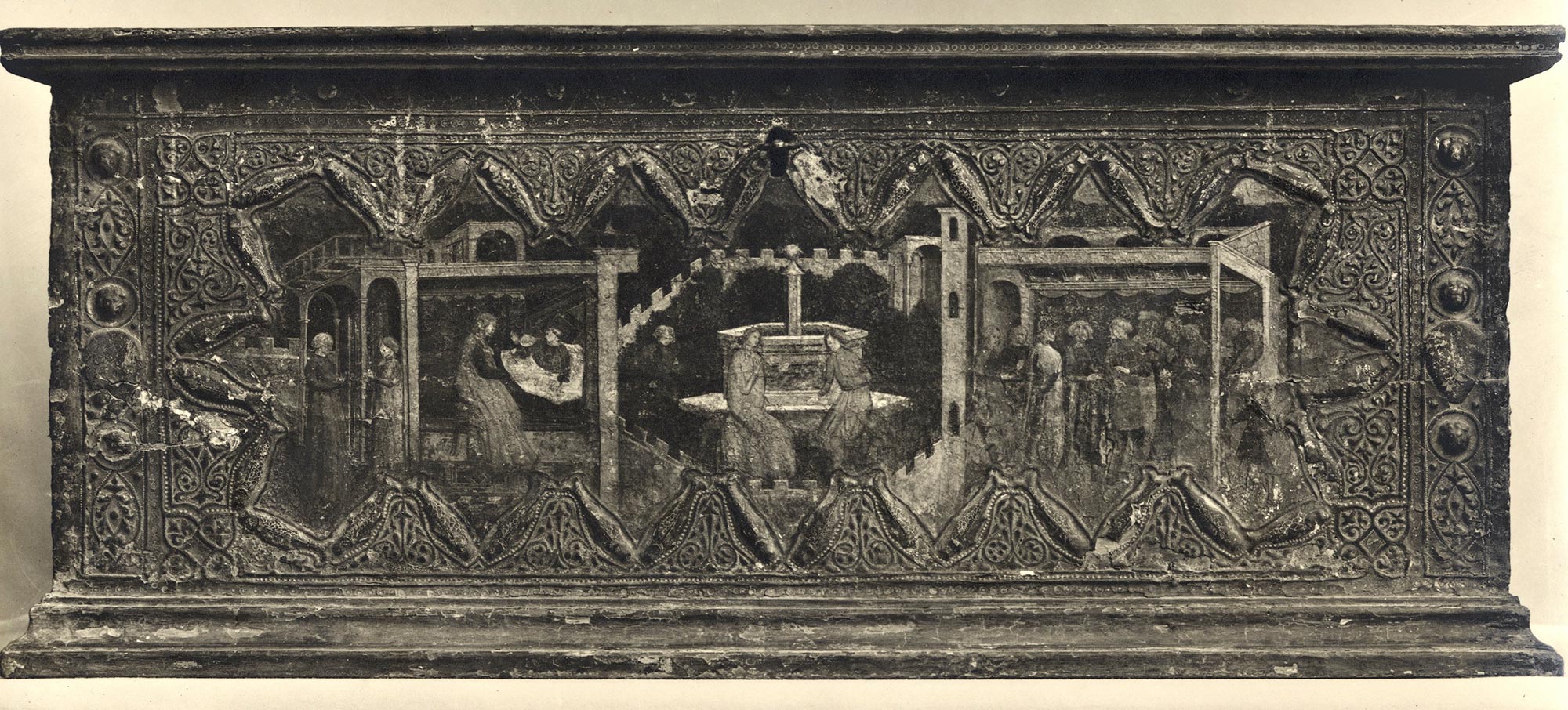

The panel, of a horizontal wood grain, has been thinned to a depth of 1 centimeter and cradled, presumably by 1926, before Maitland Griggs acquired it. Two labels are preserved on the cradle, reading “11 B. Gozzoli” and “Giovanni di Paolo / 1403–1482, No. 15,401.” The cradle has provoked several long horizontal splits in the panel, notably at 13 and 20 centimeters from the bottom at the left and at 6.5 and 22.5 centimeters from the bottom at the right. There is no trace of a keyhole or of the removal of a lock hasp anywhere on the panel. A number of deep gouges and smaller knicks, especially near the center of the composition and among the figures occupying the building at the left, appear to be due to the hazards of rough usage typical of decorated furniture chests. Other broad areas of total loss and exposed gesso are the result of overzealous cleaning; these are concentrated in the landscape background at the center and at the right—where areas of deep blue between the top lines of the tents have been systematically removed—but are also scattered throughout the draperies and armor across the entire picture surface. The building at the left and tents at the right are abraded but remain much better preserved than the rest of the painting. In addition to having suffered from solvent damage and abrasion, every figure has been “canceled” by at least one long vertical or diagonal scratch. The middle horseman and the attendant in a yellow doublet beneath him have been more aggressively vandalized. A synthetic varnish, applied during a cleaning of 1965–66, has grayed, further dulling the pictorial effect of the image.

Identifying the subject of this cassone panel has occupied scholars, with little agreement, since it was first published by Paul Schubring as illustrating the story of the four sons shooting at their father’s corpse, as narrated in chapter 45 of the Gesta Romanorum.1 The only point in common shared by that story and this image, however, is the number of the protagonists. No other detail—above all, that three of the brothers in the text hated the fourth or that in the painting no one carries a bow and two living monarchs are portrayed—coincides even obliquely. Charles Seymour, Jr., in his one-sentence catalogue entry for the painting, retained Schubring’s title for it but claimed that it derived from Boccaccio.2 Paul Watson tentatively suggested that the story of the three daughters of N’Arnald Civada of Marseille by Boccaccio (Decameron 4.3) might be the actual source of the image, but that story involves three female and three male protagonists, none of whom wear armor at any point, again in contradiction to the painted imagery here.3 Ellen Callmann correctly rejected this identification but inexplicably defended Schubring’s contention that the Gesta Romanorum was the literary source for this scene.4 Instead, it is almost certainly based on the twelfth-century French chivalric romance Quatre fils Aymon, the most popular, judging from the number of printed editions issued in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, of the chansons de geste circulating in late medieval Europe.

The numerous surviving manuscripts of Quatre fils Aymon differ from each other in important details. The Yale painting seems to draw its imagery less from the French originals than from one or more of the Italian translations of this story. Fourteenth-century Tuscan manuscripts, titled Rinaldo da Montalbano after its chief protagonist, the eldest of the four sons of Aymon of Dordone, add characters and episodes not found in the French versions of the story.5 At the left, the four sons of Aymon (Amone in Italian) kneel before the Emperor Charlemagne and his barons. In the French texts, they are presented to the emperor by their father at a tournament in Paris convened at the Feast of Pentecost, and it is possible that the older bearded figure standing to the left of the imperial throne is meant to portray Amone. It is equally possible, however, that this figure is a counselor of the emperor; in the Italian texts, the brothers do not appear together with their father, having been sent to Paris by their mother, Clarice di Soave, to be invested as knights by Charlemagne. The emperor acceded to this request but also banished the brothers for having killed their father’s enemy, Ghinamo di Bajona, duke of Maganza, who had five years earlier betrayed their father with false accusations of the infidelity of his wife and illegitimacy of his sons. Charlemagne tasked the brothers with a pilgrimage to the Holy Land as penance to expiate the ban of exile. In the center of the Yale panel, the four young men, invested as knights and clad in full armor, leave Charlemagne’s castle on horseback, bound for Jerusalem. One, presumably Rinaldo, receives a parting gift from, or exchanges a pledge with, a courtier dressed in green with red leggings standing on the threshold of the palace, possibly the paladin Orlando (Roland in French), a confidante of the emperor and in some versions of the story said to be a cousin of the brothers. Returning first to their mother’s castle, the brothers encounter the magician Malagigi (Maugis d’Aigremont)—also, although unbeknownst to them, a cousin—disguised as an old woman: this may be the partially legible figure in a hooded red cloak visible at the center of the Yale panel. Malagigi presents Rinaldo with the magic horse, Baiardo (Bayard), and sword, Frusberto (Froberge), that he, in turn, had received from Thetis, the mother of Achilles. In the French versions of the story, the four brothers ride together on Bayard. In Italian texts, each brother is presented with his own horse and arms.

After several further adventures, the brothers took ship and arrived at the frontiers of Persia, where they found the city of Nilibi on the river Fosca and its king, Amostante, besieged by the Persian sultan. The brothers first presented themselves to the sultan and offered him their services, requesting payment for one hundred knights. The sultan refused, saying that not even the famous Orlando was worth that sum, but he granted the brothers permission to enter the city under siege. This, presumably, is the scene portrayed at the right of the Yale predella, although no aspect of costume or heraldry makes such an identification a certainty. Callmann suggested that the standard flown above the sultan’s tent bears the imperial eagle, but the device here is not the two-headed eagle of the Holy Roman Empire.6 She further suggested that the four soldiers lounging among the tents in the middle distance are the four sons, but these soldiers are not in armor and are more likely emblematic indicators that the sultan was holding Nilibi under siege with a large army. In subsequent verses of the story, Rinaldo was made captain within the walls of Nilibi and shortly afterward led the citizens in battle, defeating the sultan and his troops.

Although its exceptional quality is still evident through its indifferent state of preservation, the Yale panel has elicited very little notice in the sporadic literature concerned with early Florentine cassone painting. Aside from generic references to the Florentine school of the late fourteenth century7 or early fifteenth century,8 and a cannily perceptive remark of Richard Offner, who in 1927 observed affinities with the style of Paolo Uccello,9 only one focused attribution has been brought forward for the panel. Everett Fahy included it among a group of paintings, chiefly cassone panels and deschi da parto (see Florentine School(?), Desco da Parto), which he assembled around a painted chest in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.10 Fahy named the artist he believed to be responsible for these works the “Master of Charles III of Durazzo,” after the subject of the painted front of the Metropolitan Museum chest, the capture of Naples by Charles III of Durazzo in 1381. He created a list of some forty paintings by amalgamating newly discovered works to others formerly referred to by a variety of names, including Master of the Siege of Taranto or Master of Ladislaus of Durazzo, following earlier (mistaken) identifications of the subject of the Metropolitan cassone, or Master of Cracow, after one of the other cassone panels in the group.11 This number would be considerably expanded if his suggestion is accepted that the artist was also responsible for the body of works conventionally labeled as by the Master of San Martino a Mensola.12

Despite Miklós Boskovits’s contention that this large group of paintings is “substantially homogeneous even if individual works have been radically altered by restorations,”13 the primary factor common to most of them is their format. A majority of the cassone panels are distinguished not by a homogeneous painting style but by their exuberant pastiglia or gilt gesso ornamental surrounds, often assuming fanciful geometric shapes that subsume the painted narrative scenes. Some, like the name piece of the group in New York, employ a pastiglia rope device to divide the narrative into three discreet, roughly circular scenes, each of which is highly decorative and complex but little more than artisanal in pictorial ambition. Others, like the well-preserved cassone in the Bargello representing episodes from Boccaccio’s story of Saladin and Messer Torrello, adopt the same framing device but employ a sophisticated figural vocabulary with a wide expressive range while evincing little interest in spatial devices or compositional variety.14 Still others with even more inventive framing systems are merely mechanical in their painting style. While it may be reasonable to argue that the complexity and sophistication of their manufacture implies a single proficient and prolific workshop, that shop must have employed a stable of painters of varying degrees of professional competence. The label “Master of Charles III of Durazzo,” therefore, actually denotes a category of object rather than a single artistic personality in any conventional sense.

A small number of the cassone panels in the Master of Charles III of Durazzo group feature a unified, rectangular picture field, the pastiglia framing decoration restricted to the rectilinear periphery of the front panel of the chest. These are generally explained as the latest of the paintings in the group, the closest to ca. 1420 within a range that may begin as early as 1380.15 While it is possible that dating alone may be adequate to explain the differences in appearance among some of these, it is not a sufficient explanation for the differences presented by the Yale panel to all the other members of the group. Above all else, spatial devices in the Yale panel are exceptionally accomplished, if not quite Albertian. The semicircular projection of Charlemagne’s palace at the left, while derived from simpler examples within the Charles III of Durazzo group or the workshop practice of another contemporary artist, Mariotto di Nardo, takes some pains to rationalize foreshortening and single-source lighting effects, especially evident in the corbel frieze that runs along the back wall and outer face of the throne room. The four brothers kneeling before the emperor, and again before the sultan at the right of the panel, are properly foreshortened and, in some instances, seen fully from behind, an exceptional rarity in this period. Their horses are rendered with reasonable anatomical accuracy and in one instance gratuitously posed turning backward into space. Even the emblematic plants and grasses that dot the landscape are studiously foreshortened, while the orthogonals of the simple tower in the background at the right converge correctly in an empirical, if not mathematical, perspective. The draperies of all the figures reflect the movements of the bodies they cover, some in visually credible response to the motions of kneeling or leaning backward, and each figure is beautifully drawn and animated to convey the tenor of the narrative.

In all these respects, the Yale panel can be compared only to two other works of art sometimes associated with the Master of Charles III of Durazzo. A cassone panel in the Bowdoin College Museum of Art, Brunswick, Maine (fig. 1), illustrating Boccaccio’s poem of the Ninfale fiesolano, was originally included by Fahy in his list of the Master’s works but later deleted in favor of Callmann’s attribution of it to Giovanni di Francesco Toscani.16 This much-damaged painting was extensively repainted during a cleaning and restoration by Dianne Dwyer Modestini in 2004 and so cannot be compared directly to the Yale panel for similarities of figure style, but the two works do share many of the same accomplishments of spatial imagination and narrative scansion. Equally suggestive are similarities to a full painted cassone of unknown whereabouts, recorded in old Brogi photographs preserved in the Fototeca Zeri, where they are filed as “Anonimo Fiorentino, XIV/XV secolo” (fig. 2). In this case, the chest is of the more fanciful pastiglia framing type and possibly, therefore, earlier than the Yale panel. Its figure types are all but illegible except for their proportions and attitudes, but the architectural settings for each of the three unidentified scenes portrayed on the chest are remarkable both for their originality and accomplishment. A third chest, slightly less ambitious than this one in its architectural settings and more heavily repainted, was formerly in the Marczell von Nemes collection and subsequently with the dealer Bohler in Munich.17

It is impossible to say with confidence—given their deteriorated condition and widely varying current states of presentation—whether any two or more of these works of art were the product of a single creative mind, but it is also difficult to believe that more than one anonymous painter with such similarly developed skills might have been active within the same narrow arc of time and yet unknown by any other paintings than these. It is possible that they are the only surviving record of an important artist who deserves to be better known—a “Master of the Bowdoin Ninfale,” so to speak—or that they represent a previously unrecognized phase in the career of an artist who has not otherwise been credited with this category of work. —LK

Published References

Schubring, Paul. “New Cassone Panels.” Apollo 3, no. 17 (May 1926): 250–57., 252–53; Seymour, Charles, Jr. Early Italian Paintings in the Yale University Art Gallery. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1970., 138, 314, no. 96; Fredericksen, Burton B., and Federico Zeri. Census of Pre-Nineteenth-Century Italian Paintings in North American Public Collections. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1972., 600; Watson, Paul F. “A Preliminary List of Subjects from Boccaccio in Italian Painting, 1400–1550.” Studi sul Boccaccio 15 (1985–86): 149–66., 154; Boskovits, Miklós. “Il Maestro di Incisa Scapaccino e alcuni problemi di pittura tardogotica in Italia.” Paragone 42, no. 501 (November 1991): 35–53., 47n14; Callmann, Ellen. “Subjects from Boccaccio in Italian Painting, 1375–1525.” Studi sul Boccaccio 23 (1995): 19–78., 65

Notes

-

Schubring, Paul. “New Cassone Panels.” Apollo 3, no. 17 (May 1926): 250–57., 252–53. ↩︎

-

Seymour, Charles, Jr. Early Italian Paintings in the Yale University Art Gallery. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1970., 138, no. 96. ↩︎

-

Watson, Paul F. “A Preliminary List of Subjects from Boccaccio in Italian Painting, 1400–1550.” Studi sul Boccaccio 15 (1985–86): 149–66., 154. ↩︎

-

Callmann, Ellen. “Subjects from Boccaccio in Italian Painting, 1375–1525.” Studi sul Boccaccio 23 (1995): 19–78., 65. ↩︎

-

See Rajna, Pio. Rinaldo da Montalbano. Bologna: Garagnani, 1870.; and da Barberino, Andrea. Le storie di Rinaldo da Montalbano. Ed. Paolo Orvieto. Rome: Aracne, 2020.. The correct identification of the subject was first suggested by Pia Palladino. ↩︎

-

Ellen Callmann, curatorial files, Department of European Art, Yale University Art Gallery. ↩︎

-

Fredericksen, Burton B., and Federico Zeri. Census of Pre-Nineteenth-Century Italian Paintings in North American Public Collections. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1972., 600. ↩︎

-

Schubring, Paul. “New Cassone Panels.” Apollo 3, no. 17 (May 1926): 250–57., 252–53; Seymour, Charles, Jr. Early Italian Paintings in the Yale University Art Gallery. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1970., 138, no. 96; Watson, Paul F. “A Preliminary List of Subjects from Boccaccio in Italian Painting, 1400–1550.” Studi sul Boccaccio 15 (1985–86): 149–66., 154; and Callmann, Ellen. “Subjects from Boccaccio in Italian Painting, 1375–1525.” Studi sul Boccaccio 23 (1995): 19–78., 65. ↩︎

-

Note recorded in the Frick Art Reference Library, New York. ↩︎

-

Fahy, cited in Boskovits, Miklós. “Il Maestro di Incisa Scapaccino e alcuni problemi di pittura tardogotica in Italia.” Paragone 42, no. 501 (November 1991): 35–53., 47n14; Metropolitan Museum of Art, inv. no. 07.120.1, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/437001. ↩︎

-

Boskovits, Miklós. “Il Maestro di Incisa Scapaccino e alcuni problemi di pittura tardogotica in Italia.” Paragone 42, no. 501 (November 1991): 35–53., 47–48n14. ↩︎

-

Fahy, Everett. “Florence and Naples: A Cassone Panel in the Metropolitan Museum of Art.” In Hommage à Michel Laclotte: Études sur la peinture du moyen âge et de la Renaissance, ed. Pierre Rosenberg et al., 231–43. Milan: Electa, 1994., 231–43. For the Master of San Martino a Mensola, see also Ladis, Andrew. “The Reflective Memory of a Late Trecento Painter: Speculations on the Origins and Development of the Master of San Martino a Mensola.” Arte cristiana 80, no. 752 (September–October 1992): 323–34., 323–34; and Bellosi, Luciano. “Francesco di Michele: Il Maestro di San Martino a Mensola.” Paragone 36 (1985): 57–63., 57–63, where it is proposed that he be identified with the painter Francesco di Michele, known from dated paintings ranging between 1385 and 1395. For discursive overviews of the Master of Charles III of Durazzo as a painter of domestic furniture and his place in Florentine culture of the last quarter of the fourteenth century and the first quarter of the fifteenth century, see Miziołek, Jerzy. “Cassoni istoriati with ‘Torello and Saladin’: Observations on the Origins of a New Genre of Trecento Art in Florence.” In Italian Panel Painting of the Duecento and Trecento, ed. Victor M. Schmidt, 443–69. Studies in the History of Art 61, Center for Advanced Study in the Visual Arts, Symposium Papers 38. Washington, D.C.: National Gallery of Art, 2002., 443–69; and Sbaraglio, Lorenzo. “L’origine dei cassoni istoriati nella pittura Fiorentina.” In Virtù d’amore: Pittura nuziale nel quattrocento fiorentino, 104–13. Exh. cat. Florence: Giunti, 2010., 104–13. ↩︎

-

“Al gruppo così riunito, sostanzialmente omogeneo anche se i singoli numeri spesso sono fortemente deturpati da rifacimenti”; Boskovits, Miklós. “Il Maestro di Incisa Scapaccino e alcuni problemi di pittura tardogotica in Italia.” Paragone 42, no. 501 (November 1991): 35–53., 47–48. ↩︎

-

Inv. no. 160. ↩︎

-

A firm date of 1382 for the Metropolitan Museum chest, proposed by Everett Fahy based on his identification of the battle it portrays, is accepted by Jerzy Miziolek (in Miziołek, Jerzy. “Cassoni istoriati with ‘Torello and Saladin’: Observations on the Origins of a New Genre of Trecento Art in Florence.” In Italian Panel Painting of the Duecento and Trecento, ed. Victor M. Schmidt, 443–69. Studies in the History of Art 61, Center for Advanced Study in the Visual Arts, Symposium Papers 38. Washington, D.C.: National Gallery of Art, 2002., 8n6, 34–37, 63–66, pls. 14, 16, 17, 27a) and Lorenzo Sbaraglio (in Sbaraglio, Lorenzo. “L’origine dei cassoni istoriati nella pittura Fiorentina.” In Virtù d’amore: Pittura nuziale nel quattrocento fiorentino, 104–13. Exh. cat. Florence: Giunti, 2010., 105–7), both of whom use it as the basis for dating the beginning of the full series of works attributed to the so-called Master of Charles III of Durazzo. Luciana Mocciola (in Mocciola, Luciana. “La presa di Napoli di Carlo III di Durazzo nel pannello del Metropolitan Museum: Nuove ipotesi.” In La battaglia nel Rinascimento meridionale: Moduli narrative tra parole e immagini, ed. Giancarlo Abbamonte et al., 57–67. Rome: Viella, 2011., 57–67) has instead argued, persuasively, that the Metropolitan Museum chest should be dated 1402, as a commission celebrating the marriage of Ladislaus of Durazzo with Maria di Lusignano, whose heraldic devices decorate the frame surrounding the battle scene. She has also suggested, plausibly, that the chest was manufactured in Naples, not Florence. Both of these suggestions further contribute to refuting the notion of a single Florentine workshop responsible for the heterogeneous production currently associated with the label “Master of Charles III of Durazzo.” ↩︎

-

Fahy, Everett. “Florence and Naples: A Cassone Panel in the Metropolitan Museum of Art.” In Hommage à Michel Laclotte: Études sur la peinture du moyen âge et de la Renaissance, ed. Pierre Rosenberg et al., 231–43. Milan: Electa, 1994., 242n26. The Bowdoin cassone was attributed with hesitation to the young Fra Angelico by the present author, in Kanter, Laurence, and Pia Palladino, eds. Fra Angelico. Exh. cat. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2005., 19–21. This attribution was overambitious but highlighted the irreconcilable differences between this painting and imitations of it by Giovanni Toscani. Everett Fahy (oral communication) agreed with this conclusion. ↩︎

-

Schubring, Paul. Cassoni: Truhen und Truhenbilder der italienischen Frührenaissance. Leipzig, Germany: K. W. Hiersemann, 1915., pl. 15. In a note in the curatorial files, Department of European Art, Yale University Art Gallery, Ellen Callmann associated this chest with the present one, along with one formerly in the collection of Sir George Nelson; sale, London, Sotheby’s, December 2, 1964, lot 94. ↩︎