on base of the modern frame, S[AN]C[TU]S ALBERTUS. S[AN]C[TU]S PETRUS APOSTOL[US]. ANNO DOMINI MCCC[C]XX DIE XV APRILIS. S[AN]C[TU]S PAULUS. S[AN]C[TU]S ANTONIUS ABBAS.

Convent of Santa Maria delle Selve, Lastra a Signa (Florence); James Jackson Jarves (1818–1888), Florence, by 1859

The three main panels of the altarpiece, all of a vertical wood grain, have been cut out of their engaged frame moldings, waxed, cradled, and reinserted into a modern frame that incorporates the original tympanum moldings, regessoed and regilt. The lateral panels have both been thinned to a depth of 2 centimeters; the central panel retains its original thickness of 3 centimeters. The predella and all the vertical members of the frame, including the spiral colonettes dividing the three compartments, are modern. Repairs over nail holes at the top of the halo of each saint and on either side of the Virgin at the level of her cheeks indicate the placement of a cross batten at this height. No evidence of a corresponding cross batten occurs along the bottoms of the panels, which, together with the truncation of the angels in the central compartment, indicates the loss of at least 6 centimeters, probably more, at this edge. A split in the central compartment extending the full height of the panel and running through the Virgin’s right hand, as well as minor splits through the kneeling angels, have provoked local losses in the paint surface, now retouched. Three less prominent splits appear in the left panel and one appears in the right panel. The gold ground has been evenly abraded throughout, more so along the profile of the arches in all three panels and in the haloes of the Virgin, the Christ Child, and Saint Peter. The paint surface generally is well preserved, with the conspicuous exception of the Virgin’s blue robe, which is much deteriorated and was retouched in a stipple technique by Andrew Petryn in a cleaning of 1950–52. The flesh tones of the Virgin are worn. Red lake glazes in Saint Paul’s robes have been lost, and his silver sword is restored with red paint simulating exposed bole. The angels in the central compartment and the draperies in the left compartment are exceptionally well preserved. The three tympanum roundels—measuring, from left to right, 25.5, 22, and 24.5 centimeters in diameter—have been less abraded than the paint surfaces in the panels below them, but prominent splits, vertical in the right tympanum and roundel and diagonal in the center, have not been repaired.

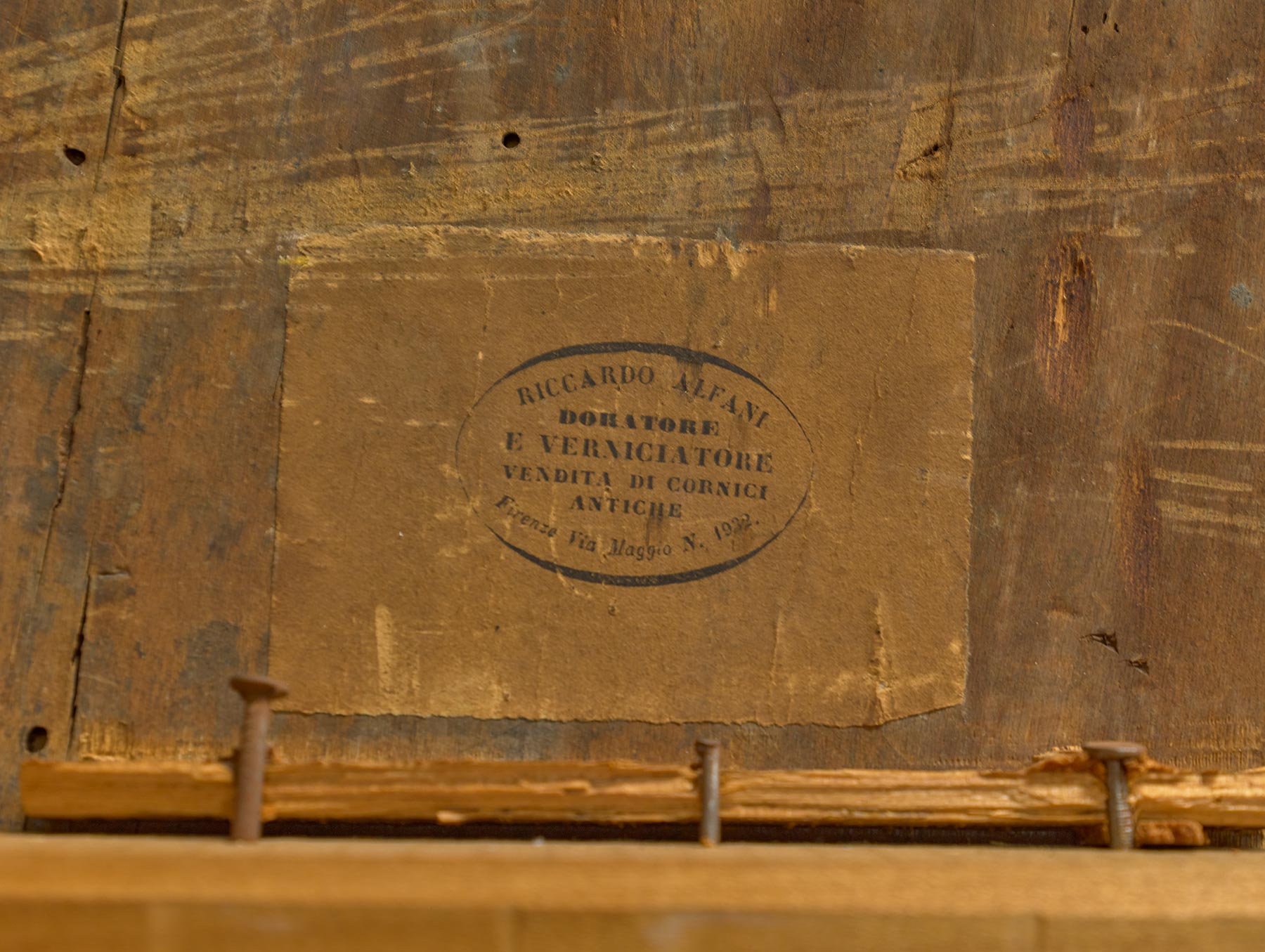

The central compartment of this large triptych shows the enthroned Virgin supporting a lively, robust Christ Child, Who holds a bird in His left hand and raises His right in blessing. The presence of holes on either side of the Virgin’s and Child’s heads indicates where crowns were formerly affixed to the painted surface. Kneeling at the base of the raised marble throne are two music-making angels; the one on the left plays a lute, the other a fiddle. The Virgin is seated on a white brocaded cushion with gold tassels against a bright red cloth of honor decorated with an intricate gold pattern. She wears a blue cloak lined with green over a gold-embroidered white tunic. The Child is swaddled in a blue cloth with gold edging and a pink-and-green blanket with yellow highlights and gold trim. In the left compartment is the Carmelite saint Albert of Trapani (ca. 1240–1307), identified by the white-and-gray Carmelite habit and lily. He is accompanied by Saint Peter, who occupies the position of honor on the Virgin’s right and is dressed in a blue tunic and glowing yellow cape. On the Virgin’s left is Saint Paul, enveloped in an amethyst-colored cape lined in bright orange. Next to him is Saint Anthony Abbot, accompanied by his traditional attribute of a black pig at his feet. In the three pinnacle roundels are the Annunciatory Angel, the Blessing Redeemer, and the Virgin Annunciate. At an unknown date, the three panels were all cut at the bottom and inserted into a nineteenth-century frame. Pasted onto the back of the picture is the label of the nineteenth-century Florentine “gilder, glazer and seller of antique frames,” Riccardo Alfani, who may have been responsible for the earliest restorations (fig. 1). Inscribed on the modern base but obscured by grime are the saints’ names and the purported date of completion, April 15, 1420. The year was reported as “1370” by James Jackson Jarves but later corrected to “1420” by Osvald Sirén.1 There is no technical or documentary evidence to support the assertion by Charles Seymour, Jr., that “it is virtually certain” that the inscription, which is never mentioned in the earliest records of the painting predating Jarves’s purchase, replicates one that had been on the original frame.2

The first indication of the triptych’s provenance was provided by Jarves, who stated that it came from “the suppressed convent of San Martini [sic] alle Selve, at Signa, near Florence.”3 Seymour, who did not recognize the name of the convent as reported by Jarves but acknowledged that the presence of Saint Albert suggested a Carmelite commission, proposed that it may have been executed for the famous church of Santa Maria del Carmine in Florence, consecrated in 1422, and transferred to Signa at a later date.4 As intuited by Boskovits, however, Jarves had most likely conflated the name of the Carmelite convent of Santa Maria delle Selve, located in the woods above Lastra a Signa, with that of the nearby parish church of San Martino at Gangalandi in Lastra a Signa.5 Boskovits tentatively proposed that the circumstances of the commission for the Yale triptych might be related to the renewed importance of the Selve community after 1413, when it became the center of the Observant Carmelite reform movement. Linda Pisani subsequently confirmed that the Yale altarpiece had been removed from Santa Maria delle Selve by connecting this work to an unspecified nineteenth-century inventory that listed the presence in that church of a Giottesque triptych with Saints Peter, Paul, Albert, and Anthony Abbot.6 Pisani followed Seymour, however, in surmising that the work had been originally commissioned for the Florentine motherhouse of Santa Maria del Carmine.7

Although still debated in some of the most recent literature,8 the intended location of the Yale altarpiece was conclusively established by Gioia Romagnoli in 2005, in a detailed study of Santa Maria delle Selve from its foundation in 1344 to its suppression in 1808.9 Among the documents consulted by Romagnoli was an 1818 inventory compiled by the parish priest of San Martino a Gangalandi, who had been placed in charge of the suppressed convent the previous year. The prelate described a painting located in the chapter room of Santa Maria delle Selve in the following terms: “A picture . . . in tempera representing the Madonna of the Snow accompanied by Saints Peter, and Paul, Saint Anthony Abbot and Saint Dominic: it is commonly believed that all these images belong to one of the early schools [of painting] and especially that of Giotto.”10 As noted by Romagnoli, there is little doubt that the “Giottesque” altarpiece in the chapter room is the Yale triptych. That the inventory’s author should have confused the rarer image of Saint Albert with more familiar representations of Saint Dominic—traditionally shown with the same attribute of a lily and in similar monastic robes—is perhaps confirmation that there was not, at the time, a legible inscription identifying the saints and that the triptych was already missing its original predella. According to archival sources, the “sides” of the altarpiece—presumably the ends of the predella—bore the arms of the Lotti family, residents in San Iacopo Oltrarno in Florence.11 Sometime in the second half of the fourteenth century, the Lotti had acquired the patronage of the convent’s chapter room, where they erected a small chapel and located their family tombs.12 The presence of Saint Peter in the position of honor to the Virgin’s right in the Yale triptych, as persuasively argued by Romagnoli, may indicate that the work was commissioned for this chapel by Piero Lotti (born 1365), who would have paid homage to his father, Paolo Lotti, by the inclusion of the latter’s name-saint opposite his own.

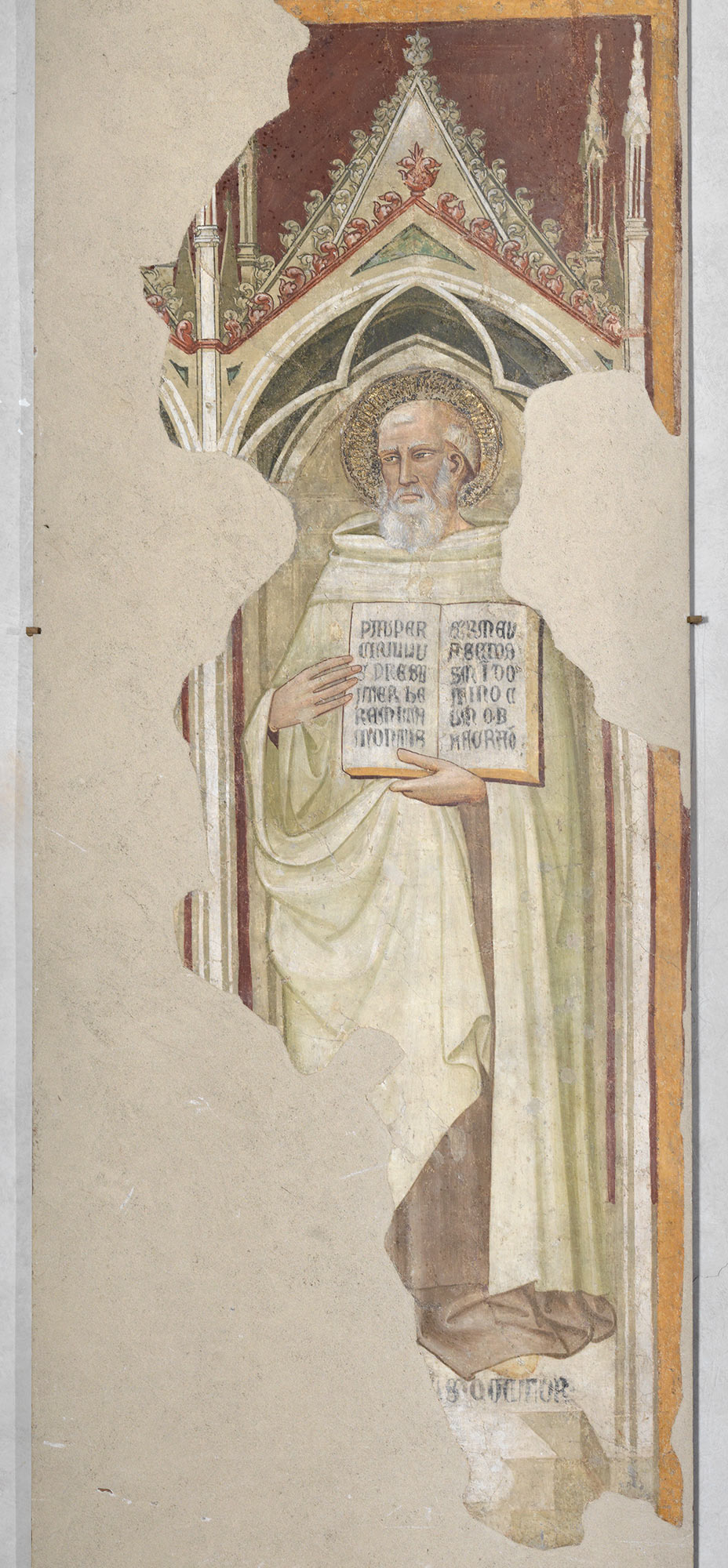

Since Sirén’s placement of the Yale altarpiece at the head of a group of images he attributed to Ambrogio di Baldese,13 subsequently recognized as products of a later hand christened “Pseudo-Ambrogio di Baldese,”14 the present work has been a benchmark in the reconstruction of this painter’s career. Following Serena Padovani, who first proposed identifying the artist with Lippo d’Andrea, the date “1420” inscribed on the altarpiece’s frame has been generally regarded as one of the few fixed points in his chronology. The relevance of the date was further highlighted by Megan Holmes, who pointed out that it coincided with a declaration by the Carmelite general chapter in 1420 that “in every convent an image of Beato Alberto with rays should be painted.”15 In light of these circumstances, the altarpiece’s location in the chapter room of Santa Maria delle Selve, where the most important gatherings of the congregation were held, takes on added significance. It is possible, however, that the later inscription, whose authenticity remains in question, merely commemorated the 1420 edict, especially given the likely existence of earlier paintings of Saint Albert in the same convent. By the end of the fourteenth century, in fact, the cult of Saint Albert, promoted immediately after his death in 1307, had already spread from his native Messina to other parts of Sicily and Italy. Carmelite efforts to gain recognition for a modern founder-figure who could rival Saints Francis and Dominic in stature soon led to petitions for Albert’s canonization, starting at the general chapter meeting of 1375 in Le Puy-en-Velay, France. Further petitions to the pope were signed at the general chapters held in Brescia in 1387 and in Santa Maria delle Selve in 1399. By then, Albert, though not officially canonized until 1457, was already revered as a saint in Tuscan communities. A 1391 inventory from Santa Maria del Carmine in Florence records the presence in the church of an ivory casket with the relics of “Sancti Alberti” and of a gilt copper and enamel tabernacle with the relics of “Santo Alberto da Trapani, formerly a brother of Santa Maria del Carmine.”16 The earliest surviving representation of Saint Albert, frescoed by Taddeo di Bartolo around 1406–8 in Siena’s Palazzo Pubblico, already shows the fully developed iconographic type, with halo, lily, and book, as depicted in the Yale altarpiece, indicating that comparable images already existed in ecclesiastical settings and had been unofficially sanctioned by the order well before the 1420 edict.17

Stylistic considerations alone suggest an earlier chronology for the Yale triptych than recorded in the later inscription. The most reliable point of reference for the dating of the altarpiece is the series of works executed by Lippo d’Andrea around 1416 for the church of San Domenico in San Miniato al Tedesco, near Pisa. Assigned to the Pseudo-Ambrogio di Baldese by Federico Zeri, the frescoes on the interior of the facade of San Domenico were first tentatively attributed to Lippo d’Andrea by Serena Padovani, who also recognized the artist’s hand in a panel with Saint Michael from the same church (fig. 2).18 On the basis of comparisons with the Yale triptych, Padovani dated both commissions to the same moment in the artist’s activity, around or slightly earlier than 1420. Sonia Chiodo subsequently refined this chronology with the publication of a 1416 document referring to Lippo d’Andrea as the author of another, stylistically homogeneous set of frescoes in the main chapel of San Domenico, thereby confirming the artist’s identity.19 Like the Yale altarpiece, the artist’s production for San Domenico reflects a progressive softening of the austere monumentality of his earlier frescoes in Santa Maria del Carmine, Florence, while retaining the same predilection for delicate tonalities and brilliant pastels, derived from Agnolo Gaddi. The physiognomic types in the Yale altarpiece are still closely related to the Carmine frescoes, as demonstrated by a comparison of the Virgin and Child with the corresponding figures in one of the lunettes outside the Carmine sacristy chapel (fig. 3) or by the often-noted affinities between the Yale Saint Albert and the figure of Saint Cyril in the Nerli Chapel (fig. 4). The undisputable analogies between the Nerli Chapel and Yale figures prompted Chiodo to significantly postpone the completion of that cycle, traditionally associated with a 1402 document, to just before the Carmine’s consecration in 1422.20 Such comparisons, on the contrary, seem to only confirm the earlier chronology of the present work. The commission should perhaps be viewed less in relation to the 1420 edict than to the Selve’s decision, in 1413, to embrace the observant reform, becoming the de facto spiritual center of the order. The event, of momentous importance for the community and its patrons, would account for the inclusion of Anthony Abbot, the hermit saint, alongside the Lotti family’s name-saints and Saint Albert—as a reminder of the order’s mythical past on Mount Carmel.21 A general time frame for the altarpiece’s execution between around 1413 and 1420 seems plausible.

The issues surrounding the Yale altarpiece suggest a greater scrutiny of Lippo d’Andrea’s chronology and the not-entirely homogeneous body of works currently gathered under his name. Aside from the confusion that still persists between his oeuvre and that of the entirely distinct personality of Ventura di Moro, the evaluation of the artist’s personality has thus far failed to take into account the participation of assistants in his workshop, in what appears to have been a large and busy enterprise active throughout Tuscany. Most discussions of the Yale triptych have tended to overlook the qualitative differences in the execution of its various parts, which are evident upon close examination. Some of these discrepancies were already highlighted by Sirén, and later emphasized by Seymour, who went so far as assigning the work to four different painters.22 In an unpublished report to the Yale University Art Gallery, Everett Fahy singled out the figures of Saint Paul and Anthony Abbot as much finer in quality than the rest of the painting, writing that he “would be inclined to see the stylistic differences in the triptych as a result of more than one artist at work.”23 Fahy’s opinion was echoed by Carl Strehlke in his unpublished checklist of Italian paintings at Yale, where the altarpiece was labeled “Lippo d’Andrea and Workshop.” While the distinctions between the saints in the lateral compartments are not always clear, it is almost impossible to ignore the contrast between the careful handling and finish of the two elegant angels kneeling at the base of the Virgin’s throne and the more relaxed approach to the Annunciatory Angel in the pinnacle above. The tightly drawn features and nuanced modeling of the two angels also depart from the flatter, more generalized forms that define the other two roundels and, to a certain degree, the Virgin and Child. The identity of this undoubtedly more accomplished collaborator in Lippo’s workshop remains, for the moment, unknown. —PP

Published References

Jarves, James Jackson. Descriptive Catalogue of “Old Masters” Collected by James J. Jarves to Illustrate the History of Painting from A.D. 1200 to the Best Periods of Italian Art. Cambridge, Mass.: H. O. Houghton, 1860., 46, no. 37; Sturgis, Russell, Jr. Manual of the Jarves Collection of Early Italian Pictures. New Haven: Yale College, 1868., 29–30, no. 16; W. F. Brown, Boston. Catalogue of the Jarves Collection of Early Italian Pictures. Sale cat. November 9, 1871., 13–14, lot 16; Rankin, William. “Some Early Italian Pictures in the Jarves Collection of the Yale School of Fine Arts at New Haven.” American Journal of Archaeology 10, no. 2 (April–June 1895): 137–51., 140; Sirén, Osvald. “Trecento Pictures in American Collections—III.” Burlington Magazine 14, no. 71 (February 1909): 325–26., 326, pl. 2, no. 2; Sirén, Osvald. A Descriptive Catalogue of the Pictures in the Jarves Collection Belonging to Yale University. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1916., 57–62, no. 22; van Marle, Raimond. The Development of the Italian Schools of Painting. Vol. 9. The Hague: M. Nijhoff, 1927., 87; Offner, Richard. Italian Primitives at Yale University: Comments and Revisions. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1927., 19–20, fig. 11; Berenson, Bernard. Italian Pictures of the Renaissance: A List of the Principal Artists and Their Works with an Index of Places. Oxford: Clarendon, 1932., 195; Procacci, Ugo. “Opere d’arte inedite alla mostra del tesoro di Firenze sacra.” Rivista d’arte 15 (1933): 224–44., 240n3, 242; Pudelko, Georg. “The Minor Masters of the Chiostro Verde.” Art Bulletin 17, no. 1 (1935): 71–89., 84, 88; Rediscovered Italian Paintings. Exh. cat. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1952., 20–21; Hess, Albert G. Italian Renaissance Paintings with Musical Subjects: A Corpus of Such Works in American Collections, with Detailed Descriptions of the Musical Features. New York: Libra, 1955., no. 70b; Berenson, Bernard. Italian Pictures of the Renaissance, A List of the Principal Artists and Their Works with an Index of Places: The Florentine School. 2 vols. London: Phaidon, 1963., 1:219; Seymour, Charles, Jr. Early Italian Paintings in the Yale University Art Gallery. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1970., 112–14, no. 77; Fredericksen, Burton B., and Federico Zeri. Census of Pre-Nineteenth-Century Italian Paintings in North American Public Collections. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1972., 599; Charles Seymour, Jr., in Seymour, Charles, Jr., et al. Italian Primitives: The Case History of a Collection and Its Conservation. Exh. cat. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1972., 18, no. 9, fig. 9; Gardner von Teuffel, Christa. “Masaccio and the Pisa Altarpiece: A New Approach.” Jahrbuch der Berliner Museen 19 (1977): 23–68., 54nn90, 92, fig. 19, reprinted in Gardner von Teuffel, Christa. From Duccio’s Maestà to Raphael’s Transfiguration: Italian Altarpieces and Their Settings. London: Pindar, 2005., 28–29n92, fig. 19; Serena Padovani, in Tesori d’arte antica a San Miniato. Genoa: Sagep, 1979., 55–56; Kaftal, George. Iconography of the Saints in Tuscan Painting. Florence: Le Lettere, 1986., col. 13, no. 6a, col. 14, fig. 15; Boskovits, Miklós. “Il percorso di Masolino: Precisazioni sulla cronologia e sul catalogo.” Arte cristiana 75 (1987): 47–66., 51–52, 62n20, fig. 6; Brown, Howard Mayer. “Catalogus: A Corpus of Trecento Pictures with Musical Subject Matter, Part II/1, Instalment 4.” Imago musicae 5 (1988): 167–241., 234, no. 676, fig. 676; Guidotti, Alessandro. “Ambrogio di Baldese.” In Allgemeines Künstlerlexikon. Munich: K. G. Saur, 1992., 134–35; Kanter, Laurence. Italian Paintings in the Museum of Fine Arts Boston. Volume 1, 13th–15th Century. Boston: Museum of Fine Arts, 1994., 149n1; Holmes, Megan. Fra Filippo Lippi: The Carmelite Painter. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1999., 39, 252n55, figs. 31–32; Pisani, Linda. “Pittura tardogotica a Firenze negil anni trenta del quattrocento: Il caso dello Pseudo-Ambrogio di Baldese.” Mitteilungen des Kunsthistorischen Institutes in Florenz 45, nos. 1–2 (2001): 1–36., 8, 10, 33n29, fig. 12; Chiodo, Sonia. “Lippo d’Andrea: Problemi di iconografia e stile.” Arte cristiana 90 (2002): 1–16., 1, 10–11, fig. 1; Rowlands, Eliot W. Masaccio: Saint Andrew and the Pisa Altarpiece. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2003., 82, 105n208, fig. 70; Staderini, Andrea. “‘Primitivi’ fiorentini dalla collezione Artaud de Montor: Parte I, Lippo d’Andrea e Stefano d’Antonio.” Arte cristiana 92, no. 823 (2004): 259–66., 261; de Vries, Anneke. “Schilderkunst in Florence tussen 1400 en 1430: Een onderzoek naar stijl en stilistische vernieuwing.” Ph.D. diss., University of Leiden, 2004., 108, 199–200, fig. 247; Sonia Chiodo, in Boskovits, Miklós, and Daniela Parenti, eds. Da Bernardo Daddi al Beato Angelico a Botticelli: Dipinti fiorentini del Lindenau-Museum di Altenburg. Exh. cat. Florence: Giunti, 2005., 106, 108, fig. 1; Romagnoli, Gioia. Selve e Lecceto: Due conventi a Lastra a Signa ed un grande mecenate, Filippo Strozzi; Arte e storia. Florence: Polistampa, 2005., 71–73, pl. 15; Chiodo, Sonia. “Gli affreschi della chiesa di San Domenico a San Miniato: Un capitol poco noto della pittura fiorentina fra tre e quattrocento (Parte II).” Arte cristiana 96, no. 845 (2008): 81–94., 87–88; Katherine Smith Abbott, in Smith Abbott, Katherine, Wendy Watson, Andrea Rothe, and Jeanne Rothe. The Art of Devotion: Panel Painting in Early Renaissance Italy. Exh. cat. Middlebury, Vt.: Middlebury College Museum of Art, 2009., 88–89, no. 7; Linda Pisani, in Caioni, Gabriele. The Middle Ages and Early Renaissance: Paintings and Sculptures from the Carlo De Carlo Collection and Other Provenance. Florence: Centro Di, 2011., 88, 93, fig. 1; Gardner von Teuffel, Christa. “The Carmelite Altarpiece (circa 1290–1550): The Self-Identification of an Order.” Mitteilungen des Kunsthistorischen Institutes in Florenz 57, no. 1 (January 2015): 3–42., 19, fig. 20; Gardner von Teuffel, Christa. “Locating Albert: The First Carmelite Saint in the Works of Taddeo di Bartolo, Lippo di Andrea, Masaccio and Others.” Predella 39–40 (2018): 173–92., 174–75, 177–78, 186n7; Emilia Ludovici, in Hollberg, Cecilie, Angelo Tartuferi, and Daniela Parenti, eds. Cataloghi della Galleria dell’Accademia di Firenze: Dipinti. Vol. 3, Il tardogotico. Florence: Giunti, 2020., 98; Daniela Parenti, in Hollberg, Cecilie, Angelo Tartuferi, and Daniela Parenti, eds. Cataloghi della Galleria dell’Accademia di Firenze: Dipinti. Vol. 3, Il tardogotico. Florence: Giunti, 2020., 89, 95

Notes

-

Jarves, James Jackson. Descriptive Catalogue of “Old Masters” Collected by James J. Jarves to Illustrate the History of Painting from A.D. 1200 to the Best Periods of Italian Art. Cambridge, Mass.: H. O. Houghton, 1860., 46, no. 37; and Sirén, Osvald. “Trecento Pictures in American Collections—III.” Burlington Magazine 14, no. 71 (February 1909): 325–26., 326, pl. 2, no. 2. In a visit to the Gallery on January 5, 1930 (recorded in curatorial files, Department of European Art, Yale University Art Gallery), Raimond van Marle noted that the date could be read as either MCCCLXX (1370) or MCCCCXX (1420) but was more probably 1420. ↩︎

-

Seymour, Charles, Jr. Early Italian Paintings in the Yale University Art Gallery. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1970., 114. ↩︎

-

Jarves, James Jackson. Descriptive Catalogue of “Old Masters” Collected by James J. Jarves to Illustrate the History of Painting from A.D. 1200 to the Best Periods of Italian Art. Cambridge, Mass.: H. O. Houghton, 1860., 46. ↩︎

-

Seymour, Charles, Jr. Early Italian Paintings in the Yale University Art Gallery. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1970., 114. ↩︎

-

Boskovits, Miklós. “Il percorso di Masolino: Precisazioni sulla cronologia e sul catalogo.” Arte cristiana 75 (1987): 47–66., 62n20. ↩︎

-

Pisani, Linda. “Pittura tardogotica a Firenze negil anni trenta del quattrocento: Il caso dello Pseudo-Ambrogio di Baldese.” Mitteilungen des Kunsthistorischen Institutes in Florenz 45, nos. 1–2 (2001): 1–36., 33n29. ↩︎

-

It should be noted, in this context, that there is presently no indication on the back of the Yale panels of an inscription referred to by Pisani (in Pisani, Linda. “Pittura tardogotica a Firenze negil anni trenta del quattrocento: Il caso dello Pseudo-Ambrogio di Baldese.” Mitteilungen des Kunsthistorischen Institutes in Florenz 45, nos. 1–2 (2001): 1–36., 33n29) recording the altarpiece’s removal from the Selve. ↩︎

-

Gardner von Teuffel, Christa. “Locating Albert: The First Carmelite Saint in the Works of Taddeo di Bartolo, Lippo di Andrea, Masaccio and Others.” Predella 39–40 (2018): 173–92., 174–75. ↩︎

-

Romagnoli, Gioia. Selve e Lecceto: Due conventi a Lastra a Signa ed un grande mecenate, Filippo Strozzi; Arte e storia. Florence: Polistampa, 2005., 72–73, pl. 15. ↩︎

-

Quoted in Romagnoli, Gioia. Selve e Lecceto: Due conventi a Lastra a Signa ed un grande mecenate, Filippo Strozzi; Arte e storia. Florence: Polistampa, 2005., 72. ↩︎

-

Unfortunately, Ettore Romagnoli does not transcribe or note the date of the document in question, cited as Archivio di Stato, Florence, Corporazioni religiose soppresse dal governo francese, 253, Santa Maria delle Selve, no. 46, Scritture II (the items in “253” apparently cover the period from 1392 to 1808); see Romagnoli, Gioia. Selve e Lecceto: Due conventi a Lastra a Signa ed un grande mecenate, Filippo Strozzi; Arte e storia. Florence: Polistampa, 2005., 72–73, 88n289. ↩︎

-

The Lotti arms, as pointed out in Romagnoli, Gioia. Selve e Lecceto: Due conventi a Lastra a Signa ed un grande mecenate, Filippo Strozzi; Arte e storia. Florence: Polistampa, 2005., are still visible above the door to the chapter room and in the later furnishing still in situ. The Lotti held the patronage until the family’s extinction in the seventeenth century. ↩︎

-

Sirén, Osvald. A Descriptive Catalogue of the Pictures in the Jarves Collection Belonging to Yale University. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1916., 58–62. ↩︎

-

van Marle, Raimond. The Development of the Italian Schools of Painting. Vol. 9. The Hague: M. Nijhoff, 1927., 87. ↩︎

-

Holmes, Megan. Fra Filippo Lippi: The Carmelite Painter. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1999., 39. ↩︎

-

Holmes, Megan. Fra Filippo Lippi: The Carmelite Painter. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1999., 39, 251–52n51. ↩︎

-

Gardner von Teuffel, Christa. “Locating Albert: The First Carmelite Saint in the Works of Taddeo di Bartolo, Lippo di Andrea, Masaccio and Others.” Predella 39–40 (2018): 173–92., 176 (with previous bibliography). Taddeo di Bartolo’s image in Siena was reportedly accompanied by the following inscription, now no longer visible: SANCTUS ALBERTUS ORDINIS SANTE MARIE DE MONTE CARMELO. ↩︎

-

Serena Padovani, in Tesori d’arte antica a San Miniato. Genoa: Sagep, 1979., 55–56. ↩︎

-

Chiodo, Sonia. “Gli affreschi della chiesa di San Domenico a San Miniato: Un capitol poco noto della pittura fiorentina fra tre e quattrocento (Parte II).” Arte cristiana 96, no. 845 (2008): 81–94., 87–88. ↩︎

-

Chiodo, Sonia. “Lippo d’Andrea: Problemi di iconografia e stile.” Arte cristiana 90 (2002): 1–16., 10–11. ↩︎

-

The relevance of the figure of Saint Anthony Abbot in the Yale altarpiece was pointed out by Christa Gardner von Teuffel (in Gardner von Teuffel, Christa. “Locating Albert: The First Carmelite Saint in the Works of Taddeo di Bartolo, Lippo di Andrea, Masaccio and Others.” Predella 39–40 (2018): 173–92., 178), although the author, who appears to have been unaware of Romagnoli’s study, associated the work with a commission from Santa Maria del Carmine. ↩︎

-

Sirén, Osvald. A Descriptive Catalogue of the Pictures in the Jarves Collection Belonging to Yale University. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1916., 58; and Seymour, Charles, Jr. Early Italian Paintings in the Yale University Art Gallery. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1970., 114. ↩︎

-

Curatorial files, Department of European Art, Yale University Art Gallery. ↩︎