James Jackson Jarves (1818–1888), Florence, by 1859

The panel support, of a vertical wood grain, has been thinned to a depth of 7 millimeters. It was cradled by Hammond Smith in 1915, ostensibly to stabilize the crack running the full height of the painting down its center. The cradle provoked a noticeable washboard effect on the surface and forced at least nine more partial splits to open. All the horizontal members and one vertical member of the cradle were removed during a radical cleaning by Andrew Petryn in 1966–68, while the remaining vertical members of the cradle were removed by Giovanni Marrussich at the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, in 1998–99. At that time, the splits were remediated by carving a V-shaped channel through each from the reverse, to a level just beneath the original canvas lining of the panel. Short, triangular wedges carved of aged poplar were glued into these channels to limit but not block lateral movement of the panel. Broken and detached elements of the original frame were reattached, regessoed, and regilt.

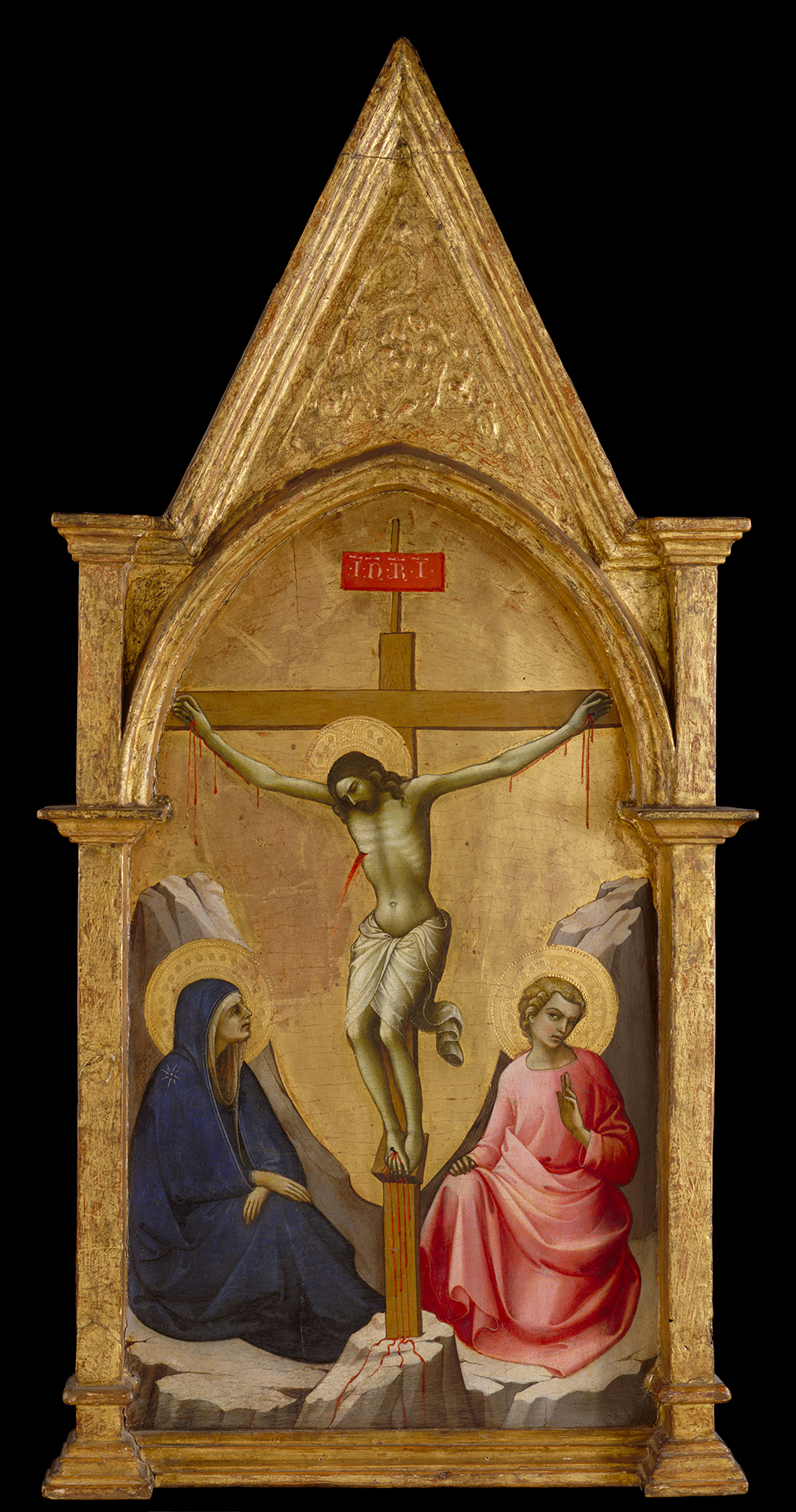

The gold ground is heavily abraded throughout, exposing its red bolus underlayer except around the profiles of the painted areas and in the stippled decoration of the haloes and borders, where the gold is better preserved in the recesses. The painted landscape elements and the wood of the Cross are well preserved, but the figures are heavily abraded: the face and right hand of God the Father are inventions of the 1998–99 Getty restoration by Mark Leonard. The Virgin’s face is better preserved than the others but still rubbed to the level of its terra verde preparation. The Virgin’s blue draperies and Saint John’s red draperies have been heavily reinforced with thin glazes of pigment. Total losses of paint and gilding along the wide split through Christ’s head and right leg have been fully reintegrated.

“Had this little picture not suffered by a crack running through the whole panel, from the top to the bottom, it would be one of the most refined examples of Lorenzo Monaco’s art.”1 So wrote Osvald Sirén when cataloguing the Crucifixion in 1916, an accurate assessment of the elevated quality of a great but damaged work of art from the scholar who had first systematically isolated and synthesized the personality of the artist. Prior to the publication in 1905 of Sirén’s monograph on Lorenzo Monaco, where the Jarves Crucifixion first appeared with its correct attribution, it had been catalogued by James Jackson Jarves and others as the work of Giotto;2 by William Rankin with the unhelpful clarification “later than Giotto”;3 and by F. Mason Perkins with a strangely aberrant Sienese classification as “school of Bartolo di Fredi.”4 Since then, there have been no dissenting voices other than Georg Pudelko’s and Marvin Eisenberg’s overscrupulous but unfounded qualification of workshop or assistant of Lorenzo Monaco and Charles Seymour’s inexplicable assignment to an independent follower of Lorenzo Monaco.5

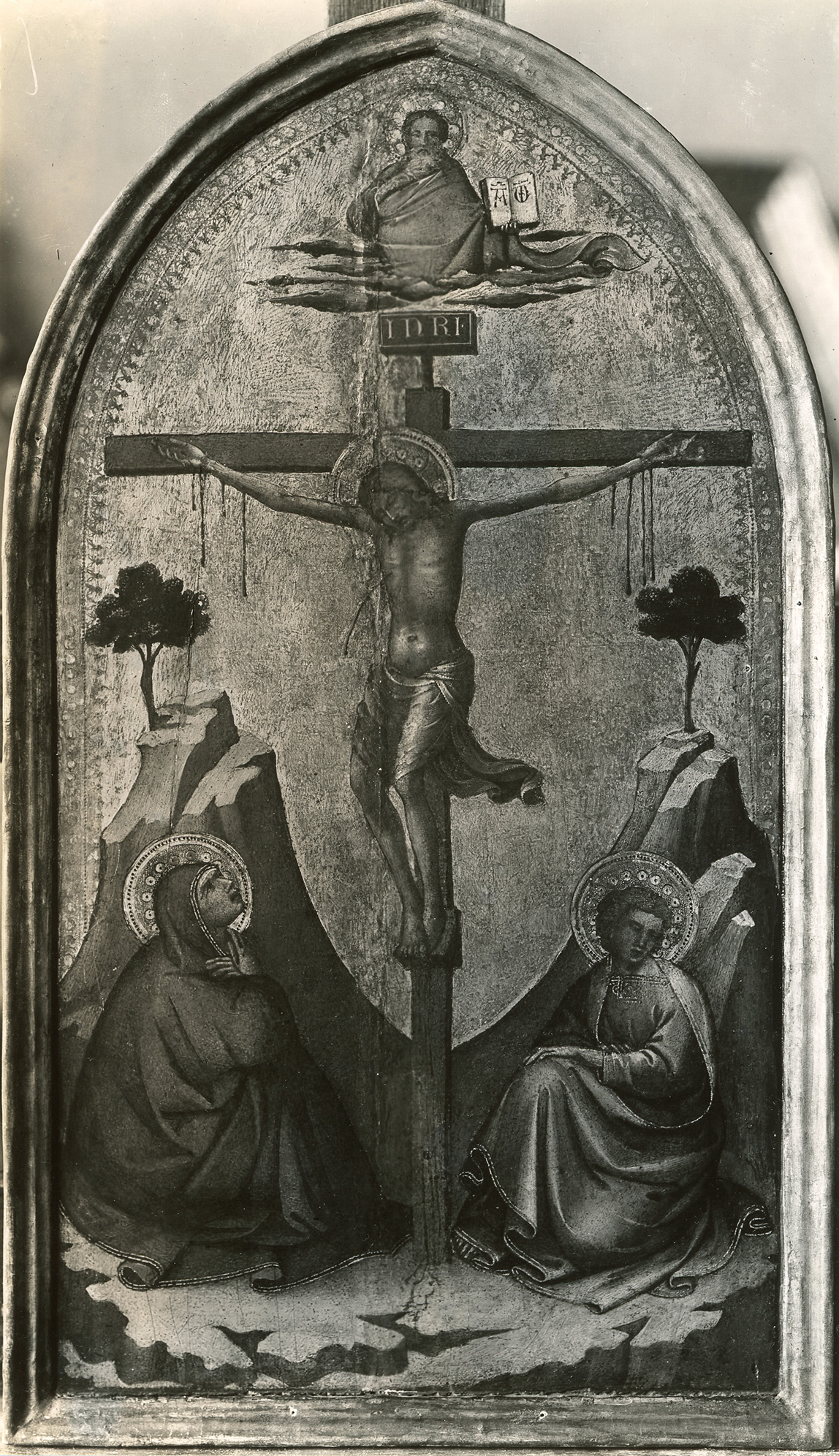

All these scholars have known the painting in different states of preservation but not so widely varying that they should have materially influenced judgments of attribution. A ca. 1901 photograph (fig. 1) shows the painting with the split in the panel repainted in poorly matched colors, with losses and retouching in the head of Saint John the Evangelist, and with reinforcements in the draperies of the Virgin, but otherwise fully legible as a mature work by Lorenzo Monaco. A cleaning by Hammond Smith in 1915 corrected the discoloration of the retouching (fig. 2), resulting in a more homogeneous picture surface but much greater confusion in the restored areas. The head of Christ became fuller, rounder, and less easy to recognize as characteristic of any fourteenth- or fifteenth-century Florentine painter; Saint John the Evangelist became a softer and less expressive figure; and the draperies along God the Father’s right arm and Christ’s right leg became formless. A drastic cleaning by Andrew Petryn in 1966–68 reduced the painting to a study-collection object (fig. 3), while in the most recent conservation campaign (1998–99), Mark Leonard filled the splits and losses left exposed thirty years earlier and attempted once again to unify the picture surface, less opaquely than it had been in 1915 but with the same conceptual goal of making it appear to be undamaged other than by light overall abrasion.

There is a near consensus among scholars in dating the Jarves Crucifixion to the last third of Lorenzo Monaco’s career, with only Miklós Boskovits propounding an early date of ca. 1400–1405.6 Erling Skaug’s systematic survey of the punch tools used by Lorenzo Monaco throughout his career tends to support such a view.7 The arcade punch decorating the margins of the gold ground in the Yale panel recurs in the Madonna of Humility at the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., dated by an inscription on the panel to 1413,8 and in the miniaturist diptych of the Madonna of Humility at the Thorvaldsen Museum, Copenhagen,9 and Saint Jerome in His Study at the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam,10 universally considered among the artist’s last works. It is unrecorded by Skaug in any work prior to the Monteoliveto altarpiece of 1410. Precise dating within this final decade of Lorenzo Monaco’s activity is problematic as no securely documented works later than 1415 survive and as two major commissions—for the fresco decoration and Annunciation altarpiece in the Bartolini Salimbeni Chapel in Santa Trinita and for the altarpiece of the Deposition (only the frame of which was ultimately painted by Lorenzo Monaco) now in the Museo di San Marco but also intended for the church of Santa Trinita—are often thought on anecdotal grounds to be the artist’s very last works, although they may have been painted somewhat earlier.

Among all the works reasonably grouped in this final decade, the Jarves Crucifixion most closely resembles, in its figure types, emotional tenor, and drawing style, these two major commissions for Santa Trinita, especially the narrative scenes in the predella to the Annunciation altarpiece in the Bartolini Salimbeni Chapel. It does not share the greater exaggeration of forms, colors, or lighting effects (to the extent that these are still fully legible in the Yale panel) in such paintings from the very end of Lorenzo Monaco’s career as the Adoration of the Magi altarpiece in the Gallerie degli Uffizi, Florence,11 or the Copenhagen/Amsterdam diptych, which may be assumed to date from some time in the 1420s. The Bartolini Salimbeni frescoes and altarpiece have recently been dated by Luciano Bellosi to shortly before 1420.12 Similarly, although the pinnacles and predella from the frame of the Strozzi Deposition are still frequently discussed as Lorenzo Monaco’s last work, left incomplete by the artist at his death,13 they have also and more persuasively been dated between 1418 and 1421, on the assumption that this commission was not left incomplete but rather was assigned to Fra Angelico for revision around 1430 in order to introduce a change in the iconography of the main panel.14 A broadly inclusive date for the Jarves Crucifixion between 1415 and 1420, as had in any event been proposed by Pudelko and Eisenberg, might therefore seem prudent, with the understanding that an execution close to the end of that time span, around or after 1418, is most likely.

It remains to be determined what function the Jarves Crucifixion might originally have fulfilled, as it is in many respects anomalous. In the majority of his depictions of the Crucifixion, Lorenzo Monaco included only the three figures portrayed here and, as in this example, he generally showed the Virgin and Saint John seated on the ground. As such, the paintings are not a reference to the historical event of the Crucifixion nor are they typical of devotional images of this subject in that some of them do not include any of the standard repertory of symbols alluding to the significance of Christ’s sacrifice, such as the pelican in her piety atop the Cross, the skull of Adam at the foot of the Cross, or angels collecting the blood dripping from Christ’s wounds. In two examples, furthermore—the Yale painting and a similar though much earlier composition in the Robert Lehman Collection at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (fig. 4)—the Virgin and Saint John are considerably larger in scale than Christ, further abstracting the scene and casting it almost as a private meditation on the Passion shared by the viewer with the two sacred figures in the foreground. The Metropolitan Museum painting appears to have been conceived as the central pinnacle to an altarpiece, but it is unlikely that the Yale panel was designed for a similar purpose. None of Lorenzo Monaco’s altarpiece fragments have fully decorated margins to their gold grounds, and few retain no evidence whatsoever of the presence of architectural frame elements, such as side pilasters or corbels supporting the ogival pediment.

Only two other works by Lorenzo Monaco share with the Yale panel its elongated vertical proportions and its uninterrupted linear profile fully decorated by continuous punch tooling: the Madonna of Humility of 1413 in the National Gallery of Art and another Madonna of Humility in the center panel of a triptych in the Pinacoteca Nazionale, Siena.15 In the latter, a very early work by Lorenzo Monaco, the engaged frame moldings do not follow the continuous punched margin of the central picture field but rather create an architectural form typical of folding tabernacle triptychs of around 1400. In a slightly later (1408) folding triptych, however, comprising a Lamentation over the Dead Christ in the National Gallery, Prague,16 and the Agony in the Garden and Three Maries at the Tomb now preserved in the Musée du Louvre, Paris,17 the engaged moldings did follow the profile of the uninterrupted ogival picture field, as in the Yale panel, although in this triptych the margins of the gold ground are not decorated with a continuous band of punching. Nevertheless, it is worth speculating whether the Yale panel might once have been part of a triptych, either as the center panel or as one of the folding wings, and whether it might have been completed by a triangular pediment similar to that above the Louvre triptych wings. It should be noted that, unlike other versions of the subject by Lorenzo Monaco, the composition of the Yale Crucifixion is not symmetrical (pace Seymour, who felt that its “emphatic symmetry” argued against an attribution to the master18): the arms of the Cross overlap the punched margin at the right but do not quite reach it at the left, the figure of Saint John on the right is positioned lower than the Virgin, and the hill on the right does not reach as high into the picture field as does the hill on the left. These are not accidental differences, and it may be wondered whether they might have been intended to compensate for a viewing angle commonly encountered in the right wing of a folding diptych or triptych. —LK

Published References

Jarves, James Jackson. Descriptive Catalogue of “Old Masters” Collected by James J. Jarves to Illustrate the History of Painting from A.D. 1200 to the Best Periods of Italian Art. Cambridge, Mass.: H. O. Houghton, 1860., 43, no. 17; Sturgis, Russell, Jr. Manual of the Jarves Collection of Early Italian Pictures. New Haven: Yale College, 1868., 33, no. 18; W. F. Brown, Boston. Catalogue of the Jarves Collection of Early Italian Pictures. Sale cat. November 9, 1871., 14, no. 18; Rankin, William. “Some Early Italian Pictures in the Jarves Collection of the Yale School of Fine Arts at New Haven.” American Journal of Archaeology 10, no. 2 (April–June 1895): 137–51., 140, no. 18; Perkins, F. Mason. “Pitture senesi negli Stati Uniti.” Rassegna d’arte senese 1 (1905): 74–78., 76; Rankin, William. Notes on the Collections of Old Masters at Yale University, the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, the Fogg Museum of Harvard University. Wellesley, Mass.: Department of Art, Wellesley College, 1905., 8, no. 18; Sirén, Osvald. Don Lorenzo Monaco. Strasbourg, France: Heitz, 1905., 91, 102, 142, 189, pl. 34; Berenson, Bernard. The Florentine Painters of the Renaissance with an Index to Their Works. 3rd. ed. New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1909., 153; Sirén, Osvald. “Trecento Pictures in American Collections—III.” Burlington Magazine 14, no. 71 (February 1909): 325–26., 325, pl. 1, no. 1; Venturi, Adolfo. Storia dell’arte italiana. 11 vols. Milan: Ulrico Hoepli, 1901–40., 7, pt. 1: 14–15; Sirén, Osvald. A Descriptive Catalogue of the Pictures in the Jarves Collection Belonging to Yale University. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1916., 67–69, no. 24; van Marle, Raimond. The Development of the Italian Schools of Painting. Vol. 9. The Hague: M. Nijhoff, 1927., 145–48; Offner, Richard. Italian Primitives at Yale University: Comments and Revisions. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1927., 5, 21–22, fig. 12; Suida, Wilhelm. “Lorenzo Monaco.” In Allgemeines Lexikon der bildenden Künstler: Von der Antike bis zur Gegenwart, ed. Ulrich Thieme and Felix Becker. Leipzig, Germany: E. A. Seemann, 1929., 23:392; Venturi, Lionello. Pitture italiane in America. 2 vols. Milan: Ulrico Hoepli, 1931., pl. 42; Berenson, Bernard. Italian Pictures of the Renaissance: A List of the Principal Artists and Their Works with an Index of Places. Oxford: Clarendon, 1932., 300; Venturi, Lionello. Italian Paintings in America. Trans. Countess Vanden Heuvel and Charles Marriott. 3 vols. New York: E. Weyhe, 1933., pl. 135; Pudelko, Georg. “The Stylistic Development of Lorenzo Monaco—I.” Burlington Magazine 73, no. 429 (December 1938): 237–38, 241–42, 247–48., 248n35; Landscape: An Exhibition of Paintings. Exh. cat. Brooklyn: Brooklyn Museum, 1945., 13, no. 1; Berenson, Bernard. Italian Pictures of the Renaissance, A List of the Principal Artists and Their Works with an Index of Places: The Florentine School. 2 vols. London: Phaidon, 1963., 1:120; Seymour, Charles, Jr. Early Italian Paintings in the Yale University Art Gallery. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1970., 161–64, no. 116; Fredericksen, Burton B., and Federico Zeri. Census of Pre-Nineteenth-Century Italian Paintings in North American Public Collections. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1972., 111, 599; Boskovits, Miklós. Pittura fiorentina alla vigilia del Rinascimento, 1370–1400. Florence: Edam, 1975., 350; Eisenberg, Marvin. Lorenzo Monaco. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1989., 79, 127, 143, 149, fig. 174; Laurence Kanter, in Kanter, Laurence, Barbara Drake Boehm, Carl Brandon Strehlke, Gaudenz Freuler, Christa C. Mayer Thurman, and Pia Palladino. Painting and Illumination in Early Renaissance Florence, 1300–1450. Exh cat. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1994., 252; Skaug, Erling S. Punch Marks from Giotto to Fra Angelico: Attribution, Chronology, and Workshop Relationships in Tuscan Panel Painting, with Particular Consideration to Florence, c. 1330–1430. 2 vols. Oslo: International Institute for Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works—Nordic Group, 1994., 1:285, 2: no. 8.13; Dean, Clay. A Selection of Early Italian Paintings from the Yale University Art Gallery. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 2001., 26–27, no. 6; Garland, Patricia Sherwin. “Recent Solutions to Problems Presented by the Yale Collection.” In Early Italian Paintings: Approaches to Conservation; Proceedings of a Symposium at the Yale University Art Gallery, April 2002, ed. Patricia Sherwin Garland, 54–70. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 2003., 59–60, fig. 3.5; Skaug, Erling S. “Notes on the Punched Decoration in Lorenzo Monaco’s Panel Paintings.” In Lorenzo Monaco: A Bridge from Giotto’s Heritage to the Renaissance, ed. Angelo Tartuferi and Daniela Parenti, 53–58. Exh. cat. Florence: Giunti, 2006., 54

Notes

-

Sirén, Osvald. A Descriptive Catalogue of the Pictures in the Jarves Collection Belonging to Yale University. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1916., 68. ↩︎

-

For the work as Giotto, see Jarves, James Jackson. Descriptive Catalogue of “Old Masters” Collected by James J. Jarves to Illustrate the History of Painting from A.D. 1200 to the Best Periods of Italian Art. Cambridge, Mass.: H. O. Houghton, 1860., 43, no. 17; Sturgis, Russell, Jr. Manual of the Jarves Collection of Early Italian Pictures. New Haven: Yale College, 1868., 33, no. 18; and W. F. Brown, Boston. Catalogue of the Jarves Collection of Early Italian Pictures. Sale cat. November 9, 1871., 14, no. 18. For Sirén’s attribution, see Sirén, Osvald. Don Lorenzo Monaco. Strasbourg, France: Heitz, 1905., 91, 102, 142, 189, pl. 34. ↩︎

-

Rankin, William. “Some Early Italian Pictures in the Jarves Collection of the Yale School of Fine Arts at New Haven.” American Journal of Archaeology 10, no. 2 (April–June 1895): 137–51., 140, no. 18. ↩︎

-

Perkins, F. Mason. “Pitture senesi negli Stati Uniti.” Rassegna d’arte senese 1 (1905): 74–78., 76. ↩︎

-

Pudelko, Georg. “The Stylistic Development of Lorenzo Monaco—I.” Burlington Magazine 73, no. 429 (December 1938): 237–38, 241–42, 247–48., 248n35; Eisenberg, Marvin. Lorenzo Monaco. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1989., 79, 127, 143, 149, fig. 174; and Seymour, Charles, Jr. Early Italian Paintings in the Yale University Art Gallery. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1970., 161–64, no. 116. ↩︎

-

Boskovits, Miklós. “Una scheda e qualche suggerimento per un catalogo dei dipinti ai Tatti.” Antichità viva 14, no. 2 (1975): 9–21., 350. ↩︎

-

Skaug, Erling S. “Notes on the Punched Decoration in Lorenzo Monaco’s Panel Paintings.” In Lorenzo Monaco: A Bridge from Giotto’s Heritage to the Renaissance, ed. Angelo Tartuferi and Daniela Parenti, 53–58. Exh. cat. Florence: Giunti, 2006., 54. ↩︎

-

Inv. no. 1943.4.13, https://www.nga.gov/collection/art-object-page.12111.html. ↩︎

-

Inv. no. 1. ↩︎

-

Inv. no. SK-A-3976, https://www.rijksmuseum.nl/en/collection/SK-A-3976. ↩︎

-

Inv. no. 466. ↩︎

-

The present author proposed a date between 1415 and 1417, but Luciano Bellosi’s slightly later dating now seems more likely to be correct. See Laurence Kanter, in Kanter, Laurence, Barbara Drake Boehm, Carl Brandon Strehlke, Gaudenz Freuler, Christa C. Mayer Thurman, and Pia Palladino. Painting and Illumination in Early Renaissance Florence, 1300–1450. Exh cat. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1994., 252; and Bellosi, Luciano. “Lorenzo Monaco: The Later Years.” In Lorenzo Monaco: A Bridge from Giotto’s Heritage to the Renaissance, ed. Angelo Tartuferi and Daniela Parenti, 45–52. Exh. cat. Florence: Giunti, 2006., 47. ↩︎

-

See Magnolia Scudieri, in Tartuferi, Angelo, and Daniela Parenti, eds. Lorenzo Monaco: A Bridge from Giotto’s Heritage to the Renaissance. Exh. cat. Florence: Giunti, 2006., 232–36, with a summary of related opinions. ↩︎

-

Carl Strehlke, cited in Kanter, Laurence, and Pia Palladino, eds. Fra Angelico. Exh. cat. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2005., 87n10. ↩︎

-

Inv. no. 157. For the National Gallery of Art painting, see note 8, above. The original function of that painting is unknown. Miklós Boskovits speculates that it might have been the center panel of an altarpiece, but this seems unlikely; see Boskovits, Miklós. Italian Paintings of the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries. Washington, D.C.: National Gallery of Art, 2016. NGA Online Editions, https://purl.org/nga/collection/catalogue/italian-paintings-of-the-thirteenth-and-fourteenth-centuries., 235–41. ↩︎

-

Inv. no. 428. ↩︎

-

Inv. no. RF 965, https://collections.louvre.fr/en/ark:/53355/cl010062623. ↩︎

-

Seymour, Charles, Jr. Early Italian Paintings in the Yale University Art Gallery. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1970., 164. ↩︎