Chapel of Saints James and John the Baptist, Santa Maria degli Angeli, Florence, until 1799/1808; private collection, France; sale, Jean-Mar Delvaux, Paris, June 30, 2010; Richard L. Feigen (1930–2021), New York

The panel, of a horizontal wood grain, is 1.2 centimeters thick and has not been thinned in modern times. The reverse displays numerous open worm channels, but these may result from the wood having been in direct contact with another panel in its original placement at the base of an altarpiece pilaster. Nails securing the frame moldings to the panel support all end just shy of the present depth of the panel, and none has been cut. An inscription in black ink across the top of the reverse—“di Fra Filippo Lippi / pittore Fiorentino / 1450”—is written in the style of, and in a script resembling, the inscriptions added by Alfonso Tacoli Cannaci to paintings in his collection at the end of the eighteenth century.1 Three dowel holes set 2 centimeters from the right edge (viewed from the reverse) and 2, 18.5, and 35.5 centimeters from the bottom edge once secured the panel to the return face of the pilaster base—a panel showing the Baptism of Christ, now in the National Gallery, London (see fig. 4). The engaged framing elements are 1.2 centimeters thick and original, although their surfaces, except at the upper left, have been extensively repaired and locally regilt. Capping strips at the top (1.5 centimeters wide) and bottom (1.8 centimeters wide) of the frame appear also to be original. Similar capping strips, 1 centimeter wide, at the left and right edges may instead be repairs but are made of old wood. Two knots visible on the reverse of the panel, one 4 centimeters from the left edge and 20 centimeters from the bottom and the other 11 centimeters from the left edge and 14 centimeters from the bottom, have provoked no losses of paint or gilding on the picture surface, where discreet local losses of gilding along the craquelure have been repaired, most noticeably around the face of the kneeling figure in blue robes. Retouching in the right sleeve of the rose-colored cloak of the figure at the right and in the faces of the three young men behind him is more extensive than the losses they compensate.

This recently discovered panel completes the reconstruction of one of the most elaborate and artistically remarkable altarpieces commissioned for Santa Maria degli Angeli in Florence in the fourteenth century, an altarpiece described hyperbolically by Giuseppe Richa in 1759 as the most beautiful he had ever seen.2 It portrays Bernardo di Cino Bartolini Benvenuti de’ Nobili—a wealthy financier and favorite of King Charles V (from whom the entitlement to add “de’ Nobili” to his surname was procured) and King Charles VI of France—kneeling in adoration with four of his sons. The identification of the sons is not straightforward, as Bernardo de’ Nobili had five, not four, male offspring: Bartolomeo, Alamanno, Giovanni, Carlo, and Benedetto, the latter of whom may have been only two or three years old at the time this portrait was made.3 The altarpiece beneath which it stood was painted for the chapel of Saints James and John the Baptist Beheaded (San Giovanni Decollato) in the west cloister of the monastery of Santa Maria degli Angeli, founded on July 25, 1387, by Bernardo di Cino Bartolini Benvenuti de’ Nobili. The first mass was said in the chapel on March 29, 1388, by which date it may be presumed the altarpiece had been finished and installed. Santa Maria degli Angeli and the Camaldolese order were suppressed by Napoleonic decree in 1808, but many of the altarpieces in the church and cloister may already have been dismantled and at least partially dispersed before that. William Young Ottley, who owned numerous fragments from the altarpieces and choir books at Santa Maria degli Angeli, had acquired them before returning to England from Italy in 1799.

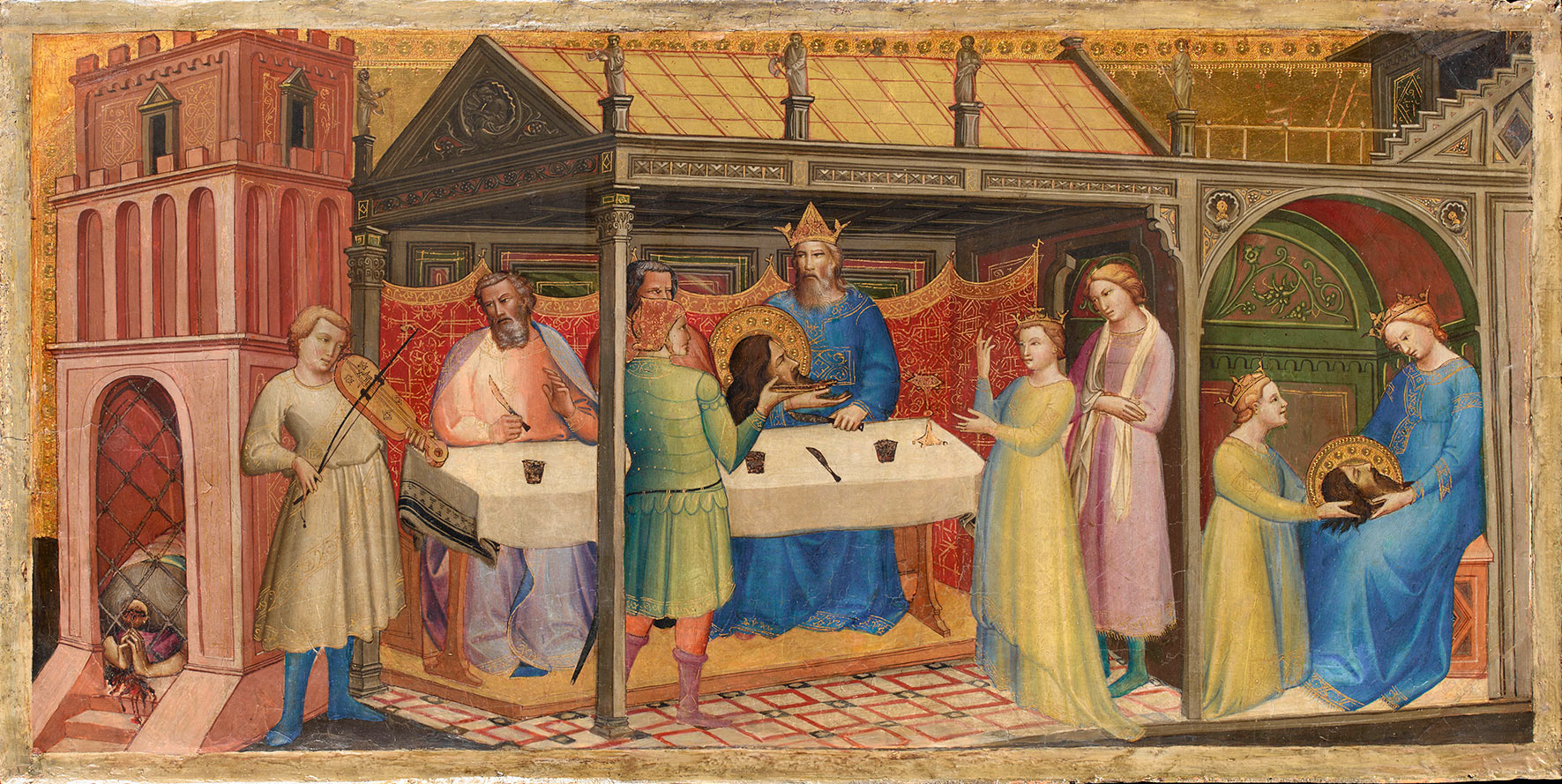

The recognition and reconstruction of the dispersed fragments of the Nobili altarpiece began in 1950, when Hans Gronau attributed three predella panels in the Musée du Louvre, Paris, to Lorenzo Monaco as his earliest works, suggesting, on iconographic grounds, that they came from the chapel of Saints James and John the Baptist at Santa Maria degli Angeli.4 These portray the Beheading of the Baptist, the Banquet of Herod, and Salome presenting the head of the Baptist to Herodias (fig. 1); the Crucifixion (fig. 2); and Saint James liberating the magician Hermogenes and the Beheading of Saint James (fig. 3). In 1964 Federico Zeri extended the predella with three additional panels: a Baptism of Christ in the National Gallery, London (fig. 4) that he believed stood between the central Crucifixion in the Louvre and the scenes of the Beheading of the Baptist, which, for compositional reasons, he situated on the right side of the predella; a donor portrait showing Piera degli Albizzi (died February 17, 1387), the wife of Bernardo de’ Nobili, and four of her daughters (fig. 5), then on the art market in Milan and now in the Alana Collection, Newark, Delaware, that he placed at the right end of the predella; and an unusual scene of Hermogenes, following his conversion by Saint James, casting his books of magic into a river (fig. 6), also now in the Alana Collection, that he imagined having stood between the Crucifixion and the scenes of the Beheading of Saint James. Finally, he hypothesized the existence of a donor portrait representing Bernardo de’ Nobili and his sons—the present panel, which was not discovered until forty-five years later—that would have closed off the predella on the left.5 Zeri also suggested that as Lorenzo Monaco may have been too young to have received so prominent a commission at this date and, as his style in these panels was so heavily influenced by that of Agnolo Gaddi, it might be more fruitful to search for the rest of the altarpiece among Agnolo’s acknowledged works.

Miklós Boskovits and Bruce Cole first associated the Louvre predella and the panels added to it by Zeri with an altarpiece triptych in Berlin representing the Virgin and Child Enthroned with Saints John the Evangelist, John the Baptist, James, and Bartholomew (fig. 7), attributed by them to Agnolo Gaddi.6 This identification entailed reversing the order of the Louvre predella panels, placing the Banquet of Herod on the left and the scenes from the legend of Saint James on the right and displacing the Baptism of Christ and the Books of Magic to pilaster bases framing the predella at either end. Erling Skaug added to these reassembled panels three pinnacles showing the Blessing Redeemer and the Annunciation (fig. 8), now in the collection of the Fondazione Francesco Federico Cerruti, Turin, which he also attributed to Agnolo Gaddi. His reconstruction placed the portrait of Piera degli Albizzi and the presumed portrait of Bernardo de’ Nobili on the outer faces of the pilaster bases, but he suggested no candidates for the painted pilasters themselves.7 Finally, the present panel and eight small full-length figures of saints from the framing pilasters, now divided between the Clowes Collection at the Indianapolis Museum of Art (fig. 9) and the Gemäldegalerie, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin (fig. 10), were added by the present author in a lecture at the Fondazione Roberto Longhi in 2012 and published by Dillian Gordon in 2020.8 Kanter recognized that the horizontal wood grain of both donor portraits argued for their placement on the front face of the predella, continuous with the panels in the Louvre, moving the Baptism and the Books of Magic to the returns on the outer face beneath the pilasters. Three dowel holes along the right edge of the reverse of the portrait of Bernardo de’ Nobili demonstrate that the London Baptism of Christ was attached to it at right angles at this point.

The completed reconstruction of the Nobili altarpiece raises the question of the attribution of its various parts. It should be stated that no documentation survives naming the artist who received this commission; it is merely a presumption that this might have been Agnolo Gaddi, with whom Lorenzo Monaco would have been working as an assistant. Gronau’s recognition of the central predella panels as early works by Lorenzo Monaco has rarely been questioned; it was rejected outright only by Mirella Levi D’Ancona and Marvin Eisenberg.9 While Zeri’s observation of the role played by Agnolo Gaddi in Lorenzo Monaco’s formation led initially to the recognition of the remainder of the altarpiece, it is salutary to bear in mind his words of caution: “It is not by any means clear at what point [Agnolo Gaddi’s] own artistic personality ends, and where the band of assistants, followers, and imitators begins.”10 The pilaster saints in Indianapolis and Berlin, for example, are indistinguishable in style from the seven panels of the predella and are certainly to be recognized as autograph works by Lorenzo Monaco. The same is true, on a considerably larger scale, for the three pinnacle panels in the Fondazione Francesco Federico Cerruti, which bear only a tangential relationship to the style of Agnolo Gaddi. Easily recognizable is Lorenzo Monaco’s characteristic, incisive drawing of hands and facial features as well as his more pronounced interest in high-key color juxtapositions to emphasize highlights. As noted elsewhere in this catalogue (see Agnolo Gaddi or Lorenzo Monaco, Saints Julian, James, and Michael), Lorenzo Monaco reinforces the outer contours of draperies in pure saturated tones rather than the simple light outlines preferred by Agnolo Gaddi, and he excavates deeper folds in the fabric with more starkly contrasting shadows, again mostly in saturated tones of local color. These traits are also notable in the main panels of the triptych in Berlin. There is no reason to believe that the entire commission was not awarded to, designed, and executed by Lorenzo Monaco, graduated from (so to speak) the studio of Agnolo Gaddi rather than working within it as a journeyman assistant.11

In her discussion of the reconstruction and historical context of the Nobili altarpiece, Dillian Gordon noted that while the overall design and content of the structure are typically Florentine, there is no precedent in Italy for the group donor portraits at either end of the predella (fig. 11).12 These she associates instead with a French royal prototype, specifically an altar embroidery owned by the Duc de Berry, part of which portrayed King Charles V kneeling in prayer with his sons opposite Queen Jeanne kneeling with her daughters. This embroidery may be simply the earliest known example of a once much larger category of image, widely diffused later in art north of the Alps. It is evident that Bernardo de’ Nobili’s regular contact with the French court and with the Duc de Berry not only gave him access to such imagery but also probably inculcated a taste for reproducing it in his own family monument. Although the family portrait has no visual precedent in Tuscany, it is a literal portrayal of the words that were recorded by Stefano Rosselli in the seventeenth century as inscribed across the base of the altarpiece: “BERNARDUS CINI DI NOBILUS FECIT FIERI HANC CAPELLAM [PRO REMEDIO ANIMAE SUAE ET SUORUM] DESCENDENTIUM” (Bernardo di Cino de’ Nobili had this chapel made for the salvation of his soul and those of his descendants).13 —LK

Published References

Manni, Domenico Maria. Osservazioni istoriche sopra i sigilli antichi de’ secoli bassi. Vol. 14. Florence: n.p., 1743., 16; Richa, Giuseppe. Notizie istoriche delle chiese Fiorentine divise ne’suoi quartieri. Vol. 8, Del quartiere di S. Giovanni. Florence: Pietro Gaetano Viviani, 1759., 166; Gordon, Dillian. “The Nobili Altarpiece from S. Maria degli Angeli, Florence.” Burlington Magazine 162, no. 1402 (January 2020): 14–25., 15, 18–19; Gordon, Dillian. “The Paintings from the Early to the Late Gothic Period.” In Santa Maria degli Angeli a Firenze: Da monastero camaldolese a Biblioteca Umanistica, ed. Cristina De Benedictis, Carla Milloschi, and Guido Tigler, 188–225. Florence: Nardini, 2022., 207, 223n90

Notes

-

See also Giovanni di Bartolomeo Cristiani, Saint Lucy Enthroned with Six Angels and Rossello di Jacopo Franchi, Virgin and Child in Glory with Saint John the Baptist, Saint Peter, and Two Angels. No painting matching the description of the present work appears in the Tacoli Canacci inventories published by Buonocore, Vincenzo M. Il marchese Alfonso Tacoli-Canacci: “Onesto gentiluomo smaniante per la Pittura.” Reggio Emilia: Società Reggiana di Studi Storici, 2005., 134–305. ↩︎

-

Richa, Giuseppe. Notizie istoriche delle chiese Fiorentine divise ne’suoi quartieri. Vol. 8, Del quartiere di S. Giovanni. Florence: Pietro Gaetano Viviani, 1759., 166. ↩︎

-

For further discussion of the identities of the figures, see Gordon, Dillian. “The Nobili Altarpiece from S. Maria degli Angeli, Florence.” Burlington Magazine 162, no. 1402 (January 2020): 14–25., 19. ↩︎

-

Gronau, Hans D. “The Earliest Works of Lorenzo Monaco—II.” Burlington Magazine 92, no. 569 (August 1950): 217–24., 217–22. ↩︎

-

Zeri, Federico. “Investigations into the Early Period of Lorenzo Monaco—I.” Burlington Magazine 106, no. 741 (December 1964): 554–58., 554–58. ↩︎

-

Boskovits, Miklós. Pittura fiorentina alla vigilia del Rinascimento, 1370–1400. Florence: Edam, 1975., 133, 348; and Cole, Bruce. Agnolo Gaddi. Oxford: Clarendon, 1977., 75, 84–87. ↩︎

-

Skaug, Erling S. “Towards a Reconstruction of the Santa Maria degli Angeli Altarpiece of 1388: Agnolo Gaddi and Lorenzo Monaco?” Mitteilungen des Kunsthistorischen Instituts in Florenz 48 (2004): 245–57., 245–57. ↩︎

-

Miklós Boskovits independently suggested that the Indianapolis panels may have stood alongside the Nobili altarpiece; see Boskovits, Miklós. Italian Paintings of the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries. Washington, D.C.: National Gallery of Art, 2016. NGA Online Editions, https://purl.org/nga/collection/catalogue/italian-paintings-of-the-thirteenth-and-fourteenth-centuries., 128–29n43. ↩︎

-

D’Ancona, Mirella Levi. “Some New Attributions to Lorenzo Monaco.” Art Bulletin 40, no. 3 (September 1958): 175–91., 187n58; and Eisenberg, Marvin. Lorenzo Monaco. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1989., 3–4, 200–201. ↩︎

-

Zeri, Federico. “Investigations into the Early Period of Lorenzo Monaco—I.” Burlington Magazine 106, no. 741 (December 1964): 554–58., 558. ↩︎

-

The motif punch used to decorate the margins of the gold ground (Skaug, Erling S. Punch Marks from Giotto to Fra Angelico: Attribution, Chronology, and Workshop Relationships in Tuscan Panel Painting, with Particular Consideration to Florence, c. 1330–1430. 2 vols. Oslo: International Institute for Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works—Nordic Group, 1994., 2: no. 424) in the present panel and the London Baptism of Christ (the other two pilaster bases have been trimmed closer and have lost this decorative band) and the punch used to decorate the frame moldings (Skaug, Erling S. Punch Marks from Giotto to Fra Angelico: Attribution, Chronology, and Workshop Relationships in Tuscan Panel Painting, with Particular Consideration to Florence, c. 1330–1430. 2 vols. Oslo: International Institute for Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works—Nordic Group, 1994., 2: no. 355) of the present panel (the gilding of the frame in the London Baptism is modern) are not recorded in any other works by either Agnolo Gaddi or Lorenzo Monaco. They do appear in an altarpiece by Mariotto di Nardo in Santa Margherita a Tosina at Boselli, near Pontassieve (see Skaug, Erling S. Punch Marks from Giotto to Fra Angelico: Attribution, Chronology, and Workshop Relationships in Tuscan Panel Painting, with Particular Consideration to Florence, c. 1330–1430. 2 vols. Oslo: International Institute for Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works—Nordic Group, 1994., 1:280), but it is unclear whether that fact is consequential in identifying the source of the commission for the Nobili altarpiece or is merely an accident of the paucity of recorded comparable material from the period. ↩︎

-

Gordon, Dillian. “The Nobili Altarpiece from S. Maria degli Angeli, Florence.” Burlington Magazine 162, no. 1402 (January 2020): 14–25., 25. ↩︎

-

Stefano Rosselli, Sepoltuario Fiorentino, ovvero Descrizione delle Chiese, Cappelle, e Sepolture, Loro Armi, ed Inscrizioni della Città di Frienze e suoi Contorni, fatta da Stefano Rosselli nell’Anno 1657, Archivio di Stato di Firenze, MS 625, fols. 1324–25, no. 16; Gordon, Dillian. The Fifteenth Century Italian Paintings. National Gallery Catalogues. London: National Gallery, 2003., 197n3; and Gordon, Dillian. “The Fourteenth-Century Altars and Chapels and Their Altarpieces in the Camaldolese Monastery of Santa Maria degli Angeli in Florence: The Saving of Souls ‘More Laudabili.’” Zeitschrift für Kunstgeschichte 3 (2013): 289–314., 303n63. ↩︎