James Jackson Jarves (1818–1888), Florence, by 1859

The Madonna of Humility is painted on a panel of a vertical wood grain, 3.7 centimeters thick and not cradled, comprising three planks: a wide central plank measuring 52.5 centimeters in width flanked by two narrower lateral planks, each approximately 6 centimeters in width. Two large iron nails on each side of the panel secure the lateral planks to the central plank. The panel has been trimmed by an indeterminate but probably small amount at each side, beginning at the height of the second acanthus crocket in the framing arch and extending straight to the base. The top edge of the arch is undisturbed; the bottom edge of the panel is covered by a later capping strip made of old wood. One minor split has opened at the bottom of the panel, 24 centimeters from the left edge. Two later battens are slotted into dovetailed channels, 23.3 and 89 centimeters from the bottom, on center. The predella and pilaster bases attached to the panel across the bottom are apparently original, but they were refashioned to follow the slight convex warp of the panel and have been entirely resurfaced. The top molding, 2.7 centimeters deep, of the framing arch, including the decorative acanthus crockets, is also original but was removed and reapplied, having been regilt and provided with a new blue background. The top-center crocket and the lowest crocket on either side, directly above the capital imposts, are recarved. The spiral colonettes on both sides are modern.

The picture surface is imperfectly visible through a thick layer of old, discolored varnish and discontinuous remnants of possibly tinted glazes. The gold ground is unevenly abraded, exposing the bolus underlayer, especially near the periphery of the arched top. Two damages—to the left of the Virgin’s halo and at the right edge of the Christ Child’s halo—have been repaired, and a split above the Child’s halo, 16 centimeters from the right edge and not visible on the reverse, interrupts the gilded surface. Surface irregularities, 63.5 centimeters from the bottom on the right (near the Virgin’s hand) and left (at the Virgin’s shoulder), could indicate the presence of nail heads securing a batten or hinges, but no evidence of nails is visible on the reverse. Similarly, a line of damages across the width of the panel, 15 centimeters from the bottom, could be the result of nail heads, but nothing is visible at that level on the reverse. The red of the Virgin’s dress is heavily abraded, in some areas exposing the gesso ground, which reads confusingly as highlights. The blue of the Virgin’s robe has been extensively retouched. The faces of both figures are relatively well preserved, although flesh tones, especially in the Child’s torso, have been abraded and inpainted around flaking losses. The Child’s feet and the Virgin’s left hand are well preserved, as is the red paint and sgraffito decoration of the cushion on which the Virgin is seated.

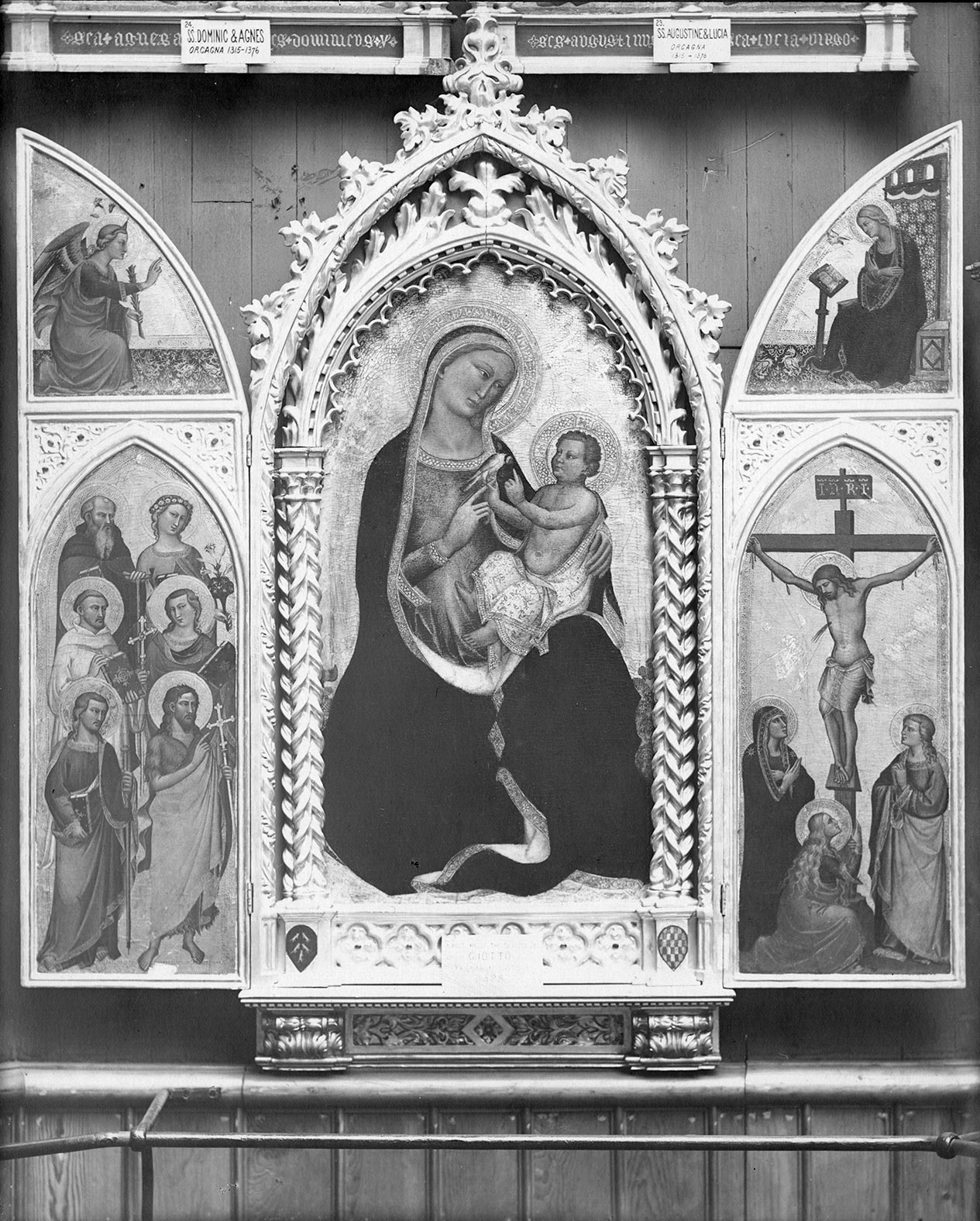

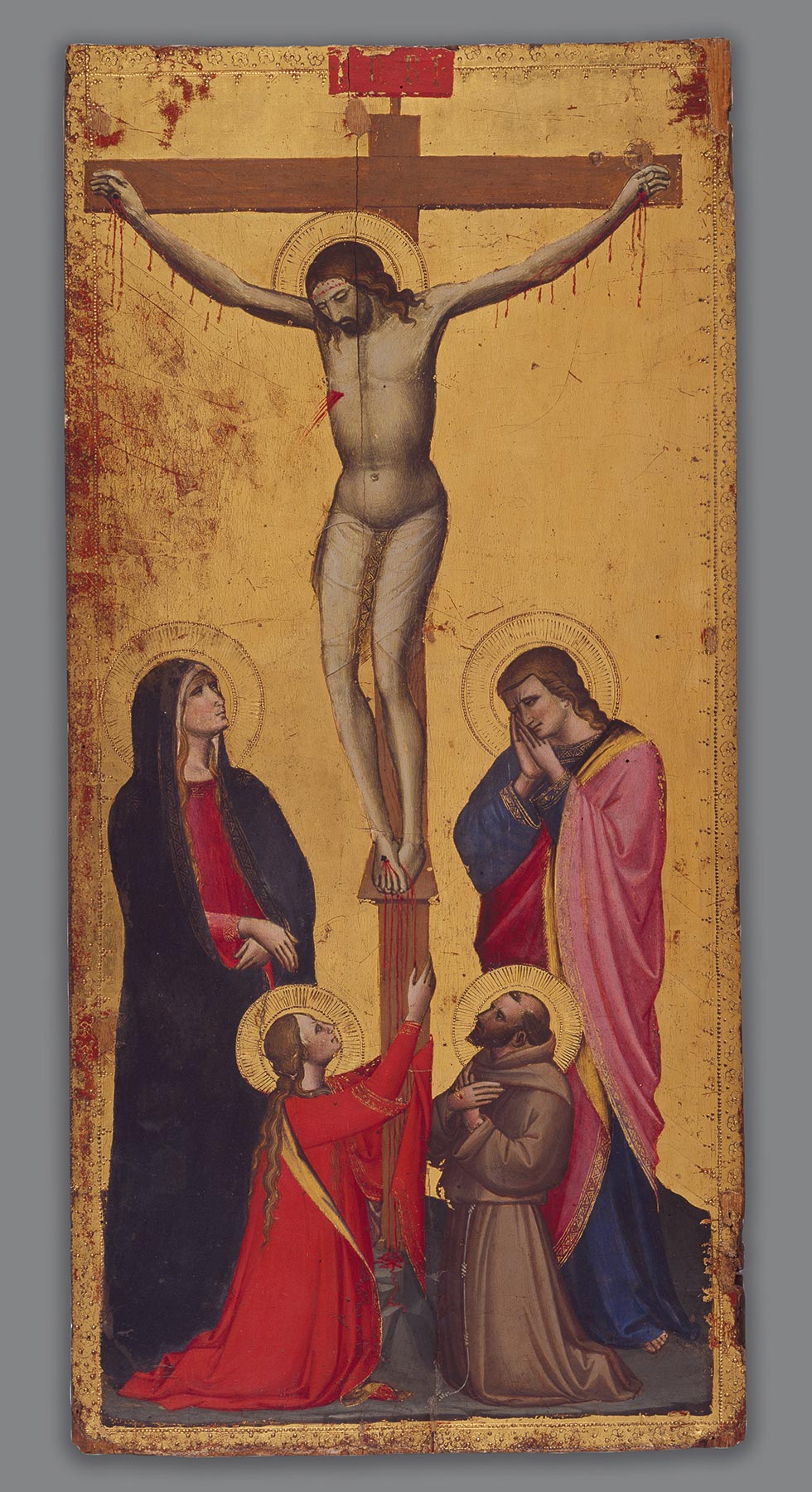

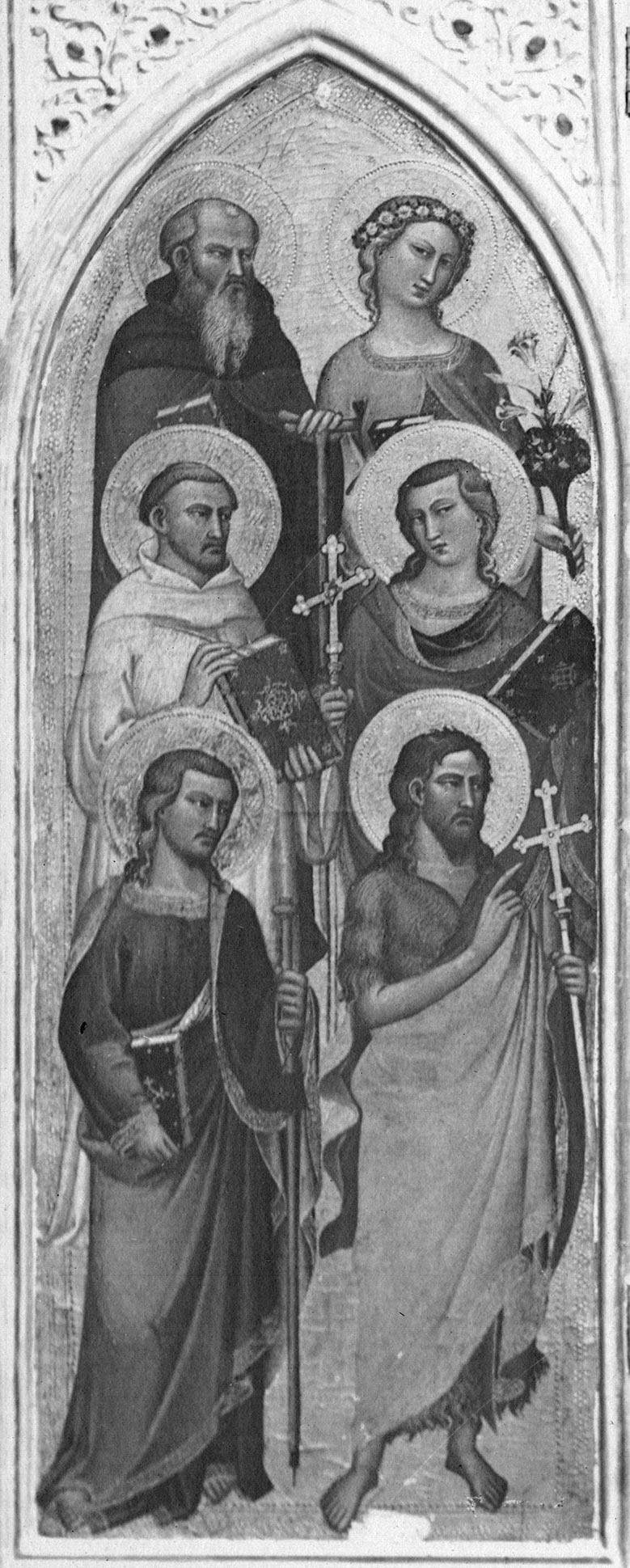

This panel and the related Crucifixion; Virgin Annunciate and Six Saints; Annunciatory Angel, presently displayed as three separate elements, were formerly joined together into a tabernacle with folding wings, first described in the 1860 catalogue of the James Jackson Jarves collection as “a magnificent triptych, uncommon from its size and condition, with the arms of the noble Vecchietti Family of Florence, now extinct” (fig. 1).1 In the center was the Madonna of Humility, shown seated on a bright-red cushion, now partly obscured by the spiral colonettes that were added at a later date. The Christ Child points to a goldfinch perched on her finger, a traditional gesture indicating His foreknowledge of the Passion and Crucifixion. The inner arch enclosing the figures as well as the pilaster bases and predella are original, as are the coats of arms: on the left base, of the Vecchietti of Florence (azure with five silver ermines); on the right, of the Ciuffagni of Florence (checkered gold and red). Sometime in the nineteenth century, the two shutters were attached by modern hinges—replacing the original metal strap ones—to a new outer frame enclosing the panel of the Virgin and Child. On the left was the wing with three pairs of standing saints, arranged on different planes to fill the vertical field: Saints James the Greater and John the Baptist in the foreground, followed by Saints Bernard of Clairvaux and Philip the Apostle (often incorrectly identified as John the Evangelist), and then Saints Anthony Abbot and Dorothy. In the compartment above them is the Annunciatory Angel. On the right was the Crucifixion with Mary Magdalen kneeling at the foot of the Cross and the Virgin Annunciate above.

Attributed to an unknown painter from the school of Giotto in the earliest catalogues of the Jarves collection, the triptych was first associated with Niccolò di Pietro Gerini or his shop by Osvald Sirén.2 Sirén, who emphasized the “coarse and clumsy” qualities of the Virgin, nevertheless considered it “among the best works produced in Gerini’s studio” and compared it specifically to a group of images by a presumed assistant of the artist, since viewed as products of Gerini’s late career: the Virgin and Child on the high altar of Santa Croce, Florence; the dated 1404 triptych in the Galleria dell’Accademia, Florence (fig. 2); and the Assumption of the Virgin triptych now in the church of San Francesco, Arezzo. In the 1916 catalogue of the Jarves Collection at Yale, Sirén revised his opinion, however, and assigned the present work to Lorenzo di Niccolò—a painter then thought to be the son and pupil of Gerini.3 Since then, the attribution of the tabernacle and its individual components has shifted between Gerini, Lorenzo di Niccolò, and Spinello Aretino. All three artists are known to have collaborated with one another on several commissions around the turn of the fourteenth century, sometimes leading to confusion over their respective oeuvres.

Richard Offner, who inserted the Yale triptych among the paintings in Gerini’s “Immediate Following,” was the first author to draw a distinction between the execution of the Madonna of Humility and the two wings, comparing the Virgin to the “lower central compartment” of the 1375 polyptych in Santa Maria all’Impruneta (Florence) and the wings to the work of Lorenzo di Niccolò.4 While acknowledging a division of hands and accepting Gerini’s authorship of the Virgin, Bernard Berenson confined the participation of an assistant to the left wing, for which he invoked the names of both Spinello Aretino and Lorenzo di Niccolò.5 The involvement of two separate personalities was questioned by Everett Fahy in his unpublished notes on some of the Yale pictures, where he gave the whole structure to Lorenzo di Niccolò.6 This attribution was tentatively accepted by Charles Seymour, Jr., who dated the work to around 1400, noting, however, that the laterals appeared to be by a different hand than the central panel and that “there is no sure indication that the wings and the central panel were originally together.”7 The same doubts concerning the pertinence of the wings to the complex were expressed by Miklós Boskovits, who nevertheless echoed Berenson and listed the triptych as a possible joint effort between Gerini and Spinello Aretino, responsible for the left wing, and proposed a date between 1395 and 1400.8 Angelo Tartuferi9 singled out this work as evidence of the ongoing collaboration between Gerini and Spinello around the turn of the century, beyond their documented involvement in the execution of the 1401 polyptych for Santa Felicita in Florence.10 While most subsequent scholarship embraced Gerini’s authorship of the Madonna of Humility, the distinction of hands and the relationship between that panel and its laterals have remained a subject of debate. Luciano Bellosi attributed the standing saints to Lorenzo di Niccolò,11 whereas Carl Strehlke, in an unpublished checklist of the Italian paintings at Yale, assigned both wings to Spinello Aretino. In the most recent discussion of the Yale triptych, Stefan Weppelmann accepted Boskovits’s division of hands and inserted the left wing in his catalogue of Spinello’s oeuvre but categorically denied any relationship between the Yale Madonna of Humility and the two wings, proposing that the latter originally flanked a different, hitherto-unidentified panel by Gerini.12

Notwithstanding Weppelmann’s arguments to the contrary, there is no clear physical evidence that the Yale panels were not originally part of the same structure. Although recent X-ray examination has confirmed the absence of hinges on the Madonna of Humility, it is still possible, as suggested by Irma Passeri, that the three panels were connected by a different framing system, alluded to by the ambitious nineteenth-century reconstruction.13 The creation of a separate frame encasing the Madonna might imply that the panel was originally contained within some other, most likely fixed structure, like a stone or marble-and-wood tabernacle, to which the wings were attached.

Stylistically, there is no reason to question the relationship between the Virgin and Child and the right wing with the Crucifixion, both of which are consistent with Gerini’s late production around 1400. The somewhat mechanical quality of the Virgin and the robust, curly-haired Christ Child bear close comparison, as observed by Sirén, to the 1404 altarpiece in the Accademia (see fig. 2) but also show analogies with the slightly earlier Virgin and Child between Saints John the Baptist and Zenobius in the same museum, most recently dated between 1395 and 1400,14 suggesting a chronology between these two works. Similarly, the Yale Crucifixion takes its place among other small images of the Crucified Christ between standing mourners by Gerini, such as the iconographically related wing fragment in the Kunstmuseum, Bern, Switzerland (fig. 3), nor is it far removed from the artist’s Crucifixion fresco in the Migliorati Chapel in San Francesco, Prato, generally placed around 1400.

Although the two wings are clearly part of the same original complex, as evidenced by their identical size, punch marks, and decorative elements, the standing saints in the left wing—whose original appearance can be gauged from photographs preceding the panels’ “cleaning” (fig. 4)—have less in common with Gerini’s dour approach than with Spinello Aretino’s essentially decorative, late Gothic sensibility. While Weppelmann compared the Yale figures to those in Spinello’s frescoes in the sacristy of Santa Croce, executed in collaboration with Gerini, more compelling analogies may be found in the slightly later banner for the Confraternity of Saint Mary Magdalen in Borgo Sansepolcro (fig. 5). This work, inserted by Boskovits into the same phase of Spinello’s activity as the Yale panels, between 1395 and 1400,15 provides close comparisons for some of the saints’ facial types. The playfully smiling angels surrounding Mary Magdalen in the banner are immediately recognizable in the features of the Yale Saints Dorothy and Philip, who also share the same coy glances and tilted heads.

The contemporary date of execution of the three panels and the documented association between Gerini and Spinello around 1400, while not conclusive evidence, strongly bolster the notion of their inclusion in the same unit. The size and complexity of the proposed tabernacle structure point to a family altar or funerary chapel inside a church or monastic setting, presumably located in Florence or its surrounding region, judging from the arms of the Vecchietti and Ciuffagni below the Madonna of Humility. The Vecchietti, whose arms appear on the left, the heraldic side usually reserved for the groom, were among the oldest and most prominent Florentine families—their social position and political influence, as well as sober lifestyle, highlighted by contemporary sources, beginning with Dante (Divine Comedy, Paradise 15.115–17). Since at least the thirteenth century, they held the patronage of the collegiate church of San Donato, also known as San Donato dei Vecchietti, in the quartiere of Santa Maria Novella.16 A provenance from San Donato dei Vecchietti is doubtful, however, given the absence of a representation of the bishop-saint Donatus in any of the panels. But one cannot exclude another religious establishment with ties to the Vecchietti, whose territorial possessions extended beyond the walls of the city. It is conceivable, on the other hand, that the tabernacle was commissioned by a member of the bride’s family, the Ciuffagni. Less renowned than the Vecchietti but equally distinguished, the Ciuffagni were one of the preeminent merchant families residing in the parish of the Cistercian church and monastery of San Frediano, in the quartiere of Santo Spirito.17 While the choice of saints in the left wing—none of whom are accorded special prominence—may simply allude to the names of one or both patrons, the inclusion of Saint Bernard of Clairvaux could reflect the Ciuffagni family’s connection to San Frediano and the Cistercian order. The elaborate tabernacle might have been commissioned by the wealthy Ciuffagni widow of a Vecchietti to decorate a chapel in San Frediano or in another, possibly female, religious establishment affiliated with the Cistercian order. Based on the inclusion of the Magdalen at the foot of the Cross in the image of the Crucifixion, Weppelmann—who discussed only the two wings—proposed a provenance from Santa Maria Maddalena in Borgo Pinti, a community of penitential nuns (convertite), who at this date were under the jurisdiction of the Badia of San Salvatore a Settimo, the most important Cistercian foundation in Florence.18 With some qualifications, this hypothesis remains valid.19 —PP

Published References

Jarves, James Jackson. Descriptive Catalogue of “Old Masters” Collected by James J. Jarves to Illustrate the History of Painting from A.D. 1200 to the Best Periods of Italian Art. Cambridge, Mass.: H. O. Houghton, 1860., 43, no. 18; Jarves, James Jackson. Art Studies: The “Old Masters” of Italy; Painting. New York: Derby and Jackson, 1861., opp. p. 181, pl. D, fig. 12; Sturgis, Russell, Jr. Manual of the Jarves Collection of Early Italian Pictures. New Haven: Yale College, 1868., 34–35, no. 22; W. F. Brown, Boston. Catalogue of the Jarves Collection of Early Italian Pictures. Sale cat. November 9, 1871., 15, no. 22; Rankin, William. “Some Early Italian Pictures in the Jarves Collection of the Yale School of Fine Arts at New Haven.” American Journal of Archaeology 10, no. 2 (April–June 1895): 137–51., 142; Rankin, William. Notes on the Collections of Old Masters at Yale University, the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, the Fogg Museum of Harvard University. Wellesley, Mass.: Department of Art, Wellesley College, 1905., 8, no. 22; Sirén, Osvald. “Trecento Pictures in American Collections—II.” Burlington Magazine 14, no. 69 (December 1908): 188–94., 194, pl. 3, no. 2; Sirén, Osvald. A Descriptive Catalogue of the Pictures in the Jarves Collection Belonging to Yale University. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1916., 71–72, no. 26; Offner, Richard. “Niccolò di Pietro Gerini, Part Two.” Art in America 9, no. 6 (October 1921): 233–40., 239; van Marle, Raimond. The Development of the Italian Schools of Painting. Vol. 3. The Hague: M. Nijhoff, 1924., 643; Berenson, Bernard. Italian Pictures of the Renaissance: A List of the Principal Artists and Their Works with an Index of Places. Oxford: Clarendon, 1932., 303, 396; Berenson, Bernard. Italian Pictures of the Renaissance, A List of the Principal Artists and Their Works with an Index of Places: The Florentine School. 2 vols. London: Phaidon, 1963., 1:160; Klesse, Brigitte. Seidenstoffe in der italienischen Malerei des 14. Jahrhunderts. Bern, Switzerland: Stämpfli, 1967., 319, no. 244a; Seymour, Charles, Jr. Early Italian Paintings in the Yale University Art Gallery. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1970., 52–54, nos. 36a–c; Fredericksen, Burton B., and Federico Zeri. Census of Pre-Nineteenth-Century Italian Paintings in North American Public Collections. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1972., 81, 599; Boskovits, Miklós. Pittura fiorentina alla vigilia del Rinascimento, 1370–1400. Florence: Edam, 1975., 411, 438–39; Offner, Richard. A Critical and Historical Corpus of Florentine Painting: The Fourteenth Century. Supplement: A Legacy of Attributions. Ed. Hayden B. J. Maginnis. New York: Institute of Fine Arts, New York University, 1981., 83; Tartuferi, Angelo. “Spinello Aretino in San Michele Visdomini a Firenze (e alcune osservazioni su Lorenzo di Niccolò).” Paragone 34, no. 395 (1983): 3–18., 8, 18n34; Weppelmann, Stefan. Spinello Aretino e la pittura del trecento in Toscana. Florence: Polistampa, 2011., 267–69, no. 60

Notes

-

Jarves, James Jackson. Descriptive Catalogue of “Old Masters” Collected by James J. Jarves to Illustrate the History of Painting from A.D. 1200 to the Best Periods of Italian Art. Cambridge, Mass.: H. O. Houghton, 1860., 43, no. 18. ↩︎

-

Sirén, Osvald. “Trecento Pictures in American Collections—II.” Burlington Magazine 14, no. 69 (December 1908): 188–94., 194, pl. 3, no. 2. ↩︎

-

Sirén, Osvald. A Descriptive Catalogue of the Pictures in the Jarves Collection Belonging to Yale University. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1916., 71–72, no. 26. ↩︎

-

Offner, Richard. “Niccolò di Pietro Gerini, Part Two.” Art in America 9, no. 6 (October 1921): 233–40., 239. ↩︎

-

In the 1932 edition of his lists, Berenson listed the triptych under Gerini’s name, specifying that the Virgin and the right wing with the Crucifixion were by Gerini, while the left wing was “by Spinello Aretino with assistance of Lorenzo di Niccolò.” However, in the same volume, he did not mention Spinello’s participation when listing the wing under Lorenzo di Niccolò and did not include it with Spinello’s oeuvre, possibly implying a change of opinion during the writing of the text; see Berenson, Bernard. Italian Pictures of the Renaissance: A List of the Principal Artists and Their Works with an Index of Places. Oxford: Clarendon, 1932., 303, 396. In the 1963 edition, Lorenzo di Niccolò is listed as the author of the left wing and sole collaborator of Gerini in the execution of the triptych; see Berenson, Bernard. Italian Pictures of the Renaissance, A List of the Principal Artists and Their Works with an Index of Places: The Florentine School. 2 vols. London: Phaidon, 1963., 1:160. ↩︎

-

Unpublished notes, ca. 1965, curatorial files, Department of European Art, Yale University Art Gallery. ↩︎

-

Seymour, Charles, Jr. Early Italian Paintings in the Yale University Art Gallery. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1970., 53. ↩︎

-

Boskovits, Miklós. Pittura fiorentina alla vigilia del Rinascimento, 1370–1400. Florence: Edam, 1975., 411, 438–39. ↩︎

-

Tartuferi, Angelo. “Spinello Aretino in San Michele Visdomini a Firenze (e alcune osservazioni su Lorenzo di Niccolò).” Paragone 34, no. 395 (1983): 3–18., 8, 18n34. ↩︎

-

Galleria dell’Accademia, Florence, inv. no. 1890 n. 8468. ↩︎

-

Verbal communication, 1987, recorded in the curatorial files, Department of European Art, Yale University Art Gallery. ↩︎

-

Weppelmann, Stefan. Spinello Aretino e la pittura del trecento in Toscana. Florence: Polistampa, 2011., 267–69, no. 60. ↩︎

-

Irma Passeri, written communication to Laurence Kanter, July 6, 2021. ↩︎

-

Galleria dell’Accademia, Florence, inv. no. 1890 n. 439; Federica Baldini, in Boskovits, Miklós, and Daniela Parenti, eds. Cataloghi della Galleria dell’Accademia di Firenze: Dipinti. Vol. 2, Il tardo trecento. Florence: Giunti, 2010., 132–35, no. 25. ↩︎

-

Boskovits, Miklós. Pittura fiorentina alla vigilia del Rinascimento, 1370–1400. Florence: Edam, 1975., 439. ↩︎

-

See D’Addario, Arnaldo. “Vecchietti.” Enciclopedia Dantesca (1970), https://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/vecchietti_(Enciclopedia-Dantesca)/.. For the church of San Donato dei Vecchietti, demolished in the nineteenth century, see Richa, Giuseppe. Notizie istoriche delle chiese fiorentine divise ne’suoi quartieri. Vol. 4, Del quartiere di Santa Maria Novella: Parte seconda. Florence: Pietro Gaetano Viviani, 1756., 159–67. ↩︎

-

Porta Casucci, Emanuela. “Le paci fra private nelle parrocchie fiorentine di S. Felice in Piazza e S. Frediano: Un regesto per gli anni 1335–1365.” Annali di storia di Firenze 4 (2009): 195–241., 235–36n25. ↩︎

-

In 1321 some of the Cistercian nuns from San Donato a Torri in Polverosa, outside Florence, were sent to join the nuns from Santa Maria Maddalena, who then took on the Cistercian habit. See Richa, Giuseppe. Notizie istoriche delle chiese fiorentine divise ne’suoi quartieri. Vol. 1, Del quartiere di Santa Croce: Parte prima. Florence: Pietro Gaetano Viviani, 1754., 300–313; and Repetti, Emanuele. “San Donato in Polverosa.” In Dizionario geografico fisico storico della Toscana. Florence: n.p., 1843., 544–45. ↩︎

-

It is puzzling that Weppelmann (in Weppelmann, Stefan. Spinello Aretino e la pittura del trecento in Toscana. Florence: Polistampa, 2011., 269) should cite the well-known Carmelite church of Santa Maria del Carmine as one of the “principal” Cistercian monasteries in Florence, neglecting to mention San Frediano or the Badia a Settimo, the first foundations of the order in the city. His assertion that the light-colored cloak worn by Saint John the Baptist relates to the white habit of the Cistercian order is also without foundation. ↩︎