James Jackson Jarves (1818–1888), Florence, by 1859

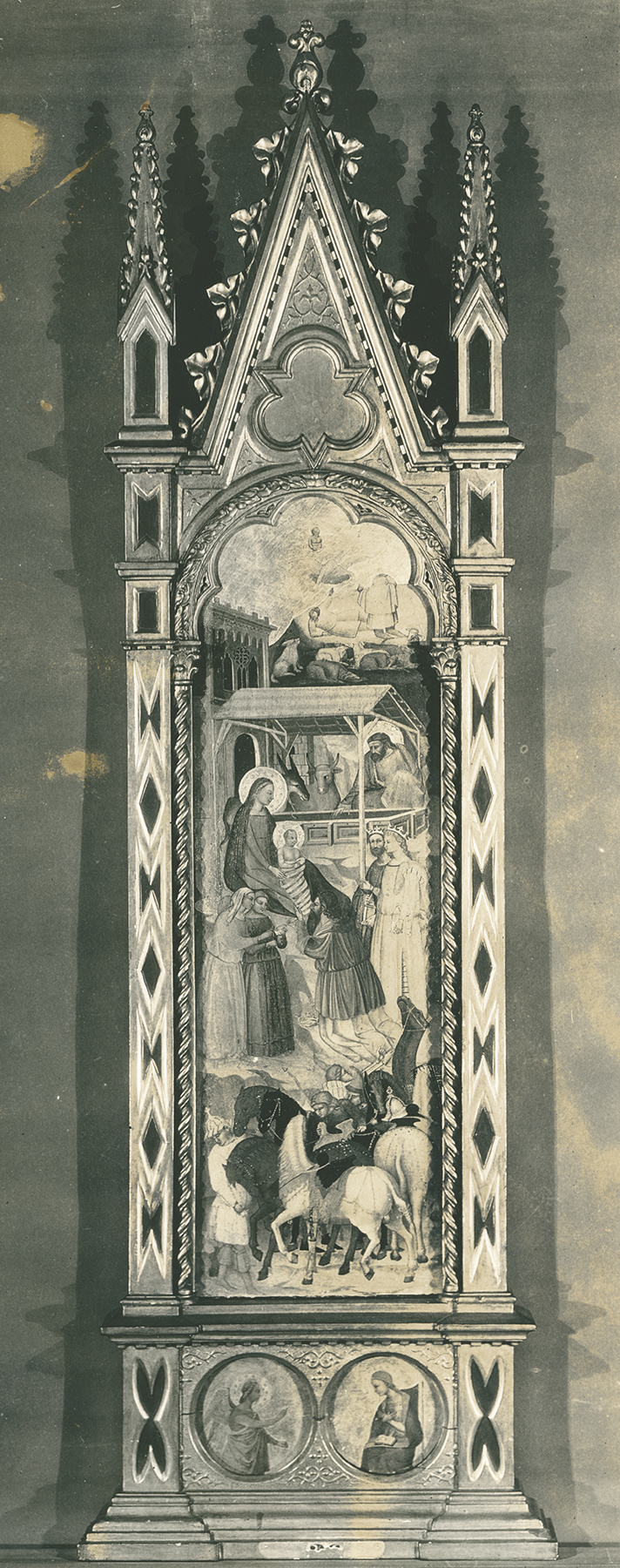

The Adoration of the Magi is painted on a panel with a vertical grain, thinned to a depth of 1.4 centimeters but not cradled. A channel 3 centimeters wide at the bottom of the panel on the reverse has been thinned to half this depth, as if to receive a strap hinge, but there is no evidence of nails in that area and no evidence of other types of hinges at either side. The panel has been cut on all four sides, although an engraved line along the left margin may indicate the original extent of the painted scene on that side. The paint surface is relatively well preserved but has been lightly abraded overall. The gilding, except in the haloes of the Holy Family, has been almost entirely lost. When the panel entered the James Jackson Jarves collection (fig. 1), the upper portion had been newly (i.e., in the nineteenth century) gilt to the full, rounded profile of the panel. This was removed by Andrew Petryn in 1968, leaving only a small island of bolus with traces of original gilding around the figures of the angel and the Child at the top. The rest was scraped down: at the right, to a polished gesso layer outlining the profile of an ogival arch and, at the left, to exposed linen and wood (fig. 2). In a cleaning and restoration of 1998, Elisabeth Mention covered the exposed gesso and completed the ogival arch with a painted bolus color. Flaking losses that had been revealed in the 1968 restoration, chiefly around the perimeter of the scene, were inpainted or, along the right edge of the composition, gilded, although reasons for gilding that side are unclear. The faces of the retainers at the bottom, except for the figure furthest to the left, have been restored, as have the faces of the two standing Magi and the Christ Child. Small losses in the draperies of Saint Joseph have been repaired and complete areas of loss approximately 6 centimeters long at the spring of the arch on both sides have been filled with freely invented painted details. The modeling on the head and neck of the camel at the lower right is also an invention of the 1998 restoration.

This Adoration of the Magi, along with a roundel showing the Virgin Annunciate and another with an Annunciatory Angel, are fragments of the same unidentified complex. When they were in the Jarves collection, they were displayed in a nineteenth-century frame, with the roundels of the Annunciation placed below the Adoration of the Magi as elements of a predella (fig. 3). The size and proportions of the Adoration, however, suggest that it was originally the left wing of a folding triptych and that the small roundels probably occupied the spandrels of the central panel or the gables of the lateral ones. The original appearance of the Annunciatory Angel and the Virgin Annunciate is difficult to ascertain in their present state, but the drawing of the figures and identical tooling and punching in the haloes confirm their association with the Adoration of the Magi.

Notwithstanding its abraded condition—and elimination of most of the gilt surfaces—the Adoration still manages to retain the original charming effect produced by the sheer variety of anecdotal details and figural types, which the artist has succeeded in compressing into the limited, narrow format. The composition combines elements of the Nativity and Adoration of the Magi and is organized vertically on different levels of the rocky landscape, which acts as both a backdrop and an anchor for the spatial arrangement. In the lowest zone, at the base of the panel, is a lively group of elegantly saddled horses and brightly clad attendants, one of whom struggles to restrain a frightened camel. In the middle ground is the main event, dominated by the large shed of the Nativity projecting from the facade of a Gothic building. Careful attention has been devoted to the architectural components of these two structures, as well as to the rendering of realistic details, such as the knotted cord threaded through holes in the wood by which the ass and ox are tethered to the manger. Disposed on different planes under the roof of the shed are the Virgin and Child, seated on a rocky outcrop, and Joseph, crouched alongside the animals behind the manger. Kneeling on a steep incline below the Virgin is one of the Magi, who kisses the Child’s feet in adoration. On the same plane as the Magi are two female attendants, presumably midwives, curiously examining the contents of the king’s gift. In the uppermost section of the composition, on the mountain’s summit, is the Annunciation to the Shepherds. Both figures are bathed in the brilliant aura of the angel; one of them is on his knees, shielding his eyes from the light, while the other, in a reclined position, has just been awakened from his sleep. Directly above the angel, centered under the panel’s pointed arch, is a diminutive Christ Child emerging from a cloud instead of the more typical representation of God the Father. The motif, relatively rare in fourteenth-century panel painting, is usually associated with images of the Annunciation to the Virgin and, more often than not, appears in a Franciscan context.1 The nearest equivalent for the present example is Taddeo Gaddi’s fresco in the Baroncelli Chapel in Santa Croce, Florence (fig. 4), which shows a small Christ Child bathed in golden light appearing to the Magi, as described in the Golden Legend accounts of both the Nativity and Epiphany: “Then there are the luminous corporeal creatures, such as the supercelestial: these too revealed the Nativity. For on that very day, according to what the ancients relate and Chrysostom affirms, the magi were praying on a mountaintop and a star appeared above them. This star had the shape of a most beautiful boy over whose head a cross shone brilliantly.”2

The Adoration of the Magi, which entered Yale’s collection with an attribution to Simone Martini, was identified as a product of the Florentine school by William Rankin, who classified it somewhat cryptically as “Spinellesque Style of Early Bicci Class,” noting that it reflected the influence of “Sienese decorative and technical ideals” upon Florentine painting.3 Osvald Sirén, who highlighted the painting’s “remarkably fine” execution and naturalistically observed details, first advanced the name of Orcagna, proposing a date in close proximity to the Strozzi Altarpiece, between 1350 and 1360.4 While acknowledging the Orcagnesque quality of the figures, Raimond van Marle subsequently inserted the panel among a group of works he ascribed to an anonymous collaborator of Andrea di Cione, christened “compagno dell’Orcagna”—otherwise identified as Nardo di Cione.5 In his 1927 catalogue of Yale’s collection, Richard Offner gave a much less enthusiastic assessment of the painting, stating that it bore “only the slenderest relation” to either Orcagna or Nardo di Cione but was more likely the effort of an anonymous imitator; he labeled the image generically as “Florentine Painter (End of the Fourteenth-Century).”6 In subsequent references to the Adoration, however, Offner also referred to the panel as “Cionesque”7 or filed it under “Yale Orcagnesque Master,”8 without identifying any other works by the same hand. Bernard Berenson initially placed the Adoration in his category of “Florentine Giottesque Painters after 1350,”9 later broadened to “Unidentified Florentines, ca. 1350–1420,”10 in both instances qualifying its style as “between Jacopo di Cione and Antonio Veneziano.” The narrative and spatial solutions of the Yale Adoration did not go unnoticed by Luigi Coletti, however, who cited the panel in his discussion of the Maso-Giottino problem, tentatively advancing a comparison with the Crucifixion in the Musée du Louvre, Paris, currently attributed to Giotto’s Neapolitan workshop.11

In 1968, in a fundamental article dedicated to the then-still-obscure personality of Cenni di Francesco, Miklós Boskovits first inserted the Yale Adoration into the artist’s oeuvre, placing its execution around 1390, a chronology that he later revised to 1380–85.12 Boskovits’s study was overlooked by Charles Seymour, Jr., who catalogued the panel generically as Florentine school with a date between 1395 and 1400.13 However, the attribution to Cenni di Francesco is convincing and has been otherwise embraced by modern scholarship. Among the works most closely related to the Adoration are those images formerly grouped around the Saint Catherine Disputing and Two Donors in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (fig. 5), which is usually dated around 1380.14 Once regarded as efforts of an anonymous Orcagnesque painter named “Master of the Kahn Saint Catherine” (after the early owner of the Metropolitan Museum panel), these works are now generally acknowledged as products of Cenni’s earlier career, when he was still under the strong influence of Giovanni del Biondo. Typical of the artist’s approach at this moment are the rigidly posed, solid physiognomic types, with the long necks and small heads that also distinguish the Yale picture. The beautifully preserved panel of Saint Catherine, in particular, presents an almost identical decorative vocabulary and provides a hint of the coloristic brilliance and precious handling of ornamental features that must originally have characterized the Adoration.

Compositionally, the Yale panel is intimately related to Cenni’s dated 1383 fresco of the Adoration of the Magi in the church of San Donato in Polverosa, Florence (fig. 6). Notwithstanding the differences in scale, the works share the same piecemeal approach to the various elements of the narrative, similarly staged against a rocky backdrop. Some of the more unusual anecdotal details of the Yale image, like the two female attendants examining the Magi’s gift, are also included in the fresco, as are other subsidiary figures, such as the identically posed attendant in a yellow cape with black and red stripes, struggling with the recalcitrant camel. The rounder proportions and generally more dynamic movement of the figures and draperies in the fresco, however, suggest a slightly more advanced date of execution. The miniaturist quality that has sometimes been highlighted in past discussions of the Yale Adoration seems consistent with Cenni’s activity as a manuscript illuminator between the 1370s and 1380s.15 Closely related to the present work are the artist’s illuminations in an antiphonary in the Walters Art Gallery, Baltimore, usually placed before the San Donato in Polverosa commission.16

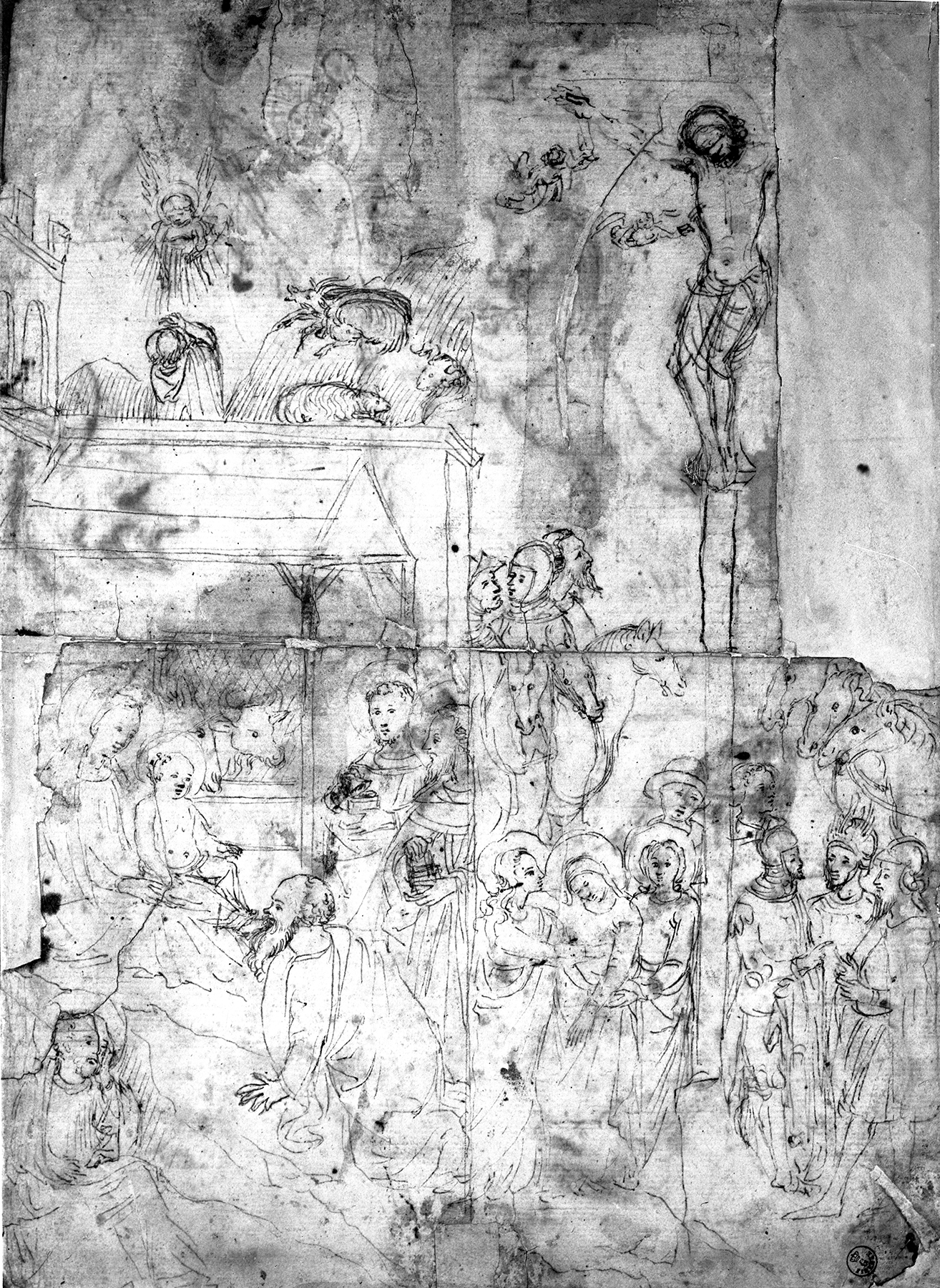

While it has not been possible to identify other elements from the same complex, a clue to the subject matter and appearance of the missing right wing of Cenni’s triptych is contained in a little-known fourteenth-century sheet of drawings in the Gallerie degli Uffizi, Florence (fig. 7). The sheet was first cited as comparison for the Adoration of the Magi by Jarves, who noted that the drawing for the “upper portion” of the picture was preserved “among the designs of the old master in the Florentine Gallery.”17 Jarves’s reference, recorded in the next two catalogues of his collection18 but overlooked or dismissed by all subsequent scholarship, is especially relevant since the sheet in question, divided along its length into two equal sections, appears, in fact, to be a sketch of the two wings of a triptych.19 On the left side is a compressed version of the Yale composition, showing the Adoration and the Annunciation to the Shepherds in the same narrow, vertical format against a rocky backdrop. Missing from the drawing is the bottom section of the Yale image and subsidiary details, such as the two female attendants and the Christ Child in the clouds, but the two compositions are otherwise identical in most aspects. On the right half of the Uffizi sheet is a crowded representation of the Crucifixion, suggesting that a similar composition also appeared in the right wing of Cenni’s triptych, opposite the Yale Adoration. The scene, the vertical thrust of which provides a parallel to the Adoration, is organized around the impossibly tall Cross, which takes up the entire length of the paper, with the various figures and animals arranged on different levels in the narrow space on either side. At the base of the Cross are the swooning Virgin, supported by the Magdalen and John the Evangelist, and three soldiers arguing over Christ’s clothing. Peeking out from behind the Cross is a curious figure wearing some sort of bowler hat. On a different plane, above the main characters, are six soldiers on horseback, symmetrically disposed into two sets of three each, on both sides of the Cross (the soldiers on the right are no longer visible due to a tear in the paper).

The Uffizi drawing, which like the Yale picture was ascribed by nineteenth-century scholars to Simone Martini, was identified by Luciano Bellosi as the product of an anonymous Florentine artist, possibly an illuminator, active toward the end of the fourteenth century.20 The quick pen-and-ink sketches make it difficult to advance a more precise attribution, although the liveliness of the figures, as noted by Bellosi, does recall the illustrations in a codex of Ovid’s Metamorphoses in the Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale, Florence, which have been recently dated around 1390.21 It is worth speculating whether Cenni’s triptych might have provided the very model for the drawing or if both works were inspired by a well-known prototype, possibly located in one of the major Florentine churches. The size of the Yale Adoration points to a significant structure, commissioned for either a chapel or side altar. The presence of the motif of the Christ Child in the sky, rare in images of the Adoration and perhaps derived directly from Taddeo Gaddi’s example in Santa Croce, could indicate a Franciscan commission. —PP

Published References

Jarves, James Jackson. Descriptive Catalogue of “Old Masters” Collected by James J. Jarves to Illustrate the History of Painting from A.D. 1200 to the Best Periods of Italian Art. Cambridge, Mass.: H. O. Houghton, 1860., 46, no. 36; Sturgis, Russell, Jr. Manual of the Jarves Collection of Early Italian Pictures. New Haven: Yale College, 1868., 28–29, no. 15; W. F. Brown, Boston. Catalogue of the Jarves Collection of Early Italian Pictures. Sale cat. November 9, 1871., no. 15; Rankin, William. “Some Early Italian Pictures in the Jarves Collection of the Yale School of Fine Arts at New Haven.” American Journal of Archaeology 10, no. 2 (April–June 1895): 137–51., 143; Rankin, William. Notes on the Collections of Old Masters at Yale University, the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, the Fogg Museum of Harvard University. Wellesley, Mass.: Department of Art, Wellesley College, 1905., 8, no. 15; Sirén, Osvald. “Pictures in America by Bernardo Daddi, Taddeo Gaddi, Andrea Orcagna, and His Brothers—I.” Art in America 2, no. 4 (June 1914): 263–75., 273–74, fig. 5; Sirén, Osvald. A Descriptive Catalogue of the Pictures in the Jarves Collection Belonging to Yale University. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1916., 41–42, no. 15; Sirén, Osvald. Giotto and Some of His Followers. Trans. Frederic Schenck. 2 vols. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1917., 1:227–29, 2: pl. 193; van Marle, Raimond. The Development of the Italian Schools of Painting. Vol. 3. The Hague: M. Nijhoff, 1924., 514–16; Offner, Richard. Italian Primitives at Yale University: Comments and Revisions. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1927., 17, figs. 8–8a; Berenson, Bernard. Italian Pictures of the Renaissance: A List of the Principal Artists and Their Works with an Index of Places. Oxford: Clarendon, 1932., 238; Coletti, Luigi. “Contributo al problema Maso-Giottino.” Emporium 96 (1942): 461–78., 470; Berenson, Bernard. Italian Pictures of the Renaissance, A List of the Principal Artists and Their Works with an Index of Places: The Florentine School. 2 vols. London: Phaidon, 1963., 1:215; Boskovits, Miklós. “Ein Vorläufer der spätgotischen Malerei in Florenz: Cenni di Francesco di Ser Cenni.” Zeitschrift für Kunstgeschichte 31, no. 4 (1968): 273–92., 279–89, 291n21, fig. 8; Seymour, Charles, Jr. Early Italian Paintings in the Yale University Art Gallery. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1970., 34–36, nos. 20a–c; Fredericksen, Burton B., and Federico Zeri. Census of Pre-Nineteenth-Century Italian Paintings in North American Public Collections. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1972., 599; Boskovits, Miklós. Pittura fiorentina alla vigilia del Rinascimento, 1370–1400. Florence: Edam, 1975., 290; Offner, Richard. A Critical and Historical Corpus of Florentine Painting: The Fourteenth Century. Supplement: A Legacy of Attributions. Ed. Hayden B. J. Maginnis. New York: Institute of Fine Arts, New York University, 1981., 15; Offner, Richard. A Critical and Historical Corpus of Florentine Painting: The Fourteenth Century. Sec. 3, vol. 5, Bernardo Daddi and His Circle. Ed. Miklós Boskovits. Florence: Giunti, 2001., 466n1; Alice Turchi, in Boskovits, Miklós, and Daniela Parenti, eds. Cataloghi della Galleria dell’Accademia di Firenze: Dipinti. Vol. 2, Il tardo trecento. Florence: Giunti, 2010., 28

Notes

-

The iconographic motif has been traced to the Lignum vitae of Saint Bonaventure (1221–1274), and the notion that Christ entered the Virgin’s womb fully formed. The earliest evidence of its appearance in Florentine painting is the medallion of the Annunciation in Pacino’s Tree of Life in the Galleria dell’Accademia, inv. no. 1890 n. 8459, executed for the Clarissan nuns of Monticelli in the second decade of the fourteenth century—a work that follows Bonaventure’s text to the letter; see Robb, David M. “The Iconography of the Annunciation in the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Centuries.” Art Bulletin 18 (December 1936): 480–526., 523–26, and, more recently, Brunori, Lia. “‘Ed era sì piccolino, che non era quanto una cruna d’aco’: Breve percorso iconografico nelle Annunciazioni di Giovanni dal Ponte.” In Giovanni dal Ponte: Protagonista dell’umanesimo tardogotico fiorentino, ed. Lorenzo Sbaraglio and Angelo Tartuferi, 53–61. Exh. cat. Florence: Galleria dell’Accademia, 2016., 53–61. ↩︎

-

de Voragine, Jacobus. The Golden Legend. Trans. William Granger Ryan. 2 vols. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1993., 1:40, 80. ↩︎

-

Rankin, William. Notes on the Collections of Old Masters at Yale University, the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, the Fogg Museum of Harvard University. Wellesley, Mass.: Department of Art, Wellesley College, 1905., 8, no. 15. ↩︎

-

Sirén, Osvald. “Pictures in America by Bernardo Daddi, Taddeo Gaddi, Andrea Orcagna, and His Brothers—I.” Art in America 2, no. 4 (June 1914): 263–75., 273–74, fig. 5; Sirén, Osvald. A Descriptive Catalogue of the Pictures in the Jarves Collection Belonging to Yale University. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1916., 41–42, no. 15; and Sirén, Osvald. Giotto and Some of His Followers. Trans. Frederic Schenck. 2 vols. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1917., 1:227–29, 2: pl. 193. ↩︎

-

van Marle, Raimond. The Development of the Italian Schools of Painting. Vol. 3. The Hague: M. Nijhoff, 1924., 514–16. ↩︎

-

Offner, Richard. Italian Primitives at Yale University: Comments and Revisions. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1927., 17. ↩︎

-

Offner, Richard. A Critical and Historical Corpus of Florentine Painting: The Fourteenth Century. Sec. 3, vol. 5, Bernardo Daddi and His Circle. Ed. Miklós Boskovits. Florence: Giunti, 2001., 466n1. ↩︎

-

Offner, Richard. A Critical and Historical Corpus of Florentine Painting: The Fourteenth Century. Supplement: A Legacy of Attributions. Ed. Hayden B. J. Maginnis. New York: Institute of Fine Arts, New York University, 1981., 15. ↩︎

-

Berenson, Bernard. Italian Pictures of the Renaissance: A List of the Principal Artists and Their Works with an Index of Places. Oxford: Clarendon, 1932., 238. ↩︎

-

Berenson, Bernard. Italian Pictures of the Renaissance, A List of the Principal Artists and Their Works with an Index of Places: The Florentine School. 2 vols. London: Phaidon, 1963., 1:215. ↩︎

-

Inv. no. RF 1999 11, https://collections.louvre.fr/en/ark:/53355/cl010067146; Coletti, Luigi. “Contributo al problema Maso-Giottino.” Emporium 96 (1942): 461–78., 470. ↩︎

-

Boskovits, Miklós. “Ein Vorläufer der spätgotischen Malerei in Florenz: Cenni di Francesco di Ser Cenni.” Zeitschrift für Kunstgeschichte 31, no. 4 (1968): 273–92.; and Boskovits, Miklós. Pittura fiorentina alla vigilia del Rinascimento, 1370–1400. Florence: Edam, 1975., 290. ↩︎

-

Seymour, Charles, Jr. Early Italian Paintings in the Yale University Art Gallery. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1970., 34–36, no. 20a. ↩︎

-

Laurence B. Kanter, in Kanter, Laurence, Barbara Drake Boehm, Carl Brandon Strehlke, Gaudenz Freuler, Christa C. Mayer Thurman, and Pia Palladino. Painting and Illumination in Early Renaissance Florence, 1300–1450. Exh cat. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1994., 183–86, no. 19; and Keith Christiansen, “Saint Catherine Disputing and Two Donors,” Metropolitan Museum of Art, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/435863. ↩︎

-

Boskovits, Miklós. “Ein Vorläufer der spätgotischen Malerei in Florenz: Cenni di Francesco di Ser Cenni.” Zeitschrift für Kunstgeschichte 31, no. 4 (1968): 273–92., 279–89, 291n21. ↩︎

-

Inv. no. W.153, https://art.thewalters.org/detail/13576/antiphonary-2/. For the most recent detailed discussion of the Baltimore Antiphonary, possibly executed for the church of San Pier Maggiore in Florence, see Chiodo, Sonia. A Critical and Historical Corpus of Florentine Painting. Sec. 4, vol. 9, Painters in Florence after the “Black Death”: The Master of the Misericordia and Matteo di Pacino. Ed. Miklós Boskovits. Florence: Giunti, 2011., 66–76, with previous bibliography. The division of hands among the illuminations in this volume remains the subject of some debate, mainly concerning the possible involvement of the Master of the Misericordia. Most authors, however, agree that Cenni was responsible for the illuminations on fols. 4v, 27v, and 39v. Following Boskovits, Chiodo dated the artist’s intervention between 1375 and 1380, while others have proposed a slightly later chronology, around 1380 or a bit later; see Kanter, in Kanter, Laurence, Barbara Drake Boehm, Carl Brandon Strehlke, Gaudenz Freuler, Christa C. Mayer Thurman, and Pia Palladino. Painting and Illumination in Early Renaissance Florence, 1300–1450. Exh cat. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1994., 178–83, no. 18. ↩︎

-

Jarves, James Jackson. Descriptive Catalogue of “Old Masters” Collected by James J. Jarves to Illustrate the History of Painting from A.D. 1200 to the Best Periods of Italian Art. Cambridge, Mass.: H. O. Houghton, 1860., 46, no. 36. ↩︎

-

Sturgis, Russell, Jr. Manual of the Jarves Collection of Early Italian Pictures. New Haven: Yale College, 1868., 28–29, no. 15; and W. F. Brown, Boston. Catalogue of the Jarves Collection of Early Italian Pictures. Sale cat. November 9, 1871., no. 15. ↩︎

-

Fiora Bellini, in Bellosi, Luciano, Fiora Bellini, and Giulia Brunetti. I disegni antichi degli Uffizi: I tempi del Ghiberti. Exh. cat. Florence: Leo S. Olschki, 1978., 6–7, no. 3. Spread across the reverse of the sheet are various studies of dogs, birds, and the head of a griffin. ↩︎

-

Luciano Bellosi, in Bellosi, Luciano, Fiora Bellini, and Giulia Brunetti. I disegni antichi degli Uffizi: I tempi del Ghiberti. Exh. cat. Florence: Leo S. Olschki, 1978., xvi; and Bellini, in Bellosi, Luciano, Fiora Bellini, and Giulia Brunetti. I disegni antichi degli Uffizi: I tempi del Ghiberti. Exh. cat. Florence: Leo S. Olschki, 1978., 6–7, no. 3. ↩︎

-

Inv. no. Panciatichiano, 63; Martina Bordone, in Azzetta, Luca, Sonia Chiodo, and Teresa De Robertis, eds. “An Ancient and Honourable Citizen of Florence”: The Bargello and Dante. Exh. cat. Florence: Mandragora, 2021., 262–65, no. 42. Bordone identified two separate hands in the decoration of the volume and cautiously proposed that the more accomplished artist might be Gherardo Starnina, before his Spanish sojourn. ↩︎