Found in the house of a farmer, near Florence, before 1843; Paolo Fumagalli, Florence; James Jackson Jarves (1818–1888), Florence, by 1859

The panel support, of a vertical grain, is 3.3 centimeters thick and comprises three members: a central plank 35.7 centimeters wide and two lateral planks each approximately 20 centimeters wide. A channel to receive a cross-grain batten, 21.5 centimeters wide, has been slightly recessed in the back of the panel below the tympanum; two massive nails securing this batten are embedded in the panel, their heads hidden beneath the spandrel decoration on the front. A similar recess to house a batten across the bottom of the panel is only 12.5 centimeters wide and displays no evidence of nails anywhere along its length, suggesting that a minimum of 9 centimeters have been lost at this edge. The side edges of the panel are intact, retaining gesso drips from their preparation. The painted tympanum is fashioned of a vertical panel 3.5 centimeters thick, affixed to the top of the support panel. This, too, seems to be made of three planks, the center one measuring 23.5 centimeters wide. A split along the center of this plank is the only defect in the carpentry visible through the paint and gilded surfaces. Two notches cut into the top edge of this panel, approximately 5 centimeters wide, 2 centimeters long, and 29 centimeters apart, indicate the placement of a pinnacle panel above the tympanum frame, now lost. The tympanum is bordered by an engaged molding 3.5 centimeters thick that formerly extended around the entire perimeter of the panel. The sections of this molding that had been engaged below the tympanum were secured there after the altarpiece had been dismembered, probably in the eighteenth or early nineteenth century, and were removed by Andrea Rothe during a treatment at the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, in 1999.1

Gilding throughout the main image is beautifully preserved, though it has been harshly abraded in the tympanum and nearly effaced along the raised moldings. The paint surface throughout has been heavily and evenly abraded, except where it was covered by the moldings engaged along the edges of the composition. These slivers of protected surface indicate how extensive are the losses of modeling effects and of colored glazes across the rest of the painting: the yellow draperies were glazed green over highlights and red in shadows, the white draperies were glazed blue, and the cloth of honor had red glazes reinforcing the orange and red sgraffito decoration that remains. The blue draperies of Christ and the Virgin are, in their present state, an invention of Andrea Rothe, following rudimentary indications of modeling deduced from incisions in the gesso ground.

Christ, wearing the pallium of a priest and bearing the crown and scepter of a king, is seated frontally on a cushion before an elaborate brocade hanging. The cushion is notionally resting on the seat of a throne, but the architecture of the throne is entirely obscured by the hanging, which is rendered as though suspended from ties linked to fictive rings along the framing of the arched top of the scene. Christ supports on His right thigh a book, opened to the ornate capitals Alpha and Omega. To His left sits the Virgin, also crowned, turned three-quarters toward her Son, her hands crossed before her breast in a gesture of humility. A mandorla of red seraphim and blue cherubim encircles the two figures, while six music-making angels kneel in the foreground, singing and playing horns and a viol. Filling the spandrels of the frame above the main picture field are allegories of the old and new dispensation. On the right, Synagoga is represented as an old woman, stooped, dressed in black, and blindfolded, with a naked child in her arms and an altar table with a sacrificial ox behind her. She is identified by the inscription HAEBEBIS DEO[S] (Exodus 20:3; Thou shalt have no other gods before me) on a banderole held by an angel flying away from her.2 On the left, Ecclesia is represented as a young woman standing proudly upright, crowned and wearing white, holding a chalice and paten for the Eucharist in her left hand and, with her right, blessing a child standing in a baptismal font. She, too, is identified by an inscribed banderole, reading ECCE NOVA FACIO (Revelations 21:5; Behold I make all things new).

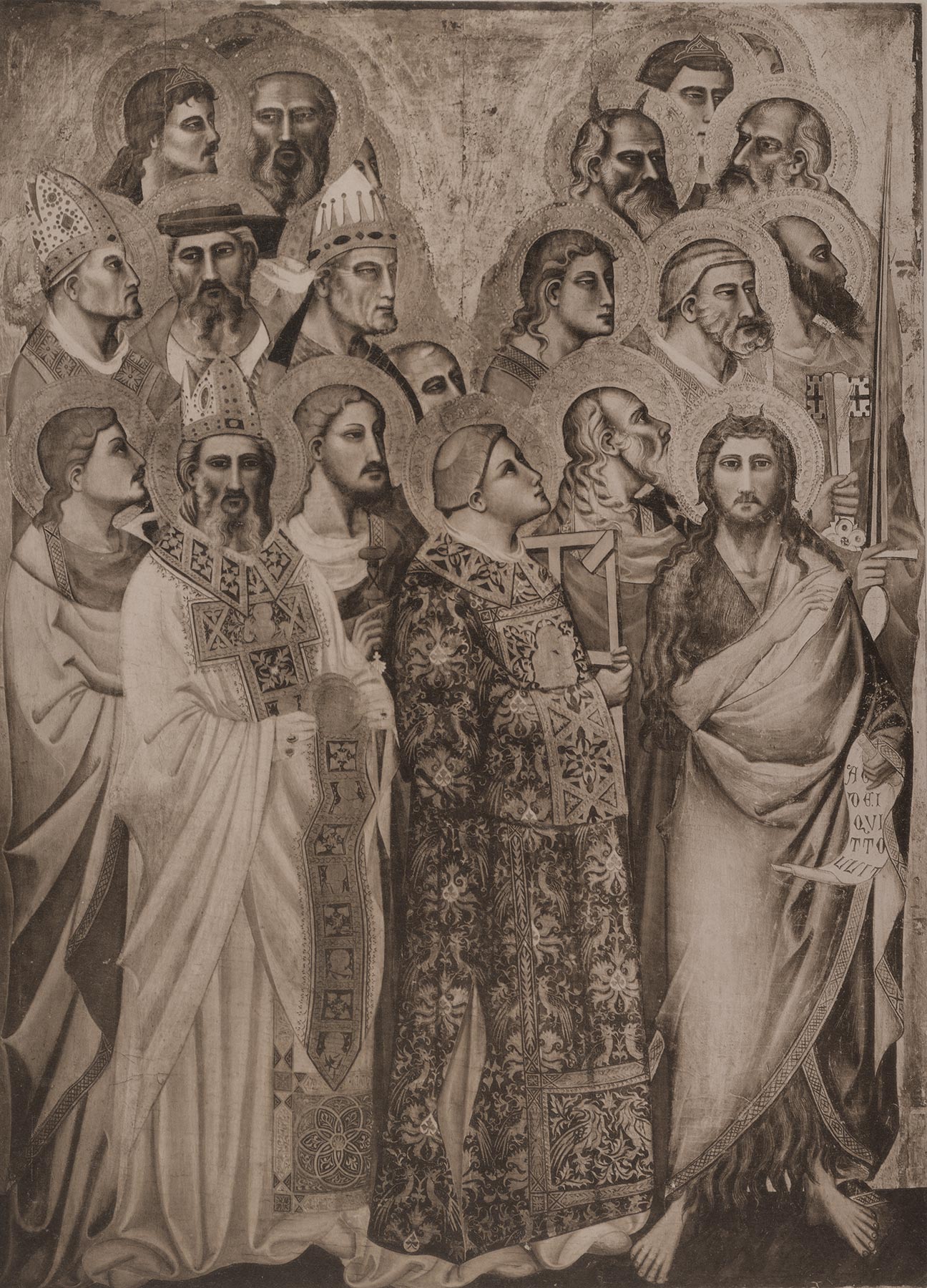

The Yale Christ and the Virgin Enthroned has been central to discussions of Giovanni del Biondo as an artist nearly since he was first recognized as an independent personality by Wilhelm Suida in the early years of the twentieth century.3 It was first labeled with Giovanni del Biondo’s name in 1916, when Osvald Sirén recognized it and two panels then in the Pinacoteca Vaticana, now in the private papal apartments at the Vatican (figs. 1–2), as fragments of a single altarpiece.4 The Vatican panels represent the choirs of saints populating the Kingdom of Heaven, completing the image of Christ and the Virgin presiding over their court in the Yale panel. The association of these three panels and their attribution to Giovanni del Biondo are undoubtedly correct and have never been questioned. Dating the panels to the artist’s early career has also been a subject of consensus. Raimond van Marle proposed a date around 1373 for the altarpiece,5 with which Richard Offner was largely in agreement.6 Sirén, followed by Charles Seymour, Jr., pushed the dating slightly earlier, to about 1370,7 and Miklós Boskovits moved it earlier still, to ca. 1360–65,8 but no writer has suggested moving it to the second half of Giovanni del Biondo’s career. Erling S. Skaug presented evidence for dating the panels between about 1365 and 1375, with an absolute terminus post quem of 1363, based on the presence of punch mark decoration made by tools brought to Florence from Siena in that year and for the most part disappearing from Florentine paintings slightly more than a decade later.9

Klara Steinweg observed that, while the ranks of saints portrayed in the Vatican panels include the patriarchs, doctors, confessors, martyrs, and virgins, the mendicant orders are represented only by Franciscans: Saints Francis and Clare, with Saint Elizabeth of Hungary, patron of the Third Order of Saint Francis.10 Combined with the observation that the motif of Ecclesia and Synagoga appearing in the spandrels of the frame on the Yale panel, while fairly common in medieval iconography generally, only occurs in Florence in a single other example—the decorative painted border of Taddeo Gaddi’s fresco of the Crucifixion in the sacristy at Santa Croce—she inferred a probable original provenance from a Franciscan convent. She further suggested that the prominence accorded Saint John the Baptist in the foreground immediately to Christ’s right, and the rarity of coupling the allegory of Ecclesia with the rite of baptism, might imply that the altarpiece was commissioned for a baptistry or baptismal chapel. Given the exceptional size of the reconstructed altarpiece, including pinnacles that are lost or unidentified today and possibly a predella, also lost, it is reasonable to suppose that such a chapel must have been part of a conspicuously important church, possibly even Santa Croce itself.

It is scarcely to be doubted that the Yale/Vatican altarpiece was originally a Franciscan commission, but it is possible that identifying further missing fragments from it might suggest an intended location other than a baptismal chapel. Photographs of the Vatican panels outside of their modern frames reveal that their overall shape probably mirrored that of the Yale panel, with a single trapezoidal pinnacle surmounting the two arched compartments framing the painted choirs of saints (see figs. 1–2).11 This left an unusually large spandrel area between the two arches, just under 50 centimeters wide at its maximum extension, that must have been filled with painted imagery. Such areas in later altarpieces of approximately this form (i.e., five painted compartments but only three pinnacles, the two compartments on either side of the central compartment being conjoined beneath a single pinnacle) are often filled with tondi representing prophets or an Annunciation group. No suitable paintings of prophets attributable to Giovanni del Biondo are known, but one Annunciation group that could possibly have served this function is the pair of panels formerly in the Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, New York (figs. 3–4), which are clearly of a congruent style and date to the Yale and Vatican panels.12 These are conventionally supposed to have been fragments cut out of a single narrative panel, which may be correct but which cannot be demonstrated any more conclusively than can a possible provenance from the spandrels or pinnacles of a large altarpiece.

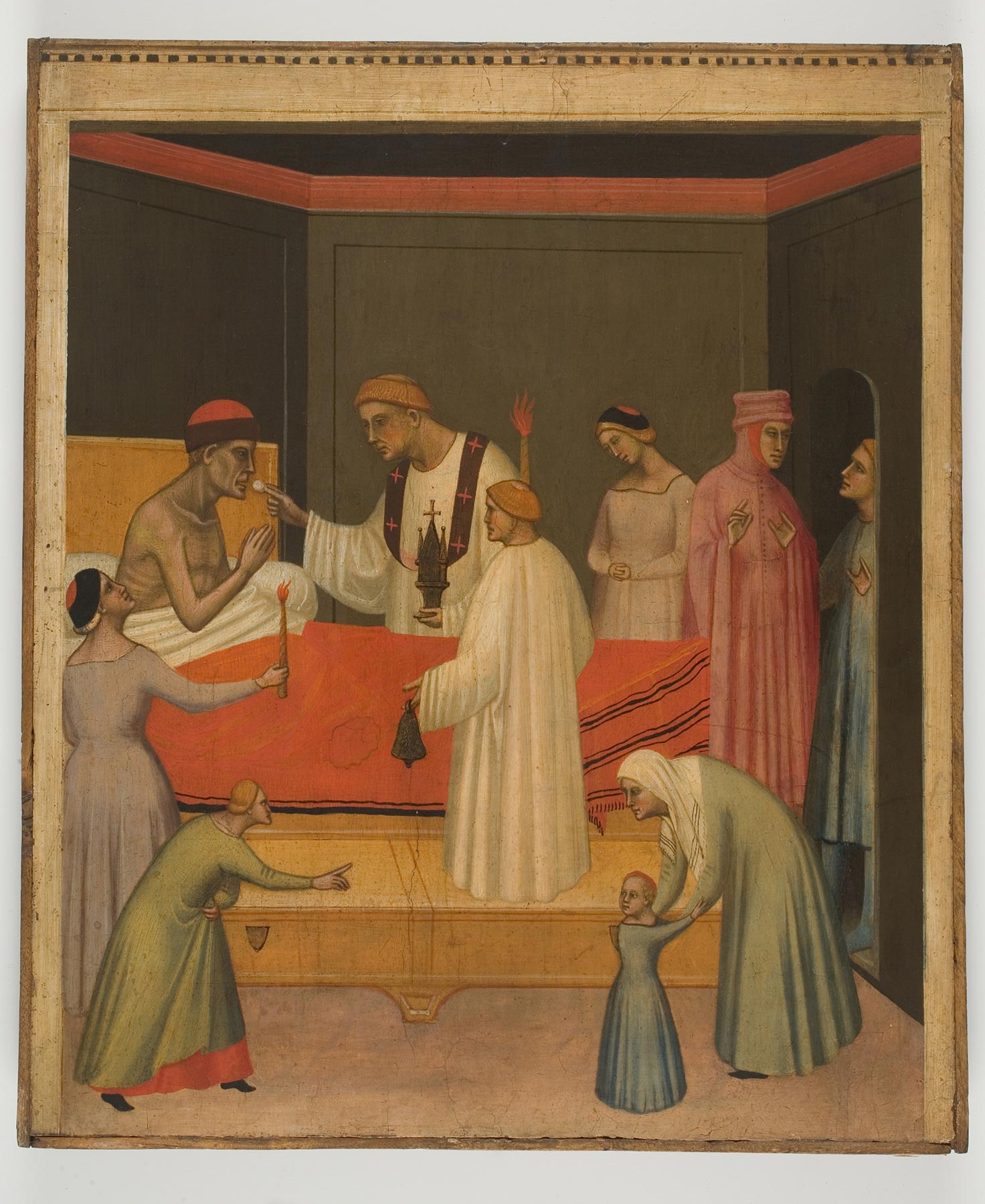

Two panels now in the Worcester Art Museum, Massachusetts (figs. 5–6), present an even more intriguing possibility as fragments either of the missing Vatican spandrels or of the pinnacles that must have stood above them. These represent two of the seven Sacraments: Communion (represented as the last communion of an elderly man) and Extreme Unction.13 Both panels, which measure 47.8 by 40.3 centimeters, have been thinned and marouflaged onto new panel supports, but the wood grain of their original supports is apparently vertical. They are unlikely, therefore, to have been part of a conventional predella, and it is sometimes assumed that they stood, together with four or more missing scenes, in columns alongside a single vertical image. The rarity of their subjects makes it difficult to find convincing parallels for a proposed reconstruction, but if they were removed from some part of the Yale/Vatican altarpiece, they could be interpreted as a continuation of the iconography of Baptism, another Sacrament, introduced in the spandrels of the frame of the Yale panel. Narrative scenes of a closely comparable format appear in the pinnacles of Giovanni del Biondo’s later Cavalcanti altarpiece in the Galleria dell’Accademia, Florence,14 the general structure of which mimics that of the Yale/Vatican altarpiece, with the addition of freestanding pediments painted with seraphim and cherubim covering the spandrel areas of the main panel frames. If such a reconstruction is possible, additional Sacraments could be supposed to have been portrayed in the missing predella from the altarpiece, or in some other part of the altarpiece frame, and they would not, then, have been the same size or format as the two panels in Worcester.

Only the eventual recovery of additional Sacrament scenes could demonstrate the validity of this hypothesis, but if it should prove to be correct, it would imply that the altarpiece did not necessarily stand in a baptismal chapel but might rather have stood in a chapel with a dedication to all seven Sacraments. Saint John the Baptist might then be assumed to have been accorded a position of prominence to indicate his role as patron of the city of Florence, rather than as originator of the rite of baptism. While it is common to find designated Sacrament chapels in Venetian churches, liturgical practice in Florence does not seem to have provided for chapels nominally reserved for a sacramentary function. It is perhaps worth speculating on the possibility that the Yale/Vatican altarpiece may have been intended for the main chapel in the sacristy of the church of Santa Croce, but no documentation of the original ornament of that altar is known to survive. In 1379 Giovanni del Biondo painted the altarpiece for the choir chapel (Rinuccini Chapel) of the sacristy, still in situ today.15 —LK

Published References

La Farina, Giuseppe. “Osservazioni sulla pittura italiana anteriore a Cimabue a proposito di un quadro nuovamente scoperto.” Giornale Euganeo di scienze, lettere ed arti 2, no. 1 (1843): 11–27., 19–22; Museo di pittura e scultura, ossia raccolta dei principali quadri, statue e bassirilievi della gallerie pubbliche e private d’Europa. Vol. 13. Florence: Paolo Fumagalli, 1845., 156; Jarves, James Jackson. Descriptive Catalogue of “Old Masters” Collected by James J. Jarves to Illustrate the History of Painting from A.D. 1200 to the Best Periods of Italian Art. Cambridge, Mass.: H. O. Houghton, 1860., 42, no. 8; Sturgis, Russell, Jr. Manual of the Jarves Collection of Early Italian Pictures. New Haven: Yale College, 1868., 20–21, no. 5; W. F. Brown, Boston. Catalogue of the Jarves Collection of Early Italian Pictures. Sale cat. November 9, 1871., 11–12, no. 5; Rankin, William. “Some Early Italian Pictures in the Jarves Collection of the Yale School of Fine Arts at New Haven.” American Journal of Archaeology 10, no. 2 (April–June 1895): 137–51., 138; Rankin, William. Notes on the Collections of Old Masters at Yale University, the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, the Fogg Museum of Harvard University. Wellesley, Mass.: Department of Art, Wellesley College, 1905., 7, no. 5; Sirén, Osvald. A Descriptive Catalogue of the Pictures in the Jarves Collection Belonging to Yale University. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1916., 47–49, no. 19; Sirén, Osvald. “Italian Pictures of the Fourteenth Century in the Jarves Collection.” Art in America 4, no. 4 (June 1916): 207–23., 215–17, fig. 7; Kurzwelly, J. “Giovanni del Biondo.” In Allgemeines Lexikon der bildenden Künstler, ed. Ulrich Thieme and Felix Becker. Leipzig, Germany: E. A. Seemann, 1921., 111; Sirén, Osvald. “Alcune note aggiuntive a quadri primitivi nella galleria vaticana.” L’arte 24 (1921): 97–102., 97; van Marle, Raimond. The Development of the Italian Schools of Painting. Vol. 3. The Hague: M. Nijhoff, 1924., 520–21, no. 19, fig. 9; Offner, Richard. Italian Primitives at Yale University: Comments and Revisions. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1927., 18–19, fig. 9; Salmi, Mario. Review of Italian Primitives at Yale University: Comments and Revisions, by Richard Offner. Rivista d’arte 11 (1929): 267–73., 268–69; Berenson, Bernard. Pitture italiane del Rinascimento: Catalogo dei principali artisti e delle loro opera. Trans. Emilio Cecchi. Milan: Ulrico Hoepli, 1936., 208; Middeldorf, Ulrich. “Ein neuer Nardo di Cione.” Mitteilungen des Kunsthistorischen Institutes in Florenz 7, nos. 3–4 (July 1956): 169–72., 172; Offner, Richard. “A Ray of Light on Giovanni del Biondo and Niccolò di Tommaso.” Mitteilungen des Kunsthistorischen Institutes in Florenz 7, nos. 3–4 (July 1956): 173–92., 173; Offner, Richard. A Critical and Historical Corpus of Florentine Painting. Sec. 4, vol. 2, Nardo di Cione. New York: Institute of Fine Arts, New York University, 1960., 50; Berenson, Bernard. Italian Pictures of the Renaissance, A List of the Principal Artists and Their Works with an Index of Places: The Florentine School. 2 vols. London: Phaidon, 1963., 1:86; Klesse, Brigitte. Seidenstoffe in der italienischen Malerei des 14. Jahrhunderts. Bern, Switzerland: Stämpfli, 1967., 365, no. 318c; Offner, Richard, and Klara Steinweg. A Critical and Historical Corpus of Florentine Painting. Sec. 4, vol. 4, Giovanni del Biondo, pt. 1. New York: Locust Valley, 1967., 10, 81–86, pl. 19; Seymour, Charles, Jr. Early Italian Paintings in the Yale University Art Gallery. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1970., 43–45, no. 26; Fredericksen, Burton B., and Federico Zeri. Census of Pre-Nineteenth-Century Italian Paintings in North American Public Collections. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1972., 88, 599; Fahy, Everett. Review of Paintings from the Samuel H. Kress Collection: Italian Schools XII–XV Century, by Fern Rusk Shapley; Paintings from the Samuel H. Kress Collection: Italian Schools XV–XVI Century, by Fern Rusk Shapley; Early Italian Paintings in the Yale University Art Gallery, by Charles Seymour, Jr.; and Italian Primitives: The Case History of a Collection and Its Conservation, by Charles Seymour, Jr. Art Bulletin 56, no. 2 (June 1974): 283–85., 284; Boskovits, Miklós. Pittura fiorentina alla vigilia del Rinascimento, 1370–1400. Florence: Edam, 1975., 312; Mancinelli, Fabrizio. “Early Italian Paintings in the Vatican Pinacoteca.” Apollo (May 1983): 347–57., 357; Volbach, Wolfgang Fritz. Catalogo della Pinacoteca Vaticana. Vol. 2, Il trecento: Firenze e Siena. Vatican City: Libreria Editrice Vaticana, 1987., 16; Skaug, Erling S. Punch Marks from Giotto to Fra Angelico: Attribution, Chronology, and Workshop Relationships in Tuscan Panel Painting, with Particular Consideration to Florence, c. 1330–1430. 2 vols. Oslo: International Institute for Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works—Nordic Group, 1994., 1:201; Frinta, Mojmír S. Punched Decoration on Late Medieval Panel and Miniature Painting. Vol. 1, Catalogue Raisonné of All Punch Shapes. Prague: Maxdorf, 1998., 463, 514; Rothe, Andrea. “Approaches to Retouching and Restoration: Moral and Aesthetic Issues.” In Early Italian Paintings: Approaches to Conservation, ed. Patricia Sherwin Garland, 177–82. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 2003., 156–57, 178, pls. 26–29; Strehlke, Carl Brandon. “Changing Perceptions About the Conservation of Early Italian Paintings and Its Usefulness to Art Historical Research.” In Early Italian Paintings: Approaches to Conservation, ed. Patricia Sherwin Garland, 132–44. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 2003., 141–43, fig. 9.5

Notes

-

See Rothe, Andrea. “Approaches to Retouching and Restoration: Moral and Aesthetic Issues.” In Early Italian Paintings: Approaches to Conservation, ed. Patricia Sherwin Garland, 177–82. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 2003., 156–57, 178, pls. 26–29. ↩︎

-

This inscription was read by Ulrich Middeldorf and Enzo Settesoldi (recorded in Offner, Richard, and Klara Steinweg. A Critical and Historical Corpus of Florentine Painting. Sec. 4, vol. 4, Giovanni del Biondo, pt. 1. New York: Locust Valley, 1967., 84n4) as SA[CRIFICA]BERIS DEO, with no correspondence to a biblical text. ↩︎

-

Wilhelm Suida isolated eight paintings and christened their author the Master of the Rinuccini Altarpiece; see Suida, Wilhelm. Florentinische Maler um die Mitte des 14. Jahrhunderts. Zur Kunstgeschichte des Auslandes 32. Strasbourg, France: J. H. E. Heitz, 1905., 45–50. The following year, Osvald Sirén recognized this artist as Giovanni del Biondo; see Sirén, Osvald. “Notizie critiche sui quadri sconosciuti nel Museo Cristiano Vaticano.” L’arte 9 (1906): 321–35., 322, 328. ↩︎

-

Sirén, Osvald. A Descriptive Catalogue of the Pictures in the Jarves Collection Belonging to Yale University. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1916., 48–49; and Sirén, Osvald. “Italian Pictures of the Fourteenth Century in the Jarves Collection.” Art in America 4, no. 4 (June 1916): 207–23., 216–17, fig. 7. ↩︎

-

van Marle, Raimond. The Development of the Italian Schools of Painting. Vol. 3. The Hague: M. Nijhoff, 1924., 520–21, no. 19, fig. 9. ↩︎

-

Offner, Richard. Italian Primitives at Yale University: Comments and Revisions. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1927., 18–19; Offner, Richard. “A Ray of Light on Giovanni del Biondo and Niccolò di Tommaso.” Mitteilungen des Kunsthistorischen Institutes in Florenz 7, nos. 3–4 (July 1956): 173–92., 173; and Offner, Richard, and Klara Steinweg. A Critical and Historical Corpus of Florentine Painting. Sec. 4, vol. 4, Giovanni del Biondo, pt. 1. New York: Locust Valley, 1967., 10, 81–86, pl. 19. ↩︎

-

Sirén, Osvald. A Descriptive Catalogue of the Pictures in the Jarves Collection Belonging to Yale University. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1916., 49; Sirén, Osvald. “Alcune note aggiuntive a quadri primitivi nella galleria vaticana.” L’arte 24 (1921): 97–102., 97; and Seymour, Charles, Jr. Early Italian Paintings in the Yale University Art Gallery. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1970., 43–45, no. 26. ↩︎

-

Boskovits, Miklós. Pittura fiorentina alla vigilia del Rinascimento, 1370–1400. Florence: Edam, 1975., 312. ↩︎

-

Skaug, Erling S. Punch Marks from Giotto to Fra Angelico: Attribution, Chronology, and Workshop Relationships in Tuscan Panel Painting, with Particular Consideration to Florence, c. 1330–1430. 2 vols. Oslo: International Institute for Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works—Nordic Group, 1994., 1:201. ↩︎

-

Offner, Richard, and Klara Steinweg. A Critical and Historical Corpus of Florentine Painting. Sec. 4, vol. 4, Giovanni del Biondo, pt. 1. New York: Locust Valley, 1967., 81–82. ↩︎

-

For the photographs of the panels outside of their modern frames, see D’Achiardi, Pietro. I quadri primitivi della Pinacoteca Vaticana provenienti dalla Biblioteca Vaticana e dal Museo Cristiano. Rome: Danesi, 1929., 5, nos. 104–5, pls. 21–22. ↩︎

-

Offner, Richard, and Klara Steinweg. A Critical and Historical Corpus of Florentine Painting. Sec. 4, vol. 4, Giovanni del Biondo, pt. 1. New York: Locust Valley, 1967., 93–95, pl. 21; sale, Sotheby’s, New York, June 8, 2007, lot 216. The panels measure 58.4 by 38.1 centimeters (Angel) and 58.4 by 36.8 centimeters (Virgin). ↩︎

-

Offner, Richard, and Klara Steinweg. A Critical and Historical Corpus of Florentine Painting. Sec. 4, vol. 4, Giovanni del Biondo, pt. 1. New York: Locust Valley, 1967., 29–30, pl. 3. The Worcester panels were formerly in the Chalandon collection in Lyon, France; the Frank C. Smith collection in Worcester, Mass.; and the collection of Dr. and Mrs. Carlisle Adams in Charlotte, N.C. ↩︎

-

Inv. no. 8606. Offner, Richard, and Klara Steinweg. A Critical and Historical Corpus of Florentine Painting. Sec. 4, vol. 4, Giovanni del Biondo, pt. 2. New York: Locust Valley, 1969., 107–14, pl. 25; and Daniela Parenti, in Boskovits, Miklós, and Daniela Parenti, eds. Cataloghi della Galleria dell’Accademia di Firenze: Dipinti. Vol. 2, Il tardo trecento. Florence: Giunti, 2010., 56–63. ↩︎

-

Offner, Richard, and Klara Steinweg. A Critical and Historical Corpus of Florentine Painting. Sec. 4, vol. 4, Giovanni del Biondo, pt. 2. New York: Locust Valley, 1969., 77–83, pl. 20. ↩︎