Edwin Austin Abbey (1852–1911), London, by 1911; Estate of Edwin Austin Abbey, by 1931

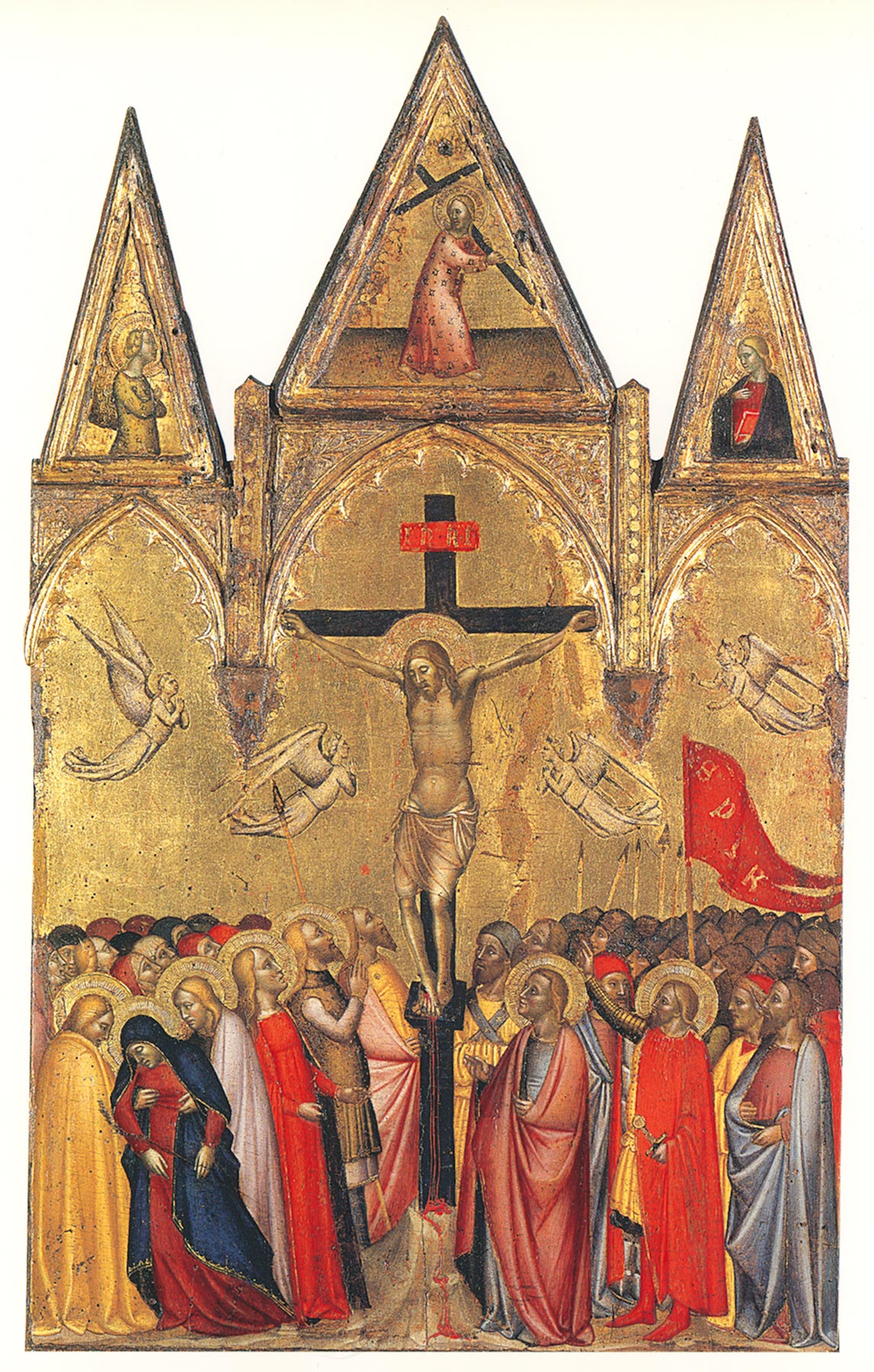

The panel, of a horizontal grain, has been thinned to a depth varying between 1.9 and 2.1 centimeters; it is uncradled and exhibits a modest convex warp. The gilding and paint surfaces have been lightly abraded but are reasonably well preserved. Continuous losses along the top and bottom edges, revealed during cleaning in 1963, were filled and painted a mottled “neutral” color in an undocumented restoration sometime before 1999. Slightly discolored local retouching from this restoration can be seen in the purple draperies of the Holy Woman at the far left, in the Magdalen’s head and neck, in Saint John the Evangelist’s jaw, and throughout the landscape setting.

This small Crucifixion was probably the central element of an unidentified predella. Standing to the immediate left of the Cross is Mary Magdalen, identified by her brilliant red robes. She appears to be gesturing toward the figure of the converted centurion Saint Longinus, kneeling in penitence at the foot of the Cross. At the extreme left is the swooning Virgin supported by Mary Cleophas and Mary Salome. Behind them is a group of female spectators. Standing on the right side of the Cross are Saint John the Evangelist and the imperial soldier who acknowledged Christ’s divinity (Matthew 27:54), gesturing toward the Cross. Behind them are various bystanders, including two Jewish priests, identified by their large conical hats. The heads of numerous helmeted soldiers are painted in the background.

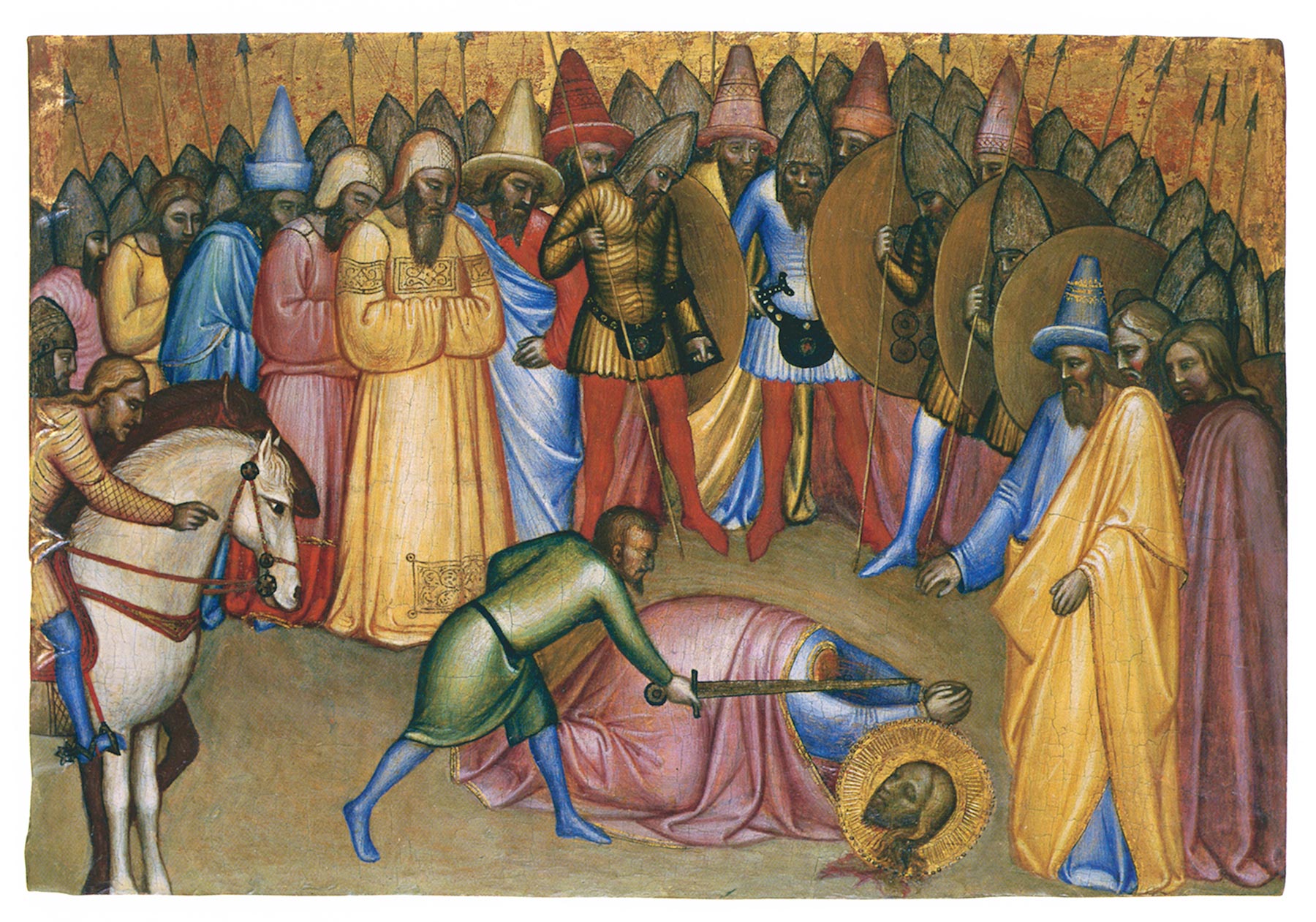

The panel, unknown to early scholarship, was first published by Charles Seymour, Jr., as a product of the Florentine school, with a date around 1385.1 In a 1986 letter to the Yale University Art Gallery, Filippo Todini first communicated his opinion that the panel was a Pisan work, by Francesco di Neri da Volterra (documented 1338–77), and associated it with a predella fragment showing the martyrdom of an unidentified saint in the Lindenau-Museum Altenburg, Germany (fig. 1).2 The attribution, later published by Todini,3 was not taken up by Carl Strehlke, who instead assigned the panel to an anonymous Florentine artist of the late 1300s in his unpublished checklist of the Italian paintings at Yale. Sonia Chiodo, on the other hand, developed Todini’s argument and discerned a stylistic relationship between the Yale and Altenburg panels and a Bishop Saint by Francesco di Neri in the Alana Collection, Newark, Delaware, and tentatively proposed that they might have been included in the same complex.4 According to Chiodo, these works, datable to around 1365–70, reflected a new stage in Francesco di Neri’s career more directly influenced by Florentine models and, in particular, the sober monumentality and incisive drawing technique of Andrea di Cione. In the most recent study of Francesco di Neri, Federica Siddi5 embraced Chiodo’s “working hypothesis” and added to the reconstruction a predella scene with the Vision of Saint Augustine, formerly in the Drey collection, Munich (current location unknown)—a work otherwise attributed to the Master of San Lucchese6 or the Master of the Misericordia.7

Todini’s 1996 attribution of the Yale panel to Francesco di Neri rested primarily on perceived links between this work and the Crucifixion on the double-sided processional banner in the Palazzo Blu, Pisa, now widely accepted as one of the artist’s last important Pisan commissions (fig. 2).8 Detailed comparisons with that image, however, reveal the intervention of a distinct personality in the present instance, markedly less oriented toward Pisan models. Notwithstanding certain iconographic parallels and similar palette choices, the short, sturdily built figures with large features and stiff gestures that characterize the Yale Crucifixion appear incompatible with the gracefully poised characters with tightly drawn, small, pinched features that populate the Pisa Crucifixion, inherently indebted to Francesco Traini’s example. The Lindenau-Museum predella, purportedly from the same complex as the Yale panel, is more nearly related and also shares some of the more exotic types among the bystanders. The uniformly finished quality, pronounced chiaroscuro, and enamel-like surface of the Lindenau picture—which have in the past invited comparison with North Italian models—provide a stark contrast, however, to the almost cursory handling of the Yale Crucifixion.9 There is a crudeness in the rendering of physiognomic details in the present work, a hastiness in the uneven application of patches of shadow, and an unfinished component that make any association between these two panels dubious at best.10

Rather than as a Pisan product influenced by Orcagnesque models, the Yale Crucifixion is perhaps better understood as a translation into vernacular terms of the lessons of Orcagna by a provincial but most likely Florentine painter or workshop. The anonymous artist’s debt to Orcagnesque models, as well as to the example of Taddeo Gaddi, whose prototypes are most clearly reflected in the proportions of the figures and in the image of Saint John the Evangelist, suggest a chronology in the 1360s or slightly later. The focus on Mary Magdalen and the unusual penitential pose of Saint Longinus might point to a confraternal commission. —PP

Published References

Seymour, Charles, Jr. Early Italian Paintings in the Yale University Art Gallery. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1970., 32, 306, no. 15; Filippo Todini, in Gold Backs, 1250–1480. Exh. cat. London: Matthiesen Fine Art, 1996., 61, fig. 1; Sonia Chiodo, in Boskovits, Miklós, ed. Italian Paintings from the 13th to the 15th Century. The Alana Collection 1. Florence: Polistampa, 2009., 70; Siddi, Federica. “Un profilo di Francesco di Neri da Volterra.” In Francesco di Neri da Volterra: La Madonna con il Bambino del Belvedere, ed. Gianluca Zanelli, 12–27. Genoa: Sagep, 2013., 18

Notes

-

Seymour, Charles, Jr. Early Italian Paintings in the Yale University Art Gallery. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1970., 32, 306, no. 15. ↩︎

-

Filippo Todoni, March 18, 1986, curatorial files, Department of European Art, Yale University Art Gallery. ↩︎

-

Filippo Todini, in Gold Backs, 1250–1480. Exh. cat. London: Matthiesen Fine Art, 1996., 61, fig. 1. ↩︎

-

Sonia Chiodo, in Boskovits, Miklós, ed. Italian Paintings from the 13th to the 15th Century. The Alana Collection 1. Florence: Polistampa, 2009., 70. ↩︎

-

Siddi, Federica. “Un profilo di Francesco di Neri da Volterra.” In Francesco di Neri da Volterra: La Madonna con il Bambino del Belvedere, ed. Gianluca Zanelli, 12–27. Genoa: Sagep, 2013., 19. ↩︎

-

Boskovits, Miklós. Pittura fiorentina alla vigilia del Rinascimento, 1370–1400. Florence: Edam, 1975., 200n87. ↩︎

-

Offner, Richard. A Critical and Historical Corpus of Florentine Painting: The Fourteenth Century. Supplement: A Legacy of Attributions. Ed. Hayden B. J. Maginnis. New York: Institute of Fine Arts, New York University, 1981., 13. ↩︎

-

See, most recently, Pisani, Linda. Cecco di Pietro e i fondi oro di Palazzo Blu. Exh. cat. Florence: Giunti, 2011., 23–29. ↩︎

-

For the attributional history of the Lindenau-Museum panel, see Stefan Weppelman, in Boskovits, Miklós, and Johannes Tripps, eds. Maestri senesi e toscani nel Lindenau-Museum di Altenburg. Exh. cat. Siena: Protagon, 2008., 224–25, no. 43. Weppelman does not identify any other pieces from the same structure. ↩︎

-

Contrary to Chiodo’s observation (in Boskovits, Miklós, ed. Italian Paintings from the 13th to the 15th Century. The Alana Collection 1. Florence: Polistampa, 2009., 72n18) that the haloes in the Altenburg and Yale painting “are absolutely identical,” the Yale panel is distinguished by the presence of another ring of small round punches on the inside of the halo. ↩︎