James Jackson Jarves (1818–1888), Florence, by 1859

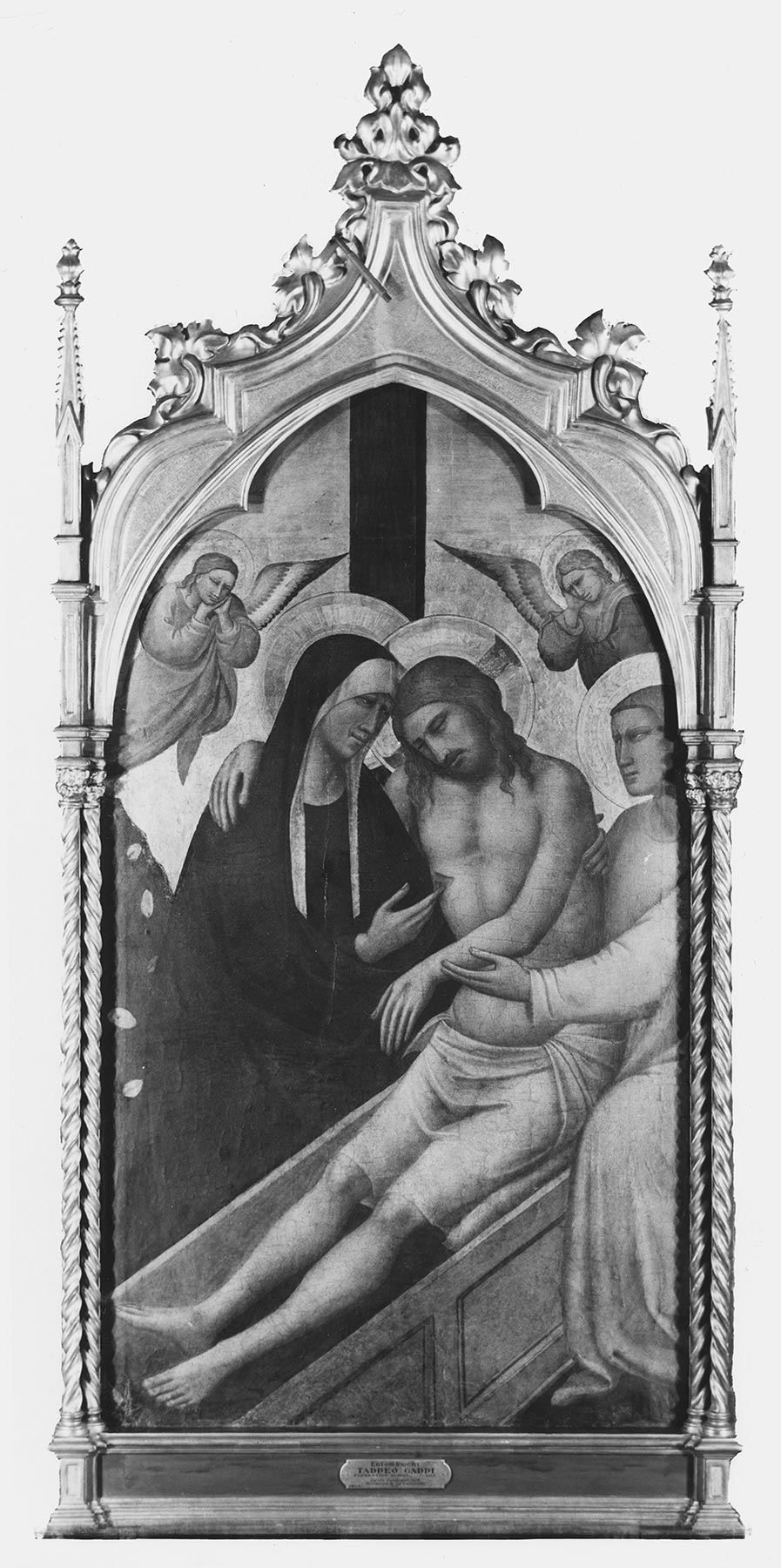

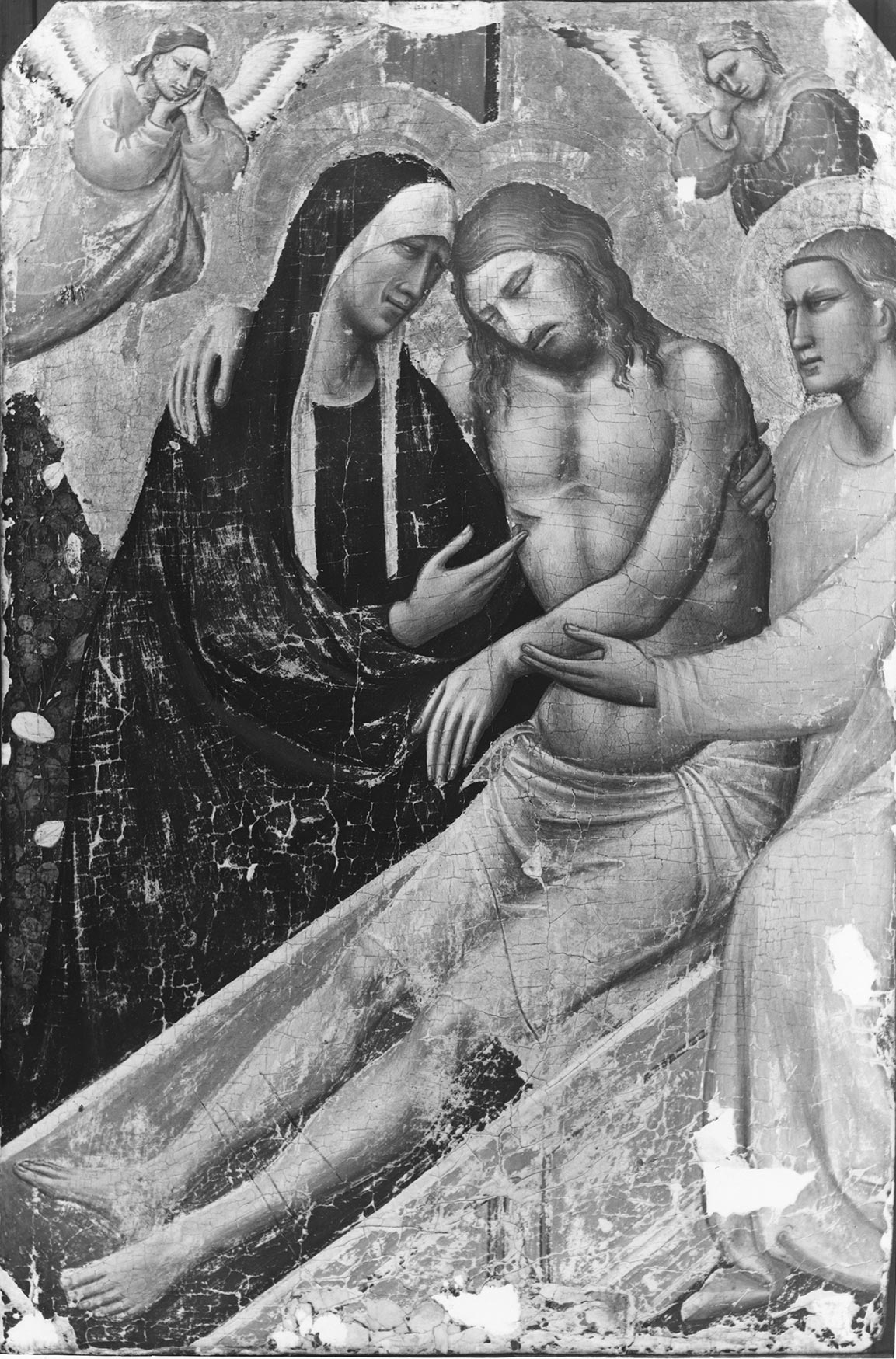

The paint and gilt surfaces appear to have been transferred to canvas, probably in the mid-nineteenth century, and mounted onto an old panel support comprised of two large poplar planks flanked by 3.5-centimeter-wide soft wood planks at the sides, 1.7 centimeters thick but not cradled.1 Heat and pressure have flattened the paint surface and impressed upon it the seams and splits (30 centimeters and 42 centimeters from the left edge) in the new support. Modern treatments by Andrew Petryn in 1951–52,2 Lance Meyers in 1986, and Elizabeth Mention in 1998 addressed faults in the panel and lifting of paint, especially around the edges, but did not take into account the transfer. Petryn removed everything he believed to be a modern addition, including a false gable supplied in the nineteenth century (fig. 1), exposing large losses in the pink robes of Saint John the Evangelist, across the bottom of the sarcophagus, and at the elbows of each mourning angel, as well as extensive abrasion through the Virgin’s cloak and the legs of Christ (fig. 2). The largest of these losses were compensated with a coarse crosshatch technique, and smaller flaking losses were covered by stippling in a color close to but not matching the surrounding surface. Some areas of white pigment, such as the ends of the Virgin’s veil and shadows in Christ’s loincloth, remain only as gesso preparation; others are intact. Flesh tones are relatively well preserved. The roses and leaves painted at the left are extremely thin. The gold ground has been entirely regilt over original gesso and bolus, but this was not disturbed by Petryn.

Sometimes referred to as a Lamentation or a Pietà, this image is actually an entirely original conflation of the two subjects with that of the Entombment of Christ. Rather than being seated on Mary’s lap or stretched out on the ground, as in traditional images of the Pietà or the Lamentation, Christ is shown inside the sarcophagus, His body supported in a seated position by the Virgin with the help of Saint John the Evangelist. Two mourning angels hover above the figures, on either side of the shaft of the Cross partially visible in the background. Behind and to the left of the Virgin is the unusual detail of a rose bush with white and red flowers. According to Saint Bernard of Clairvaux (1090/91–1153), the white rose was symbolic of Mary’s virginity, the red rose of her compassion as well as Christ’s suffering.3

Notably missing from the scene are the multiple bystanders that usually characterize scenes of the Entombment and Lamentation. The composition is instead dominated by the monumental figures of the dead Christ and the Virgin. Her mournful gaze and gesture draw the viewer’s attention to Christ’s bleeding wound, token of His Passion and sacrifice for humanity. In this respect, the painting approximates the more iconic, meditative quality of representations of the Man of Sorrows between the Virgin and Saint John the Evangelist, in which the half-length Christ is sometimes shown rising from His tomb and pointing to the open gash in His side. The transfer of this gesture to the figure of the Virgin, however, is rare in Italian panel painting and has been interpreted within the context of the theological doctrine of Mary as Coredeemer (Maria corredemptrix) that gained currency during the fourteenth century.4 The motif appears in only two other images before the fifteenth century: the left wing of a diptych by an anonymous Neapolitan follower of Giotto in the National Gallery, London (fig. 3), generally dated between around 1335 and 1345, and in Giovanni da Milano’s panel in the Galleria dell’Accademia, Florence, signed and dated 1365.5 Although indebted to a different compositional model than the Yale picture, the National Gallery painting—generally described as a Man of Sorrows—shares a similar focus on the Virgin’s gesture. The fact that the position of her right hand, with which she both touches her Son’s wound and motions toward Him, is repeated almost exactly in the present work led some scholars to speculate on a possible derivation from the same Giottesque prototype.6 Like more traditional representations of the Man of Sorrows, these powerfully contemplative images coincide with renewed devotion to the cult of Christ’s wounds during the course of the fourteenth century, when worship of the side wound, in particular, became enshrined in the liturgy and sanctioned by votive masses and papal indulgences.7

The Yale Entombment, which entered the James Jackson Jarves collection as a work of Giotto, was first attributed to Taddeo Gaddi by Osvald Sirén, who described it as “an example of Taddeo’s later academic style” and compared it to the Last Supper fresco in the refectory of the church of Santa Croce, Florence, and to the signed and dated 1355 Virgin and Child in the Gallerie degli Uffizi, Florence.8 The painting was similarly inserted among the artist’s late production by Raimond van Marle, followed by Frederick Antal, Millard Meiss, and Richard Offner.9 Charles Seymour, Jr., however, rejected a dating after 1350 in favor of an earlier chronology in the previous decade.10 Emphasizing the compositional similarities to the artist’s fresco of the Entombment in the Bardi di Vernio Chapel in Santa Croce, generally placed around 1340, as well as the correspondences with the figures in the refectory Last Supper, Seymour suggested a date between 1340 and 1350. The relationship to the Bardi di Vernio Entombment was also highlighted by Gloria Kury Keach and Massimo Ferretti, who dated the Yale panel around the middle of the 1340s.11 Andrew Ladis, on the other hand, returned to Sirén’s original assessment and reiterated, above all, the stringent correspondences between the present work and the Santa Croce refectory frescoes, which he situated around 1360, proposing an even later chronology for the Yale panel, in the final phase of the artist’s career between 1360 and 1366.12 A similar dating, around 1360 or slightly later, was advanced by Enrica Neri Lusanna and Ada Labriola.13

Undoubtedly, the most insightful analysis of the Yale Entombment remains that of Offner in his 1927 essay on Italian paintings at Yale, where he highlighted the immediate visual impact of the composition—which he referred to as a Pietà—and interpreted its “grim directness,” “uncheered and unrelieved by humor” in metaphysical terms as a conscious expression of deep religious sentiment: “The mass of the figures, their thoughtless expression, give them the air of things that are and have been in mute communion with the universe since its beginning, and are, therefore in its secret. There is a great deal of fundamental faith, of conviction in the unmindful clumsiness of the figures.”14 More often viewed in negative terms, the severe mood and at times crude execution that characterize the present image, as well as the acidic palette, find their closest equivalent, as first intuited by Sirén, in Taddeo’s frescoes for the refectory of Santa Croce. The tall, massive figures with frozen expressions are “near relatives” of the apostles in the Last Supper, whose profiles may be superimposed over that of the Yale Saint John the Evangelist (fig. 4), while the Yale Virgin is intimately related to the figure of the Magdalen below the refectory Crucifixion. Notwithstanding recent efforts to date the refectory frescoes as early as 1340,15 most authors have generally concurred in placing their execution near 1350 or later. It is difficult, in fact, to reconcile the schematic rendering and stiff formality of these images with the livelier idiom and more naturalistic approach, as well as the warmer tonalities, that generally characterize the artist’s production in the 1340s, beginning with the San Miniato al Monte frescoes, datable based on documentary evidence around 1341–42. As noted by Ladis, the grim types and stark atmosphere of these works represent a further stage in the artist’s evolution, clearly postdating the decorative concerns of the 1355 Uffizi Virgin. A date for the Yale panel around 1360 seems, therefore, highly plausible.

The original appearance and provenance of the Yale panel remain a subject of speculation. Sometime before the picture entered the Jarves collection, it had already been cut down on all sides and provided with a new summit and ogival frame that extended the vertical thrust of the composition (see fig. 1). Contrary to Keach’s assertion, however, there is no evidence to suggest that the panel was significantly reduced on both sides and that the original shape approximated that of the much larger Stigmatization of Saint Francis by Taddeo Gaddi in the Harvard University Art Museums, Cambridge, Massachusetts.16 Based on comparable devotional images, it cannot be assumed that the figures of the kneeling Evangelist or even of the two flying angels were originally complete, as claimed by Keach. A clue to the panel’s shape and structure is perhaps provided by its often-noted iconographic relationship to two later Florentine works: a panel by Giovanni del Biondo in a private collection, Florence, dated to the late 1370s,17 and a painting formerly in the Grissel collection, Oxford, most recently attributed to Tommaso del Mazza and dated between 1400 and 1405.18 Both images, which develop Taddeo’s prototype into a more traditional representation of the Lamentation by the addition of other mourners and the elimination of the tomb in favor of a cloth of honor, terminate with an ogival arch at the top, filled in by the transverse arms of the Cross, with the angels hovering below. Particularly relevant are the close correspondences, first highlighted by Antal, between the Yale Entombment and the ex-Grissel Lamentation, which has similar dimensions and proportions and includes the same iconographic motif—not present in Giovanni del Biondo’s version—of the Virgin gesturing toward Christ’s wound. The ex-Grissel panel was the central element of a triptych and was originally flanked by standing figures of Saints James the Greater and Francis, possibly indicating a comparable context for the Yale image. If this were so, the rectangular damages at the elbows of both mourning angels and the larger losses aligned across the bottom of the panel (see fig. 2) might be explained by the removal of nails securing cross battens placed at those heights.

Based on the prominence of the Cross in the background of the Yale Entombment, Seymour supposed a provenance from Santa Croce, although the inclusion of this detail is common in representations of the Man of Sorrows and Lamentation, as well as of the Pietà (see Martino di Bartolomeo, The Lamentation over the Dead Christ). At the same time, given Taddeo’s involvement in other major commissions for Santa Croce, it is not implausible that such an image, intimately related to Franciscan spirituality, could have been intended for an altar or chapel in that church.19 The fact that the composition seems to have resonated with a subsequent generation of Florentine painters suggests that the original prototype, whether invented by Taddeo or developed in Giotto’s own workshop, was most likely intended for a prominent establishment in Florence or its environs. —PP

Published References

Jarves, James Jackson. Descriptive Catalogue of “Old Masters” Collected by James J. Jarves to Illustrate the History of Painting from A.D. 1200 to the Best Periods of Italian Art. Cambridge, Mass.: H. O. Houghton, 1860., 43, no. 16; Sturgis, Russell, Jr. Manual of the Jarves Collection of Early Italian Pictures. New Haven: Yale College, 1868., 32–33; W. F. Brown, Boston. Catalogue of the Jarves Collection of Early Italian Pictures. Sale cat. November 9, 1871., 14, no. 17; Rankin, William. “Some Early Italian Pictures in the Jarves Collection of the Yale School of Fine Arts at New Haven.” American Journal of Archaeology 10, no. 2 (April–June 1895): 137–51., 140; Sirén, Osvald. “Trecento Pictures in American Collections—I.” Burlington Magazine 14, no. 68 (November 1908): 125–26., 126, pl. 2; Sirén, Osvald. A Descriptive Catalogue of the Pictures in the Jarves Collection Belonging to Yale University. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1916., 27–28, no. 8; Sirén, Osvald. Giotto and Some of His Followers. Trans. Frederic Schenck. 2 vols. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1917., 1:156, 269; Kreplin, Bernd Curt. “Taddeo Gaddi.” In Allgemeines Lexikon der bildenden Künstler: Von der Antike bis zur Gegenwart, ed. Ulrich Thieme and Felix Becker. Leipzig, Germany: E. A. Seemann, 1920., 32; van Marle, Raimond. The Development of the Italian Schools of Painting. Vol. 3. The Hague: M. Nijhoff, 1924., 342–43; Offner, Richard. Italian Primitives at Yale University: Comments and Revisions. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1927., 3, 19, fig. 10; Berenson, Bernard. Italian Pictures of the Renaissance: A List of the Principal Artists and Their Works with an Index of Places. Oxford: Clarendon, 1932., 215; Venturi, Lionello. Italian Paintings in America. Trans. Countess Vanden Heuvel and Charles Marriott. 3 vols. New York: E. Weyhe, 1933., pl. 51; Berenson, Bernard. Pitture italiane del Rinascimento: Catalogo dei principali artisti e delle loro opera. Trans. Emilio Cecchi. Milan: Ulrico Hoepli, 1936., 185; Comstock, Helen. “The Yale Collection of Italian Paintings.” Connoisseur 118 (September 1946): 45–52., 47; Antal, Frederick. Florentine Painting and Its Social Background. London: Kegan Paul, 1948., 219n66, 226n141; Meiss, Millard. Painting in Florence and Siena after the Black Death: The Arts, Religion, and Society in the Mid-Fourteenth Century. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1951., 56n165; Steegmuller, Francis. The Two Lives of James Jackson Jarves. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1951., 294; Rediscovered Italian Paintings. Exh. cat. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1952., 14–15; Berenson, Bernard. Italian Pictures of the Renaissance, A List of the Principal Artists and Their Works with an Index of Places: The Florentine School. 2 vols. London: Phaidon, 1963., 1:71; Offner, Richard, and Klara Steinweg. A Critical and Historical Corpus of Florentine Painting. Sec. 4, vol. 4, Giovanni del Biondo, pt. 2. New York: Locust Valley, 1969., 31; Seymour, Charles, Jr. Early Italian Paintings in the Yale University Art Gallery. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1970., 40–42, no. 24; Fredericksen, Burton B., and Federico Zeri. Census of Pre-Nineteenth-Century Italian Paintings in North American Public Collections. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1972., 77; Gloria Kury Keach, in Seymour, Charles, Jr., et al. Italian Primitives: The Case History of a Collection and Its Conservation. Exh. cat. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1972., 16–17, no. 7, figs. 7a–c; Ferretti, Massimo. “Una croce a Lucca, Taddeo Gaddi, un nodo di tradizione giottesca.” Paragone 27, nos. 317–19 (1976): 19–40., 25; La Favia, Louis Marcello. The Man of Sorrows and Its Origin and Development in Trecento Florentine Painting. Rome: Sanguis, 1980., 105n51; Offner, Richard. A Critical and Historical Corpus of Florentine Painting: The Fourteenth Century. Supplement: A Legacy of Attributions. Ed. Hayden B. J. Maginnis. New York: Institute of Fine Arts, New York University, 1981., 69; Ladis, Andrew. Taddeo Gaddi: Critical Reappraisal and Catalogue Raisonné. Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1982., 73, 170, 186, 190, 205, 240–41, no. 62; Neri Lusanna, Enrica. “Taddeo Gaddi.” In Enciclopedia dell’arte medievale. Rome: Istituto della Enciclopedia Italiana, 1995.; Labriola, Ada. “Gaddi, Taddeo.” In Dizionario biografico degli italiani. Rome: Istituto della Enciclopedia Italiana, 1998. https://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/.; Barbara Deimling, in Pasquinucci, Simona, and Barbara Deimling. A Critical and Historical Corpus of Florentine Painting. Sec. 4, vol. 8, Tradition and Innovation in Florentine Trecento Painting: Giovanni Bonsi–Tommaso del Mazza. Ed. Miklós Boskovits. Florence: Giunti, 2000., 131, 134, 340n2, fig. 10; Dean, Clay. A Selection of Early Italian Paintings from the Yale University Art Gallery. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 2001., 24–25, no. 5; Strehlke, Carl Brandon. “Changing Perceptions About the Conservation of Early Italian Paintings and Its Usefulness to Art Historical Research.” In Early Italian Paintings: Approaches to Conservation, ed. Patricia Sherwin Garland, 132–44. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 2003., 141–43, 155, fig. 9.6, pl. 25; Daniela Parenti, in Parenti, Daniela, ed. Giovanni da Milano: Capolavori del gotico fra Lombardia e Toscana. Exh. cat. Florence: Giunti, 2008., 232, 234; Gordon, Dillian. The Italian Paintings before 1400. National Gallery Catalogues. London: National Gallery, 2011., 377; Dominique Thiébaut, in Thiébaut, Dominique, ed. Giotto e compagni. Exh. cat. Paris: Musée du Louvre, 2013., 193n6; Aronson, Mark, Ian McClure, and Irma Passeri. “The Art of Conservation: IX, The History of Painting Conservation at the Yale University Art Gallery.” Burlington Magazine 159, no. 1367 (2017): 122–31., 122–25; Kozlowski, Sarah H. “Toward a History of the Trecento Diptych: Format, Materiality and Mobility in a Corpus of Diptychs from Angevin Naples.” Zeitschrift für Kunstgeschichte 81, no. 1 (2018): 3–29., 9, fig. 8

Notes

-

An anonymous note dated 1940 in the Yale conservation files alleging such a transfer is recorded in Aronson, Mark, Ian McClure, and Irma Passeri. “The Art of Conservation: IX, The History of Painting Conservation at the Yale University Art Gallery.” Burlington Magazine 159, no. 1367 (2017): 122–31., 124, 125n23. Although it is not reported in any other source, this appears to be true. ↩︎

-

This date is reported as 1954 in Seymour, Charles, Jr. Early Italian Paintings in the Yale University Art Gallery. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1970., 41, and as 1951–52 by Gloria Kury Keach, in Seymour, Charles, Jr., et al. Italian Primitives: The Case History of a Collection and Its Conservation. Exh. cat. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1972., 16. There is no independent documentation of the treatment in the Yale files. ↩︎

-

Joret, Charles. La rose dans l’antiquité et au moyen âge: Histoire, légendes et symbolisme. Paris: Émile Bouillon, 1892., 247. ↩︎

-

La Favia, Louis Marcello. The Man of Sorrows and Its Origin and Development in Trecento Florentine Painting. Rome: Sanguis, 1980., 107. ↩︎

-

For the most recent discussions of the National Gallery painting, part of a diptych that also included a panel with Saints John the Evangelist and Mary Magdalen in the Robert Lehman Collection, New York, see Dominique Thiébaut, in Thiébaut, Dominique, ed. Giotto e compagni. Exh. cat. Paris: Musée du Louvre, 2013., 188–93, nos. 24–25 (with previous bibliography); and Kozlowski, Sarah H. “Toward a History of the Trecento Diptych: Format, Materiality and Mobility in a Corpus of Diptychs from Angevin Naples.” Zeitschrift für Kunstgeschichte 81, no. 1 (2018): 3–29., 7–11. For the Accademia picture (inv. no. 1890 n. 8467), see Angelo Tartuferi, in Boskovits, Miklós, and Angelo Tartuferi, eds. Cataloghi della Galleria dell’Accademia di Firenze: Dipinti. Vol. 1, Dal duecento a Giovanni da Milano. Florence: Giunti, 2003., 89-93, no. 14. ↩︎

-

Gordon, Dillian. The Italian Paintings before 1400. National Gallery Catalogues. London: National Gallery, 2011., 377. ↩︎

-

Developed among mystics and the cloistered in the thirteenth century, the cult of the Five Wounds of Christ became part of the liturgy in the early fourteenth century. A votive Mass of the Five Wounds, known as Missa humiliavit and supposedly composed by Saint John the Evangelist and revealed by an angel to Pope Boniface II (r. 530–32), became especially popular and was granted indulgences first by Pope John XXII (r. 1316–34) and later Pope Innocent VI (r. 1352–62). See Gougaud, Louis. Devotional and Ascetic Practices in the Middle Ages. London: Burns, Oates, and Washbourne, 1927., 82–83; and Candelaria, Lorenzo. The Rosary Cantoral: Ritual and Social Design in a Chantbook from Early Renaissance Toledo. Rochester, N.Y.: University of Rochester Press, 2008., 66–67. There is no evidence, however, to support Louis Marcello La Favia’s claim (in La Favia, Louis Marcello. The Man of Sorrows and Its Origin and Development in Trecento Florentine Painting. Rome: Sanguis, 1980., 75), upheld in more recent literature (see Daniela Parenti, in Parenti, Daniela, ed. Giovanni da Milano: Capolavori del gotico fra Lombardia e Toscana. Exh. cat. Florence: Giunti, 2008., 232), that Pope Innocent VI instituted an official Feast of the Sacred Wounds in 1362. In fact, Carolyn Muessig has outlined the unsuccessful efforts of the Dominican friar and hagiographer Tommaso Caffarini (ca. 1350–1434) to establish “a remarkable feast day and solemn ritual for the wounds of Christ” in the early decades of the fifteenth century, by increasing the liturgical status of the Missa humiliavit from a votive to a solemn Mass; see Muessig, Carolyn. The Stigmata in Medieval and Early Modern Europe. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2020., 172–73. For an extensive discussion of devotion to the Five Wounds and its close association with devotion to the Sacred Heart, which, in turn, led to Eucharistic associations, see Gougaud, Louis. Devotional and Ascetic Practices in the Middle Ages. London: Burns, Oates, and Washbourne, 1927., 80–130. For twelfth-century mystics, the wound in the side was the direct access to the heart of Jesus, “the door in the side of the ark,” which they not only wanted to touch with the finger of their hand, like Saint Thomas, but also wished to enter completely in order to “penetrate to the very Heart of Jesus”; Gougaud, Louis. Devotional and Ascetic Practices in the Middle Ages. London: Burns, Oates, and Washbourne, 1927., 96. ↩︎

-

Inv. no. Dep. n. 3. Sirén, Osvald. “Trecento Pictures in American Collections—I.” Burlington Magazine 14, no. 68 (November 1908): 125–26., 126, pl. 2; and Sirén, Osvald. A Descriptive Catalogue of the Pictures in the Jarves Collection Belonging to Yale University. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1916., 27–28, no. 8. ↩︎

-

van Marle, Raimond. The Development of the Italian Schools of Painting. Vol. 3. The Hague: M. Nijhoff, 1924., 342–43; Antal, Frederick. Florentine Painting and Its Social Background. London: Kegan Paul, 1948., 219n66, 226n141; Meiss, Millard. Painting in Florence and Siena after the Black Death: The Arts, Religion, and Society in the Mid-Fourteenth Century. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1951., 56n165; and Offner, Richard, and Klara Steinweg. A Critical and Historical Corpus of Florentine Painting. Sec. 4, vol. 4, Giovanni del Biondo, pt. 2. New York: Locust Valley, 1969., 31. ↩︎

-

Seymour, Charles, Jr. Early Italian Paintings in the Yale University Art Gallery. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1970., 40–42, no. 24. ↩︎

-

Gloria Kury Keach, in Seymour, Charles, Jr., et al. Italian Primitives: The Case History of a Collection and Its Conservation. Exh. cat. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1972., 16–17, no. 7, figs. 7a–c; and Ferretti, Massimo. “Una croce a Lucca, Taddeo Gaddi, un nodo di tradizione giottesca.” Paragone 27, nos. 317–19 (1976): 19–40., 25. ↩︎

-

Ladis, Andrew. Taddeo Gaddi: Critical Reappraisal and Catalogue Raisonné. Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1982., 240–41, no. 62. ↩︎

-

Neri Lusanna, Enrica. “Taddeo Gaddi.” In Enciclopedia dell’arte medievale. Rome: Istituto della Enciclopedia Italiana, 1995.; and Labriola, Ada. “Gaddi, Taddeo.” In Dizionario biografico degli italiani. Rome: Istituto della Enciclopedia Italiana, 1998. https://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/.. ↩︎

-

Offner, Richard. Italian Primitives at Yale University: Comments and Revisions. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1927., 3, 19. ↩︎

-

Simbeni, Alessandro. “Gli affreschi di Taddeo Gaddi nel refettorio: Programma, committenza e datazione, con una postilla sulla diffusione del modello iconografico del Lignum vitae in Catalogna.” In Santa Croce: Oltre le apparenze, ed. Andrea De Marchi and Giacomo Piraz, 113–41. Pistoia: Gli ori, 2011., 113–41. ↩︎

-

Keach, in Seymour, Charles, Jr., et al. Italian Primitives: The Case History of a Collection and Its Conservation. Exh. cat. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1972., 16; inv. no. 1929.234, https://hvrd.art/o/304462. ↩︎

-

Offner, Richard, and Klara Steinweg. A Critical and Historical Corpus of Florentine Painting. Sec. 4, vol. 4, Giovanni del Biondo, pt. 2. New York: Locust Valley, 1969., 31–32, pl. 6. ↩︎

-

Present location unknown. See Barbara Deimling, in Pasquinucci, Simona, and Barbara Deimling. A Critical and Historical Corpus of Florentine Painting. Sec. 4, vol. 8, Tradition and Innovation in Florentine Trecento Painting: Giovanni Bonsi–Tommaso del Mazza. Ed. Miklós Boskovits. Florence: Giunti, 2000., 338–43, no. 1, pl. 63. ↩︎

-

It is worth noting that the Giottesque panel at the National Gallery, London (see fig. 3), and Giovanni da Milano’s painting in the Accademia (see note 5, above) as comparisons for the Virgin’s gesture were both executed for Franciscan institutions. A similar provenance may perhaps be adduced from the presence of Saint Francis in the triptych by Tommaso del Mazza. For Franciscan devotion to the wound in Christ’s side, see Gougaud, Louis. Devotional and Ascetic Practices in the Middle Ages. London: Burns, Oates, and Washbourne, 1927., 99–100. ↩︎