James Kerr-Lawson (1865–1939), Settignano and London, by 1906; art market, London, 1928; Maitland Fuller Griggs (1872–1943), New York, 1930

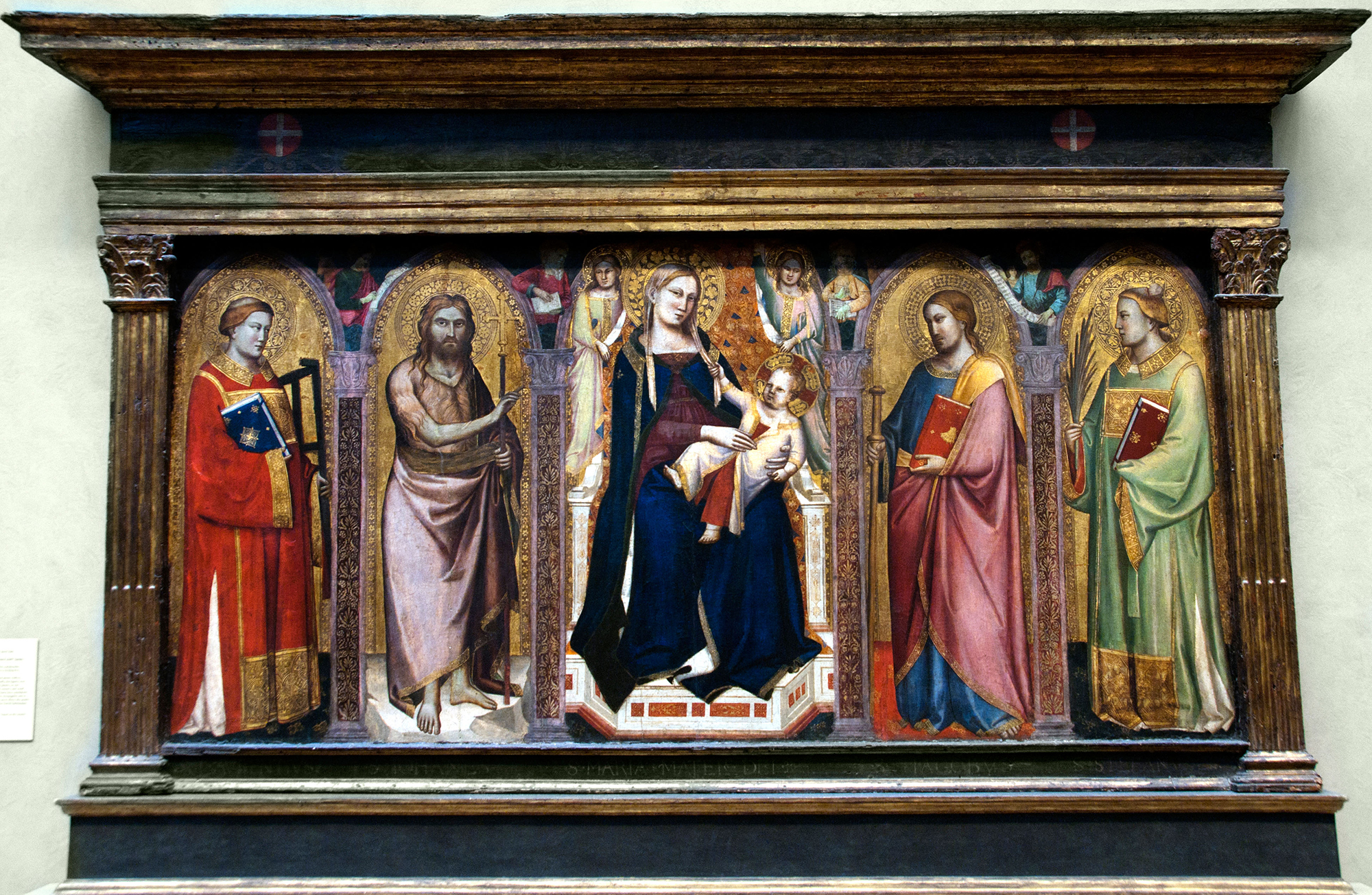

The panel support retains its original thickness of 3.6 centimeters but has been cut on all sides and reduced at the top to a trapezoidal form. Only the lower two cusps of the pastiglia arch on the left and three on the right are fully original, the others have been cut through and repaired; the top three lobes lining the arch and the upper halves of the two below them are entirely modern. Two modern battens have been applied across the back of the panel, and the wood surface there has been thickly coated with wax. Two deep, vertical splits in the panel—12 to 13 centimeters from the left edge and 7 centimeters from the right edge, as viewed from the back—run the full height of the original panel and have been impregnated with wax. Two nails from a (possibly original) batten are aligned approximately 47.5 centimeters from the bottom edge of the panel. One of these is visible on the front of the panel, at the level of the Christ Child’s breast, just beyond the tips of the fingers of the Virgin’s right hand.

The painted and gilded surfaces are generally well preserved, with the notable exception of the Virgin’s face, which is worn to its priming layer. The gilding and punching of the spandrels are modern, as is the gilding of the additions outside the trapezoidal profile of the original panel fragment. The thin projecting molding describing the framing arch is original to a point just above the capitals on either side and was silvered, now repaired. Much of the mordant gilding in the hems and cuffs is preserved, although interrupted in places. The blue of the Virgin’s robe has been overpainted, as has the olive-green front of her throne, altering its profile to make it slightly wider and covering an entire second course of moldings at its base. The corners of the ground plane painted green are false, the color covering a pinkish tone, remnants of which are also visible scattered across the white (gessoed?) area notionally in front of the throne. The gray-green “shadow” painted beneath the Virgin is also modern—painted up to the curling hem of her robe but covering her feet—as is the darker-green riser of a step painted across the full width of the panel at its lower edge. The aggregate effect of these repaints is to neutralize the ambitious three-dimensionality of the throne and, presumably, to mask damages at the bottom of the panel. It is not possible to estimate how much the panel has been cut at this edge, although judging from the exceptionally low springing height of the arch, it is possible that a considerable portion of the original composition at the bottom has been lost.

This panel, significantly altered by nineteenth-century restorations as well as by more recent cleanings, was first published by Osvald Sirén in 1906, when it was in the collection of the British-Canadian painter and dealer James Kerr-Lawson, in Settignano (Florence).1 At the time, the painting was already in fragmentary condition, cut down on all sides and inserted into a modern rectangular frame (fig. 1). Sirén’s attribution of the painting to Taddeo Gaddi was accepted by all subsequent scholars with the exception of Andrew Ladis, who included it among a large group of images he overzealously assigned to the artist’s workshop.2 Most authors have concurred in situating the Yale panel among Taddeo’s autograph production in the last phase of his career—from around the middle of the fourteenth century to his death in 1366—although disagreeing on a more precise relative chronology for the works. Sirén considered the Yale Virgin and Child Enthroned contemporary to Taddeo’s signed and dated 1355 Virgin and Child in the Gallerie degli Uffizi, Florence3—a touchstone for the artist’s late activity—while Raimond van Marle and Charles Seymour, Jr., deemed it a later effort, closer to 1360.4 An earlier chronology was first proposed by Luisa Marcucci, who dated the Yale picture between 1350 and 1355.5 Pier Paolo Donati placed it at the end of a sequence of paintings executed between 1345 and 1353—more or less coinciding with the artist’s intervention in the San Giovanni Fuorcivitas polyptych in Pistoia, completed in 1353.6 According to Donati, the Yale panel followed, in chronological order, Taddeo’s Annunciation in the Museo Bandini, Fiesole (fig. 2); his polyptych depicting the Virgin and Child Enthroned with Saints in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (fig. 3); and a triptych in the church of San Martino a Mensola, near Florence. The relationship between the Yale painting and works of the 1350s was also noted by Ladis, who followed Marcucci, however, in dating the Yale Virgin between 1350 and 1355, emphasizing above all its relationship to the San Giovanni Fuorcivitas polyptych. More recent scholarship has been divided between those who have reiterated Sirén’s opinion and proposed a chronology in proximity to or after the 1355 Virgin and Child in the Uffizi7 and others who have dated the Yale picture to around 1350.8

Notwithstanding comparisons to the San Giovanni Fuorcivitas and Uffizi Virgins, the closest analogies for the Yale panel, as first intuited by Donati, are to be found rather among those paintings situated firmly in the fifth decade of the fourteenth century. Common to these images are the ponderous figural types, along with the solid architectural details that distinguish the Yale Virgin—whose austere, simply built throne stands in marked contrast to the decorative, insubstantial structures in both the San Giovanni Fuorcivitas and Uffizi panels. Taddeo’s Annunciation in the Museo Bandini (see fig. 2), originally included in a larger altarpiece commissioned sometime between 1343 and 1350 for the church of the Compagnia di Santa Maria della Croce al Tempio in Florence, provides a firm point of reference for the Yale panel.9 The two images are defined by the same ample proportions of the figures and vivid palette of warm red, orange, and yellow tones set against blue and changeant green and include almost identical details in the rendering of the Virgin’s plain dress. Beyond these stylistic correspondences, the two pictures also share unusual technical details, such as the distinctive flower-and-leaf pattern that is tooled into the haloes of both the Yale Virgin and the Museo Bandini archangel. Perhaps not coincidentally, this motif appears in only one other work by Taddeo—in the Virgin’s halo in the Metropolitan Museum polyptych (see fig. 3), generally dated around 1340–45. The type of Christ Child in that painting is especially close to the one in the Yale picture. Among works on a comparable scale, however, the most intimately related to the present panel is the Virgin and Child formerly in the collection of Mariano Fortuny, Venice (fig. 4). Overlooked by most modern scholarship and known only through photographs, the ex-Fortuny Virgin was catalogued by Ladis as a product of Taddeo’s shop from around 1345–50.10 The same chronological parameters, in proximity to both the Museo Bandini Annunciation and the Metropolitan polyptych, but preceding the San Giovanni Fuorcivas altarpiece, apply to the Yale Virgin.

No other fragments from the same complex as the Yale panel have hitherto been identified. It is possible that a half-length figure of the Blessing Redeemer originally filled the missing pinnacle above the Virgin and Child, as in the ex-Fortuny Virgin (see fig. 4) and the slightly later triptych in San Martino a Mensola. The triptych, which shows a Virgin and Child in the center panel flanked by standing saints, may provide a clue to the original structure of the Yale altarpiece. —PP

Published References

Sirén, Osvald. Giotto: En ledning vid studiet af mästarens verk, ett törsök till framställning af det Kronologiska problemet. Stockholm: Aktiebolaget Ljus, 1906., 151; Sirén, Osvald. Giottino und seine Stellung in der gleichzeitigen florentinischen Malerei. Kunstwissenschaftliche Studien 1. Leipzig, Germany: Klinkhardt und Biermann, 1908., 88; Wehrmann, Martin. Taddeo Gaddi: Ein florentiner Maler des Trecento. Szczecin, Poland: Druck von Herrcke und Lebeling, 1910., 16; Khvoshinsky, Basile, and Mario Salmi. I pittori toscani dal XIII al XVI secolo. Vol. 2, I fiorentini del trecento. Rome: Ermanno Loescher, 1914., 17; Sirén, Osvald. Giotto and Some of His Followers. Trans. Frederic Schenck. 2 vols. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1917., 1:269; Kreplin, Bernd Curt. “Taddeo Gaddi.” In Allgemeines Lexikon der bildenden Künstler: Von der Antike bis zur Gegenwart, ed. Ulrich Thieme and Felix Becker. Leipzig, Germany: E. A. Seemann, 1920., 13:32; Offner, Richard. “Due quadri inediti di Taddeo Gaddi.” L’arte 24 (1921): 116–23., 117, fig. 2; van Marle, Raimond. The Development of the Italian Schools of Painting. Vol. 3. The Hague: M. Nijhoff, 1924., 342; Sirén, Osvald. “A Madonna by Taddeo Gaddi.” Burlington Magazine 48, no. 277 (April 1926): 185–86., 185; Berenson, Bernard. Italian Pictures of the Renaissance: A List of the Principal Artists and Their Works with an Index of Places. Oxford: Clarendon, 1932., 215; Venturi, Lionello. Italian Paintings in America. Trans. Countess Vanden Heuvel and Charles Marriott. 3 vols. New York: E. Weyhe, 1933., pl. 50; Berenson, Bernard. Pitture italiane del Rinascimento: Catalogo dei principali artisti e delle loro opera. Trans. Emilio Cecchi. Milan: Ulrico Hoepli, 1936., 185; Mostra giottesca. Exh. cat. Bergamo: Instituto Italiano d’Arti Grafiche, 1937., 53, no. 148, pl. 87; Giulia Brunetti, in Sinibaldi, Giulia, and Giulia Brunetti, eds. Pittura italiana del duecento e trecento: Catalogo della mostra giottesca di Firenze del 1937. Exh. cat. Florence: Sansoni, 1943., 448–49, no. 140, figs. 140a–b; Comstock, Helen. “The Yale Collection of Italian Paintings.” Connoisseur 118 (September 1946): 45–52., 47; Berenson, Bernard. Italian Pictures of the Renaissance, A List of the Principal Artists and Their Works with an Index of Places: The Florentine School. 2 vols. London: Phaidon, 1963., 1:71; Marcucci, Luisa. Gallerie nazionali di Firenze: I dipinti toscani del secolo XIV. Cataloghi dei musei e gallerie d’Italia. Rome: Istituto Poligrafico dello Stato, 1965., 2:523; Donati, Pier Paolo. Taddeo Gaddi. Diamanti dell’arte 12. Florence: Sadea, 1966., 28; Seymour, Charles, Jr. Early Italian Paintings in the Yale University Art Gallery. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1970., 42–43, 307, no. 25; Fredericksen, Burton B., and Federico Zeri. Census of Pre-Nineteenth-Century Italian Paintings in North American Public Collections. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1972., 77; Fremantle, Richard. Florentine Gothic Painters from Giotto to Masaccio: A Guide to Painting in and near Florence, 1300 to 1450. London: Secker and Warburg, 1975., 76, fig. 142; Offner, Richard. A Critical and Historical Corpus of Florentine Painting: The Fourteenth Century. Supplement: A Legacy of Attributions. Ed. Hayden B. J. Maginnis. New York: Institute of Fine Arts, New York University, 1981., 69; Ladis, Andrew. Taddeo Gaddi: Critical Reappraisal and Catalogue Raisonné. Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1982., 151, 222, 229, no. 56; Lamb, Robert J. James Kerr-Lawson: A Canadian Abroad. Exh. cat. Windsor, Ontario: Art Gallery of Windsor, 1983., 24; Neri Lusanna, Enrica. “Taddeo Gaddi.” In Enciclopedia dell’arte medievale. Rome: Istituto della Enciclopedia Italiana, 1995.; Labriola, Ada. “Gaddi, Taddeo.” In Dizionario biografico degli italiani. Rome: Istituto della Enciclopedia Italiana, 1998. https://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/.; Branca, Mirella. “Il polittico di Taddeo Gaddi in Santa Felicita.” In Il polittico di Taddeo Gaddi in Santa Felicita a Firenze: Restauro, studi e ricerche, ed. Mirella Branca, 3–23. Florence: Leo S. Olschki, 2008., 16

Notes

-

Sirén, Osvald. Giotto: En ledning vid studiet af mästarens verk, ett törsök till framställning af det Kronologiska problemet. Stockholm: Aktiebolaget Ljus, 1906., 151. James Kerr-Lawson and his wife, Catherine, first arrived in Settignano in 1894 and spent the next forty years dividing their time between there and London. Among their neighbors in Settignano was Bernard Berenson, who took the financially strapped Kerr-Lawson under his wing and introduced him to the art-dealers’ market. From the late 1890s to the end of his life, Kerr-Lawson spent much of his time as a private dealer and expert in Old Masters, while also working as a painter and lithographer. Most of the works he dealt in, however, can neither be identified nor located. For the most comprehensive account of his life and activity, see Lamb, Robert J. James Kerr-Lawson: A Canadian Abroad. Exh. cat. Windsor, Ontario: Art Gallery of Windsor, 1983., 9–29, esp. 19–20, 24–26. ↩︎

-

Ladis, Andrew. Taddeo Gaddi: Critical Reappraisal and Catalogue Raisonné. Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1982., 151, 222, 229, no. 56. ↩︎

-

Inv. no. Dep. n. 3. ↩︎

-

Sirén, Osvald. “A Madonna by Taddeo Gaddi.” Burlington Magazine 48, no. 277 (April 1926): 185–86., 185; van Marle, Raimond. The Development of the Italian Schools of Painting. Vol. 3. The Hague: M. Nijhoff, 1924., 159; and Seymour, Charles, Jr. Early Italian Paintings in the Yale University Art Gallery. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1970., 42–43, no. 25. ↩︎

-

Marcucci, Luisa. Gallerie nazionali di Firenze: I dipinti toscani del secolo XIV. Cataloghi dei musei e gallerie d’Italia. Rome: Istituto Poligrafico dello Stato, 1965., 2:523. ↩︎

-

Donati, Pier Paolo. Taddeo Gaddi. Diamanti dell’arte 12. Florence: Sadea, 1966., 28. ↩︎

-

Neri Lusanna, Enrica. “Taddeo Gaddi.” In Enciclopedia dell’arte medievale. Rome: Istituto della Enciclopedia Italiana, 1995.; and Labriola, Ada. “Gaddi, Taddeo.” In Dizionario biografico degli italiani. Rome: Istituto della Enciclopedia Italiana, 1998. https://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/.. ↩︎

-

Branca, Mirella. “Il polittico di Taddeo Gaddi in Santa Felicita.” In Il polittico di Taddeo Gaddi in Santa Felicita a Firenze: Restauro, studi e ricerche, ed. Mirella Branca, 3–23. Florence: Leo S. Olschki, 2008., 16, argues for a date before Taddeo’s Virgin and Child for the church of Santa Felicità, Florence (ca. 1354). ↩︎

-

The insignia of the Compagnia di Santa Maria della Croce al Tempio in Florence, founded in 1343, are found in the upper corners of the Annunciation in the Museo Bandini. It has been reasonably argued that this panel was the central element of a larger complex that also included a Saint Anthony Abbot in private collection and a Saint Julian in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, inv. no. 1997.117.1, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/438020. See, most recently, Angelo Tartuferi, in Tartuferi, Angelo, ed. L’eredità di Giotto: Arte a Firenze, 1340–1375. Exh. cat. Florence: Giunti, 2008., 120–23, no. 14 (with previous bibliography). ↩︎

-

Ladis, Andrew. Taddeo Gaddi: Critical Reappraisal and Catalogue Raisonné. Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1982., 221, no. 50. The ex-Fortuny Virgin was first published as a work of Taddeo by Bernard Berenson in the 1936 Italian edition of his lists, where it was cited as being in the Fortuny collection; see Berenson, Bernard. Pitture italiane del Rinascimento: Catalogo dei principali artisti e delle loro opera. Trans. Emilio Cecchi. Milan: Ulrico Hoepli, 1936., 185. According to a note in the Fototeca Zeri, Federico Zeri Foundation, Bologna, inv. no. 1705, it was reportedly in a private collection in Verona by 1960. ↩︎