Probably Santa Maria degli Angeli, Florence, until 1808; Wildenstein and Co., by January 1952 until at least September 19531; private collection; sale, Sotheby’s, London, December 8, 1971, lot 57; Alice Loew-Beer (née Gottlieb, 1889–1979), Epsom, London; by descent to her granddaughters; sale, Sotheby’s, London, December 7, 2005, lot 33; Richard L. Feigen (1930–2021), New York, 2005

The panel has been cut on all four sides but retains its original thickness, varying from 3 to 3.4 centimeters, and exhibits a slight convex warp. It is comprised of three horizontal planks with joins approximately 21.5 centimeters from the bottom and 15.5 centimeters from the top; the joins have opened in the front, resulting in modest paint loss along their length, at the level of the bridge of the saint’s nose and just above the top corner of his book. A 3-centimeter-wide strip of gesso and repaint covers scattered losses along the right and top edges, and smaller irregular losses are scattered along the left edge. The bottom edge is irregularly damaged, and a large part of the saint’s left hand has been repainted. Two nails driven into the panel approximately on center, originally attaching a vertical batten on the back, have resulted in paint losses approximately 16 centimeters from the bottom of the panel and 12.5 centimeters from the top, just above the saint’s left eye. The gilding and paint surface are otherwise well preserved, with only minor flaking losses scattered along the raised edges of craquelure and abrasion in the saint’s rose-colored outer robe. The painting was cleaned and restored by Irma Passeri in 2008–10.

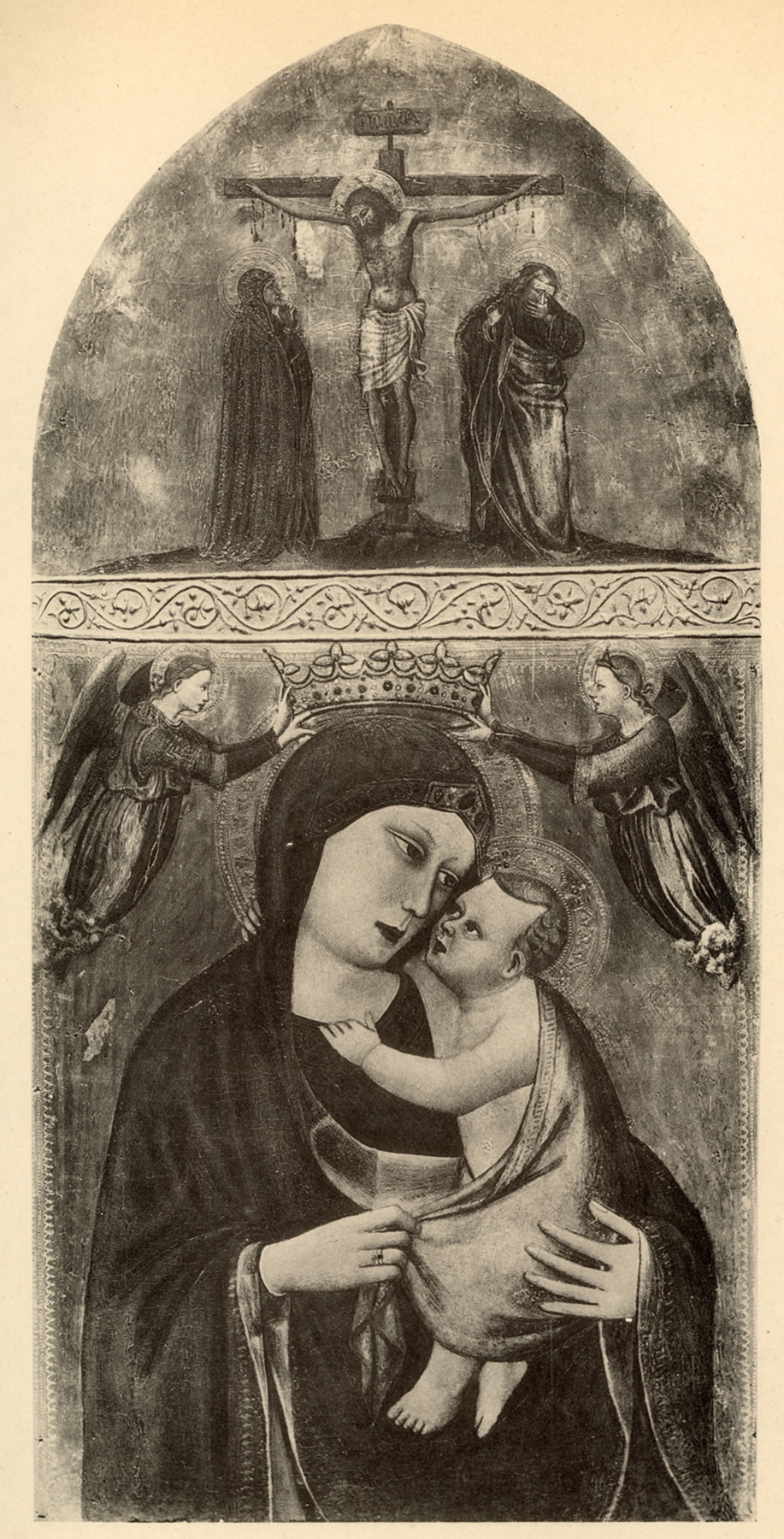

The severely damaged Virgin and Child was first published in 1936 by Bernard Berenson, who ascribed it to Bernardo Daddi, the artist it most resembled in its then–heavily repainted state (fig. 1).2 More than thirty years later, Klara Steinweg noted that “because of its deplorable condition Dr. [Richard] Offner had written the following comment on the back of the photograph[:] in large part counterfeit.”3 Steinweg herself considered the panel—following its “very careful restoration recently carried out under the instructions of Mr. Sherwood A. Fehm, Jr.”—an autograph replica by Giovanni del Biondo of a related panel formerly in the Richard M. Hurd collection, New York (fig. 2).4 Charles Seymour, Jr., in his 1970 catalogue of Italian paintings at Yale, retained Berenson’s designation “attributed to Bernardo Daddi.”5 Although he acknowledged the relationship between the Yale and Hurd paintings, Seymour rejected Steinweg’s hypothesis (if he was even aware of it, as Steinweg is not mentioned in the summary bibliography accompanying the catalogue entry) that they were both the work of Giovanni del Biondo. He maintained instead that the existence of a “later undated copy formerly in the Hurd collection, New York, testifies to the relative completeness of our panel as well as to its importance for its period.” The Yale panel is manifestly incomplete, as is indicated by the truncated haloes of two angels supporting a crown above the Virgin’s head, cropped along the arched top profile of the panel. A more accurate impression of the original appearance of the composition is provided by a second replica painted by Giovanni del Biondo, formerly in the Branch collection, Florence (fig. 3).6 Giovanni del Biondo—or another, even more Orcagnesque painter—produced yet a third replica of the composition, extended to portray the Virgin in full length and enthroned, as the center panel of an altarpiece triptych in the church of Sant’Andrea at Montespertoli in the Val d’Elsa (fig. 4),7 in this case without the angels supporting a crown above the Virgin’s head.

Miklós Boskovits, in his synthetic study of late trecento painting in Florence, repeated Steinweg’s attribution to Giovanni del Biondo for both the Hurd and Yale paintings.8 In 1984, however, he reconsidered his attribution of the Yale Virgin and Child, returning to Berenson’s original designation for it as the work of Bernardo Daddi.9 At that time, he also published two half-length saints—Saint Romuald and the present Saint John the Evangelist—as probable lateral panels of an altarpiece of which the Yale Virgin and Child formed the center. This proposal was endorsed by Erling Skaug on the basis of a conformity of punch tooling across the three panels.10 It was confirmed by the present author with the observation that splits in the horizontal grain of the wood supports in the lateral panels align with damages to the paint surface of the Virgin and Child that must have been caused by similar splits in its original support.11 In discussing the two half-length saints—which were at that time identified as Benedict and John the Evangelist—the present author argued, from the evidence of punch tooling appearing along the margin of the gold ground only on the left side of each panel, that at least two additional lateral panels and possibly five triangular gable panels might yet be missing from the reconstruction of this altarpiece. The first of these suppositions must be correct: two other lateral panels, one standing immediately to the left of the Virgin and Child, separating it from the Saint Romuald, and one at the extreme right of the complex, alongside Saint John the Evangelist, are undoubtedly missing. That any of these panels might have been surmounted by triangular gables is, however, a matter of conjecture. The punched decoration of the left margins of the lateral saints continues along the top edge of the panels, implying (although not demonstrating) the existence of a frame molding running along the top, whereas early gabled altarpieces constructed of horizontally grained panels do not generally incorporate such moldings.12

When the Saint Romuald (then called Benedict) and Saint John the Evangelist were exhibited at Yale as parts of the Richard L. Feigen collection, in 2010, the present author argued at some length that, although they are clearly parts of a single altarpiece complex, they were painted by two different artists. The two figures are slightly different from each other in scale and very different in conception and execution. Detail in the Saint Romuald, such as in the folds of his habit and hairs of his beard, is more finely rendered than in the Saint John, and the range of hue and halftones used to model Saint Romuald’s ostensibly single-colored (white) draperies is far richer than the simple, barely modulated palette of Saint John’s blue tunic and red robe. The projection in space of the book held by Saint Romuald is more aggressive than that of Saint John: the lines defining the three visible corners in the first converge toward a notional vanishing point, whereas the three corners of the second are roughly parallel to each other. The head and hands of Saint Romuald are realized with a more angular bone structure and the skin pulled tauter than in those of Saint John. These differences, furthermore, parallel very different styles of underdrawing visible on the two panels. Saint Romuald (fig. 5) employs a broad, sweeping, fluid, and forceful line applied with a brush, while Saint John (fig. 6) is composed with a thin, delicate, and tentative line probably drawn with a quill pen.

Cataloguing the punch motifs decorating the gold grounds of the three panels now at Yale, Skaug enumerated four impressions that occur regularly, and exclusively, in Bernardo Daddi’s works datable between 1334/35 and 1337/38. Impressions from a fifth punch tool that seems to have been inherited (or purchased?) from Giotto’s studio after the latter’s death in January 1337 led Skaug to accept that date as a terminus post quem for this altarpiece. Two of the punches are also found in a controversial altarpiece at San Giorgio a Ruballa near Florence, dated 1336, which the present author cited as the closest stylistic parallel for the Yale Saint Romuald among the broader category of works usually accepted as by Bernardo Daddi.13 Although sometimes discussed as a youthful work by Maso di Banco operating within Bernardo Daddi’s workshop or, alternatively, as evidence of the influence exercised by Maso on even such established masters as Bernardo Daddi, the San Giorgio a Ruballa altarpiece has been persuasively attributed to Andrea di Cione as his earliest identifiable work while apprenticed to Bernardo Daddi.14 In 2010 the present author advanced an attribution to Andrea di Cione for the Yale (then Feigen) Saint Romuald as well and tentatively proposed that Orcagna might also have been responsible for the Yale Virgin and Child, as “the emotional interaction between the [two figures] in it is more dramatic than that usually encountered in Bernardo Daddi’s many versions of this theme.”15 Assuming that the evidence of punch tooling placed these three panels squarely in Bernardo Daddi’s studio, he adduced the contrast between the Saint Romuald and the Saint John the Evangelist as evidence that the latter was the work of Bernardo Daddi, from whom the altarpiece would have been commissioned sometime around 1337. In practice, the broad, muscular conception and compromised foreshortenings of the Saint John the Evangelist bear as little relation to Bernardo Daddi’s meticulous, refined technique as does the nervous intensity and rapid, almost liquid modeling of the Saint Romuald. Beyond the evidence of its punch tooling, there is no a priori reason to assume that the Yale altarpiece was commissioned from Bernardo Daddi. Since Skaug has demonstrated that all the tools used in these panels disappear from Daddi’s production after 1338, it is at least feasible that the painting was designed and executed later in a different studio, presumably the studio of a “graduate” from Daddi’s workshop.16 There is strong reason to believe that this studio was operated by Andrea di Cione, who, it must be reaffirmed, was responsible for painting the Yale Virgin and Child and the Saint Romuald.

As difficult as it has been to establish consensus over the development or even the identity of Andrea di Cione as a painter—largely due to the collaborative nature of so much of his work—it has been even more difficult to expand the outlines of Nardo di Cione’s career beyond those first proposed by Offner in 1924.17 Paintings conventionally attributed to Nardo are all clustered either in a “documentable” (through the evidence of a change in punch tooling) late career, which covered only the years from 1363 to 1365, or a middle period nominally stretching from 1352 to 1362—that is, an arbitrary five years on either side of 1357, the date loosely associated with the frescoes in the Strozzi Chapel in Santa Maria Novella, Florence. Scholars all agree that Nardo’s career began in the 1340s since he registered in the painters’ guild sometime between 1346 and 1348 and by 1349 was recognized as one of the leading masters active in Florence.18 Few attempts to identify paintings by him that might date from this decade have been advanced; of these, Boskovits’s suggestion that the standing Virgin and Child in Minneapolis19 and the frescoes from the Giochi Bastari Chapel at the Badia Fiorentina predate midcentury deserves the most serious consideration.20 To these should be added the Whitley Madonna in Milwaukee (fig. 7), which was almost certainly painted earlier than the Minneapolis Virgin and Child, and now the Yale Saint John the Evangelist. The figure type of the Saint John, with its distinctively broad bone structure and oversize almond-shaped eye, is consistent with Nardo’s throughout his career and recurs even in such late works as the three standing saints in the National Gallery, London.21 So, too, are the inflexible joints of Saint John’s hands or the idiosyncratic “foreshortening” of his forearms, with elbows held close to the figure’s body. The close relationship between the Christ Child in the Whitley Madonna and the Yale Saint John the Evangelist should establish a standard for identifying other, hitherto unrecognized early works by Nardo.

The existence of no fewer than three replicas of the Yale Virgin and Child, two by Giovanni del Biondo, does argue for “its importance for its period,” as Seymour suggested,22 and has led to some speculation regarding the original provenance of the altarpiece of which it formed part. The white habit worn by the saint in the left lateral panel probably indicates that the altarpiece was a Camaldolese commission and led Dillian Gordon to propose changing his identification from Saint Benedict to Saint Romuald, founder of the Camaldolese reform movement.23 Following on the assumption that the altarpiece was commissioned to Bernardo Daddi in 1337, the present author noted that two chapels in the sacristy of Santa Maria degli Angeli, the principal house of the Camaldolese order in Florence, were endowed by the Spini family in 1336, one with a dedication to Saint Mary Magdalen and one with a dedication to Saint Lawrence.24 Both of these would have contained altarpieces and either could have included the Yale panels if they were originally accompanied by two additional panels, one of which would have portrayed either the Magdalen or Saint Lawrence. Gordon prefers to identify another chapel in the sacristy at Santa Maria degli Angeli as the probable original site of the Yale altarpiece. Endowed in 1342 with a bequest of 60 florins by Giovanni di Lottieri Ghitti, the dedication of this chapel to Saint John the Evangelist would be appropriate on iconographic grounds for an association with the Yale altarpiece and now seems equally compelling on stylistic grounds. Also possible but entirely speculative would be a provenance from the Camaldolese monastery of San Giovanni Evangelista at Pratovecchio; no documentation exists for the commissioning of altarpieces there in the fourteenth century. —LK

Published References

Offner, Richard. A Critical and Historical Corpus of Florentine Painting: The Fourteenth Century. Sec. 3, vol. 9, The Painters of the Miniaturist Tendency. Ed. Miklós Boskovits. Florence: Giunti, 1984., 360, pl. 186a; Offner, Richard. A Critical and Historical Corpus of Florentine Painting: The Fourteenth Century. Sec. 3, vol. 3, The Works of Bernardo Daddi. Ed. Miklós Boskovits. Florence: Giunti, 1989., 81; Skaug, Erling S. Punch Marks from Giotto to Fra Angelico: Attribution, Chronology, and Workshop Relationships in Tuscan Panel Painting, with Particular Consideration to Florence, c. 1330–1430. 2 vols. Oslo: International Institute for Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works—Nordic Group, 1994., 1:101n112, 110; Passeri, Irma. “Un trittico smembrato di Bernardo Daddi.” Kermes: La rivista del restauro 73 (January–March 2009): 5–7., 5–7; Laurence Kanter, in Kanter, Laurence, and John Marciari. Italian Paintings from the Richard L. Feigen Collection. Exh. cat. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 2010., 7–11, no. 3a; Gordon, Dillian. “The Paintings from the Early to the Late Gothic Period.” In Santa Maria degli Angeli a Firenze: Da monastero camaldolese a Biblioteca Umanistica, ed. Cristina De Benedictis, Carla Milloschi, and Guido Tigler, 188–225. Florence: Nardini, 2022., 190–91, 220n7

Notes

-

According to annotations on the reverse of two photographs in the Berenson Library, Villa I Tatti, the Harvard University Center for Italian Renaissance Studies, Settignano. ↩︎

-

Berenson, Bernard. Pitture italiane del Rinascimento: Catalogo dei principali artisti e delle loro opera. Trans. Emilio Cecchi. Milan: Ulrico Hoepli, 1936., 143. ↩︎

-

Klara Steinweg, in Offner, Richard, and Klara Steinweg. A Critical and Historical Corpus of Florentine Painting. Sec. 4, vol. 4, Giovanni del Biondo, pt. 2. New York: Locust Valley, 1969., 27. ↩︎

-

Formerly Paolo Paolini, Rome; sale, American Art Galleries, New York, December 10–11, 1924, lot 98; Richard M. Hurd, New York; sale, Kende Galleries, New York, October 29, 1945, lot 26; exhibited at the National Arts Club, New York, 1929, and at Newhouse Galleries, New York, 1937. ↩︎

-

Seymour, Charles, Jr. Early Italian Paintings in the Yale University Art Gallery. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1970., 28–29, no. 12. ↩︎

-

Formerly with Elia Volpi, Palazzo Davanzati, Florence; sale, American Art Association, New York, November 27, 1916, lot 1025, as Sano di Pietro; see Offner, Richard, and Klara Steinweg. A Critical and Historical Corpus of Florentine Painting. Sec. 4, vol. 4, Giovanni del Biondo, pt. 2. New York: Locust Valley, 1969., pl. 9. ↩︎

-

Offner, Richard, and Klara Steinweg. A Critical and Historical Corpus of Florentine Painting. Sec. 4, vol. 4, Giovanni del Biondo, pt. 2. New York: Locust Valley, 1969., pl. 44. ↩︎

-

Boskovits, Miklós. Pittura fiorentina alla vigilia del Rinascimento, 1370–1400. Florence: Edam, 1975., 312. ↩︎

-

Offner, Richard. A Critical and Historical Corpus of Florentine Painting: The Fourteenth Century. Sec. 3, vol. 9, The Painters of the Miniaturist Tendency. Ed. Miklós Boskovits. Florence: Giunti, 1984., 72, 359, 360n1, pl. 185. ↩︎

-

Skaug, Erling S. Punch Marks from Giotto to Fra Angelico: Attribution, Chronology, and Workshop Relationships in Tuscan Panel Painting, with Particular Consideration to Florence, c. 1330–1430. 2 vols. Oslo: International Institute for Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works—Nordic Group, 1994., 1:101, 110. ↩︎

-

Laurence Kanter, in Kanter, Laurence, and John Marciari. Italian Paintings from the Richard L. Feigen Collection. Exh. cat. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 2010., 10–11, fig. 1. ↩︎

-

In Offner, Richard, and Klara Steinweg. A Critical and Historical Corpus of Florentine Painting. Sec. 4, vol. 4, Giovanni del Biondo, pt. 2. New York: Locust Valley, 1969., 27, Klara Steinweg alluded to a Virgin and Child by Giovanni del Biondo in the Pinacoteca Nazionale, Siena (inv. no. 584), in which the composition is closed at the top with a small scene of the Crucifixion divided from the main figures by a course of punched decoration, as evidence that the Hurd (and Yale) paintings were probably treated in the same fashion, and she felt that this was confirmed by a similar configuration in the Virgin and Child formerly in the Branch collection (fig. 3). The latter, however, is problematic as evidence without access to the original. From the photograph published by Steinweg (Offner, Richard, and Klara Steinweg. A Critical and Historical Corpus of Florentine Painting. Sec. 4, vol. 4, Giovanni del Biondo, pt. 2. New York: Locust Valley, 1969., pl. 9), it appears that the upper and lower parts of this panel may be a marriage of fragments from two unrelated works of art: the Crucifixion appears to have been painted on a panel with a horizontal wood grain and possibly to have been enlarged to fit above the Virgin and Child, which instead was evidently painted on a panel with a vertical grain. ↩︎

-

Kanter, in Kanter, Laurence, and John Marciari. Italian Paintings from the Richard L. Feigen Collection. Exh. cat. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 2010., 10–11. ↩︎

-

Bartalini, Roberto. “Maso, la cronologia della capella Bardi di Vernio e il giovane Orcagna.” Prospettiva 77 (January 1995): 16–35., 16–35; and Parenti, Daniela. “Studi recenti su Orcagna e sulla pittura dopo la ‘peste nera.’” Arte cristiana 89, no. 806 (2001): 325–32., 325–32. ↩︎

-

Kanter, in Kanter, Laurence, and John Marciari. Italian Paintings from the Richard L. Feigen Collection. Exh. cat. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 2010., 11. ↩︎

-

This hypothesis has been vigorously denied by Erling Skaug in correspondence to the author, January–February 2020, where he insists that the panels cannot be dated later than 1338. It should be noted that another early work by Andrea di Cione, a Coronation of the Virgin with Saints in the Galleria Nazionale di Palazzo Corsini, Rome, also exclusively uses punches from Bernardo Daddi’s workshop and deploys them in a manner similar to Daddi’s own; for the Palazzo Corsini work, see Boskovits, Miklós. “Orcagna in 1357—and in Other Times.” Burlington Magazine 113, no. 818 (May 1971): 239–51., 239–51. In this case, Skaug dates the combination of punches and the pattern of their arrangement to 1343/44, which seems reasonable. ↩︎

-

Offner, Richard. “Nardo di Cione and His Triptych in the Goldman Collection.” Art in America 12, no. 3 (April 1924): 99–112., 99–112. ↩︎

-

For a full rehearsal of the documents relating to Nardo di Cione, see Offner, Richard. A Critical and Historical Corpus of Florentine Painting. Sec. 4, vol. 2, Nardo di Cione. New York: Institute of Fine Arts, New York University, 1960.. ↩︎

-

Minneapolis Institute of Art, inv. no. 68.41.7. ↩︎

-

Boskovits, Miklós. Italian Paintings of the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries. Washington, D.C.: National Gallery of Art, 2016. NGA Online Editions, https://purl.org/nga/collection/catalogue/italian-paintings-of-the-thirteenth-and-fourteenth-centuries., 314. Boskovits’s suggestion that the Virgin and Child from the workshop of Bernardo Daddi at the Yale University Art Gallery might also be an early work by Nardo di Cione is based exclusively on iconographic considerations; see inv. no. 1943.208, https://artgallery.yale.edu/collections/objects/44965. ↩︎

-

Inv. no. NG581, https://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/paintings/nardo-di-cione-three-saints. ↩︎

-

Seymour, Charles, Jr. Early Italian Paintings in the Yale University Art Gallery. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1970., 29. ↩︎

-

Gordon, Dillian. “The Paintings from the Early to the Late Gothic Period.” In Santa Maria degli Angeli a Firenze: Da monastero camaldolese a Biblioteca Umanistica, ed. Cristina De Benedictis, Carla Milloschi, and Guido Tigler, 188–225. Florence: Nardini, 2022., 190–91. ↩︎

-

Kanter, in Kanter, Laurence, and John Marciari. Italian Paintings from the Richard L. Feigen Collection. Exh. cat. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 2010., 11. ↩︎