Alfredo Barsanti (1877–1946), Rome;1 Cesare Canessa (1863–1922) and Ercole Canessa (1867–1929), New York and Paris; sale, American Art Association, New York, January 25–26, 1924, lot 153; Maitland Fuller Griggs (1872–1943), New York, 1924

The panel support, of a vertical grain, retains its original thickness of 3.1 centimeters and is composed of three planks of wood: a central plank 37.4 centimeters wide with two 4.5-centimeters-wide extensions on either side. The framing elements are all original, if unusual in their construction, and affixed to the support by heavy nails driven in back to front. The main framing surround is 2.0 centimeters wide and projects 4.3 centimeters from the surface of the support. The back panel extends 2.5 centimeters beyond the frame at either side and is gilt to its outer edges. This area outside the frame was reserved for an engaged colonette on either side, now missing, though the base of the colonette on the left side is preserved. The gilding behind the colonettes ends at the height of their capitals, level with the spring of the arch in the frame molding. The former presence of the capitals is indicated by nail holes where they were attached to the panel support. By implication, the capitals must, in turn, have supported a superstructure that is now missing: the present top edge of the panel, like its reverse, is painted red, which is old but not original. Also missing is a freestanding arcade of (probably) cusped moldings lining the inner edge of the arch at the top of the frame: a slot into which such arcades were typically glued is original. The predella, measuring 10.6 by 50.3 centimeters, is a soft wood (spruce or pine?) plank, of a horizontal grain and 2.4 centimeters thick, with a central pastiglia and gilt decorative panel measuring 5.4 by 30.2 centimeters. The molded frame surround for this decorative panel is missing, as is any painted device that might once have appeared in its central medallion. The warp of the panel support has resulted in gaps as wide as 1.5 centimeters between it and the predella at either end, but the original gesso barb where the predella once abutted the paint surface is intact.

The gilding and paint surfaces of the panel are beautifully preserved except for some abrasion to the gold on the right side of the composition and exceptionally clumsy restoration of the Christ Child’s face and right arm. The blue of the Virgin’s robe may have been executed in a distemper or glue-based medium; it retains an unusual vibrancy of color and thick, matte texture, with scattered patches of old discolored varnish. Numerous candle burns along the bottom edge of the predella cannot be associated with any damages to the paint surface but possibly indicate that the panel was hung relatively high in its original context or at some later point in its history. Eleven regularly spaced nail holes following the profile of the frame approximately 4 centimeters in from its inner face are later and cannot be explained by conventional carpentry practice. The alternating red-and-blue decoration of the dentil ornament on the frame is perfectly preserved.

This image, in its original engaged frame, was most likely an independent devotional panel rather than a fragment of a larger structure. Remarkable for its elaborately decorated surfaces, it was acquired by Maitland Griggs in 1924, as “School of Bernardo Daddi.”2 In a report to Griggs at the time of the Canessa sale, Richard Offner apparently assigned the painting to a “remote follower” of Bernardo Daddi,3 although he revised this assessment the following year, in a lecture given at the Griggs residence on January 19, 1925.4 On this occasion, Offner discussed the Virgin and Child in more appreciative terms, as the work of the same unidentified “pupil” of Bernardo Daddi who was responsible, in his view, for the signed and dated 1344 polyptych in Santa Maria Novella, as well as for the standing Saint Catherine in the cathedral of Santa Maria del Fiore and the Coronation of the Virgin in the Galleria dell’Accademia, Florence (fig. 1). Noting the “very nice state of preservation” of the Yale Virgin and Child, Offner reportedly highlighted its salient characteristics in the following terms: “There is a nice feeling of the panel and stucco and gold—a sense of the material which is unusual. Notice the flesh and veil, the tooling in the dress, the charming work in the brocade on which the Virgin stands. All this, together with the look of the eyes, the construction of the head, point to a pupil of Bernardo Daddi—and almost conclusively to the Master of the St. Catherine which is against the façade of the cathedral in Florence, the Coronation in the Academy and an altarpiece in the Cloister of S.M. Novella.”

Offner’s position, however, seems to have changed again over the course of the following decades. In the 1947 volume of the Corpus, dedicated to Daddi and his circle, the Yale panel was referred to only in passing as a “Daddesque” product and was omitted from the large body of works that the author had by then gathered around the personality of the anonymous pupil cited above, rechristened “Assistant of Daddi.”5 Offner returned to the Yale Virgin, however, in the 1958 volume of the Corpus, where he catalogued the panel more fully as “Following of Daddi” and amended his original conclusions: “If the cast and expression of the Virgin’s head and the action betray the spell of the Daddi circle,” he wrote, referring again to analogies with the 1344 Santa Maria Novella polyptych, “the small proportions of the Child and the punched ornament lead us inevitably to a period in which his immediate influence had already begun to wane. It is here replaced in part by that of Nardo and Andrea di Cione, and chiefly by that of the former.”6 Offner then went on to compare the Yale panel to Nardo di Cione’s versions of the standing Madonna in the Minneapolis Institute of Art (fig. 2) and in the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.,7 drawing stylistic as well as technical analogies with those works. While not advancing a precise chronology for the Yale picture, Offner suggested that it was later than a much-ruined image of the standing Virgin and Child by Taddeo Gaddi in the Galleria dell’Accademia, Florence, which he dated around 1345 and considered the earliest representation of the subject in Florentine painting.8

Barring an attribution to Spinello Aretino proposed by Bernard Berenson in 1932 (and later retracted),9 subsequent scholarship has essentially followed Offner’s changing views about the Yale Virgin, albeit not always reaching the same conclusions. Charles Seymour, Jr., who cited Offner’s judgment at the time of the Canessa sale, assigned the painting to a “remote follower” of Bernardo Daddi around 1350,10 while Federico Zeri listed it simply as “follower” of Bernardo Daddi.11 Erling Skaug, on the other hand, included the panel in a small group of images by different hands yet sharing many of the same punch marks, which he viewed as products of a “Post-1363 Collaboration,” a large joint enterprise comprising all the best painters in Florence, including Andrea, Nardo and Jacopo di Cione, and Giovanni da Milano.12 Carl Strehlke returned instead to an earlier chronology and preferred to label the panel as “Workshop of Bernardo Daddi, ca. 1340s.”13 A date in the 1340s was also suggested by Miklós Boskovits, although he carried Offner’s observations about the perceived Nardesque influences one step further, attributing the Yale Virgin to the earliest activity of Nardo di Cione himself. 14 For Boskovits, the present work represented further evidence of the important role played by Bernardo Daddi in the artistic formation of a younger generation of leading personalities in Florentine painting between around 1340 and 1350.

The uncertainties and disparate opinions regarding the authorship of the Yale panel reflect the full complexity of the issues that still affect the evaluation of Daddi’s personality and more specifically those works produced by the artist at the end of his career. Efforts to disengage the Yale Virgin from Daddi’s workshop or immediately following remain unconvincing. The correspondences between the present image and Nardo’s Madonnas in Minneapolis and Washington do not extend beyond a shared iconographic model. As pointed out by Skaug in reference to Offner’s observations about the similar tooling of these works, the general design of the haloes is “the most commonplace and unspecific type in the Trecento,” and the purportedly related punch marks are actually a six-petaled rosette in Nardo’s paintings and a five-petalled rosette in the present work.15 Skaug’s own arguments regarding the chronological implications of the punching in the Yale picture, however, are equally inconclusive.16 Stylistic considerations alone suggest that the Cionesque elements in the Yale picture have been overemphasized. A comparison with Nardo’s Virgin in Minneapolis, dated by Boskovits to the same moment as the Yale picture,17 reveals two altogether distinct artistic sensibilities: the one characterized by a severe, majestic formality and the other by a more gentle, playful intimacy, as well as looser execution.

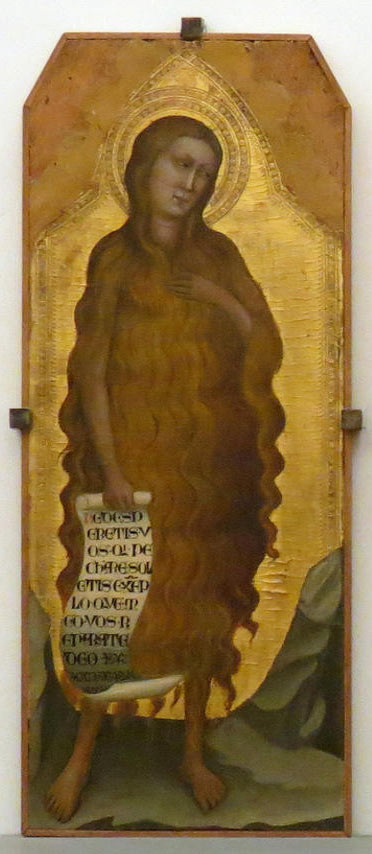

Notwithstanding some unusual components in the framing and construction of the panel, Offner’s initial response to the Yale Virgin still seems the most accurate. The relationship between this image and those paintings attributed by him to the so-called Assistant of Daddi—since recognized as products of the artist’s late workshop—is borne out by comparison with works such as the Crucifixion polyptych in the Galleria dell’Accademia, Florence. Most recently dated between 1340 and 1345, this complex is generally viewed as a collaborative effort between Daddi, whose intervention has been confined to the Crucifixion, and his shop, responsible for the execution of the standing saints in the lateral panels.18 The figure of Mary Magdalen, in particular fig. 3, shows compelling analogies to the Yale Virgin in both physiognomic type and facial expression. Additional but more generic correspondences are also discernible, as originally intuited by Offner, in the Accademia Coronation of the Virgin (see fig. 1), presently dated to the same moment as the Crucifixion altarpiece and often viewed as involving the participation of assistants.19 The slack drawing technique of the Yale panel and the at times cursory handling of individual features bring especially to mind the execution of some of the heads of the attendant saints in the Coronation. These comparisons do not necessarily imply an identity of hand, but they do suggest a possible connection between the anonymous author of the present image and the workshop of Bernardo Daddi, in the final years of the master’s activity prior to his death in 1348. —PP

Published References

American Art Galleries, New York. Illustrated Catalogue of the Art Collection of the Expert Antiquarians C. & E. Canessa of New York, Paris, Naples. Sale cat. January 25–26, 1924., lot 153; Berenson, Bernard. Italian Pictures of the Renaissance: A List of the Principal Artists and Their Works with an Index of Places. Oxford: Clarendon, 1932., 549; Frankfurter, Alfred M. “The Maitland F. Griggs Collection.” Art News 35, no. 31 (May 1, 1937): 29–46., 30; Offner, Richard. A Critical and Historical Corpus of Florentine Painting: The Fourteenth Century. Sec. 3, vol. 5, Master of San Martino alla Palma; Assistant of Daddi; Master of the Fabriano Altarpiece. New York: Institute of Fine Arts, New York University, 1947., 180; Offner, Richard. A Critical and Historical Corpus of Florentine Painting: The Fourteenth Century. Sec. 3, vol. 8, Workshop of Bernardo Daddi. New York: Institute of Fine Arts, New York University, 1958., 115–17, pl. 31; Klesse, Brigitte. Seidenstoffe in der italienischen Malerei des 14. Jahrhunderts. Bern, Switzerland: Stämpfli, 1967., 461, no. 481; Seymour, Charles, Jr. Early Italian Paintings in the Yale University Art Gallery. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1970., 28, 305, no. 11; Fredericksen, Burton B., and Federico Zeri. Census of Pre-Nineteenth-Century Italian Paintings in North American Public Collections. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1972., 600; Offner, Richard. A Critical and Historical Corpus of Florentine Painting: The Fourteenth Century. Sec. 3, vol. 3, The Works of Bernardo Daddi. Ed. Miklós Boskovits. Florence: Giunti, 1989., 84; Skaug, Erling S. Punch Marks from Giotto to Fra Angelico: Attribution, Chronology, and Workshop Relationships in Tuscan Panel Painting, with Particular Consideration to Florence, c. 1330–1430. 2 vols. Oslo: International Institute for Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works—Nordic Group, 1994., 1:191–92, 2: no. 6.13; Offner, Richard. A Critical and Historical Corpus of Florentine Painting: The Fourteenth Century. Sec. 3, vol. 5, Bernardo Daddi and His Circle. Ed. Miklós Boskovits. Florence: Giunti, 2001., 11n13, 392; Boskovits, Miklós. Italian Paintings of the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries. Washington, D.C.: National Gallery of Art, 2016. NGA Online Editions, https://purl.org/nga/collection/catalogue/italian-paintings-of-the-thirteenth-and-fourteenth-centuries., 314

Notes

-

Richard Offner states that “Mr. Maitland F. Griggs surmised the panel was at an earlier time in Sig. Barsanti’s possession in Rome”; see Offner, Richard. A Critical and Historical Corpus of Florentine Painting: The Fourteenth Century. Sec. 3, vol. 8, Workshop of Bernardo Daddi. New York: Institute of Fine Arts, New York University, 1958., 116. ↩︎

-

Illustrated Catalogue of the Ercole Canessa Collection. New York: American Art Galleries, 1924., lot 153. ↩︎

-

Seymour, Charles, Jr. Early Italian Paintings in the Yale University Art Gallery. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1970., 28. ↩︎

-

Frick Art Reference Library, New York. ↩︎

-

Offner, Richard. A Critical and Historical Corpus of Florentine Painting: The Fourteenth Century. Sec. 3, vol. 5, Master of San Martino alla Palma; Assistant of Daddi; Master of the Fabriano Altarpiece. New York: Institute of Fine Arts, New York University, 1947., 180. ↩︎

-

Offner, Richard. A Critical and Historical Corpus of Florentine Painting: The Fourteenth Century. Sec. 3, vol. 8, Workshop of Bernardo Daddi. New York: Institute of Fine Arts, New York University, 1958., 115–17, pl. 31. ↩︎

-

Inv. no. 1939.1.261, https://www.nga.gov/collection/art-object-page.204932.html. ↩︎

-

Inv. no. 1890 n. 3144. ↩︎

-

Berenson, Bernard. Italian Pictures of the Renaissance: A List of the Principal Artists and Their Works with an Index of Places. Oxford: Clarendon, 1932., 549. ↩︎

-

Seymour, Charles, Jr. Early Italian Paintings in the Yale University Art Gallery. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1970., 28. ↩︎

-

Fredericksen, Burton B., and Federico Zeri. Census of Pre-Nineteenth-Century Italian Paintings in North American Public Collections. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1972., 600. ↩︎

-

Skaug, Erling S. Punch Marks from Giotto to Fra Angelico: Attribution, Chronology, and Workshop Relationships in Tuscan Panel Painting, with Particular Consideration to Florence, c. 1330–1430. 2 vols. Oslo: International Institute for Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works—Nordic Group, 1994., 1:191–92, 2: no. 6.13. ↩︎

-

Carl Strehlke, unpublished checklist of Italian paintings at Yale, 1998–2000, curatorial files, Department of European Art, Yale University Art Gallery. ↩︎

-

Offner, Richard. A Critical and Historical Corpus of Florentine Painting: The Fourteenth Century. Sec. 3, vol. 5, Bernardo Daddi and His Circle. Ed. Miklós Boskovits. Florence: Giunti, 2001., 11n13, 392; and Boskovits, Miklós. Italian Paintings of the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries. Washington, D.C.: National Gallery of Art, 2016. NGA Online Editions, https://purl.org/nga/collection/catalogue/italian-paintings-of-the-thirteenth-and-fourteenth-centuries., 314. ↩︎

-

Skaug, Erling S. Punch Marks from Giotto to Fra Angelico: Attribution, Chronology, and Workshop Relationships in Tuscan Panel Painting, with Particular Consideration to Florence, c. 1330–1430. 2 vols. Oslo: International Institute for Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works—Nordic Group, 1994., 1:192n40. ↩︎

-

Erling Skaug grouped the Yale Virgin and Child with five unrelated paintings that have in common only their use of a set of punch tools apparently brought to Florence from Siena around 1363, probably by Giovanni da Milano; see Skaug, Erling S. Punch Marks from Giotto to Fra Angelico: Attribution, Chronology, and Workshop Relationships in Tuscan Panel Painting, with Particular Consideration to Florence, c. 1330–1430. 2 vols. Oslo: International Institute for Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works—Nordic Group, 1994., 1:192 . These punches are all documented in Sienese paintings by various artists—among them Bartolomeo Bulgarini, Niccolò di Ser Sozzo, and Luca di Tommè—who seem to have pooled resources in the wake of the plague of 1348–50. None of the punches are found in Sienese paintings predating 1348. Although Skaug dismissed the possibility of dating the Yale Virgin in the 1340s, assuming that its punch tooling cannot predate 1363, the possibility must be entertained that the single punch it employs was, in fact, brought to Siena from Florence around 1348. The likelihood of such an eventuality is suggested by the case history of punch no. 338 in Skaug’s repertory. This particular stamp was included by the author among the large set brought to Florence from Siena by Giovanni da Milano after 1363; see Skaug, Erling S. Punch Marks from Giotto to Fra Angelico: Attribution, Chronology, and Workshop Relationships in Tuscan Panel Painting, with Particular Consideration to Florence, c. 1330–1430. 2 vols. Oslo: International Institute for Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works—Nordic Group, 1994., 2: no. 6.11. However, it is also recorded in numerous Florentine paintings of the first half of the century, beginning with Giotto, and then in a single work by Pietro Lorenzetti, before reappearing in Florence later in the century; see Skaug, Erling S. Punch Marks from Giotto to Fra Angelico: Attribution, Chronology, and Workshop Relationships in Tuscan Panel Painting, with Particular Consideration to Florence, c. 1330–1430. 2 vols. Oslo: International Institute for Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works—Nordic Group, 1994., 2: no. 7.5. ↩︎

-

Boskovits, Miklós. Italian Paintings of the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries. Washington, D.C.: National Gallery of Art, 2016. NGA Online Editions, https://purl.org/nga/collection/catalogue/italian-paintings-of-the-thirteenth-and-fourteenth-centuries., 314. ↩︎

-

Angelo Tartuferi, in Boskovits, Miklós, and Angelo Tartuferi, eds. Cataloghi della Galleria dell’Accademia di Firenze: Dipinti. Vol. 1, Dal duecento a Giovanni da Milano. Florence: Giunti, 2003., 79–83, no. 12. Boskovits’s identification of Daddi’s collaborator in this work with Puccio di Simone, accepted by Tartuferi, is not persuasive. ↩︎

-

Tartuferi, in Boskovits, Miklós, and Angelo Tartuferi, eds. Cataloghi della Galleria dell’Accademia di Firenze: Dipinti. Vol. 1, Dal duecento a Giovanni da Milano. Florence: Giunti, 2003., 53–60, no. 5. ↩︎