Mrs. Benjamin Thaw (née Elma Ellsworth Dows, 1861–1931), New York; sale, Galerie Georges Petit, Paris, May 15, 1922, lot 18; Maitland Fuller Griggs (1872–1943), New York, by 1925

The paintings, originally two separate panels, were truncated across the top and trimmed at the left and right before removal from their wood supports and transfer to a single canvas support. Strips of new gold and paint were added at the left (1 centimeter), top (4 centimeters), and right (3.5 centimeters) to fill out the ogival, double-arched picture field, as was new spandrel filler. The original gold is moderately abraded, but scattered areas of loss have been cosmetically repaired with added squares of new leaf, chiefly visible around the head of the saint at the left, which was partially cleaned in 1968–69. Old retouches in that head were removed but have been left in place in the rest of the painting. These are most extensive in the lower half of the draperies of both figures. The paint film has puckered in some areas from heat applied during the transfer process, but apart from this and liberal retouching over discreet areas of small loss, the paint surface generally is well preserved, having been only modestly abraded. A prominent canvas weave is visible throughout the picture surface from the pressure of the transfer.

The two saints, identifiable as martyred deacons by their dress and palms, originally occupied the left wings of a large polyptych. Losses in the head of the saint at left that may indicate the former presence of a stone suggest that the figure could be Saint Stephen. If so, he is perhaps flanked by his traditional companion, Saint Lawrence, whose attribute, the grill of his martyrdom, may have been painted alongside the figure, near the right edge of the original panel, currently replaced by a two-inch strip of new gold. Alternatively, at least one of the two saints could be the deacon saint and martyr Saint Caesarius of Terracina, who was especially venerated in the Benedictine, and later Olivetan, monastery of San Ponziano in Lucca.1 Beyond the small areas of localized damage and notwithstanding the transfer to canvas—carried out at an unknown date before the panel’s first appearance on the art market—the image retains most of its original paint surface and elaborate punchwork. Still noteworthy are the delicate palette and lavish decoration of the saint’s vestments, characterized by broad areas of elaborate tooling and intricately designed patterns in mordant gilding.

The earliest record of the Yale Saints dates to 1922, when they appeared in the Paris sale of the collection of Mrs. Benjamin Thaw with an attribution to the Sienese school. According to records in the Yale archives, they were bought by an unnamed private dealer who listed them as works of Allegretto Nuzi, and they entered the collection of Maitland Griggs sometime before 1925.2 In a lecture at the Griggs residence on January 19, 1925, Richard Offner reportedly assigned them to “a master very close to Agnolo Gaddi’s pupil, Giovanni dal Ponte.”3 That same year, Bernard Berenson and Raimond van Marle offered their own assessments, each in correspondence with Griggs.4 In a letter dated September 10, 1925, Mary Berenson informed Griggs that “the two Deacons are, in my husband’s opinion, clearly Florentine, but again he has no name to suggest. They seem in first rate condition.” On December 12, 1925, anticipating an opinion that he would publish two years later, van Marle wrote, “As to the two saints about which you hesitate between the school of Agnolo Gaddi and Allegretto Nuzi—I think them to be by that follower of Lorenzo Monaco who passes under the name of the ‘Maestro del Bambino Vispo.’”5 While F. Mason Perkins still preferred the label “School of Agnolo Gaddi,”6 van Marle’s attribution to the Master of the Bambino Vispo—now universally recognized as Starnina—was accepted by Berenson, who included the Yale panel under the artist’s name in his list of Florentine painters.7 This identification was rejected by Charles Seymour, Jr., however, in favor of a tentative attribution to Lorenzo di Niccolò, with a date around 1410.8 Significantly, Seymour misrepresented the state of the picture, erroneously claiming that its condition was “difficult to judge” and that it was “much repainted.”

In 1971, Alvar Gonzalez-Palacios, reiterating an unpublished opinion of Federico Zeri,9 included the Yale Saints in the first reconstruction of the personality of the then-little-known Lucchese painter Giuliano di Simone, author of a signed Virgin and Child, dated 1389 in the church of San Michele at Castiglione Garfagnana (Lucca).10 According to Gonzalez-Palacios, the Saints were to be identified with the missing laterals of a Virgin and Child in the church of San Nicola in Pisa, first given to Giuliano di Simone by Zeri but otherwise assigned to Francesco Traini or his school. Barring an unpublished opinion of Everett Fahy, who proposed the name of Giovanni di Bartolomo Cristiani,11 most subsequent scholarship embraced Gonzalez-Palacios’s attribution, albeit dismissing the work’s relationship to the Pisa Madonna, which was eventually expunged from Giuliano’s oeuvre.12 In the most comprehensive discussions of Giuliano di Simone to date, Linda Pisani and Ada Labriola placed the Yale Saints among other works considered representative of the final phase of the artist’s activity, presumed not to have extended much beyond the last mention of his name in documents, in 1397.13

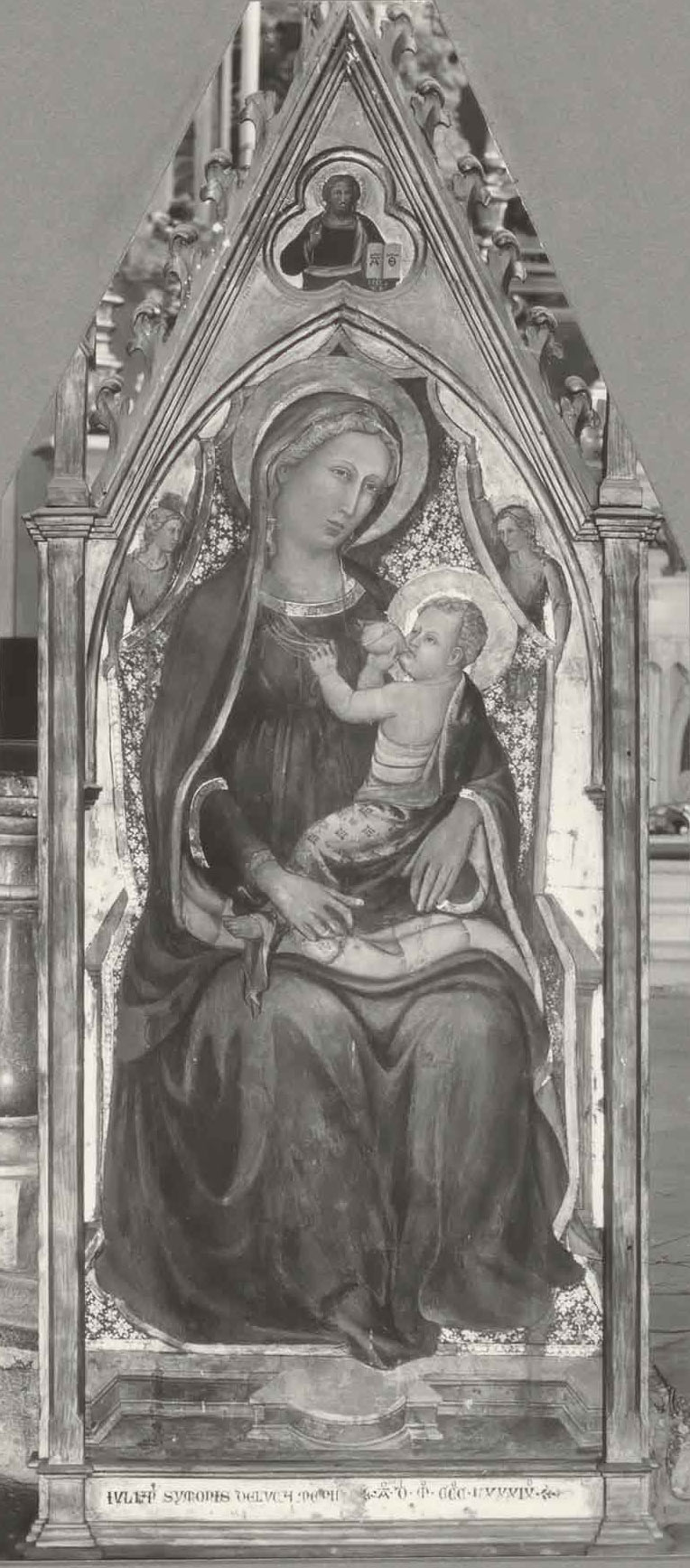

Stylistic correspondences with the Castiglione Garfagnana altarpiece—which remains Giuliano di Simone’s only signed and dated work—suggest that there is no reason to question the attribution of the Yale Saints to the artist. At the same time, the not-entirely homogeneous quality of the remaining works currently gathered under his name has resulted in a less than coherent internal chronology and inconsistent picture of his development. Although the Yale Saints take their place among Giuliano’s finest and most accomplished efforts, it is difficult to view them as a product of the same moment in the artist’s career as the polyptych in the Museo Nazionale di Villa Guinigi, Lucca, generally associated with a 1395 payment to the artist, or alongside supposedly late works, such as the Man of Sorrows in a private collection and the Crucifixion in the Kunsthaus, Zürich, as suggested by Labriola.14 The monumental proportions of the Lucca polyptych and the emotional content of the private collection and Zürich panels are inconsistent with the slender forms and detached elegance of the present figures. The attribution of the Yale Saints rests, rather, on their intimate relationship to the Castiglione Garfagnana Madonna, whose original appearance is best discerned in photographs predating its radical modern restoration (fig. 1). Although this work was already described as being in a poor state of conservation in the nineteenth century, those parts that appear still intact in old reproductions, such as the head of the Christ Child, reflect proportions and morphological characteristics identical to the Yale Saints, along with the same linear emphasis in the execution. Despite the difference in scale, further correspondences may be found in the small Virgin and Child with Saints and Reclining Eve in the Galleria Nazionale in Parma (fig. 2), first associated with the Castiglione Garfagnana Madonna by Ugo Procacci, on an indication from Offner.15 Clearly visible in the Parma picture, datable in close proximity to the Castiglione Garfagnana altarpiece but in much better condition, is the artist’s predilection for the same elaborate surface decorative effects that distinguish the Yale Saints.

Rather than harking back to the vocabulary of Spinello Aretino—whose influence on Giuliano’s formation has been overstated in recent studies—the artist’s formal and decorative vocabulary, as noted by earlier scholars, seems closely indebted to the contemporary idiom of Agnolo Gaddi. The relevance of Agnolo’s production, already implicit in Offner’s attribution of the Yale Saints to a follower, was considered self-evident by Procacci. “There is no need to waste words,” he wrote about the Castiglione Garfagnana and Parma altarpieces, “demonstrating that [Giuliano’s] art approaches that of Agnolo Gaddi, not only in its forms but also in its palette.”16 It was surprising, Procacci pointedly noted in the same context, that these works bore no traces of Spinello’s Lucchese production. Undoubtedly, the pastel hues and blonde tonalities that also distinguish the Yale Saints, along with the delicate flush of their cheeks, seem to have much more in common with Agnolo’s lyrically luminous paintings of the same decade—admittedly interpreted in a more prosaic vein—than with the “penumbral” qualities of Spinello’s San Ponziano polyptych, a work frequently compared to the Castiglione Garfagnana and Parma Madonnas.17 Equally unconvincing, however, is the pupil-master relationship proposed by some authors between Giuliano and Giovanni di Bartolomeo Cristiani, whose animated figures and “robust gothicism,” as it was defined by Zeri, find little reflection in the ephemeral, brittle elegance of the present image.18 The issue of Giuliano’s formation, predating the first mention of his name in documents in 1383 and 1386, remains an open question, although it seems fair to state that it was independent of Spinello and oriented instead toward Florentine painting in the previous decade.

Among the relatively few surviving fragments of large-scale altarpieces that can be securely attributed to Giuliano, only the Castiglione Garfagnana Virgin and Child is sufficiently similar to the Yale Saints to consider the possibility that they may originally have been included in the same complex. This hypothesis was tentatively advanced by Pisani in correspondence with the Yale University Art Gallery but was omitted in her later study of the painter, where the author seemed to opt for the alternative suggestion that the Virgin and Child may have been an independent image.19 As first noted by Procacci, the remains of the original frame around that work are, in fact, consistent with the central element of a larger structure. The dimensions of the Yale Saints, accounting for the modern framing elements, are sufficiently similar to those of the Castiglione Garfagnana panel to suggest that they could have stood to the left of the Virgin, in an arrangement comparable to Giuliano’s altarpieces at Moriano Castello and Lucca. Unfortunately, the transfer to canvas of the Yale panels precludes a comparison of their carpentry construction to that of the Castiglione Garfagnana panel, nor is it possible to contrast the tooling in the figures’ haloes, no longer discernible in the Virgin and Child. In the absence of other elements from the same structure, therefore, such a theory must for now be confined to the realm of pure speculation.

Nothing is known of the Castiglione Garfagnana Madonna prior to its first mention by the local historian Tommaso Trenta, in 1822, when it was already in the church of San Michele.20 There is no reason to assume, however, that the dismembered structure was originally intended for that location. The presence of a church dedicated to Saints Lawrence and Stephen in Cascio, located not far from Castiglione Garfagnana and subject to the monastery of San Ponziano, provides an intriguing opportunity for further research.21 —PP

Published References

van Marle, Raimond. The Development of the Italian Schools of Painting. Vol. 9. The Hague: M. Nijhoff, 1927., 198, fig. 132; Berenson, Bernard. Italian Pictures of the Renaissance, A List of the Principal Artists and Their Works with an Index of Places: The Florentine School. 2 vols. London: Phaidon, 1963., 1:140; Seymour, Charles, Jr. Early Italian Paintings in the Yale University Art Gallery. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1970., 50, 53, 309, no. 35; Gonzalez-Palacios, Alvar. “Percorso di Giuliano di Simone.” Arte illustrata 4, nos. 45–46 (1971): 49–59., 50, 51n17, fig. 11; Fredericksen, Burton B., and Federico Zeri. Census of Pre-Nineteenth-Century Italian Paintings in North American Public Collections. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1972., 600; Boskovits, Miklós. Pittura fiorentina alla vigilia del Rinascimento, 1370–1400. Florence: Edam, 1975., 247n236; Boggi, Flavio. Review of Sumptuosa tabula picta: Pittori a Lucca tra gotico e Rinascimento, ed. Maria Teresa Filieri. Renaissance Studies 12, no. 4 (1998): 564–73., 568; Linda Pisani, in Filieri, Maria Teresa, ed. Sumptuosa tabula picta: Pittori a Lucca tra gotico e Rinascimento. Exh. cat. Florence: Sillabe, 1998., 187, fig. 133; Labriola, Ada. “Giuliano di Simone.” In Dizionario biografico degli italiani. Rome: Istituto della Enciclopedia Italiana, 2001.

Notes

-

Franciotti, Cesare. Historie delle miracolose imagini, e delle vite de’ Santi, i corpi de’quali sono nella Città di Lucca. Lucca: Ottauiano Guidoboni, 1613., 297–308. ↩︎

-

Curatorial files, Department of European Art, Yale University Art Gallery. ↩︎

-

Lecture notes recorded in the Frick Art Reference Library, New York. ↩︎

-

Curatorial files, Department of European Art, Yale University Art Gallery. ↩︎

-

“You might compare them,” the letter continues, “with the two saints in the Boston Museum which Perkins published in Art in America, December 1921.” The two saints referred to by van Marle are the Saint Vincent and Saint Stephen now attributed to Starnina, in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, inv. nos. 20.1855a–b, https://collections.mfa.org/objects/35898/saint-vincent and https://collections.mfa.org/objects/31851/saint-stephen. Due to an editorial oversight, the 1927 edition of van Marle’s Development of the Italian Schools of Painting included a photograph of the Yale Saints where, according to the text, there should have been one of the Boston panels, resulting in some confusion among later scholars; see van Marle, Raimond. The Development of the Italian Schools of Painting. Vol. 9. The Hague: M. Nijhoff, 1927., 198, fig. 132. ↩︎

-

Verbal opinion, reported by Griggs, May 1926, recorded in the Frick Art Reference Library, New York. ↩︎

-

Berenson, Bernard. Italian Pictures of the Renaissance, A List of the Principal Artists and Their Works with an Index of Places: The Florentine School. 2 vols. London: Phaidon, 1963., 1:140. ↩︎

-

Seymour, Charles, Jr. Early Italian Paintings in the Yale University Art Gallery. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1970., 50, 53, no. 35. ↩︎

-

Unpublished opinion, March 18, 1965, recorded in the Frick Art Reference Library, New York. ↩︎

-

Gonzalez-Palacios, Alvar. “Percorso di Giuliano di Simone.” Arte illustrata 4, nos. 45–46 (1971): 49–59., 50, 51n17. ↩︎

-

Verbal opinion, August 3, 1998, recorded in the curatorial files, Department of European Art, Yale University Art Gallery. ↩︎

-

Although accepted as a possible early work of Giuliano by Boskovits (in Boskovits, Miklós. Pittura fiorentina alla vigilia del Rinascimento, 1370–1400. Florence: Edam, 1975., 247), the Pisa Virgin was definitively excluded from the artist’s oeuvre by Massimo Ferretti; see Ferretti, Massimo. “Una croce a Lucca, Taddeo Gaddi, un nodo di tradizione giottesca.” Paragone 27, nos. 317–19 (1976): 19–40., 40n25. For Luciano Bellosi, the Pisa panel was “among the most important works in the following of Traini”; see Bellosi, Luciano. “Sur Francesco Traini.” Revue de l’art 92 (1991): 9–19., 17. In her recent monograph on Traini, Linda Pisani convincingly identified the painting as an early work of the so-called Maestro della Carità, a Pisan contemporary of Traini; see Pisani, Linda. Francesco Traini e la pittura a Pisa nella prima metà del trecento. Cinisello Balsamo, Milan: Silvana, 2020., 81–82. ↩︎

-

Linda Pisani, in Filieri, Maria Teresa, ed. Sumptuosa tabula picta: Pittori a Lucca tra gotico e Rinascimento. Exh. cat. Florence: Sillabe, 1998., 187, fig. 133; and Labriola, Ada. “Giuliano di Simone.” In Dizionario biografico degli italiani. Rome: Istituto della Enciclopedia Italiana, 2001.. ↩︎

-

Inv. no. 1946.15; see Labriola, Ada. “Giuliano di Simone.” In Dizionario biografico degli italiani. Rome: Istituto della Enciclopedia Italiana, 2001.. ↩︎

-

Procacci, Ugo. “Opere sconosciute d’arte Toscana—I.” Rivista d’arte 14 (1932): 341–53, 463–75., 346, where he cites Offner’s unpublished opinion. ↩︎

-

“Non importa spendere molte parole per dimostrare che la sua arte si avvicina a quella di Agnolo Gaddi, e non solo per le forme ma anche per una simile tendenza coloristica”; author’s translation. After discussing the distinctions between Giuliano’s idiom and that of Angelo Puccinelli, Procacci went on to add that it was “strange” how the work of both painters bore no evidence of Spinello’s presence in Lucca: “Quel che è strano è come nelle pitture dei due maestri non si risenta niente dell’arte di Spinello Aretino”; see Procacci, Ugo. “Opere sconosciute d’arte Toscana—I.” Rivista d’arte 14 (1932): 341–53, 463–75., 46. The relevance of Agnolo Gaddi’s production for the Castiglione Garfagnana Madonna and the Parma panel was reiterated by Ada Labriola, notwithstanding her late dating of the Yale Saints; see Labriola, Ada. “Giuliano di Simone.” In Dizionario biografico degli italiani. Rome: Istituto della Enciclopedia Italiana, 2001.. ↩︎

-

In his discussion the San Ponziano polyptych, Angelo Tartuferi evocatively referred to the “piglio ombroso” that distinguished that work as a result of its pronounced chiaroscuro modeling; see Tartuferi, in Filieri, Maria Teresa, ed. Sumptuosa tabula picta: Pittori a Lucca tra gotico e Rinascimento. Exh. cat. Florence: Sillabe, 1998., 140, no. 2. Alvar Gonzalez-Palacios was the first author to emphasize the perceived impact of Spinello’s Lucchese production on Giuliano, and the relevance of the San Ponziano polyptych in particular; see Gonzalez-Palacios, Alvar. “Percorso di Giuliano di Simone.” Arte illustrata 4, nos. 45–46 (1971): 49–59., 49–59. Since then, it has become a leitmotif of most discussions of the artist. ↩︎

-

Zeri, Federico. “Appunti nell’Ermitage e nel Museo Pusckin.” Bollettino d’arte 46, no. 3 (July–September 1961): 219–36., 220. ↩︎

-

Linda Pisani, November 10, 1996, curatorial files, Department of European Art, Yale University Art Gallery; and Linda Pisani, in Filieri, Maria Teresa, ed. Sumptuosa tabula picta: Pittori a Lucca tra gotico e Rinascimento. Exh. cat. Florence: Sillabe, 1998., 187. Gonzalez-Palacios’s proposal that a fragment with Saint Catherine of Alexandria formerly in the church of San Frediano, Lucca, should be associated with the same altarpiece was correctly rejected by Pisani on stylistic grounds. See Alvar Gonzalez-Palacios, in Filieri, Maria Teresa, ed. Sumptuosa tabula picta: Pittori a Lucca tra gotico e Rinascimento. Exh. cat. Florence: Sillabe, 1998., 22; and Linda Pisani, in Filieri, Maria Teresa, ed. Sumptuosa tabula picta: Pittori a Lucca tra gotico e Rinascimento. Exh. cat. Florence: Sillabe, 1998., 192–93, 198–99, nos. 13, 16. ↩︎

-

Trenta, Tommaso. Memorie e documenti per servire all’istoria del ducato di Lucca. Vol. 8, Dissertazione sullo stato dell’architettura, pittura e arti. Lucca: Bertini, 1822., 31. ↩︎

-

The church of Saints Lawrence and Stephen in Cascio was entrusted to the care of the monastery of San Ponziano in 1358; see Angelini, Lorenzo. Storia e arte in Garfagnana. Lucca: Pacini Fazzi, 2009., 15. ↩︎