Alfonso Tacoli-Canacci (1724–1801), Florence, 1789–92; from whom probably purchased by Ferdinando di Borbone (1751–1802), duke of Parma and Piacenza, 1792; Cesare Canessa (1863–1922) and Ercole Canessa (1868–1929) Collection, New York and Paris; sale, American Art Galleries, New York, January 25–26, 1924, lot 162; Maitland Fuller Griggs (1872–1943), New York, 1924

The panel support, of a horizontal grain, has been thinned to 11 millimeters, cradled, and waxed. It is comprised of three planks with seams on a slight diagonal: 20 centimeters from the top at the right and 20.6 centimeters from the top at the left; 25.5 centimeters from the bottom at the right and 27 centimeters from the bottom at the left. Movement along the lower seam has provoked modest paint loss and retouching along its full length, but the upper seam has barely disturbed the paint surface. Pressure from the cradle has caused several partial splits across the length of the top plank, mostly within 5 centimeters of its lower edge, and minor paint loss. Both the center and bottom planks have partial splits at their right edges, but these have resulted in no appreciable paint loss. Evidence of a barb is present along all four edges of the composition. The gilding and paint surface are in excellent state, outside of minor, if clumsy, retouching to the faces of the upper two angels on the right side and some reinforcement of the green draperies of the angel kneeling below them. Minor flaking of the pink draperies and wings of the upper pair of angels where they overlap the gold ground have not been retouched. The silver leaf used in the sgraffito decoration of the cloth of honor appears to have been laid atop the gold ground, which is exposed in one area of abrasion to the right of Saint Lucy and again alongside her halo at the top where the squares of silver leaf were not cut to the full width and height of the field they were meant to cover.

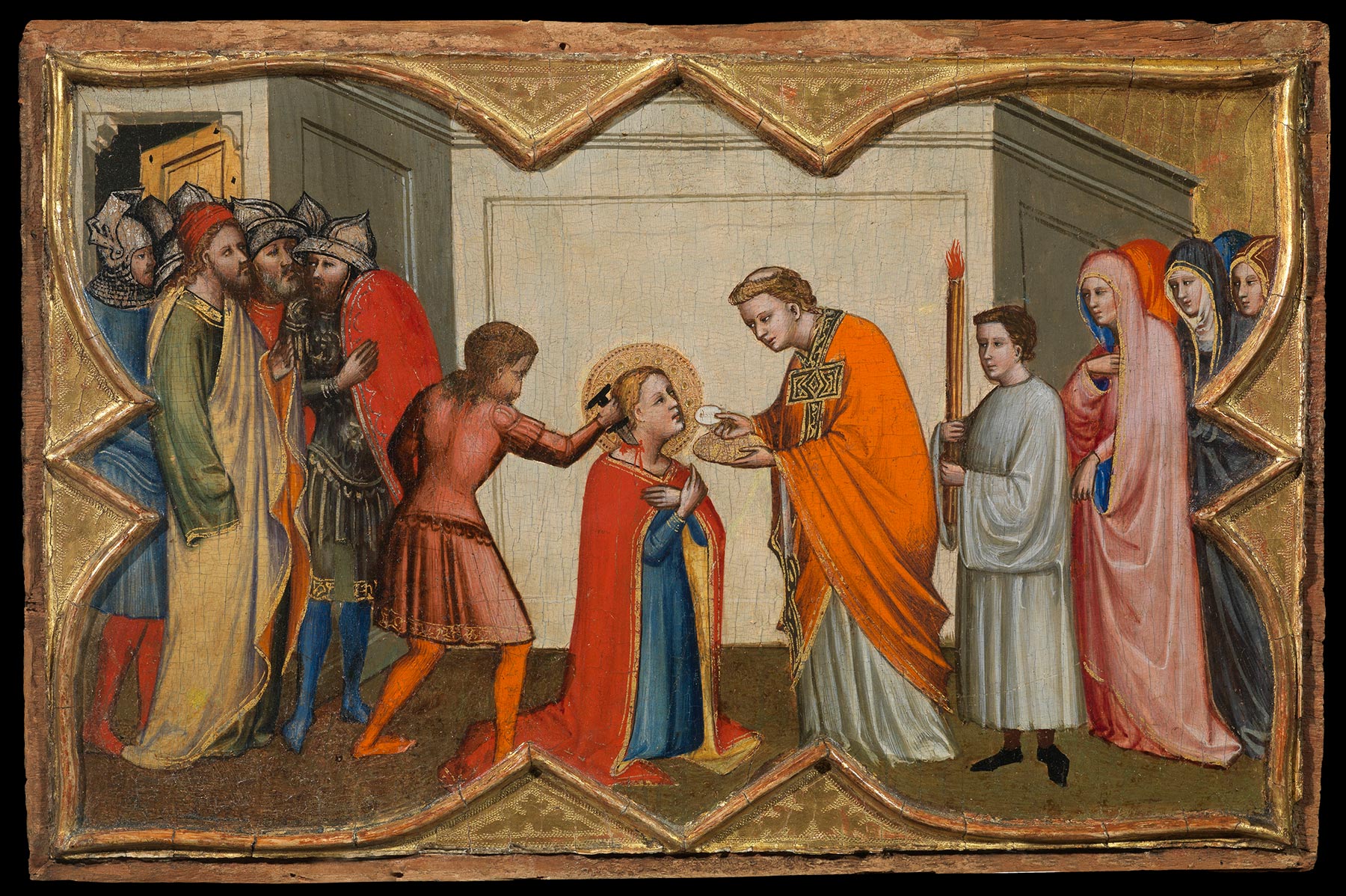

The panel, in near-perfect condition, shows Saint Lucy in glory surrounded by singing and music-making angels. The young saint, martyred in Syracuse, Sicily, in the year 303 or 304 C.E., is identified by the dagger with which she was executed, in her right hand, and a burning lamp—the flame now no longer visible—in her left. The attribute of the lamp, more common in early representations of the saint, was an allusion to the etymology of her name, Lucia, derived from the Latin word for light (lux) and interpreted in terms of her spiritual guidance as the “way of light” and “light of truth.”1 Dressed in a royal-red cape trimmed in gold over a blue tunic, the saint is seated on a throne covered by an elaborately embroidered cloth of honor held up by two angels in the background. Two more angels, kneeling at her side in the middle ground, sing her praise to the accompaniment of another pair of angels, in the foreground—one playing a harp, the other a vielle. The image was originally the central element of a large dossal, dismembered probably in the eighteenth century, that also included six episodes from the life of Saint Lucy (fig. 1), arranged in two columns of three each, one to the left and one to the right of the present panel. Four of the scenes, now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, depict, in narrative sequence, Saint Lucy and Her Mother at the Shrine of Saint Agatha (fig. 2); Saint Lucy Giving Alms (fig. 3); Saint Lucy before the Prefect Paschasius (fig. 4); and Saint Lucy Resisting Efforts to Move Her (fig. 5). A fifth panel, formerly in the Alana Collection, Newark, Delaware, shows the Last Communion and Martyrdom of Saint Lucy (fig. 6).2 Completing the series was an image of the Funeral of Saint Lucy, last recorded in the early nineteenth century in the Paris collection of Timothée Francillon (1766–1829) and known only through an engraving.

The earliest mention of the Yale Saint Lucy, as recently discovered by Vincenzo Buonocore, is in the 1789, 1790/91, and 1792 inventories of the eighteenth-century collector and dealer Marchese Alfonso Tacoli-Canacci, where it is described in precise detail as “a painting on gold leaf showing Saint Lucy seated on a throne with a dagger in the right hand and a vase with a flame in the left, and six angels on the sides; two of whom in the act of playing the harp and the violin . . . by Simone Memmi [Martini] celebrated by Petrarch.”3 Intended as sale catalogues, the three inventories were compiled by Tacoli-Canacci shortly after his transfer from Parma to Florence in 1785, at the height of the Leopoldine suppressions of monasteries and other religious institutions, a period that he described as most “felicitous” for his acquisition of works of art. The 1792 inventory, now preserved in the Archivio di Stato di Parma, comprises all of the paintings then being offered for sale to Don Ferdinando di Borbone, duke of Parma and Piacenza, possibly indicating that the Yale panel, which is not mentioned in subsequent catalogues of the marchese’s collection, was acquired by the duke along with his numerous other purchases from the same list.4

There is no further record of the Yale Saint Lucy until its appearance on the art market in 1924, when it was included in the American Art Galleries, New York, sale of the collection of Cesare and Ercole Canessa—Neapolitan art dealers with branches in both Paris and New York—and was purchased by Maitland Griggs.5 By this date, the painting was listed with an attribution to Giovanni di Bartolomeo Cristiani, subsequently reiterated by Richard Offner in a lecture at the Griggs residence in 1925.6 On this occasion, Offner added the Yale painting to the first nucleus of works gathered around the artist’s signed and dated 1370 dossal with Saint John the Evangelist in the church of San Giovanni Fuorcivitas, Pistoia. The small grouping included the four episodes from the life of Saint Lucy in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, then regarded as elements of a predella; a pinnacle fragment with Christ in Glory formerly in the Ehrich Galleries, New York (current location unknown); and an altarpiece in the Acton Collection at Villa La Pietra, Florence. Although Raimond van Marle, in correspondence with Griggs,7 offered a different opinion and assigned the Yale Saint Lucy to a so-called Compagno dell’Orcagna—now identified as Nardo di Cione—subsequent scholarship, beginning with Bernard Berenson, embraced Offner’s attribution to Cristiani.8 In 1961, writing to Hellmut Wohl, then in the Department of the History of Art at Yale, Federico Zeri first identified the Yale panel as part of the same complex as the stories of Saint Lucy in the Metropolitan Museum, suggesting a structure similar to the Saint John the Evangelist dossal in Pistoia.9 Zeri later added the ex-Alana panel, then in the Heinz Kisters collection, in Kreuzlingen, Switzerland, to his reconstruction,10 which was reiterated by Charles Seymour, Jr.11 The original appearance of the dossal was finally confirmed by Michel Laclotte, who recognized the missing sixth panel in the series, the Funeral of Saint Lucy, among the engravings in Francillon’s 1823 French translation of Luigi Lanzi’s Storia pittorica dell’Italia, illustrated primarily by works from Francillon’s own collection.12

Most modern scholarship has placed the execution of the Saint Lucy dossal in the 1370s, following Cristiani’s Saint John the Evangelist altarpiece but preceding the artist’s frescoes with Dominican allegories in the church of San Domenico, Pistoia, generally placed in the following decade. The evaluation of Cristiani’s activity has been significantly altered, however, by Giacomo Guazzini’s discussion of several of the painter’s most important works, including the present one, within the context of the patronage of the Dominican preacher and theologian Andrea Franchi (1335–1401), bishop of Pistoia between 1381/83 and 1400.13 Following an early intuition of Viktor Schmidt,14 Guazzini traced the original provenance of the Saint Lucy dossal to the Dominican female convent of Saint Lucy in Pistoia and suggested that the commission had been awarded to Cristiani by Franchi in the early 1380s, around the same time that the prelate was involved in various restoration projects for the monks of San Domenico. The convent of Saint Lucy, built in 1335 and destroyed in 1539, was a close dependency of San Domenico, which enjoyed the special patronage of Franchi, who was prior of the monastery in the 1370s and was buried in its church. Among the first commissions of Franchi, whose coat of arms appears on the facade of San Domenico, was a rebuilding campaign that also involved the decoration of the church’s interior with Cristiani’s cycle of Dominican allegories, originally located on the left side of the nave (detached in 1946, now in the refectory of San Domenico). As Guazzini concluded, it is not unlikely that the bishop would have extended his munificence to the small sister community of Saint Lucy, which also came under his protection and which he reportedly endowed with various testamentary bequests.

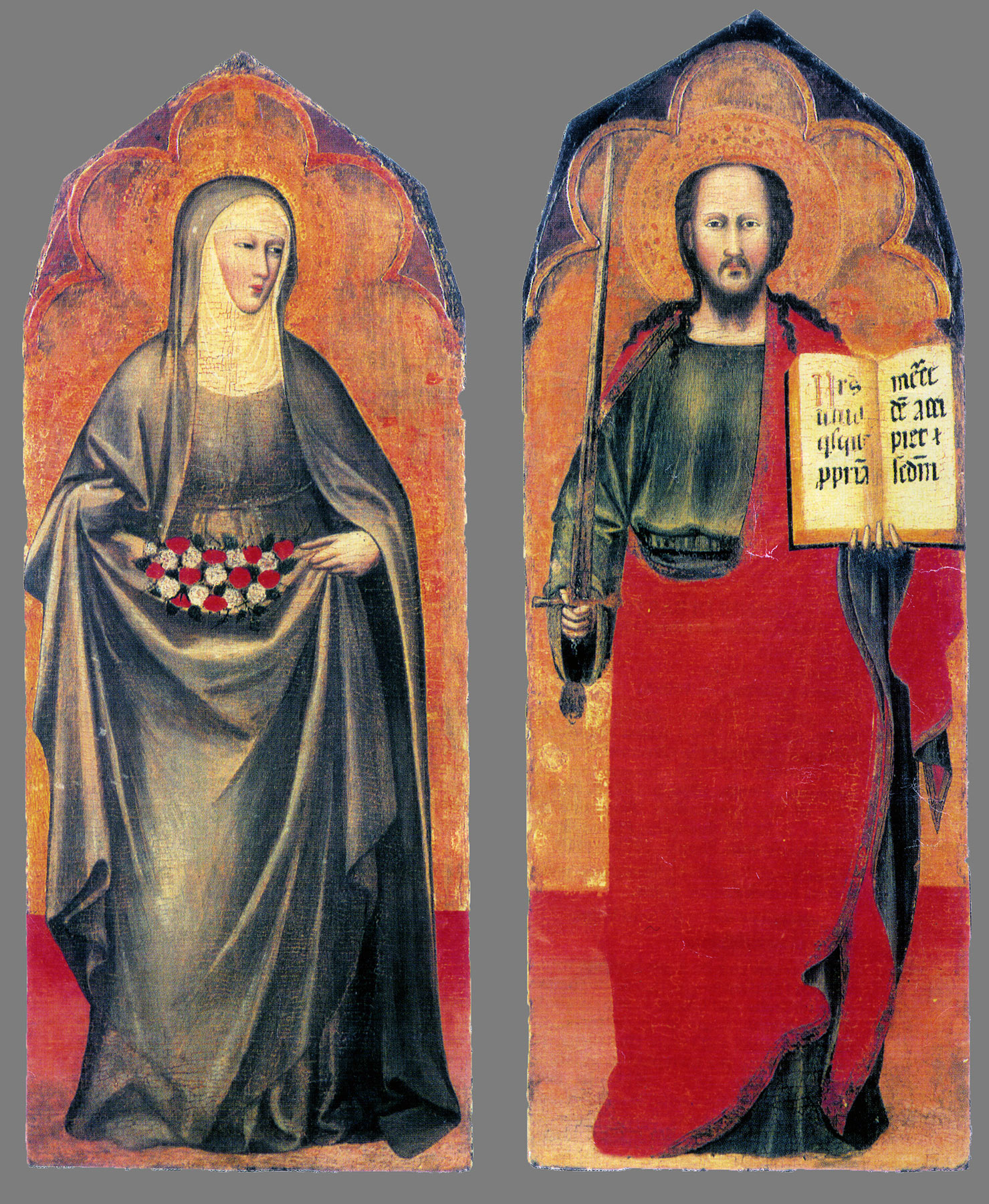

Beyond the entirely plausible circumstantial evidence for a dating after 1380, stylistic elements also suggest a much later chronology for the Saint Lucy dossal than previously supposed. A comparison of the small scenes that originally flanked the Yale Saint Lucy with those in the Saint John the Evangelist dossal reveals a significant evolution in the artist’s idiom away from the Orcagnesque models of the 1370s, toward a more lively, looser narrative vocabulary that seems much more attuned to the developments of Late Gothic painting in Florence in the generation following the Cione. As noted by Berenson in reference to the Yale Saint Lucy, “here Cristiani brings more to mind Agnolo than the Orcagna.”15 The elongated proportions and pinched features of the saint and her attendant angels, as well as the pastel tonalities, have much in common, in fact, with the vocabulary of provincial imitators of Agnolo Gaddi, such as the Lucchese painter Giuliano di Simone, whose work has sometimes been confused with Cristiani’s (see Giuliano di Simone, Two Deacon Saints). This gradual evolution in the artist’s approach, beginning with the San Domenico frescoes, also characterizes two other works by Cristiani, both of which were dated by Guazzini to the same decade based on circumstantial evidence: the polyptych currently divided between the Pushkin Museum, Moscow,16 the State Hermitage Museum, Saint Petersburg,17 and the Museo Bandini, Fiesole,18 possibly commissioned by Bartolomeo Franchi (1340–1405), Andrea’s younger brother, for the Olivetan monastery of San Benedetto, Pistoia, founded by him around 1380; and the altarpiece in the Acton Collection, Florence, whose provenance Guazzini has traced to the Augustinian monastery of Santa Maria della Neve in Pistoia, consecrated in 1380.19 While closely related to these images, however, the Yale Saint Lucy is marked by a drier execution and less nuanced handling of forms that point to a slightly later moment in the artist’s activity. Its execution must be virtually contemporary to that of the two panels with Saint Paul and Saint Elizabeth of Hungary first recorded in the collection of John Temple Leader (1810–1903) in the Castello di Vincigliata, Fiesole, and subsequently in the Fassini collection, Rome (fig. 7). Surviving fragments of a hitherto unidentified polyptych, they were dated by Miklós Boskovits between 1385 and 1390, a time frame that is also applicable to the present work.20 —PP

Published References

American Art Galleries, New York. Illustrated Catalogue of the Art Collection of the Expert Antiquarians C. & E. Canessa of New York, Paris, Naples. Sale cat. January 25–26, 1924., lot 162; Berenson, Bernard. “Quadri senza casa: Il trecento fiorentino, III.” Dedalo 11 (1930–31): 1286–318., 1312, 1314; Comstock, Helen. “The Yale Collection of Italian Paintings.” Connoisseur 118 (September 1946): 45–52., 48; Kaftal, George. Iconography of the Saints in Tuscan Painting. Florence: Sansoni, 1952., col. 644, no. 192i; Offner, Richard. “A Ray of Light on Giovanni del Biondo and Niccolò di Tommaso.” Mitteilungen des Kunsthistorischen Institutes in Florenz 7, nos. 3–4 (July 1956): 173–92., 192; Berenson, Bernard. Italian Pictures of the Renaissance, A List of the Principal Artists and Their Works with an Index of Places: The Florentine School. 2 vols. London: Phaidon, 1963., 1:51, pl. 328; Seymour, Charles, Jr. Early Italian Paintings in the Yale University Art Gallery. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1970., 60–63, no. 42; Zeri, Federico, with Elizabeth E. Gardner. Italian Paintings: A Catalogue of the Collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art; Florentine School. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1971., 39; Fredericksen, Burton B., and Federico Zeri. Census of Pre-Nineteenth-Century Italian Paintings in North American Public Collections. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1972., 600; Boskovits, Miklós. Pittura fiorentina alla vigilia del Rinascimento, 1370–1400. Florence: Edam, 1975., 317–18; Offner, Richard. A Critical and Historical Corpus of Florentine Painting: The Fourteenth Century. Supplement: A Legacy of Attributions. Ed. Hayden B. J. Maginnis. New York: Institute of Fine Arts, New York University, 1981., 65; Boskovits, Miklós. “Cristiani, Giovanni.” In Dizionario biografico degli italiani. Rome: Istituto della Enciclopedia Italiana, 1985.; Freuler, Gaudenz. “Manifestatori delle cose miracolose”: Arte italiana del ’300 e ’400 da collezioni in Svizzera e nel Liechtenstein. Exh. cat. Lugano-Castagnola, Switzerland: Fondazione Thyssen-Bornemisza, 1991., 200–201; Kenney, Elise K., ed. Handbook of the Collections: Yale University Art Gallery. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1992., 133; Skaug, Erling S. Punch Marks from Giotto to Fra Angelico: Attribution, Chronology, and Workshop Relationships in Tuscan Panel Painting, with Particular Consideration to Florence, c. 1330–1430. 2 vols. Oslo: International Institute for Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works—Nordic Group, 1994., 1:152, 2: pl. 6.5; Frinta, Mojmír S. Punched Decoration on Late Medieval Panel and Miniature Painting. Vol. 1, Catalogue Raisonné of All Punch Shapes. Prague: Maxdorf, 1998., 50, 234, 513; Laclotte, Michel. “N’en déplaise à Cicognara: La collection Francillon.” In Curiosité: Études d’histoire de l’art en l’honneur d’Antoine Schnapper, ed. Olivier Bonfait, Véronique Gerard Powell, and Philippe Sénéchal, 415–23. Paris: Flammarion, 1998., 418, fig. 150; Buonocore, Vincenzo M. Il marchese Alfonso Tacoli-Canacci: “Onesto gentiluomo smaniante per la Pittura.” Reggio Emilia: Società Reggiana di Studi Storici, 2005., 100, 139–40, no. 23, fig. 66; Galli, Aldo. “Tavole toscane del tre e quattrocento nella collezione di Alfonso Tacoli Canacci.” In Invisibile agli occhi: Atti della giornata di studio in ricordo di Lisa Venturini, ed. Nicoletta Baldini, 13–28. Florence: Fondazione di Studi di Storia dell’Arte Roberto Longhi, 2007., 20, 26–27n53, fig. 21; Schmidt, Victor M. “Ensembles of Painted Altarpieces and Frontals.” In The Altar and Its Environment, 1150–1400, ed. Justin E. A. Kroesen and Victor M. Schmidt, 203–21. Studies in the Visual Cultures of the Middle Ages 4. Turnhout, Belgium: Brepols, 2009., 209, 303, pl. 66, fig. 8; Guazzini, Giacomo. “Commissioni artistiche tra Prato e Pistoia, anno 1400: Un’apertura per il vescovo Andrea Franchi ed il fratello Bartolomeo.” In Officina pratese: Tecnica, stile, storia, ed. Paolo Benassai, Marco Ciatti, Andrea de Marchi, Cristina Gnoni Mavarelli, and Isabella Lapi Ballerini, 211–28. Florence: Edifir, 2014., 212, 224nn12–14

Notes

-

The attribute of the burning lamp was gradually replaced in the course of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries with that of a salver displaying the saint’s eyes. This iconographic development, which led to her role as patron saint of eyesight, has been traced to a later legend, of unknown origin and distinct from the Golden Legend, that told of Lucy’s self-blinding to repel the advances of a suitor and preserve her virginity; see Wisch, Barbara. “Seeing Is Believing: St. Lucy in Text, Image, and Festive Culture.” In The Saint between Manuscript and Print: Italy, 1400–1600, ed. Alison K. Frazier, 101–41. Toronto: Center for Reformation and Renaissance Studies, 2015., 101–41. ↩︎

-

The painting was sold at Christie’s, New York, June 9, 2022, lot 34. ↩︎

-

Buonocore, Vincenzo M. Il marchese Alfonso Tacoli-Canacci: “Onesto gentiluomo smaniante per la Pittura.” Reggio Emilia: Società Reggiana di Studi Storici, 2005., 139–40. The same attribution to “Simone Memmi” is registered for both the ex-Alana Collection and ex-Francillon panels with stories from the life of Saint Lucy, leading some scholars to speculate whether Tacoli-Canacci might have owned the entire dossal and dismembered it for individual sale; see Galli, Aldo. “Tavole toscane del tre e quattrocento nella collezione di Alfonso Tacoli Canacci.” In Invisibile agli occhi: Atti della giornata di studio in ricordo di Lisa Venturini, ed. Nicoletta Baldini, 13–28. Florence: Fondazione di Studi di Storia dell’Arte Roberto Longhi, 2007., 27n56. ↩︎

-

Archivio di Stato di Parma, MS 101; see Buonocore, Vincenzo M. Il marchese Alfonso Tacoli-Canacci: “Onesto gentiluomo smaniante per la Pittura.” Reggio Emilia: Società Reggiana di Studi Storici, 2005., 71–72, 91, 100. ↩︎

-

For a history of the Canessa firm and its various branches, see D’Orazi, Luca. Canessa: Una famiglia di antiquari. Nummus et historia 35. Cassino: Libreria Classica Editrice Diana, 2018.. ↩︎

-

Lecture notes recorded in the Frick Art Reference Library, New York. ↩︎

-

Correspondence dated February 1, 1926, Frick Art Reference Library, New York. ↩︎

-

Berenson, Bernard. “Quadri senza casa: Il trecento fiorentino, III.” Dedalo 11 (1930–31): 1286–318., 1312, 1314. ↩︎

-

A copy of the letter, which is dated March 2, 1961, is in the Frick Art Reference Library, New York. ↩︎

-

Zeri, Federico, with Elizabeth E. Gardner. Italian Paintings: A Catalogue of the Collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art; Florentine School. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1971., 39. ↩︎

-

Seymour, Charles, Jr. Early Italian Paintings in the Yale University Art Gallery. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1970., 60–63, no. 42. ↩︎

-

Laclotte, Michel. “N’en déplaise à Cicognara: La collection Francillon.” In Curiosité: Études d’histoire de l’art en l’honneur d’Antoine Schnapper, ed. Olivier Bonfait, Véronique Gerard Powell, and Philippe Sénéchal, 415–23. Paris: Flammarion, 1998., 418, fig. 150. ↩︎

-

Guazzini, Giacomo. “Commissioni artistiche tra Prato e Pistoia, anno 1400: Un’apertura per il vescovo Andrea Franchi ed il fratello Bartolomeo.” In Officina pratese: Tecnica, stile, storia, ed. Paolo Benassai, Marco Ciatti, Andrea de Marchi, Cristina Gnoni Mavarelli, and Isabella Lapi Ballerini, 211–28. Florence: Edifir, 2014., 212, 224nn12–14. ↩︎

-

Schmidt, Victor M. “Ensembles of Painted Altarpieces and Frontals.” In The Altar and Its Environment, 1150–1400, ed. Justin E. A. Kroesen and Victor M. Schmidt, 203–21. Studies in the Visual Cultures of the Middle Ages 4. Turnhout, Belgium: Brepols, 2009., 209, 303, pl. 66, fig. 8. ↩︎

-

Berenson, Bernard. “Quadri senza casa: Il trecento fiorentino, III.” Dedalo 11 (1930–31): 1286–318., 1312. ↩︎

-

Inv. no. 176. ↩︎

-

Inv. nos. 271, 274. ↩︎

-

Inv. nos. 15, 17. ↩︎

-

Guazzini, Giacomo. “Commissioni artistiche tra Prato e Pistoia, anno 1400: Un’apertura per il vescovo Andrea Franchi ed il fratello Bartolomeo.” In Officina pratese: Tecnica, stile, storia, ed. Paolo Benassai, Marco Ciatti, Andrea de Marchi, Cristina Gnoni Mavarelli, and Isabella Lapi Ballerini, 211–28. Florence: Edifir, 2014., 215–16, 220–21. ↩︎

-

Boskovits, Miklós. Pittura fiorentina alla vigilia del Rinascimento, 1370–1400. Florence: Edam, 1975., 319. The earliest reference to these works is in the nineteenth-century guide to the castle of Vincigliata, published by a close friend (and possibly relative) of John Temple Leader, Lucy Baxter, under the pseudonym Leader Scott; see Scott, Leader [Lucy Baxter]. Vincigliata and Maiano. London: T. Fisher Unwin, 1891., 113, nos. 6–7. At this date, the Saint Elizabeth was largely repainted to look like Saint Lucy (though described by Scott as a “Saint Christine”). The castle of Vincigliata and its entire contents were purchased by Baron Alberto Fassini in 1917. After the sale of the property in 1925, some of the objects collected by Leader went on to form the nucleus of Fassini’s collection in his residence in Rome; see Baldry, Francesca. John Temple Leader e il castello di Vincigliata: Un episodio di restauro e di collezionismo nella Firenze dell’ottocento. Fondazione Carlo Marchi 9. Florence: Leo S. Olschki, 1997., 160–61n195, 192n12. Among them were the Saint Paul and Saint Elizabeth, which underwent restoration sometime before the publication of the catalogue of the Fassini collection in 1930, where they were attributed by Adolfo Venturi to Niccolò di Tommaso; see Venturi, Adolfo. Collezione d’arte del barone Alberto Fassini. 3 vols. Milan: Bestetti and Tumminelli, 1930., 1: pls. 5–6. The panels were first recognized as works of Cristiani by Richard Offner in 1924 (recorded in the Frick Art Reference Library, New York) and by Berenson in Berenson, Bernard. “Quadri senza casa: Il trecento fiorentino, III.” Dedalo 11 (1930–31): 1286–318., 1318n8. Records in the Fototeca Zeri, Federico Zeri Foundation, Bologna, inv. no. 6957, note that they last appeared in a sale at Finarte, Milan (date not given). ↩︎