Maitland Fuller Griggs (1872–1943), New York, by 1925

Both this panel and the related Saint Catherine of Alexandria; Saint Lawrence, of a vertical wood grain, are 1.3 centimeters thick, and neither has been thinned or cradled. Saint Catherine was radically cleaned in 1968. Saint Nicholas has not been cleaned; its reverse is impregnated with wax, obscuring evidence of original structural supports that might be present there. It has developed two partial splits rising from the bottom, one 12.2 centimeters from the right edge and 18 centimeters long, the other 26.5 centimeters from the right edge and 35 centimeters long. The panel with Saint Catherine has a minor split at the bottom, 13.5 centimeters from the left edge and rising only 4.5 centimeters. That panel appears to have had three battens affixed to it: one approximately 6 centimeters wide, trimmed along the bottom edge of the panel; one approximately 7 centimeters wide, 53 centimeters above the lower batten; and one of the same width, 54 centimeters above the center batten. The surface of the reverse between the battens appears to have been coated with paper or parchment beneath a thin application of gesso. The engaged frame moldings on the front of the panel are wood, much deteriorated from insect damage, 1-centimeter deep along the left side and bottom and 1.3-centimeters deep along the gable. The molding along the right side is missing; the molding along the left side overhangs the edge of the panel to cover the seam that once joined it to the adjacent center panel of the altarpiece. The 8-millimeter-thick molding defining the ogival arch above the head of Saint Catherine is molded in gesso or stucco. On the panel with Saint Nicholas, the frame moldings applied cross-grain are wood; the vertical moldings and the ogival arch are molded in gesso or stucco (except for the capitals and bases, which are carved). The fixed molding along the left edge of the panel indicates that Saint Nicholas was originally the left-most lateral of the altarpiece; the molding along the right edge is missing.

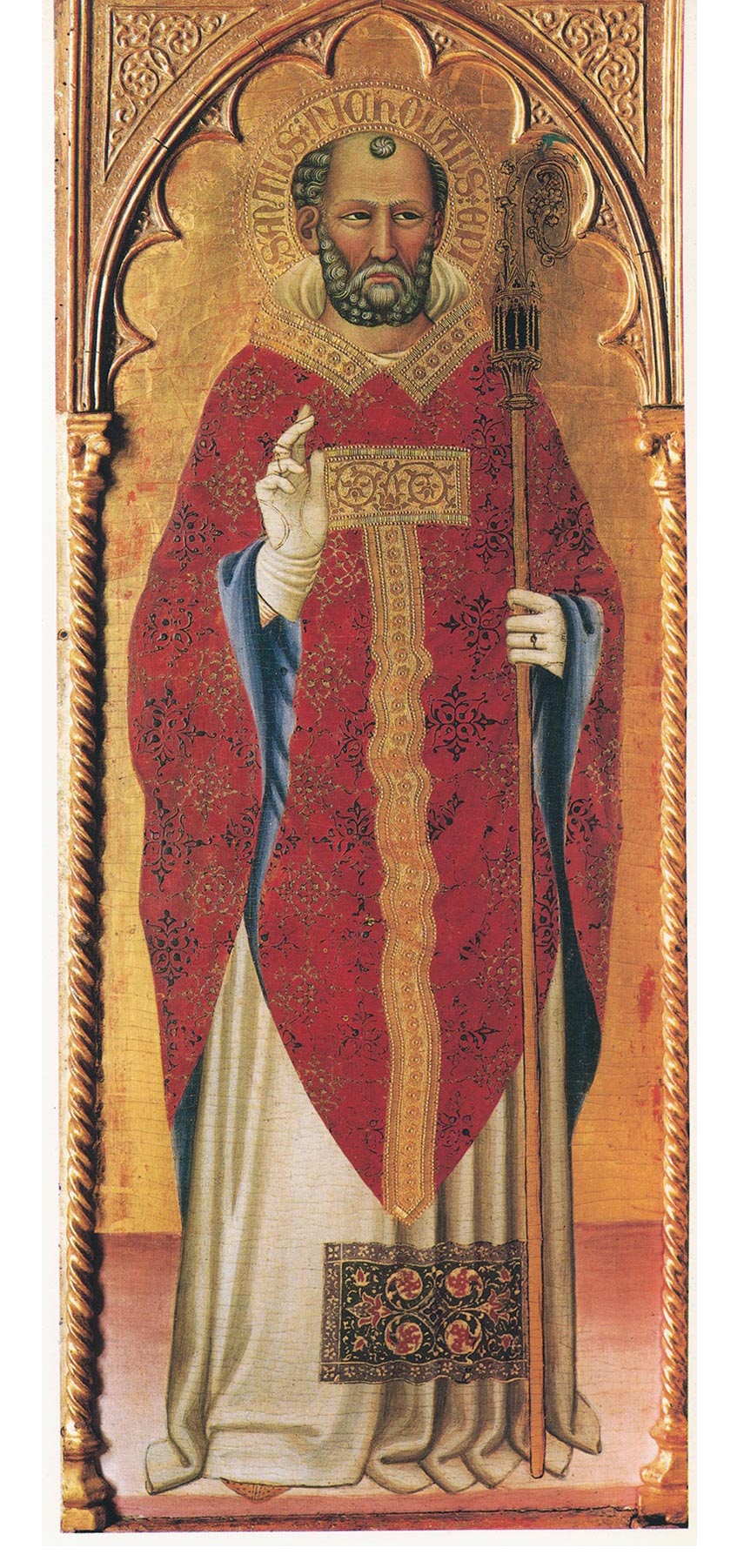

The paint surface of the Saint Nicholas is dulled by a thick and heavily discolored varnish but is essentially in very good condition, except for the lower 14 centimeters, which are eighteenth- or nineteenth-century restorations in oil defining the pavement, the saint’s shoes, and his white surplice. The gilt hem of his cope directly bordering this area is largely repaired, as is a hole in the saint’s left upper arm, but retouching otherwise is confined to inpainting small flaking losses. The Saint Catherine has similarly suffered extensive losses along its lower 14 centimeters, obliterating the saint’s feet and the lower part of her dress. This panel also exhibits large losses where the nails securing the central batten were excavated and removed, as well as in the martyr’s palm and in the elbow of Saint Lawrence in the gable, where flaking losses were enlarged by harsh cleaning. The red lining of Saint Catherine’s cloak is heavily abraded, as are the blue shadows in draperies—where a modulating glaze seems to have been removed—and the skin tones throughout, where shadows have been worn to the priming layer. The gold ground in this panel is evenly abraded, with larger losses around punch strikes sunk deep in the thicker-than-usual gesso substrate.

This standing saint and the related Saint Catherine of Alexandria; Saint Lawrence were once the laterals of an unidentified altarpiece. Based on the figures’ glances and slight turns of the heads, coupled with differences in the design and application of the frame moldings on each panel, it is probable that Saint Nicholas of Bari originally stood on the left end of the structure, while Saint Catherine of Alexandria stood on the right of the central compartment. The representation of Saint Nicholas of Bari conforms to the traditional Byzantine type, without a bishop’s hat and holding a book and crozier. He wears a red chasuble decorated with the episcopal pallium over a gilt-edged blue dalmatic and white tunic. In the pinnacle above him is a saint in Franciscan habit holding a book, most likely Saint Anthony of Padua. Saint Catherine of Alexandria, identified by her usual attributes, the crown and wheel of martyrdom, wears a yellow mantle brocaded in gold and lined in red over the same color tunic. Above her is a deacon saint dressed in a red dalmatic, one hand raised in blessing, the other supporting a eucharistic cup. He is probably Saint Lawrence, who is traditionally identified by the grill of his martyrdom but sometimes also holds a chalice filled with wafers—a reference to the legend that he saved the holy cup used at the Last Supper from Roman seizure.1

The two panels, acquired by Maitland Griggs sometime before 1925, have been largely ignored by modern scholarship. According to notes in the Frick Art Reference Library, New York, Richard Offner discussed them in a lecture at the Griggs residence on January 19, 1925, when he referred to them as products of the fifteenth-century Florentine School, “out of the tradition of Bernardo Daddi.” Bernard Berenson first published the Saint Catherine panel in his 1932 volume of Italian paintings, under Martino di Bartolomeo, but omitted both works from his subsequent lists.2 The attribution to Martino di Bartolomeo was tentatively taken up by Charles Seymour, Jr., who proposed a date around 1415.3 Burton Fredericksen and Federico Zeri cited the attribution to Martino di Bartolomeo, although Zeri classified the panels in his photo archive among anonymous fifteenth-century Ligurian works.4 Based on some of the punchwork, derived from Francesco Traini, Mojmír Frinta referred to the Yale Saint Nicholas as “Pisan (or Genoese?).”5

The disparate opinions and some of the perplexities elicited by the Yale panels are undoubtedly due to their unique quality, from the peculiarity of some of the framing elements to the figural style. Efforts to insert them in the oeuvre of Martino di Bartolomeo are unconvincing and unsubstantiated by comparison with any of the master’s surviving production. Beyond technical correspondences, the most pertinent analogies are those with Pisan painting. As well as employing some of the same punch marks, the figure of Saint Nicholas, in particular, appears modeled on images painted by Francesco Traini and his contemporaries and by a later generation of Pisan artists, such as Cecco di Pietro (documented 1364–99) (fig. 1). The representation of Saint Catherine of Alexandria holding a diminutive wheel in her hand is also iconographically indebted to Trainesque examples. Absent from both panels, however, is the subtlety of execution of Traini’s immediate followers. Cecco di Pietro’s production in the late 1370s and 1380s, although distinguished by a more incisive, hard-edged approach, provides perhaps the most relevant point of reference for the Yale panels, but a localization in Ligurian territory, with its artistic dependance on Pisan models, cannot be ruled out.6 —PP

Published References

Berenson, Bernard. Italian Pictures of the Renaissance: A List of the Principal Artists and Their Works with an Index of Places. Oxford: Clarendon, 1932., 333; Seymour, Charles, Jr. Early Italian Paintings in the Yale University Art Gallery. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1970., 83, 311, nos. 57–58; Fredericksen, Burton B., and Federico Zeri. Census of Pre-Nineteenth-Century Italian Paintings in North American Public Collections. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1972., 600; Frinta, Mojmír S. Punched Decoration on Late Medieval Panel and Miniature Painting. Vol. 1, Catalogue Raisonné of All Punch Shapes. Prague: Maxdorf, 1998., 41, 419, nos. Aa13, Aa15b, Jd51

Notes

-

The saint is shown stepping on a grill and holding a large chalice filled with Communion wafers in a triptych by Lorenzo Monaco and his workshop in the Museé du Petit Palais, Avignon, France, inv. no. M.I.430. ↩︎

-

Berenson, Bernard. Italian Pictures of the Renaissance: A List of the Principal Artists and Their Works with an Index of Places. Oxford: Clarendon, 1932., 333. ↩︎

-

Seymour, Charles, Jr. Early Italian Paintings in the Yale University Art Gallery. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1970., 83, nos. 57–58. ↩︎

-

Fredericksen, Burton B., and Federico Zeri. Census of Pre-Nineteenth-Century Italian Paintings in North American Public Collections. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1972., 600; Fototeca Zeri, Federico Zeri Foundation, Bologna, inv. nos. 23463–64. ↩︎

-

Frinta, Mojmír S. Punched Decoration on Late Medieval Panel and Miniature Painting. Vol. 1, Catalogue Raisonné of All Punch Shapes. Prague: Maxdorf, 1998., 41, no. Aa15b. ↩︎

-

It is worth speculating whether the unusual choice to show Saint Lawrence with the attribute of a chalice might be related, in this instance, to Genoese devotion to the Eucharist and the sacro catino, the glass dish in the cathedral of Saint Lawrence that was identified with the Holy Chalice by Jacobus de Voragine, archbishop of Genoa from 1292 until his death in 1298. See Müller, Rebecca. “Il ‘Sacro Catino’: Percezione e memoria nella Genova medievale.” In Intorno al Sacro Volto: Genova, Bisanzio e il Mediterraneo (secoli XI–XIV), ed. Anna Rosa Calderoni Masetti, Colette Dufour Bozzo, and Gerhard Wolf, 93–104. Venice: Marsilio, 2007., 93–104. ↩︎