Icilio Federico Joni (1866–1946), Siena; Dan Fellows Platt (1873–1937), Englewood, N.J., 1909; Maitland Fuller Griggs (1872–1943), New York, 1926

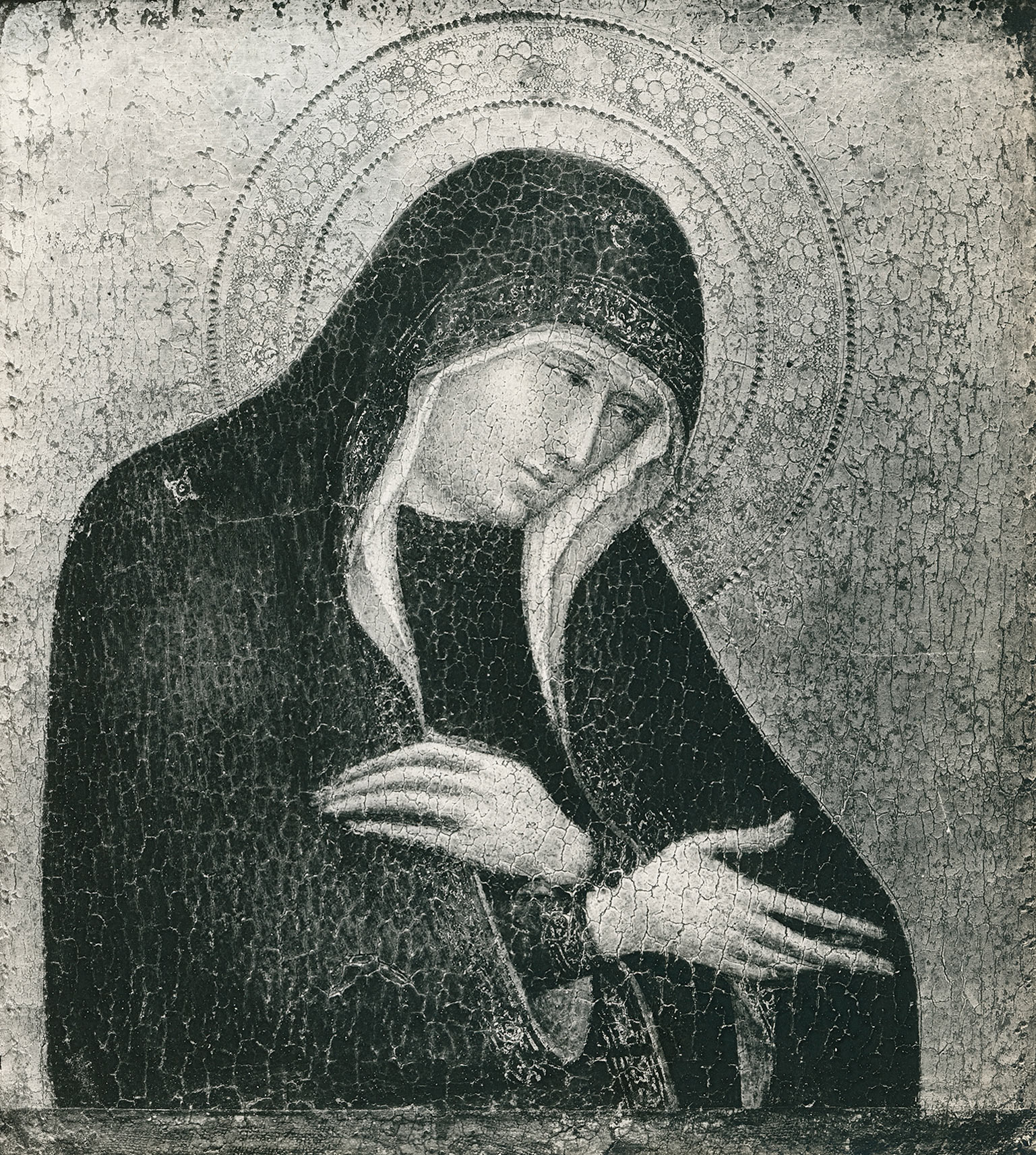

The panel, of a horizontal grain exhibiting a modest convex warp, measures 1.5 centimeters in depth and apparently has not been thinned except for slight beveling along all four sides of the reverse. The composition has been trimmed by a few millimeters at the left, top, and right edges, cropping the tips of an arcade of punch decoration. The lowest 2 centimeters of the picture field have been scraped down to gesso and linen across the full width of the panel. The paint surface has been almost entirely consumed by caustic solvent damage, the dry, leached effect exacerbated by a gray synthetic varnish applied by Andrew Petryn following a cleaning in 1958.

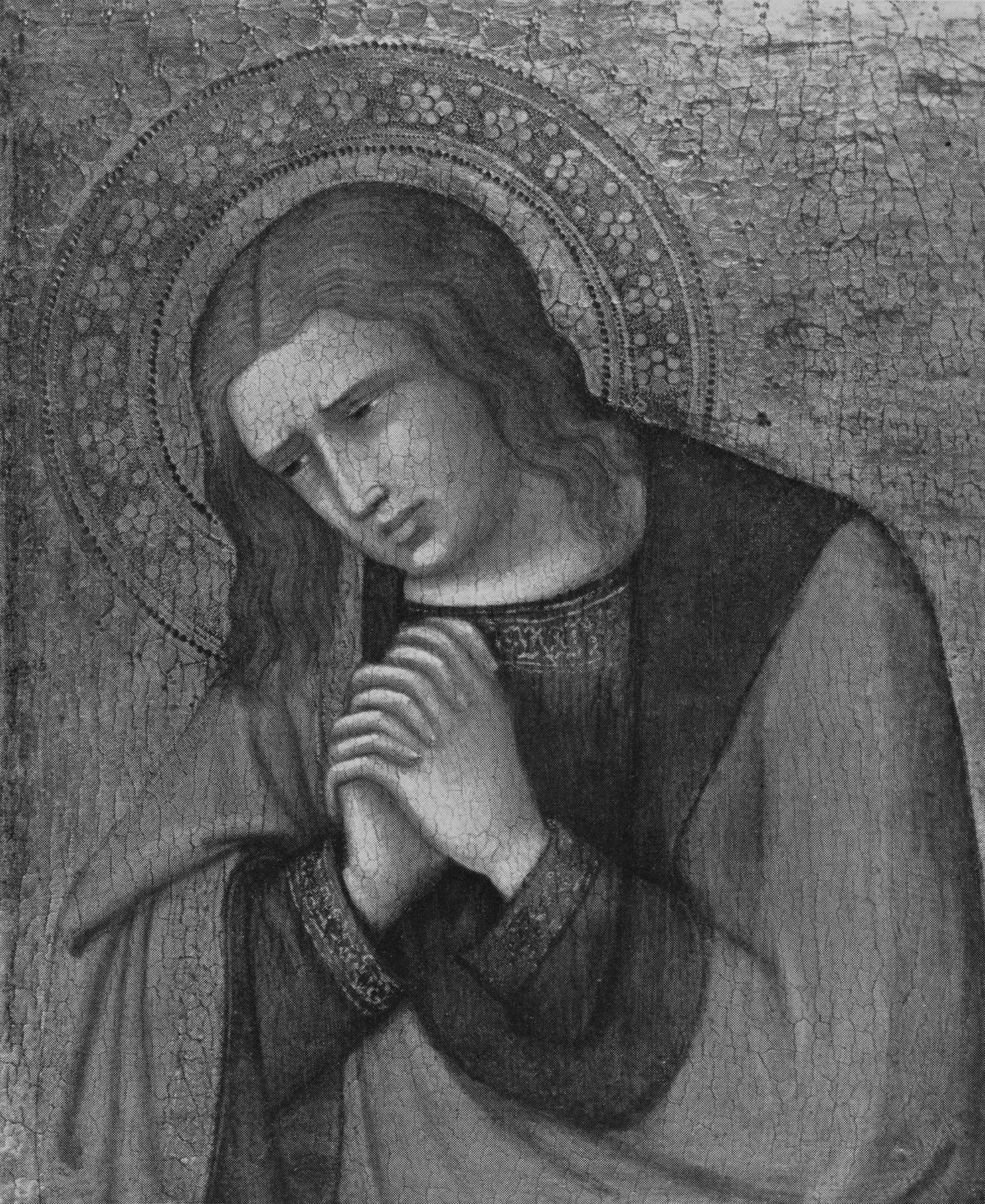

Acquired by Maitland Griggs in 1926 in a damaged and heavily repainted state, this painting of the Mourning Virgin was given only a generic attribution by Richard Offner to the Sienese school in the second quarter of the fourteenth century.1 Bernard Berenson was the first to advance a qualified attribution to Pietro Lorenzetti,2 a name that accompanied the painting into at least the mid-1970s.3 In his review of Charles Seymour, Jr.’s 1970 catalogue of the Yale collection, Everett Fahy pointed out the painting’s relation to a panel formerly in the Van Gelder collection at Uccle, Belgium, representing the mourning Saint John the Evangelist (fig. 1).4 The Van Gelder panel, which has clearly been cropped at the sides and bottom, is similar in size (30.5 × 25.4 cm) to the Yale panel and identical to it in the punched decoration of its gold ground. Fahy called both pictures simply Sienese, ca. 1340, and Carlo Volpe also refused to commit to an attribution to Pietro Lorenzetti or his workshop.5 The ex-Van Gelder Saint John, by then with the dealer Piero Corsini, was attributed by Miklós Boskovits to Barnaba da Modena but apparently without referencing the Yale Virgin alongside it. This attribution was first reported by Giuliana Algeri in 1989, again without mentioning the companion panel at Yale, and she also advanced a proposal to date the painting to the late 1370s.6 Both panels were finally published as Barnaba da Modena in Mojmír Frinta’s catalogue of punch-tool decoration of gold-ground panels.7

Both the attribution to Barnaba da Modena and the proposal to date these panels to the late 1370s are fully persuasive. Although the condition of both, especially of the Yale panel, makes any precise judgment impossible, the outlines of the figures and the tension of their postures are closely related to similar details in the altarpiece by Barnaba in San Bartolomeo del Fossato, Genoa. Algeri rehearsed the contradictory arguments for dating this altarpiece advanced by earlier scholarship and concluded, again persuasively, by accepting a date between December 1377 and September 1382. Given such a dating, it is unclear whether the Yale and Van Gelder panels might have been painted in Genoa or in Pisa, where Barnaba had relocated by June 1379. As it first appeared on the market in Siena in 1909, it might be presumed that this panel more likely had a Tuscan (i.e., Pisan) rather than Ligurian provenance, but in the absence of further documentary material, such circumstantial evidence is purely speculative.

One further unresolved argument in studies of the Yale and Van Gelder panels is whether they might have formed parts of an altarpiece predella, presumably flanking a lost image of Christ as the Man of Sorrows8 or terminals of a large painted crucifix.9 Again, definitive evidence is lacking, but it seems more likely that the panels were excised from a predella. The Yale panel retains what appears to be its original thickness, with original cross-grain gouges of a planing tool on the reverse, and this thickness, only 15 millimeters, would seem insufficient to the terminals of a large painted cross. Furthermore, such terminals in surviving fourteenth-century examples generally extend slightly above and below the width of the crossarm of the crucifix and are therefore composed of three boards: one wider central board continuing the plank of the crossarm and two others, considerably smaller, joined to it at the top and bottom for the vertical extensions and for any decorative framing elements that might also have been included. The Yale panel shows no evidence of any seams from such a construction. Finally, pre-“restoration” photographs of the Yale panel (fig. 2) show a painted strip running the width of the panel along its lower edge. In its present state, this strip has been reduced to exposed linen, but fragments of original green paint are preserved in this area, suggesting that it once portrayed either a decorative framing element or an illusionistic “shelf” or ledge behind which the Virgin appeared. The Van Gelder panel has been reduced in height, eliminating any trace of such a painted strip across its base. While not conclusive, the presence of such a painted device again seems more appropriate to a predella than to a painted crucifix.

Barnaba da Modena painted at least two Virgin and Child compositions of a domestic, devotional scale that include small painted predellas with Christ as the Man of Sorrows in their center, flanked by the Virgin and Saint John the Evangelist. One of these, now in the Alana Collection, Newark, Delaware, is dated 1380 by inscription. The other was formerly in a private collection in Genoa (current location unknown; also recorded in a contemporary copy in the Kress Collection at the Benton Museum of Art at Pomona College, Claremont, California), leading to the presumption that the type might have been Genoese in origin.10 Paintings of a similar format appeared in the first half of the century in Siena, particularly in the workshop of Lippo Memmi and Simone Martini, so it remains unclear whether it is possible to localize a market for paintings with this subject matter. The Man of Sorrows as a presence in altarpiece predellas is commonly encountered throughout Tuscany in the fourteenth century. In the Veneto, by contrast, that subject generally appears in altarpiece pinnacles rather than predellas. Insufficient evidence survives from fourteenth-century Liguria to be conclusive. —LK

Published References

Berenson, Bernard. Italian Pictures of the Renaissance: A List of the Principal Artists and Their Works with an Index of Places. Oxford: Clarendon, 1932., 293; Berenson, Bernard. Italian Pictures of the Renaissance, A List of the Principal Artists and Their Works with an Index of Places: Central Italian and North Italian Schools. 3 vols. London: Phaidon, 1968., 1:219; Seymour, Charles, Jr. Early Italian Paintings in the Yale University Art Gallery. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1970., 77, 79, 310, no. 52; Fredericksen, Burton B., and Federico Zeri. Census of Pre-Nineteenth-Century Italian Paintings in North American Public Collections. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1972., 600; Charles Seymour, Jr., in Seymour, Charles, Jr., et al. Italian Primitives: The Case History of a Collection and Its Conservation. Exh. cat. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1972., 8, no. 52; Preiser, Arno. Das Entstehen und die Entwicklung der Predella in der italienischen Malerei. Hildesheim, Germany: Georg Olms, 1973., 234, 382, 415, no. 227; Fahy, Everett. Review of Paintings from the Samuel H. Kress Collection: Italian Schools XII–XV Century, by Fern Rusk Shapley; Paintings from the Samuel H. Kress Collection: Italian Schools XV–XVI Century, by Fern Rusk Shapley; Early Italian Paintings in the Yale University Art Gallery, by Charles Seymour, Jr.; and Italian Primitives: The Case History of a Collection and Its Conservation, by Charles Seymour, Jr. Art Bulletin 56, no. 2 (June 1974): 283–85., 285; Volpe, Carlo. Pietro Lorenzetti. Milan: Electa, 1989., 205–6; Frinta, Mojmír S. Punched Decoration on Late Medieval Panel and Miniature Painting. Vol. 1, Catalogue Raisonné of All Punch Shapes. Prague: Maxdorf, 1998., 179, 219

Notes

-

Opinion, 1927, recorded in the Frick Art Reference Library, New York. ↩︎

-

Berenson, Bernard. Italian Pictures of the Renaissance: A List of the Principal Artists and Their Works with an Index of Places. Oxford: Clarendon, 1932., 293; and Berenson, Bernard. Italian Pictures of the Renaissance, A List of the Principal Artists and Their Works with an Index of Places: Central Italian and North Italian Schools. 3 vols. London: Phaidon, 1968., 1:219. ↩︎

-

Seymour, Charles, Jr. Early Italian Paintings in the Yale University Art Gallery. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1970., 77, 79, no. 52; Fredericksen, Burton B., and Federico Zeri. Census of Pre-Nineteenth-Century Italian Paintings in North American Public Collections. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1972., 600; Charles Seymour, Jr., in Seymour, Charles, Jr., et al. Italian Primitives: The Case History of a Collection and Its Conservation. Exh. cat. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1972., 8, no. 52; and Preiser, Arno. Das Entstehen und die Entwicklung der Predella in der italienischen Malerei. Hildesheim, Germany: Georg Olms, 1973., 234, 382, 415, no. 227. ↩︎

-

Fahy, Everett. Review of Paintings from the Samuel H. Kress Collection: Italian Schools XII–XV Century, by Fern Rusk Shapley; Paintings from the Samuel H. Kress Collection: Italian Schools XV–XVI Century, by Fern Rusk Shapley; Early Italian Paintings in the Yale University Art Gallery, by Charles Seymour, Jr.; and Italian Primitives: The Case History of a Collection and Its Conservation, by Charles Seymour, Jr. Art Bulletin 56, no. 2 (June 1974): 283–85., 285. The Van Gelder painting was sold at Christie’s, London, May 14, 1971, lot 14. ↩︎

-

Volpe, Carlo. Pietro Lorenzetti. Milan: Electa, 1989., 205–6. ↩︎

-

Algeri, Giuliana. “L’attività tarda di Barnaba da Modena: Una nuova ipotesi di ricostruzione.” Arte cristiana 77, no. 732 (May–June 1989): 189–210., 189–210. ↩︎

-

Frinta, Mojmír S. Punched Decoration on Late Medieval Panel and Miniature Painting. Vol. 1, Catalogue Raisonné of All Punch Shapes. Prague: Maxdorf, 1998., 179, 219. ↩︎

-

Seymour, Charles, Jr. Early Italian Paintings in the Yale University Art Gallery. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1970., 79, no. 52; and Preiser, Arno. Das Entstehen und die Entwicklung der Predella in der italienischen Malerei. Hildesheim, Germany: Georg Olms, 1973., 234, 382, 415, no. 227. ↩︎

-

Berenson, Bernard. Italian Pictures of the Renaissance: A List of the Principal Artists and Their Works with an Index of Places. Oxford: Clarendon, 1932., 293; Berenson, Bernard. Italian Pictures of the Renaissance, A List of the Principal Artists and Their Works with an Index of Places: Central Italian and North Italian Schools. 3 vols. London: Phaidon, 1968., 1:219; Fahy, Everett. Review of Paintings from the Samuel H. Kress Collection: Italian Schools XII–XV Century, by Fern Rusk Shapley; Paintings from the Samuel H. Kress Collection: Italian Schools XV–XVI Century, by Fern Rusk Shapley; Early Italian Paintings in the Yale University Art Gallery, by Charles Seymour, Jr.; and Italian Primitives: The Case History of a Collection and Its Conservation, by Charles Seymour, Jr. Art Bulletin 56, no. 2 (June 1974): 283–85., 285; and Algeri, Giuliana. “L’attività tarda di Barnaba da Modena: Una nuova ipotesi di ricostruzione.” Arte cristiana 77, no. 732 (May–June 1989): 189–210., 208–9n39. ↩︎

-

Di Fabio, Clario. “Barnaba da Modena a Genova: Le icone con finta predella; Note su una tipologia, tre autografi, una derivazione.” In Forme e storia: Scritti di arte medievale e moderna per Francesco Gandolfo, ed. Walter Angelelli and Francesca Pomarici, 433–44. Rome: Artemide, 2011., 433–44. ↩︎