Giovanni Gozzadini (1810–1887), Eremo di Ronzano, Bologna; by descent to Gozzadina Gozzadini (1845–1899); Alvise Francesco Orso Da Schio (1840–1920), 1905;1 Gozzadini sale, A. Rambaldi, Bologna, March 12–13, 1906, lot 50; E. and A. Silberman Galleries, New York, by 1936; Hannah D. Rabinowitz and Louis M. Rabinowitz (1887–1957), Sands Point, Long Island, N.Y., by 1945

The panel support, of a vertical wood grain, has been thinned to a depth of 7 millimeters, cradled, and waxed. It is much consumed by woodworm damage, especially along the bottom edge, and is interrupted by numerous splits, four of which extend the full height of the panel: at the left through the figure of the Crucified Christ and the Magdalen’s arms; at the right through the Virgin’s right shoulder, through Christ’s outstretched right hand, and through Christ’s left shoulder. These full splits have resulted in extensive paint loss, above all in the body of the Crucified Christ and in the Virgin’s blue robe in the Coronation scene. At the bottom, the second and fourth apostles from the left and the second apostle from the right are compromised by paint losses, and in the Crucifixion scene, a candle burn has left a large area of loss in Saint John the Evangelist’s thigh. The gold ground in the Crucifixion is heavily abraded, exposing bolus and gesso throughout, but it is well preserved in the predella. The paint surface, except for the described losses, is unusually well preserved, having suffered minimal abrasion other than unnecessarily harsh cleaning of some of the lighter-colored draperies when the panel was treated by Andrew Petryn at an unrecorded date after 1970. Fragmentary remnants of a barb are preserved along all four edges of the paint surface. The mark of a carpenter’s saw cutting a mitered corner for the original engaged frame is preserved at the upper-right margin of the panel.

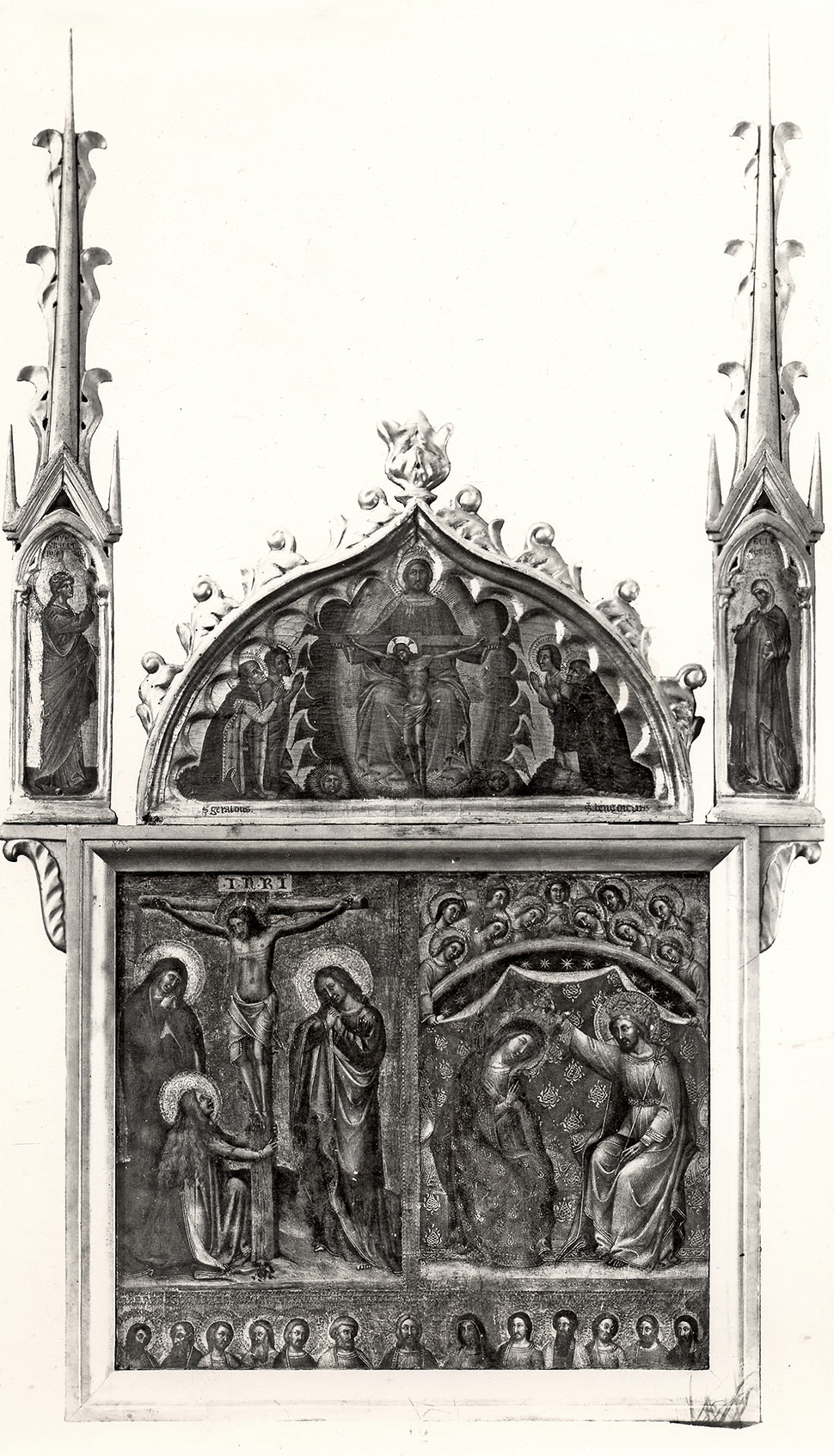

This small panel, most likely intended for private devotion, is divided into two equal sections separated by a strip of punched gold. On the left is the Crucified Christ between the Mourning Virgin and Saint John the Evangelist, with the penitent Magdalen at the foot of the Cross. The Virgin wears a blue mantle lined in yellow with red highlights over a (repainted) blue dress. Mary Magdalen is dressed in a light blue gown with gold trim and a brilliant red mantle with white lining. Saint John the Evangelist wears a purple cloak lined in light blue over a moss-colored tunic with yellow highlights and gold trim. The Coronation of the Virgin shows Christ as king, holding a scepter in His left hand while placing a gold crown over the head of His Mother with His right. The Virgin, in a purple dress and blue mantle with gold borders, bends her head to receive the crown while crossing her hands over her breast. Christ wears a light blue tunic, gathered at the waist by a gold belt, and a purple mantle lined with the same moss color of Saint John the Evangelist’s dress. The figures are seated on gold pillows on an invisible throne covered by a bright red, ermine-lined cloth of honor with a gold pomegranate pattern. In the background is a starry sky and the arched vault of the Heavens, beyond which eleven angels stand witness to the event; two of them, in lavender-colored gowns, reach over the arch to hold up the cloth of honor. Below the Crucifixion and Coronation, separated by another strip of punched gold, are bust-length images of the twelve apostles, with the figure of Christ in the middle.

The Yale panel is first recorded in the collection of the Bolognese nobleman Giovanni Gozzadini, who described it among the objects in his residence in Ronzano, an old hermitage in the hills outside Bologna that he acquired in 1848. Gozzadini, who attributed the picture to Simone dei Crocifissi, listed it after two other works by the artist also in his possession: a larger signed Coronation of the Virgin, now in a private collection in Turin, and two laterals of an unidentified altarpiece showing Saint Anthony Abbot and Saint Thaddeus, later in the Spinelli collection, Florence (present location unknown).2 Mentioned later was a fourth work by Simone, described by Gozzadini as “one of the most precious” that the artist had ever painted—a lunette with the Trinity between Saint Gerald of Aurillac, Saint John the Baptist, Saint Benedict, and an unidentified male saint, presently in the Paintings Gallery of the Academy of Fine Arts, Vienna.3 At the 1906 sale of the Gozzadini collection, the Yale panel and the Trinity, along with two pinnacles with the Annunciation by Paolo Veneziano now in the Wadsworth Atheneum, Hartford, Connecticut,4 were arbitrarily joined together to form a small altarpiece attributed to Simone and listed as a single lot (fig. 1).5 Subsequent authors referred to the complex, known only through the reproduction published in the Gozzadini sale catalogue, as a typical work of the artist. Raimond van Marle related it to the signed Christ and the Virgin Enthroned with Saints and Two Donors panel in the Pinacoteca Nazionale, Bologna (fig. 2), and based on the presence of a supposed portrait of Pope Urban V in the latter, he dated both works to Urban’s pontificate (1362–70).6 The correspondences between the Bologna picture and the Yale/Vienna complex were also noted by Wart Arslan, who identified them as products of a presumed “third follower” of Simone, active in the artist’s workshop in the 1360s.7

By the time Yale panel reappeared on the art market in 1936, it had been separated from the Vienna lunette and Hartford pinnacles.8 Since then, scholars have concurred in situating it among Simone’s autograph production. With the exception of Charles Seymour, Jr., who dated the panel around 1370,9 most authors have placed the Yale Crucifixion and Coronation in the 1380s, including it among the numerous small panels for private devotion produced by Simone’s busy workshop during this decade—a period when the artist’s professional success can also be measured by the various important roles he held in public office.10 The serial nature of this production, however, defined by a repetition of motifs and figural types, makes a relative dating difficult. The only fixed terminus post quem for the Yale panel is the signed and dated 1382 Coronation of the Virgin formerly in the church of Santa Maria Incoronata, in Bologna, and now in the Opera Pia Zoni (fig. 3). Including the Yale example, this image is one of at least ten versions of the subject painted by the artist according to the Venetian prototype, with Christ crowning with one hand and holding a scepter in the other—and, in the background, a starry sky and the arch of the Heavens with one or more rows of angels.11 In contrast to the tight execution of the Incoronata panel, the Yale painting is distinguished by the heavier outlines, deep shadows, and caricatured expressiveness—especially noticeable in the grimacing features of the mourning figures in the Crucifixion—that are generally associated with the last decades of the artist’s activity. Although these elements prompted Arslan to posit the intervention of an assistant, the harmonious color symmetry and lavish attention to decorative details in the haloes and punched borders of the Yale picture are consistent with the artist’s vision. As noted by the earliest critics, the closest work in terms of compositional format and style is the signed altarpiece with Christ and the Virgin Enthroned in Bologna (see fig. 2), which also shows multiple scenes spread over a unified picture field and retains its original engaged frame, whose simplicity of design may provide a clue to the missing molding in the Yale panel. The more aggressive chiaroscuro of the Bologna painting is possibly indicative of a marginally later date of execution, as suggested by past scholars, although the stripped state of the Yale picture surface should perhaps be taken into consideration before drawing any firm conclusions. Most recently, Gianluca del Monaco preferred to compare the Yale Crucifixion, and especially the figure Saint John the Evangelist, to a devotional triptych by Simone in the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford (fig. 4), and dated these two images between 1385 and 1390, placing the Bologna panel between 1390 and 1395.12

In his discussion of Simone’s oeuvre, del Monaco discerned a close stylistic proximity between the Yale Crucifixion and Coronation and the Vienna lunette with the Trinity, which he assigned to the same period.13 While highlighting the different states of preservation of the two panels, already evident at the time of the Gozzadini sale, del Monaco cautiously speculated whether they may, in fact, have originally belonged to the same complex, in an arrangement comparable to that attempted in the Gozzadini sale. Del Monaco cited as a precedent the multitiered structure of Tommaso da Modena’s small altarpiece in the Pinacoteca Nazionale, Bologna.14 Such a hypothesis seems unlikely, however, given the radically different framing elements of the Yale and Vienna panels. Additionally, the Trinity appears marked by a tighter, more polished approach and less pronounced mannerisms in the rendering of facial expressions that suggest an earlier chronology.15 These qualifications aside, the vertical grain of the Yale panel does leave open the possibility that it could have had another unidentified element above it. —PP

Published References

Gozzadini, Giovanni. Cronaca di Ronzano e memorie di Loderingo d’Andaló frate gaudente. Bologna: Società Tipografica Bolognese, 1851., 117n216; Rambaldi, A. Collection de tableaux et objects d’art qui appartenaient au comte senateur Jean Gozzadini. Sale cat. March 12–13, 1906., 17–18, lot 50, pl. 8; Baldani, Renato. La pittura a Bologna nel secolo XIV. Documenti e studi pubblicati per cura della Regia Deputazione di Storia Patria per la Romagna 3. Bologna: Azzoguida, 1909., 465, pl. 10; van Marle, Raimond. The Development of the Italian Schools of Painting. Vol. 4. The Hague: M. Nijhoff, 1924., 448; Arslan, Wart [Edoardo]. “Note su Simone di Filippo, pittore bolognese del trecento.” Il comune di Bologna 1 (January 1930): 15–20., 19; The Centennial Exposition: Catalogue of the Exhibition of Paintings, Sculptures, Graphic Arts. Exh. cat. Dallas: Dallas Museum of Fine Arts, 1936., 14, 18, no. 16; Venturi, Lionello. The Rabinowitz Collection. New York: Twin Editions, 1945., 9–10, pl. 5; Longhi, Roberto. Viatico per cinque secoli di pittura veneziana. Florence: Sansoni, 1946., reprinted in Longhi, Roberto. Ricerche sulla pittura veneta: 1946–1969. Edizione delle opere complete di Roberto Longhi 10. Florence: Sansoni, 1978., 41; “Recent Gifts and Purchases: February 22–December 31, 1959.” Yale University Art Gallery Bulletin 26, no. 1 (December 1960): 52–58., 53; Seymour, Charles, Jr. The Rabinowitz Collection of European Paintings. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1961., 54; Volpe, Carlo. “Il polittico di Paolo Veneziano.” In Il tempio di San Giacomo Maggiore in Bologna: Studi sulla storia e le opere d’arte, 87–91. Bologna: n.p., 1967., 88, fig. 24; Seymour, Charles, Jr. Early Italian Paintings in the Yale University Art Gallery. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1970., 102–3, no. 71; Fredericksen, Burton B., and Federico Zeri. Census of Pre-Nineteenth-Century Italian Paintings in North American Public Collections. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1972., 601; Jean K. Cadogan, in Cadogan, Jean K., ed. Wadsworth Atheneum Paintings. Vol. 2, Italy and Spain: Fourteenth through Nineteenth Centuries. Hartford, Conn.: Wadsworth Atheneum, 1991., 252; Andrea De Marchi, in Laclotte, Michel, et al. Autour de Lorenzo Veneziano: Fragments de polyptyques vénitiens du XIVe siècle. Exh. cat. Cinisello Balsamo, Milan: Silvana, 2005., 118, 121, fig. 109; Ada Labriola, in Boskovits, Miklós, ed. Italian Paintings from the 13th to the 15th Century. The Alana Collection 1. Florence: Polistampa, 2009., 191n12; del Monaco, Gianluca. Simone di Filippo detto “Dei Crocifissi”: Pittura e devozione nel secondo trecento bolognese. Padua: Il Poligrafo, 2018., 69, 200–202, 232, no. 69, pl. 65

Notes

-

With the death in 1899 of Gozzadina, Giovanni’s only child, the Gozzadini family line was extinguished. In 1905, after a protracted legal battle over the terms of Gozzadina’s will, the Gozzadini Palace in Bologna and the villa in Ronzano, together with its art collection, were awarded to her cousin, Alvise Francesco Orso. The latter organized the sale of the entire collection the following year. See Bollini, Maria Grazia. “Il fondo speciale Carte Gozzadini e Da Schio della Biblioteca Comunale dell’Archiginnasio.” L’Archiginnasio 114 (2019): 245–328., 245–328. ↩︎

-

Gozzadini, Giovanni. Cronaca di Ronzano e memorie di Loderingo d’Andaló frate gaudente. Bologna: Società Tipografica Bolognese, 1851., 117n216. ↩︎

-

Inv. no. A 31. See Gozzadini, Giovanni. Cronaca di Ronzano e memorie di Loderingo d’Andaló frate gaudente. Bologna: Società Tipografica Bolognese, 1851., 117–18n216. ↩︎

-

Inv. nos. 41.156, 41.157. ↩︎

-

Rambaldi, A. Collection de tableaux et objects d’art qui appartenaient au comte senateur Jean Gozzadini. Sale cat. March 12–13, 1906.. In the same sale (lot 85), Simone’s other two panels with Saints Anthony Abbot and Thaddeus had also been arbitrarily joined to two cusps with the Annunciation. See del Monaco, Gianluca. Simone di Filippo detto “Dei Crocifissi”: Pittura e devozione nel secondo trecento bolognese. Padua: Il Poligrafo, 2018., 179–80, nos. 50a–b. ↩︎

-

van Marle, Raimond. The Development of the Italian Schools of Painting. Vol. 4. The Hague: M. Nijhoff, 1924., 448. ↩︎

-

Arslan, Wart [Edoardo]. “Note su Simone di Filippo, pittore bolognese del trecento.” Il comune di Bologna 1 (January 1930): 15–20., 19. ↩︎

-

The Centennial Exposition: Catalogue of the Exhibition of Paintings, Sculptures, Graphic Arts. Exh. cat. Dallas: Dallas Museum of Fine Arts, 1936., 14, 18, no. 16, where it was listed as property of E. and A. Silberman Galleries, New York. For the provenance history of the Hartford pinnacles, recognized as works of Paolo Veneziano by Longhi (in Longhi, Roberto. Viatico per cinque secoli di pittura veneziana. Florence: Sansoni, 1946., reprinted in Longhi, Roberto. Ricerche sulla pittura veneta: 1946–1969. Edizione delle opere complete di Roberto Longhi 10. Florence: Sansoni, 1978., 41); see Jean Cadogan, in Cadogan, Jean K., ed. Wadsworth Atheneum Paintings. Vol. 2, Italy and Spain: Fourteenth through Nineteenth Centuries. Hartford, Conn.: Wadsworth Atheneum, 1991., 252. ↩︎

-

Seymour, Charles, Jr. Early Italian Paintings in the Yale University Art Gallery. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1970., 102–3, no. 71. ↩︎

-

del Monaco, Gianluca. Simone di Filippo detto “Dei Crocifissi”: Pittura e devozione nel secondo trecento bolognese. Padua: Il Poligrafo, 2018., 80–81. ↩︎

-

For a discussion of the prototype and different versions by Simone, see Andrea De Marchi, in Laclotte, Michel, et al. Autour de Lorenzo Veneziano: Fragments de polyptyques vénitiens du XIVe siècle. Exh. cat. Cinisello Balsamo, Milan: Silvana, 2005., 118–21; and Ada Labriola, in Boskovits, Miklós, ed. Italian Paintings from the 13th to the 15th Century. The Alana Collection 1. Florence: Polistampa, 2009., 190–91. ↩︎

-

del Monaco, Gianluca. Simone di Filippo detto “Dei Crocifissi”: Pittura e devozione nel secondo trecento bolognese. Padua: Il Poligrafo, 2018., 137–38, no. 27; 200–201, no. 69; and 202, no. 70. ↩︎

-

del Monaco, Gianluca. Simone di Filippo detto “Dei Crocifissi”: Pittura e devozione nel secondo trecento bolognese. Padua: Il Poligrafo, 2018., 231–32, no. 93. ↩︎

-

Inv. no. 289. ↩︎

-

The Vienna panel is unusual in that it includes a rare, if not unique, image in Italian painting of Saint Gerald of Aurillac, identified by the inscription “s.[anctus] geraldus” in red ink on the frame below him. Especially venerated in France, Gerald was born around the middle of the ninth century C.E. in the Auvergne region of the French Alps. According to the Vita Geraldi by Odo of Cluny, he was a nobleman and warrior who became known for his piety, chastity, and pacifism. One of the few medieval lay saints, he never took holy orders but left all of his land and wealth for the foundation of a Benedictine monastery at the site of what would become the modern city of Aurillac. See Kuefler, Mathew. The Making and Unmaking of a Saint: Hagiography and Memory in the Cult of Gerald of Aurillac. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2014.. In the Vienna lunette, he is depicted as a knight in golden armor with a red ermine-lined cloak, a symbol of nobility. Kneeling in adoration opposite him is Saint Benedict, also identified by an inscription. Like Simone’s 1368 Pietà for Johannes of Elthinl, commissioned for a foreign resident—possibly a German scholar or student at the famous University of Bologna—the Trinity may originally have decorated a small tabernacle or funerary monument for a French patron in the city, perhaps a prelate affiliated with the monastery at Aurillac. ↩︎