James Jackson Jarves (1818–1888), Florence, by 1859

The triptych is composed of three soft wood (fir or spruce) panels of a vertical grain, none of them thinned or cradled. The center panel is 1.7 centimeters thick. Its engaged frame moldings, 6 millimeters thick, are affixed with large, regularly spaced nails, four on each of the left, bottom, and right sides, and three in the two moldings forming the gabled top. The wings are each 1.5 centimeters thick. The hinges connecting the left wing and center panel are original, while the pair driven into the right wing are later replacements. A triangular insert of new wood on the reverse of the right wing, measuring 16 by 5 centimeters, replaces damage along its inner edge, and putty fills reinforce losses around both hinge loops. The left wing has putty fills along the center of its bottom edge and the top of its outer edge. The center panel is repaired with putty fills along the bottom and both side edges. A split in the left wing 6.5 centimeters from its outer edge extends approximately 16 centimeters down from the top edge.

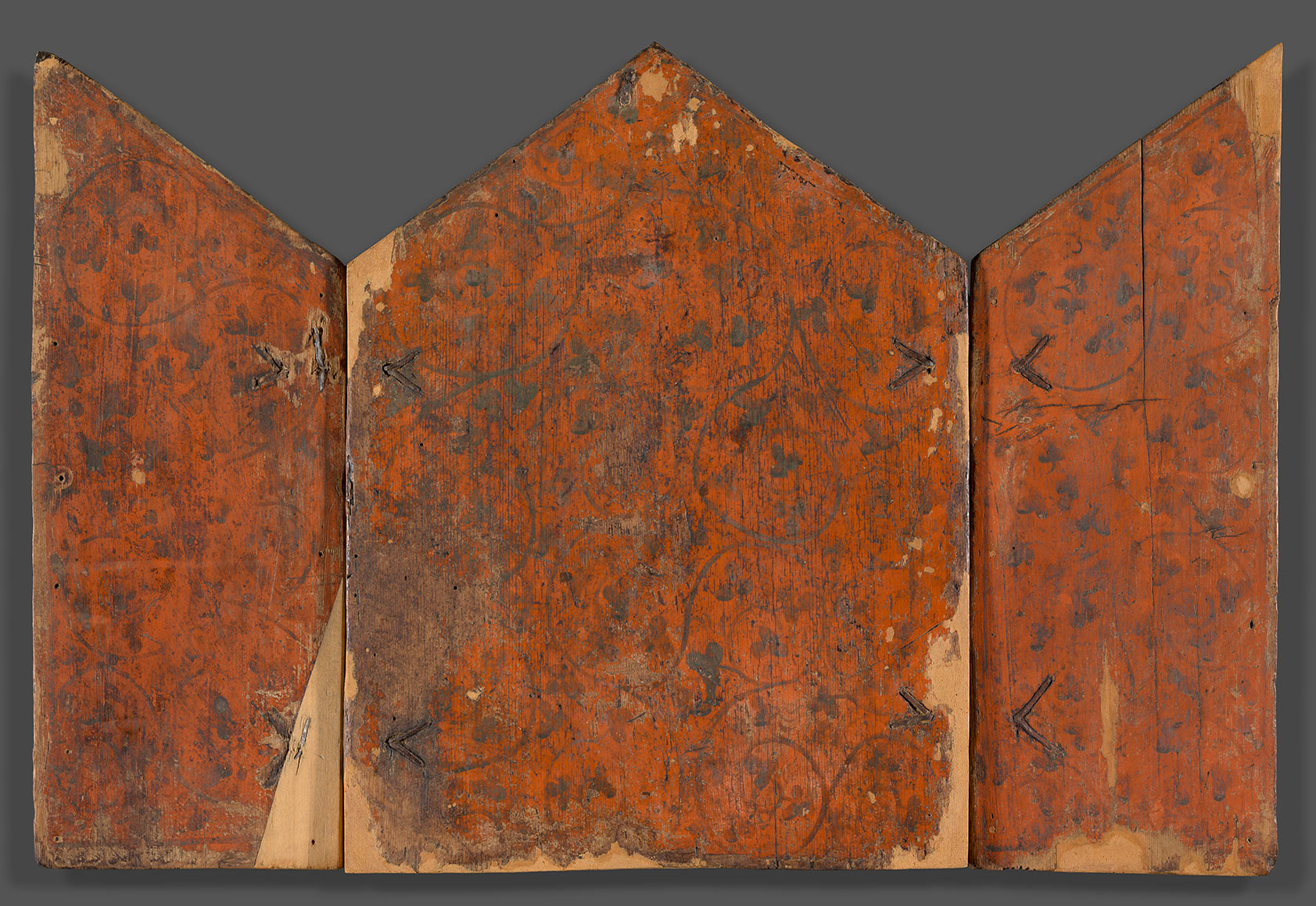

A harsh cleaning in 1965–68 exposed and exacerbated damage from earlier interventions. The silver ground and paint surfaces throughout the triptych are much consumed by solvent damage and overall abrasion; the scenes retain their general legibility but virtually nothing of their painterly qualities. The decoration on the backs of the center panel and wings (fig. 1), although worn, has not been deliberately disfigured by restoration. It is applied directly to the panel surface, with no gesso preparatory layer beneath.

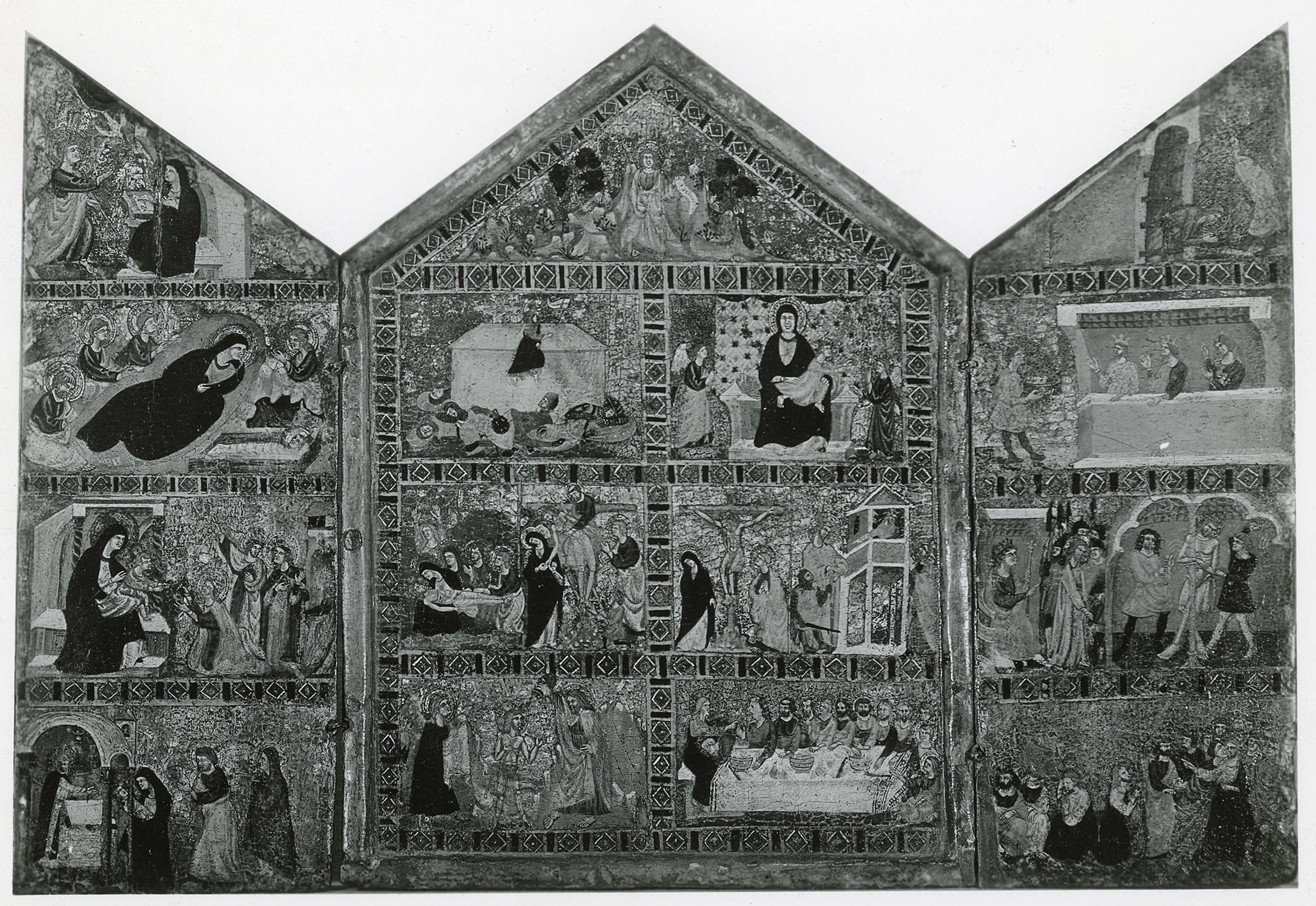

This small portable triptych, remarkable for the number of narrative scenes included in the main compartment as well as in the wings, illustrates sixteen episodes from the life of Christ and three from the life of Saint John the Baptist. The Christological cycle begins at the top of the left wing with the Annunciation, below which is the Nativity, followed by the Adoration of the Magi and the Presentation in the Temple. In the central panel, six rectangular fields contain seven other episodes, beginning with the Baptism of Christ (lower left), followed by the Last Supper (lower right), the Ecce Homo and Crucifixion (middle right), the Deposition and Lamentation (middle left), and the Resurrection (upper left). In the field at the upper right is an image of the Enthroned Virgin and Child with two angels. The Christ Child is shown standing on the Virgin’s lap, reaching for a bird held in a snare by the angel on the right—a biblical allusion to the trapped human soul and Christ’s role as Redeemer. In the gable above these scenes is Saint John the Baptist in the Wilderness. At the bottom of the right wing are two quadrants with four more scenes from Christ’s Passion: the Agony in the Garden, the Kiss of Judas, Christ before Pilate, and the Flagellation. Two episodes from the life of Saint John the Baptist fill a quadrant and the gable above these: his Beheading outside the Prison Gates and the Feast of Herod. Dividing the main scenes is a wide decorative band with a red, white, and black geometric pattern composed of large diamonds alternating with vertical or horizontal stripes. The back of the main compartment and the outside of both wings are decorated with a black vine-and-clover motif painted against a red background (see fig. 1).

The proper evaluation of this triptych has undoubtedly been compromised by its poor state of preservation and the losses suffered in subsequent harsh cleanings, both before and after it entered the Yale collection. Already described in 1916 by Osvald Sirén as having “gone through a rather coarse treatment at a remote period,”1 the triptych underwent further restorations in the late 1960s, during which—judging from a comparison with old photographs (fig. 2)—the painted surface was completely abraded in large areas and the layers of modeling removed from the heads and bodies of most of the figures. While conceding that the picture may have lost some of its “original qualities,” Sirén nevertheless pointed to its “crude technique” and considered it a “weak imitation after the early Giottesque painters in the Romagna,” drawing analogies between some of the better-preserved figures in the triptych and Giuliano da Rimini’s production in the first decade of the fourteenth century. Sirén’s attribution to the Romagnole school was accepted by Raimond van Marle and Richard Offner.2 The latter, who proposed a considerably later date for the work, around 1350, confessed that he had “never seen anything quite like it” but conceded that the figure of the Virgin and the long-skirted Christ Child, the wide throne, and the painted partitions dividing the episodes “all commit one to Romagnole territory or to its artistic dependencies.” Edward Garrison subsequently listed the triptych as “North Umbrian or Marchigian under North Umbrian influence,” with a date between 1320 and 1330.3 A date around 1330 was also proposed by Charles Seymour, Jr., who catalogued the image as “School of Rimini” but pointed to Marchigian as well as Romagnole influences.4 Following Sirén, Seymour highlighted the compositional relationship of this work to the gabled panel with scenes from the lives of Christ and Saint Dominic in the Robert Lehman Collection at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York—a work formerly associated with the Romagna or the Marche but now unanimously recognized as by the Florentine Master of the Dominican Effigies.5 Barring Andrea De Marchi’s tentative association of the Yale triptych with the Florentine Master of Vicchio a Rimaggio,6 subsequent authors have concurred with earlier opinions identifying it as a product of the Romagnole or Riminese school in the early fourteenth century.

Despite efforts to relate the Yale triptych to Umbrian, Marchigian, and, most puzzlingly, Florentine painting, most of its compositional and stylistic elements, as first recognized by Sirén and Offner, point unequivocally to the Riminese school. As noted by Offner, the painted divisions with a black-and-white geometric design against a red background, as well as the uneven distribution of episodes, hark back to works such as Giovanni da Rimini’s diptych with scenes from the life of Christ, the Virgin, and other saints, presently divided between Rome and London.7 The nearest point of reference for the triptych’s figural style and for certain of its compositional elements, however, lies less in the work of the first generation of Riminese painters than in that of Pietro da Rimini. In contrast to the more staid Giottesque vocabulary of Giovanni or Giuliano da Rimini, the triptych reflects a closer adherence to the more expressive, incipiently Gothic idiom of Pietro’s production around the middle of the third decade of the fourteenth century, as evidenced in the fresco cycles for the convent of the Eremitani in Padua and the convent of Santa Chiara in Ravenna (fig. 3).8 Both of these works are echoed in the lively figural types with impossibly long necks, pinched features, and pointed chins that inhabit the Yale triptych—more clearly recognizable in premodern restoration photographs (see fig. 2)—as well as in the dynamic poses of the Christ Child in the central panel and left wing. The standing Child on the enthroned Virgin’s lap, lunging forward with extended arms, is compositionally indebted to the Santa Chiara Adoration but also brings to mind the larger striding figures that characterize both fresco cycles, the violent motion of their bodies reflected in the artificial sweep of the thick folds of drapery.

The iconographic and formal relationships between the Yale triptych and the frescoes in Padua and Ravenna suggest an artist with an intimate familiarity with Pietro’s workshop, working in the Romagnole region along the Adriatic coast. It is worth noting that the decoration of the exterior of the triptych closely recalls the naturalistic pattern against a red background on the reverse of the two small panels from the church of Mezzaratta in Bologna, now in Perugia and Zürich.9 Those images, generally attributed to the so-called Master of Verucchio—a close follower of Pietro whose identity is still open to debate—were discussed by Daniele Benati in terms of their strong dependence on the frescoes of Santa Chiara in Ravenna.10 The relevance of the production of the Master of Verucchio is also reflected in certain eccentricities of the Yale triptych, such as the inconsistent proportions of the figures and architectural elements, which parallel those in the panels from the Dossal of the Blessed Clare executed for the monastery of Santa Maria degli Angeli in Rimini, presently divided between Coral Gables, Florida (fig. 4), and London.11 The dossal, which once constituted the namepiece of the group now gathered under the name of the Master of Verucchio, has been persuasively dated after the Blessed Clare’s death in 1326 and before 1330.12 A comparable dating can be applied to the Yale triptych, which, although executed by a less accomplished hand, reflects a similar general dependency on Pietro’s vocabulary during the same period.

The presence of scenes from the life of Saint John the Baptist and the preeminence accorded the saint in the gable of the main compartment suggest that the Yale triptych may have been commissioned for a confraternity or oratory dedicated to the saint. Confraternities devoted to Saint John the Baptist or to San Giovanni Decollato, the patron saint of condemned prisoners, were often involved with the care and spiritual assistance of those awaiting execution.13 The possibility that the Yale triptych may have been commissioned for such an organization is underscored by the message of penitence and redemption reflected in the combination of the Baptist scenes with a complete Christological cycle and by the focus, in the central panel, on events from the Passion instead of the more typical image of the Virgin and Child. —PP

Published References

Jarves, James Jackson. Descriptive Catalogue of “Old Masters” Collected by James J. Jarves to Illustrate the History of Painting from A.D. 1200 to the Best Periods of Italian Art. Cambridge, Mass.: H. O. Houghton, 1860., 42, no. 10; Sturgis, Russell, Jr. Manual of the Jarves Collection of Early Italian Pictures. New Haven: Yale College, 1868., 19, no. 4; W. F. Brown, Boston. Catalogue of the Jarves Collection of Early Italian Pictures. Sale cat. November 9, 1871., 11, no. 4; Rankin, William. “Some Early Italian Pictures in the Jarves Collection of the Yale School of Fine Arts at New Haven.” American Journal of Archaeology 10, no. 2 (April–June 1895): 137–51., 138; Rankin, William. Notes on the Collections of Old Masters at Yale University, the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, the Fogg Museum of Harvard University. Wellesley, Mass.: Department of Art, Wellesley College, 1905., 7, no. 4; Sirén, Osvald. A Descriptive Catalogue of the Pictures in the Jarves Collection Belonging to Yale University. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1916., 29–30, no. 9; van Marle, Raimond. The Development of the Italian Schools of Painting. Vol. 4. The Hague: M. Nijhoff, 1924., 298, fig. 151; Offner, Richard. Italian Primitives at Yale University: Comments and Revisions. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1927., 41–42, figs. 34–34b; Garrison, Edward B. Italian Romanesque Panel Painting: An Illustrated Index. Florence: Leo S. Olschki, 1949., 131, no. 345; Seymour, Charles, Jr. Early Italian Paintings in the Yale University Art Gallery. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1970., 106–7, no. 74; Fredericksen, Burton B., and Federico Zeri. Census of Pre-Nineteenth-Century Italian Paintings in North American Public Collections. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1972., 236–37, 599; De Marchi, Andrea. “Il ‘Maestro del 1310’ e la fronda anti-giottesca: Intorno ad un ‘Crocifisso’ murale.” Prospettiva 46 (1986): 50–56., 55n10; Boskovits, Miklós. Frühe italienische Malerei: Gemäldegalerie Berlin, Katalog der Gemälde. Berlin: Mann, 1988., 137; Freuler, Gaudenz. “Manifestatori delle cose miracolose”: Arte italiana del ’300 e ’400 da collezioni in Svizzera e nel Liechtenstein. Exh. cat. Lugano-Castagnola, Switzerland: Fondazione Thyssen-Bornemisza, 1991., 124, fig. 2

Notes

-

Sirén, Osvald. A Descriptive Catalogue of the Pictures in the Jarves Collection Belonging to Yale University. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1916., 29–30, no. 9. ↩︎

-

van Marle, Raimond. The Development of the Italian Schools of Painting. Vol. 4. The Hague: M. Nijhoff, 1924., 298, fig. 151; and Offner, Richard. Italian Primitives at Yale University: Comments and Revisions. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1927., 41–42. ↩︎

-

Garrison, Edward B. Italian Romanesque Panel Painting: An Illustrated Index. Florence: Leo S. Olschki, 1949., 131, no. 345. ↩︎

-

Seymour, Charles, Jr. Early Italian Paintings in the Yale University Art Gallery. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1970., 106–7, no. 74. ↩︎

-

Inv. no. 1975.1.99, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/459041. ↩︎

-

De Marchi, Andrea. “Il ‘Maestro del 1310’ e la fronda anti-giottesca: Intorno ad un ‘Crocifisso’ murale.” Prospettiva 46 (1986): 50–56., 55n10. ↩︎

-

Galleria Nazionale di Arte Antica, Palazzo Barberini, Rome, inv. no. 1441; and National Gallery, London, inv. no. NG6656, https://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/paintings/giovanni-da-rimini-scenes-from-the-lives-of-the-virgin-and-other-saints. ↩︎

-

The execution of the Paduan cycle is traditionally placed around 1324, the date recorded on the lost polyptych by Giuliano and Pietro da Rimini for the same church. The dating of the Santa Chiara frescoes has oscillated from as early as around 1320 (see Pier Giorgio Pasini, in Emiliani, Andrea, Giovanni Montanari, and Pier Giorgio Pasini, eds. Gli affreschi trecenteschi da Santa Chiara in Ravenna: Il grande ciclo di Pietro da Rimini restaurato. Ravenna: Longo, 1995., 45–67) to the 1330s. A date not far removed from the Paduan cycle, as suggested by Massimo Medica, seems most likely; see Medica, Massimo. “Pietro da Rimini e la Ravenna dei da Polenta.” In Il trecento riminese: Maestri e botteghe tra Romagna e Marche. Ed. Daniele Benati. Exh. cat. Milan: Electa, 1995., 102–5. ↩︎

-

Galleria Nazionale dell’Umbria, Perugia, inv. no. 68; and Kunsthaus, Zürich. For a color illustration of the reverse of the Zürich panel, see Pasini, Pier Giorgio. La pittura riminese del Trecento. Milan: Cassa di Risparmio di Rimini, 1990., 152. ↩︎

-

See Daniele Benati, in Bon Valvassina, Caterina, and Vittoria Garibaldi, eds. Dipinti, sculture e ceramiche della Galleria Nazionale dell’Umbria: Studi e restauri. Florence: Arnaud, 1994., 158–60. Miklós Boskovits’s identification of the Master of Verucchio with Francesco da Rimini (in Boskovits, Miklós. “Da Giovanni a Pietro da Rimini.” Notizie da Palazzo Albani 17 (1988): 35–50., 40; and Boskovits, Miklós. “Per la storia della pittura tra la Romagna e le Marche ai primi del ’300—II.” Arte cristiana 81, no. 756 (May–June 1993): 163–82., 163–67) is questioned by Benati. See also Benati, Daniele. “Disegno del trecento riminese.” In Il trecento riminese: Maestri e botteghe tra Romagna e Marche, 29–57. Exh. cat. Milan: Electa, 1995., 52–54; and, more recently, Benati, Daniele. “Giovanni Baronzio nella pittura riminese del trecento.” In Giovanni Baronzio e la pittura a Rimini nel trecento, ed. Daniele Ferrara, 19–35. Exh. cat. Cinisello Balsamo, Milan: Silvana, 2008., 26, 35n32. ↩︎

-

National Gallery, London, inv. no. 6503, https://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/paintings/francesco-da-rimini-the-vision-of-the-blessed-clare-of-rimini. ↩︎

-

Alessandro Marchi, in Benati, Daniele, ed. Il trecento riminese: Maestri e botteghe tra Romagna e Marche. Exh. cat. Milan: Electa, 1995., 226–29, nos. 33–34. ↩︎

-

On these confraternities, see, most recently, Terpstra, Nicholas. “Confraternities and Capital Punishment: Charity, Culture, and Civic Religion in the Communal and Confessional Age.” In A Companion to Medieval and Early Modern Confraternities, ed. Konrad Eisenbichler, 212–31. Leiden, Netherlands: Brill, 2019., 212–31 (with previous bibliography). ↩︎