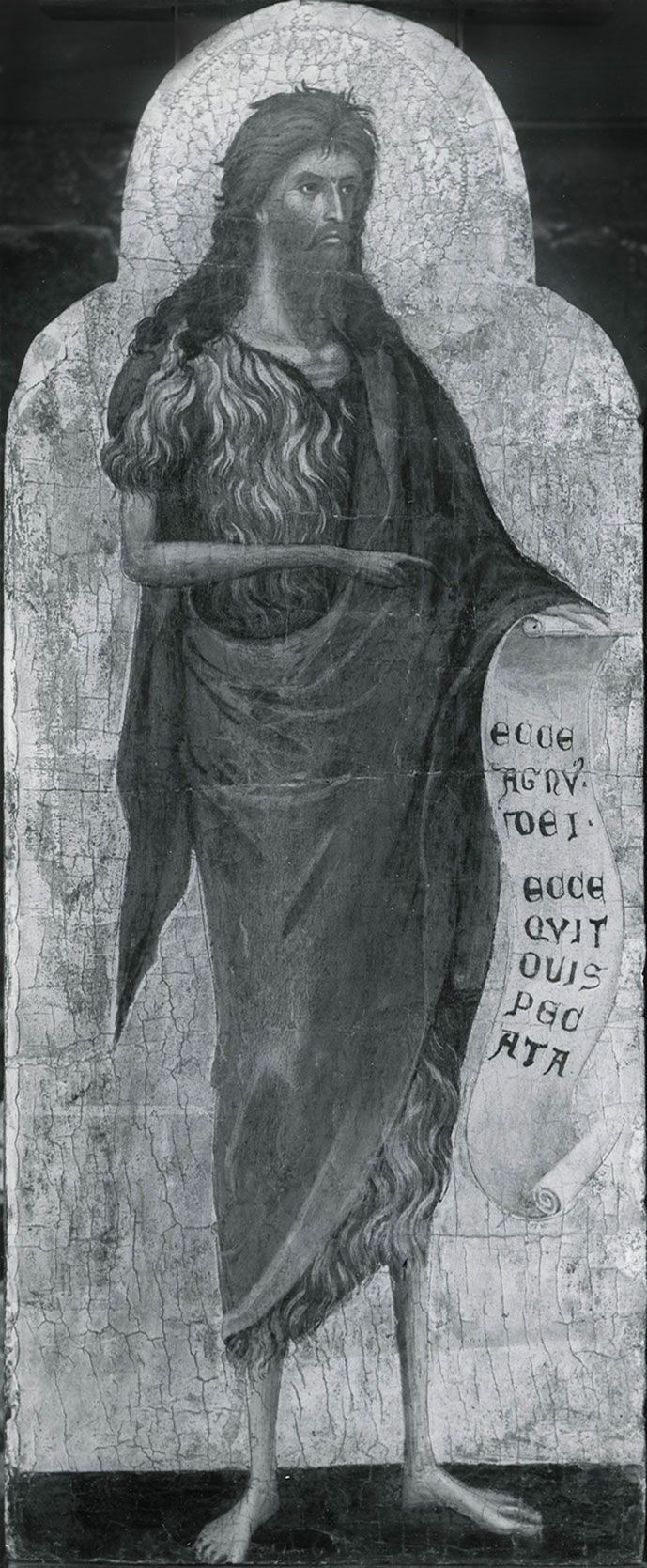

to the right of the saint, in red paint, remains of name; on the scroll, ECCE / AGNU[S] / DEI. / ECCE / QUI T / OLIS / PEC / ATA

Museo Guidi, Faenza(?);1 E. and A. Silberman Galleries, New York and Vienna, before 1938; Hannah D. and Louis M. Rabinowitz (1887–1957), Sands Point, Long Island, N.Y., by 1945

Both panels, of a horizontal wood grain, had been thinned to a depth of 3 millimeters, waxed, and cradled; the cradles and wax coating were removed in 2000 by Gianni Marussich. Splits in both panels were reinforced from behind with wedge inserts, but neither panel was deemed sufficiently sound to maintain its own structural integrity, so both were adhered to rigid birch plywood supports that have accentuated the “washboarding” effect of their surfaces. Saint Mary Magdalen has seven prominent horizontal splits, and Saint John the Baptist has fourteen. In the panel of the Baptist, a polished gesso border is visible at the left edge, separated from the painted surface by a scalloped incised line marking the placement of colonette and capital moldings. A fragmentary incision on the right side denotes the placement of the corresponding capital on that side, but the panel has been cropped inside of any incisions for a colonette beneath it. Conversely, a fragmentary border of the arch rising above the capital is visible at the right but not at the left. In the panel of the Magdalen, polished gesso and the inscribed profiles of the framing colonette, capital, and arch are visible at the right, while the left edge preserves traces of the inscribed profile of the capital and the lower part of the colonette. Both panels have been cropped at the top and bottom.

The gilding and paint surfaces of both panels have been extensively abraded. Losses in the gold ground of the Baptist panel, especially to either side of the figure’s torso, have been reinforced or toned to a worn gesso color and regilded along the right edge of the composition. The figure of the Baptist is largely free of retouching except for discreet inpainting along the splits and most prominent craquelure. A large damage at the top of the scroll has been compensated, as have scattered losses throughout the lower section of the scroll. The green base on which the Baptist stands has been reinforced. This panel was restored by Anne O’Connor in 2000, who applied a matte varnish and light retouching that both read well today. The panel of the Magdalen has been similarly reinforced over losses in the gold ground. Retouching of losses along the splits and scattered through the figure’s blue dress are more extensive than in the Baptist panel. The green base has also been heavily reconstructed, using a poorly matched tratteggio technique that slightly falsifies the profile of the lowest folds in the Magdalen’s dress. This panel was restored by Patricia Garland in 2000, who applied a glossy varnish that has pooled in the splits and open craquelure, exaggerating the flattening effect of the exposed abrasions of the surface.

The two saints, originally parts of the same complex, were first discussed by Evelyn Sandberg-Vavalà in 1939, when they were still in the New York gallery of Abris Silberman.2 Sandberg-Vavalà inserted the works in the production of Paolo Veneziano and his workshop, remarking on their “unusually expressive character” and comparing them to the “sterner, less ornate mood” of four panels with standing saints in the Harvard Art Museums, Cambridge, Massachusetts.3 While accepting the Yale pictures’ relationship to the work of Paolo Veneziano, subsequent authors have remained divided over their chronology and the extent of the artist’s direct participation in their execution. In the catalogue of the Rabinowitz Collection at Yale, Charles Seymour, Jr., accepted the attribution to Paolo and proposed a date in the 1330s, emphasizing the combination of Byzantine qualities, particularly evident in the “immobility” of the poses and “sobriety of expression,” with incipient Gothic elements, such as the “super-elongation of the forms and swing of the draperies.”4 Rodolfo Pallucchini, who reiterated Paolo’s authorship, remarked on the still-archaizing quality of the Magdalen and situated the panels’ execution in proximity to the polyptych in the Shalva Amiranashvili Museum of Fine Arts, Tbilisi, Georgia, between “the end of the fourth decade and beginning of the fifth decade” of the fourteenth century.5 Michelangelo Muraro concurred with Pallucchini in the dating of the Tbilisi polyptych around 1340 but distanced that work from the Yale Saint Mary Magdalen and Saint John the Baptist, which he regarded as a later workshop product from “around the middle of the century.”6 In his 1970 Yale catalogue, Seymour repeated the opinions he had expressed in the Rabinowitz Collection volume and dated the panels more precisely around 1335.7 In the exhibition curated by Seymour a few years later, however, Gloria Kury Keach was cautious about assigning the panels to Paolo’s own hand, writing that they were “good examples of the artist’s style, though conceivably executed by the bottega.”8 Paolo’s authorship was not questioned by Federico Zeri and Elizabeth Gardner, who nevertheless associated the panels with the last phase of the artist’s career, proposing that they may have been laterals from the same polyptych as the Virgin and Child Enthroned in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York9—a work generally placed around 1350 or later. This reconstruction was accepted by Alessandro Marchi, although he referred the altarpiece to Paolo’s workshop.10 In the most recent monograph devoted to the artist, Filippo Pedrocco listed the Yale Magdalen and John the Baptist under a separate category labeled “Paolo Veneziano and Workshop,” specifying that it referred to those works executed exclusively by collaborators based on the master’s models.11

Hitherto unacknowledged in discussions of the Yale Magdalen and John the Baptist are the qualitative differences that separate the two panels. The contrasts between them is especially evident in photographs taken before the 1959 cleaning by Andrew Petryn (figs. 1–2), which contributed to a flattening of the painted surface and elimination of the sensitively applied highlights that noticeably distinguished the handling of the Baptist. Compared to the almost generic, formulaic technique used in the figure of the Magdalen, the Baptist stands out for the meticulous attention to the articulation of the individual facial features and hands, as well as a concern with chiaroscuro effects that clearly emphasize the underlying bone structure and the individual folds of drapery. These elements denote a markedly more sophisticated approach that suggests Paolo’s direct involvement in the execution of this figure, and the probable intervention of assistants in the Magdalen.

Regardless of a debatable claim of a possible common provenance, Zeri and Gardner’s association of the Yale Saints with the Metropolitan Museum Virgin is unconvincing on stylistic grounds.12 Whereas the latter picture partakes of the fully developed Gothicism of the signed and dated 1347 Carpineta Madonna13—from which it derives the pose of the standing Christ Child—the Yale panels are indebted, in both palette and mood, to a pronouncedly more archaic, byzantinizing phase in the artist’s career. A considerable lapse in time must undoubtedly separate the rigidly severe figure of the Baptist not only from the impossibly elongated aristocratic saint of the 1349 Chioggia polyptych but also from the elegant, livelier figure in the Worcester Art Museum, Massachusetts, associated with a dismembered portable triptych convincingly dated to the early 1340s.14 Even more distant from the Yale saint is the image in the Tbilisi polyptych cited as a comparison by Muraro, which, though based on the same iconographic type, employs an altogether different facial physiognomy and is more insubstantial and schematic in execution.15

Among Paolo’s signed and dated works, the nearest point of reference for the Yale Magdalen and John the Baptist are the hieratic lateral figures in the 1333 altarpiece with the Dormition of the Virgin in the Musei Civici, Vicenza (fig. 3)—a work described by Francesca Flores d’Arcais as a “sort of manifesto” of the artist’s early maturity, characterized by a “subtle equilibrium” between traditional Byzantine forms and modern Gothic elements.16 But rather than providing a terminus post quem for the Yale panels, as argued by past authors, the Vicenza altarpiece seems to represent a more advanced stage in the evolution of the artist’s idiom toward increasingly Gothic formulas. Absent from the Yale figures are the swaying linear rhythms that break up the severity of the poses; the gestures are more restricted, the mood more contained.

The most distinctive features of the Yale Baptist, such as the piercing eyes and dramatically lit facial structure, invite comparison with works associated with the controversial early phase of Paolo’s development in the decade leading up to the Vicenza polyptych, when his career seems closely intertwined with that of the so-called Master of the Washington Coronation.17 The beginning of this decade is marked by the dated 1321 Dossal of the Blessed Leone Bembo (fig. 4), now in the church of Saint Blaise, Vodnjan, Croatia, but originally located in the church of San Sebastiano, Venice.18 This much-debated work has been variously assigned to the young Paolo; to an anonymous “Master earlier than Paolo”; to the young Paolo in collaboration with the Master of the Washington Coronation; and, most recently, to the Master of the Washington Coronation himself.19 Bolstering an attribution to Paolo is the close relationship of the Vodnjan panel to the two shutters of the Triptych of Santa Chiara in the Civico Museo Sartorio, Trieste, generally given to the artist and unanimously placed within the third decade.20 The common authorship of the two works was already recognized by Giuseppe Fiocco and later emphasized by Pallucchini, who pointed to the identical figure types with “pin point eyes, highlighted nose, down-turned mouth, [and] verdaccio based flesh tones.”21 Although the Trieste shutters are sometimes dated around 1320,22 more or less contemporary to the Vodnjan panel, the treatment of the large figures painted on the outside of the wings more closely anticipates the Vicenza altarpiece, arguing for a somewhat later execution.23

The same morphological traits that characterize both the Vodnjan and Trieste panels, loosely indebted to the vocabulary of the Master of the Washington Coronation, are also peculiar to the Yale Saint John the Baptist. The correspondences between the Yale figures and those in the right wing of the Trieste triptych (fig. 5), despite the differences in scale, are especially compelling. A slightly earlier chronology for the Yale Saints is suggested perhaps by the greater rigidity of the poses and stiffer handling of the draperies, nearer to the Vodnjan painting. A dating for the Magdalen and John the Baptist between that work and the Trieste shutters, in the mid-1320s or slightly after, seems therefore plausible. Like those images, the Yale panels should ultimately be viewed as further illustration of the “stylistic continuity” between Paolo’s manner and that of the Master of the Washington Coronation, in the crucial period of his formation.24

No other fragments that might reasonably be associated with the Yale Magdalen and Baptist have yet been identified. A possible clue to the original appearance of the complex from which they were excised is offered, however, by the panels’ dimensions and horizontal wood grain. These suggest that they may have been part of a so-called pala ribaltabile, or folding altarpiece, similar to the examples produced by Paolo’s workshop around the middle of the century for the cathedral of Saint George in Piran (now Civico Museo Sartorio, Trieste) (fig. 6) and the cathedral of the Assumption in Rab, Croatia.25 Common to both of those altarpieces is the long, low, horizontal format, with an image of the Virgin and Child or the Crucifixion in the center, flanked by standing saints in separate compartments on either side, and, on the reverse, traces of upside-down figures sculpted in low relief, which would have been visible when the panel was turned or rotated upon itself.26 The design of the Piran altarpiece, which also includes standing figures of the Magdalen and Saint John the Baptist, may closely reflect that of the dismembered complex to which the Yale figures belonged. Painted on a single horizontal plank measuring 82.5 by 247 centimeters, it is divided into nine compartments separated by spiral colonettes supporting ogival arches—not unlike the framing elements that, judging from the incised profiles, must have enclosed the Yale figures. Additionally, the dimensions of the individual compartments with standing saints—60 by 22 centimeters—are almost identical to those of the present panels. Given the close structural correspondences, it is worth speculating whether the dismembered pala ribaltabile with the Yale Magdalen and John the Baptist, like so many other works produced in Paolo’s famous mainland workshop, could have provided the prototype for the altarpiece commissioned by Dalmatian patrons in Piran, several decades later.27 —PP

Published References

Venturi, Lionello. The Rabinowitz Collection. New York: Twin Editions, 1945., 11–12, pl. 6; Berenson, Bernard. Italian Pictures of the Renaissance, A List of the Principal Artists and Their Works, with an Index of Places: Venetian School. 2 vols. London: Phaidon, 1957., 1:128; Seymour, Charles, Jr. The Rabinowitz Collection of European Paintings. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1961., 7, 14–15, 55; Pallucchini, Rodolfo. La pittura veneziana del trecento. Venice: Istituto per la Collaborazione Culturale, 1964., 33, 97; Muraro, Michelangelo. Paolo da Venezia. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1970., 56, 101, 116; Seymour, Charles, Jr. Early Italian Paintings in the Yale University Art Gallery. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1970., 109–11, nos. 76a–b; Fredericksen, Burton B., and Federico Zeri. Census of Pre-Nineteenth-Century Italian Paintings in North American Public Collections. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1972., 601; Gloria Kury Keach, in Seymour, Charles, Jr., et al. Italian Primitives: The Case History of a Collection and Its Conservation. Exh. cat. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1972., 38, no. 27; Zeri, Federico, with Elizabeth E. Gardner. Italian Paintings: A Catalogue of the Collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art; Venetian School. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1973., 47; Kenney, Elise K., ed. Handbook of the Collections: Yale University Art Gallery. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1992., 134; Frinta, Mojmír S. Punched Decoration on Late Medieval Panel and Miniature Painting. Vol. 1, Catalogue Raisonné of All Punch Shapes. Prague: Maxdorf, 1998., 128; Marchi, Alessandro. “Trecento veneziano nelle terre adriatiche marchigiane.” In Pittura veneta nelle Marche, ed. Valter Curzi, 29–51. Milan: Cariverona, 2000., 35, 51n42; Pedrocco, Filippo. Paolo Veneziano. Milan: A. Maioli, 2003., 211; Rullo, Alessandra. “Paolo Veneziano.” In Dizionario biografico degli italiani. Rome: Istituto della Enciclopedia italiana, 2014. https://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/., 81:190–94

Notes

-

This provenance is first cited with a question mark by Charles Seymour, Jr., in the catalogue of the Rabinowitz Collection at Yale and was later repeated as hearsay: “Said to have come from the Museo Guidi in Faenza.” See Seymour, Charles, Jr. The Rabinowitz Collection of European Paintings. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1961., 14; and Seymour, Charles, Jr. Early Italian Paintings in the Yale University Art Gallery. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1970., 109–11, nos. 76a–b. The present author has not been able to find the origin of Seymour’s source in the Yale files or elsewhere. The panels are not mentioned in the 1902 sale of the Guidi collection (see Galleria Sangiorgi, Rome. Grande vente du Musée de la Noble Famille Guidi de Faenza. Sale cat. April 21–27, 1902.), although this alone does not preclude their having been in the possession of that dealer at some point before being acquired by the E. and A. Silberman Galleries. ↩︎

-

Evelyn Sandberg-Vavalà, “Maestro Paolo Veneziano: His Paintings in America and Elsewhere,” unpublished manuscript written for the Bulletin of the Worcester Art Museum, March 1939; quoted in Pallucchini, Rodolfo. La pittura veneziana del trecento. Venice: Istituto per la Collaborazione Culturale, 1964., 97. E. and A. Silberman Galleries in New York was established by Abris Silberman in 1928 as a branch of the family’s Viennese gallery. In 1938 Abris was joined by his brother Elkan Silberman. It may be presumed that Louis Rabinowitz, who purchased several other Italian paintings from Silberman, acquired the Yale panels sometime between 1939 and 1945. Though the Silberman provenance is not cited by Seymour, it is mentioned by Federico Zeri on the back of old photographs of the panels in the Fototeca Zeri, Federico Zeri Foundation, Bologna, inv. nos. 25979–80: “Paolo Veneziano, [before 1938, Wien & NYC, Silberman].” ↩︎

-

Inv. no. 1937.33, https://hvrd.art/o/230775. ↩︎

-

Seymour, Charles, Jr. The Rabinowitz Collection of European Paintings. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1961., 14. ↩︎

-

Inv. no. 190; Pallucchini, Rodolfo. La pittura veneziana del trecento. Venice: Istituto per la Collaborazione Culturale, 1964., 33. ↩︎

-

Muraro, Michelangelo. Paolo da Venezia. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1970., 56, 101, 116. ↩︎

-

Seymour, Charles, Jr. Early Italian Paintings in the Yale University Art Gallery. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1970., 109–111, nos. 76a–b ↩︎

-

Gloria Kury Keach, in Seymour, Charles, Jr., et al. Italian Primitives: The Case History of a Collection and Its Conservation. Exh. cat. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1972., 38. ↩︎

-

Inv. no. 1971.115.5, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/437249; Zeri, Federico, with Elizabeth E. Gardner. Italian Paintings: A Catalogue of the Collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art; Venetian School. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1973., 47. ↩︎

-

Marchi, Alessandro. “Trecento veneziano nelle terre adriatiche marchigiane.” In Pittura veneta nelle Marche, ed. Valter Curzi, 29–51. Milan: Cariverona, 2000., 35, 51n42. ↩︎

-

Pedrocco, Filippo. Paolo Veneziano. Milan: A. Maioli, 2003., 211. ↩︎

-

The Metropolitan Museum of Art Virgin is first recorded in the collection of Anton Reichel in Grossgmain, Austria, in 1912. According to Zeri and Gardner, the Yale panels’ “earlier provenance from Austria, whence they came to New York through the firm of Silberman and Co., may be an indication that they came from the same complex”; see Zeri, Federico, with Elizabeth E. Gardner. Italian Paintings: A Catalogue of the Collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art; Venetian School. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1973., 49. Although it is possible that the Yale panels were brought to New York from the Viennese branch of the Silberman Galleries, there is no documentary evidence that they were ever included in the Reichel collection or in any other Austrian private collection. ↩︎

-

Museo Diocesano, Cesena; Pedrocco, Filippo. Paolo Veneziano. Milan: A. Maioli, 2003., 176–77, no. 18. ↩︎

-

Inv. no. 1927.19. 6a, https://worcester.emuseum.com/objects/29796/saint-john-the-baptist. The triptych is currently divided between the Worcester Art Museum, Massachusetts (1927.19), the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. (inv. no. 1939.1.143, https://purl.org/nga/collection/artobject/284), and the Musée du Petit Palais, Avignon, France (inv. no. 20194). See Boskovits, Miklós. Italian Paintings of the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries. Washington, D.C.: National Gallery of Art, 2016. NGA Online Editions, https://purl.org/nga/collection/catalogue/italian-paintings-of-the-thirteenth-and-fourteenth-centuries., 325–33 (with previous bibliography). ↩︎

-

Based on the most recent photographs of the Tbilisi polytpych (reproduced in Kalandia, George. European Art and Georgia: European Painters in Georgia and Western European Art in Georgian Collections. Tbilisi, Georgia: Cezanne Printing House, 2018., 12–17), it is difficult to accept Filippo Pedrocco’s direct attribution to Paolo or his proposed chronology in the second half of the 1330s; see Pedrocco, Filippo. Paolo Veneziano. Milan: A. Maioli, 2003., 156–57. The ruinous state makes it difficult to evaluate that work properly, but the general physiognomy of the figures suggests a much later execution by the artist’s workshop. ↩︎

-

Flores d’Arcais, Francesca. “Paolo Veneziano.” In Enciclopedia dell’arte medievale. Rome: Istituto della Enciclopedia Italiana, 1998.. ↩︎

-

On the personality of the Master of the Washington Coronation, long identified with Paolo Veneziano, see, most recently, Guarnieri, Cristina. “Il passaggio tra due generazioni: Dal Maestro dell’Incoronazione a Paolo Veneziano.” In Il secolo di Giotto nel Veneto, ed. Giovanna Valenzano and Federica Toniolo, 153–201. Venice: Istituto Veneto di Scienze, Lettere ed Arti, 2007., 153–201; and Boskovits, Miklós. Italian Paintings of the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries. Washington, D.C.: National Gallery of Art, 2016. NGA Online Editions, https://purl.org/nga/collection/catalogue/italian-paintings-of-the-thirteenth-and-fourteenth-centuries., 301–13. Most art historians now generally agree that he belonged to a generation preceding Paolo, proposing to identify him with his older brother Marco or, more likely, his father, Martino da Venezia. For the various suggestions, see Guarnieri, Cristina. “Il passaggio tra due generazioni: Dal Maestro dell’Incoronazione a Paolo Veneziano.” In Il secolo di Giotto nel Veneto, ed. Giovanna Valenzano and Federica Toniolo, 153–201. Venice: Istituto Veneto di Scienze, Lettere ed Arti, 2007., 155–56n9. ↩︎

-

Though traditionally referred to as a dossal, it is generally thought that the panel was the front of a wood sarcophagus in which the relics of the Blessed Leone Bembo were kept and that it was used as an altar frontal. ↩︎

-

The attribution of the Vodnjan painting to Paolo, first proposed by Giuseppe Fiocco in his fundamental article on the young Paolo (see Fiocco, Giuseppe. “Le primizie di maestro Paolo Veneziano.” Dedalo 11, no. 4 (1930–31): 878–93., 881–84), was strongly upheld by Rodolfo Pallucchini; Pallucchini, in Bettini, Sergio, et al. Venezia e Bisanzio. Exh. cat. Venice: Electa, 1974., no. 86 (with previous bibliography). The panel is accepted as a work of Paolo by, among others, Flores d’Arcais, Francesca. “Paolo Veneziano.” In Enciclopedia dell’arte medievale. Rome: Istituto della Enciclopedia Italiana, 1998.; Fossaluzza, Giorgio. Da Paolo Veneziano a Canova: Capolavori dei musei veneti restaurati dalla regione del Veneto, 1984–2000. Venice: Marsilio, 2000., 42–43; Flores d’Arcais, Francesca. “Paolo Veneziano e la pittura del trecento in Adriatico.” In Il trecento adriatico: Paolo Veneziano e la pittura tra Oriente e Occidente, ed. Francesca Flores d’Arcais and Giovanni Gentili, 19–31. Exh. cat. Cinisello Balsamo, Milan: Silvana, 2002., 22; and Krekic, Anna. “La tavola del beato Leone Bembo di Paolo Veneziano e la sua copia tardo-quattrocentesca.” Arte in Friuli, arte a Trieste 24 (2005): 147–60., 147–60. The attribution was rejected by Viktor Lazareff, in Lazareff, Viktor N. “Maestro Paolo e la pittura veneziana del suo tempo.” Arte veneta 8 (1954): 77–89., 88n1, who assigned the painting to the “instructor of Maestro Paolo”; and, most recently, by Filippo Pedrocco, in Pedrocco, Filippo. Paolo Veneziano. Milan: A. Maioli, 2003., 47–50, 212, A 46. Cristina Guarnieri, in Guarnieri, Cristina. “Il passaggio tra due generazioni: Dal Maestro dell’Incoronazione a Paolo Veneziano.” In Il secolo di Giotto nel Veneto, ed. Giovanna Valenzano and Federica Toniolo, 153–201. Venice: Istituto Veneto di Scienze, Lettere ed Arti, 2007., 166–67, 169–70, thought that it reflected the participation of a young Paolo in a work conceived by the Master of the Washington Coronation. For Boskovits, it belongs exclusively to the hand of the Master of the Washington Coronation; see Boskovits, Miklós. Italian Paintings of the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries. Washington, D.C.: National Gallery of Art, 2016. NGA Online Editions, https://purl.org/nga/collection/catalogue/italian-paintings-of-the-thirteenth-and-fourteenth-centuries., 307, 310n22. ↩︎

-

The triptych’s shutters were added to the central panel, executed by the so-called Master of the Triptych of Santa Chiara, at a later date. They were first inserted into Paolo’s oeuvre by Evelyn Sandberg-Vavalà; see Sandberg-Vavalà, Evelyn. “Maestro Paolo Veneziano.” Burlington Magazine 57, no. 331 (1930): 160–82., 177. ↩︎

-

Fiocco, Giuseppe. “Le primizie di maestro Paolo Veneziano.” Dedalo 11, no. 4 (1930–31): 878–93., 882; and Pallucchini, Rodolfo. La pittura veneziana del trecento. Venice: Istituto per la Collaborazione Culturale, 1964., 26. The relationship between the two works “clearly produced in the same moment by the same artist” is also acknowledged by Pedrocco (in Pedrocco, Filippo. Paolo Veneziano. Milan: A. Maioli, 2003., 50), despite his attribution of both to a “Master earlier than Paolo.” For Guarnieri, in Guarnieri, Cristina. “Il passaggio tra due generazioni: Dal Maestro dell’Incoronazione a Paolo Veneziano.” In Il secolo di Giotto nel Veneto, ed. Giovanna Valenzano and Federica Toniolo, 153–201. Venice: Istituto Veneto di Scienze, Lettere ed Arti, 2007., 169, the correspondences between the Santa Chiara laterals and the Vodnjan panel are an indication that the latter may be the result of a collaboration between the young Paolo and the Master of the Washington Coronation. ↩︎

-

Travi, Carla. “Il maestro del trittico di Santa Chiara: Appunti per la pittura veneta di primo trecento.” Arte cristiana 80 (1992): 81–96., 81, 90–91nn5–6; and Boskovits, Miklós. “Paolo Veneziano: Riflessioni sul percorso (Parte I).” Arte cristiana 97 (2009): 81–90., 81–82, 86n9, 87–88n16. ↩︎

-

Based on circumstantial evidence, Maria Walcher Casotti, in Walcher Casotti, Maria. Il trittico di S. Chiara di Trieste e l’orientamento paleologo nell’arte di Paolo Veneziano. Istituto di Storia dell’Arte Antica e Moderna 13. Trieste: Università degli Studi, 1961., 6–16, proposed a date between 1328 and 1330. Her arguments were accepted by Pallucchini (in Pallucchini, Rodolfo. La pittura veneziana del trecento. Venice: Istituto per la Collaborazione Culturale, 1964., 26), followed by Bianco Fiorin, in Bianco Fiorin, Marisa, Decio Cio Setti, Laura Ruaro Loseri, and Maria Walcher Casotti. Pittura su tavola dalle collezioni dei Civici Musei di Storia ed Arte di Trieste. Exh. cat. Milan: Electa, 1975., sec. 2, no. 1. A dating toward the end the decade was reiterated, more recently, by Giorgio Fossaluzza (in Fossaluzza, Giorgio. Da Paolo Veneziano a Canova: Capolavori dei musei veneti restaurati dalla regione del Veneto, 1984–2000. Venice: Marsilio, 2000., 42). ↩︎

-

Miklós Boskovits, in Boskovits, Miklós. Italian Paintings of the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries. Washington, D.C.: National Gallery of Art, 2016. NGA Online Editions, https://purl.org/nga/collection/catalogue/italian-paintings-of-the-thirteenth-and-fourteenth-centuries., 307, noted that the Vodnjan picture “provides further evidence of the essential stylistic continuity between the manner of Paolo and that of the older master.” The exact nature of the artists’ relationship remains unclear. Cristina Guarnieri (in Guarnieri, Cristina. “Il passaggio tra due generazioni: Dal Maestro dell’Incoronazione a Paolo Veneziano.” In Il secolo di Giotto nel Veneto, ed. Giovanna Valenzano and Federica Toniolo, 153–201. Venice: Istituto Veneto di Scienze, Lettere ed Arti, 2007., 157) highlighted the particular structure of a family workshop in which the older, more archaic master—whether Paolo’s father, Martino, Paolo’s brother Marco, or an altogether different painter in the same workshop—possibly determined the stylistic direction and models to be imitated into the third decade of the fourteenth century and argued that Paolo initially intervened in projects conceived and designed by this artist. ↩︎

-

For a discussion of these altarpieces, see Guarnieri 2019, 39–53. The term pala ribaltabile was coined by Guarnieri to describe the moving mechanism of such works, whose function was related to the display of the relics of saints associated with the altar or church for which they were commissioned. Among the earliest examples of this type of altarpiece, which seems to have originated in Venice, is that in the cathedral of San Giusto, Trieste, attributed by Guarnieri to the Master of the Washington Coronation but more convincingly identified by Boskovits (in Boskovits, Miklós. Italian Paintings of the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries. Washington, D.C.: National Gallery of Art, 2016. NGA Online Editions, https://purl.org/nga/collection/catalogue/italian-paintings-of-the-thirteenth-and-fourteenth-centuries., 301, 302n3) as the work of an anonymous late thirteenth-century painter influenced by Palaeologan art. The most famous and sophisticated example of a pala ribaltabile is undoubtedly the Pala d’Oro painted by Paolo and his sons between 1343 and 1345 for the basilica of San Marco, Venice. Guarnieri’s examination of the structure of the Piran and Rab altarpieces confirms that their original design was a simplified version of the much more complex system of the Pala d’Oro, resolving many of the technical issues that have hitherto confounded scholars when analyzing these structures (see note 26, below). The possibility, discussed by Guarnieri, that other works by Paolo usually classified as dossals might also conform to the specifications of a pala ribaltabile suggests that his workshop may have specialized in their production. ↩︎

-

Guarnieri, Cristina. “Lo svelamento rituale delle reliquie e le pale ribaltabili di Paolo Veneziano sulla costa istriano-dalmata.” In La Serenissima via mare: Arte e cultura tra Venezia e il Quarnaro, ed. Valentina Baradel and Cristina Guarnieri, 39–53. Padua: Padova University Press, 2019., 45–48. The remains on the reverse of the Piran panel have misled more than one scholar to presume that the altarpiece was left unfinished; see Luisa Morozzi, in Flores d’Arcais, Francesca, and Giovanni Gentili, eds. Il trecento adriatico: Paolo Veneziano e la pittura tra Oriente e Occidente. Exh. cat. Cinisello Balsamo, Milan: Silvana, 2002. 158–60, no. 28 (with previous bibliography). As pointed out by Guarnieri, however, the fact that similar upside-down gesso imprints appear on the back of the Rab altarpiece suggests that they were both conceived as mixed pale ribaltabili, with one side painted and the other sculpted. The presence of a metal plate with a large hole on one side of the Piran panel—to which corresponded another plate, now missing, on the other side—possibly indicates that the panel moved by turning on itself along a wooden axle; see Pizzolongo, Angelo. “Ipotesi tecnica per un support di sostegno e di rifunzionalizzazione del dispositivo di rotazione della pala di Pirano di Paolo Veneziano.” In La Serenissima via mare: Arte e cultura tra Venezia e il Quarnaro, ed. Valentina Baradel and Cristina Guarnieri, 54–56. Padua: Padova University Press, 2019., 54–57. Confirmation that the Piran altarpiece was originally commissioned for the cathedral rather than the baptistery, as sometimes stated, comes from Guarnieri’s clarification that the central image on the reverse was not another Virgin and Child, as hitherto supposed, but a representation of Piran’s patron saint, George, and the dragon. ↩︎

-

On the transfer of works of art, rather than painters, from Paolo’s mainland workshop to locations along the Adriatic Coast, see Cozzi, Enrica. “Paolo Veneziano e bottega: Il politico di Santa Lucia e gli antependia per l’isola di Veglia.” Arte in Friuli, arte a Trieste 35 (2017): 235–93., 235–93. ↩︎