To view the back of the cross, use the arrows beside the image at left.

Art market, Paris, 1926; Maitland Fuller Griggs (1872–1943), New York

The cross is composed of two pieces of wood, lap-joined perpendicular to each other. Each piece is 2.4 centimeters thick, with the painted surface of each recessed approximately 3 millimeters on both faces. Both pieces exhibit a moderate convex warp, forcing open the seams at the lap join—vertical on the obverse, horizontal on the reverse—but not resulting in significant losses of paint or gilding. The gilding overall is well preserved, although it is worn to the gesso on many of the raised moldings, especially in the lower half of the cross, and it is locally patched with powdered gold around the kneeling figures at the bottom. Losses to blues and reds have been inpainted on both sides of the cross, while flesh tones are largely intact, except for the kneeling saint (Francis?) on the obverse, whose head is entirely a modern invention. The angel’s wings on the obverse have also been retouched. The rapid application of white highlights in the draperies on the reverse are almost perfectly preserved. The red on the outer sides of the cross is also well preserved, as are most of the mordant gilt lozenges painted atop it, but where the gilding has flaked away, the residues of glue binder have decayed to black.

This double-sided processional cross is painted on both faces with closely related but not identical images of the Crucified Christ. On both the obverse and reverse, full-length standing figures of the mourning Virgin and Saint John the Evangelist fill the left and right lateral terminals, respectively, and a half-length mourning angel is seen in the upper terminal. On the obverse, the angel faces left, toward the Virgin; on the reverse, the angel faces right, toward the Evangelist. The Virgin on both sides of the cross wears a dark blue cloak over a red dress; on the obverse, she crosses her arms over her chest, while on the reverse she clasps her hands before her. Saint John wears a red cloak over a light blue robe. On the obverse of the cross, he holds a book of his Gospels in his left hand and touches his right to his chest; on the reverse, his head rests on his right arm in a gesture of consuming grief. The angels, both front and back, wear violet cloaks over blue tunics, considerably lighter on the obverse than on the reverse. The bottom of the cross on both sides is filled with a kneeling figure in a Franciscan habit, looking up to adore the Crucified Christ: on the reverse, a woman in a Clarissan habit, who may be presumed by her halo to represent Saint Clare; on the obverse, a severely damaged friar, again with a halo, who may be presumed to be Saint Francis.

Each of the three upper terminals of the cross is shaped as a trilobe extension of the basic cross form. The bottom of the cross repeats the lateral lobes of these extensions but tapers to a straight, flat termination at the very bottom, where the cross was affixed by a peg to a processional pole. The outermost lobe at the top and sides and the two lobes at the bottom are decorated with geometric roundels of blue and red in imitation of enamel or verre églomisé. These five roundels are identical on both faces of the cross. The background of the cross is gilt and enlivened with an engraved spiraling rinceau motif. Each projecting lobe at the terminals, the two lobes at the bottom, and the four corners of the projecting rectangle marking the center of the cross are further embellished by the attachment of crystal beads nailed to the outside of the cross. It is not clear whether the beads presently attached to the cross (two are missing, one at each of the extreme lateral lobes) are original, but if not, they certainly imitate forms originally attached in these locations. The obverse and reverse faces of the cross are edged with a thin projecting molding, gilded evenly with the background. The outer edge is painted red and decorated with a running pattern of mordant gilt rhombuses around its entire periphery.

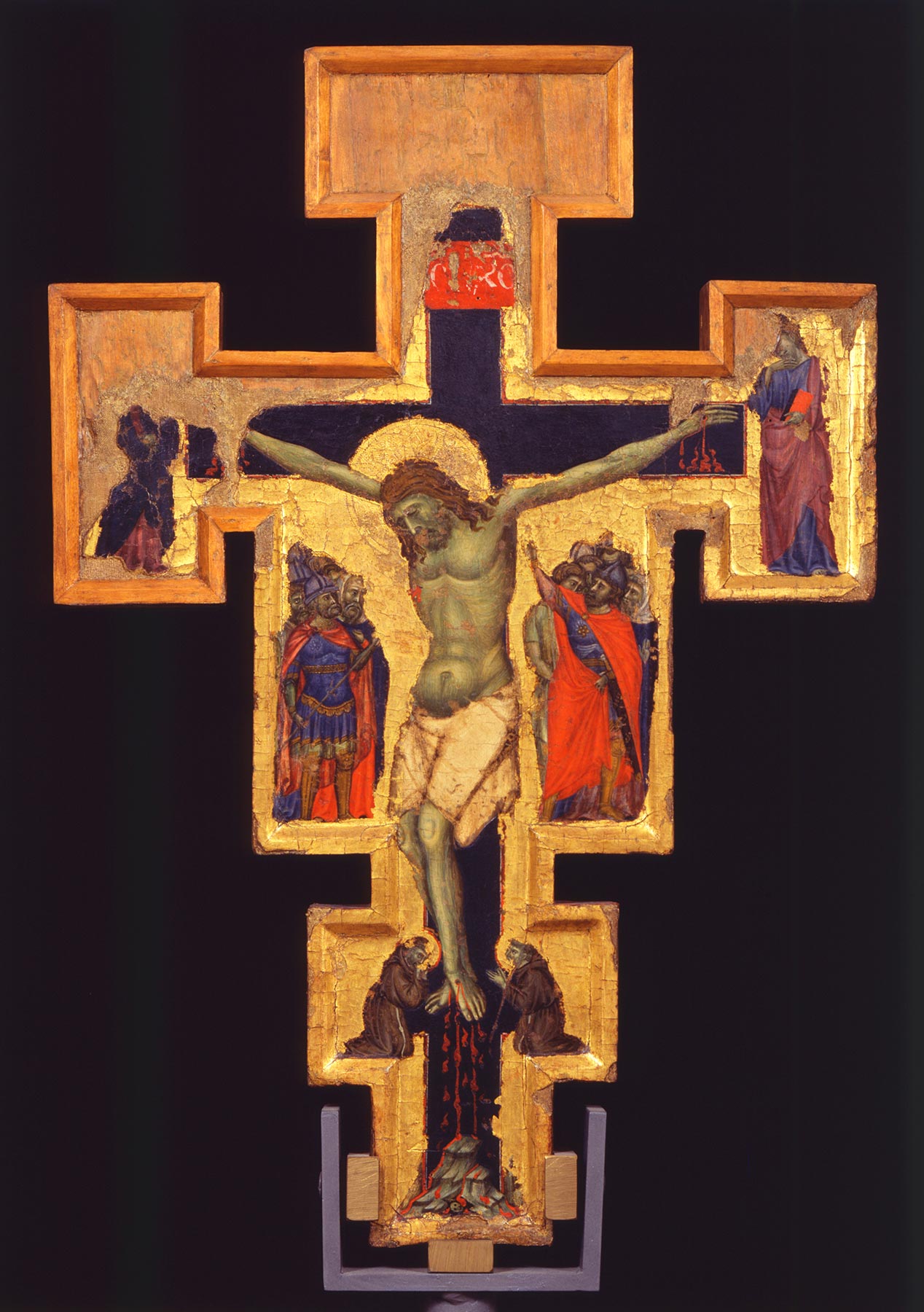

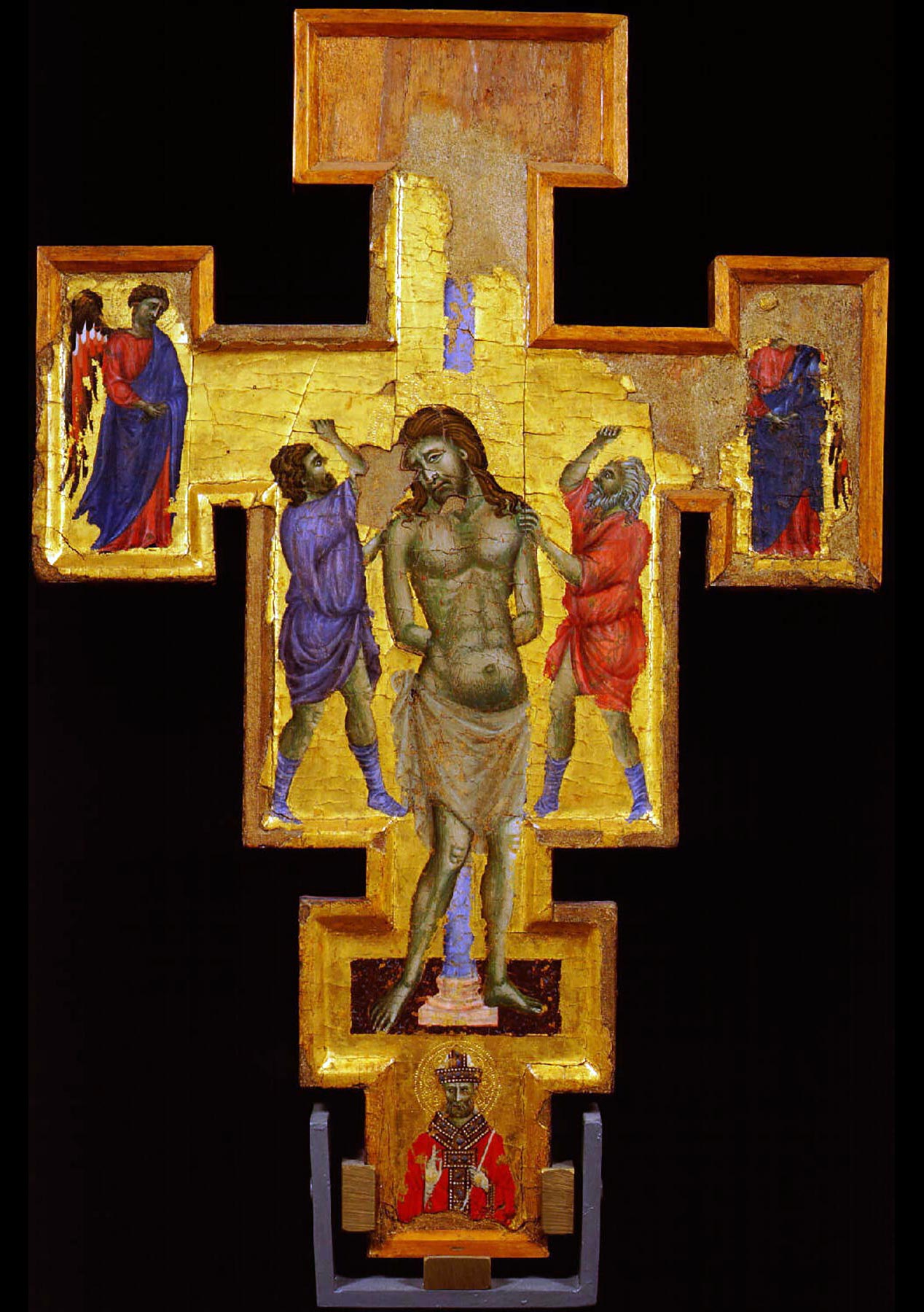

Attributed by Richard Offner to the Sienese school when it was purchased by Maitland Griggs in 1926,1 the cross was first recognized by Bernard Berenson as dependent instead on the polyglot stylistic culture of the so-called Cantiere d’Assisi:2 the Roman, Florentine, Umbrian, and Transalpine teams of artists engaged primarily during the last two decades of the thirteenth century on the fresco and stained-glass decoration of the Upper Church at the basilica of San Francesco in Assisi. Berenson specifically assigned it to an immediate follower of the Roman painter Pietro Cavallini, and nearly all subsequent discussion of the cross has focused on clarifying its relationship to the style of either Cavallini or his Tuscan contemporary at Assisi, Cimabue. In 1949 Edward Garrison recognized the similarities between this cross and a more elaborate processional cross of similar size in the Galleria Nazionale dell’Umbria, Perugia (figs. 1–2), labeling their author the “Processional Cross Master” and characterizing him as North Umbrian.3 The Perugia cross represents the Crucifixion on the obverse, with Roman soldiers in the apron, damaged full-length figures of the mourning Virgin and Saint John the Evangelist in the terminals, and two diminutive Franciscan saints kneeling in adoration at Christ’s feet (see fig. 1). The reverse portrays the Flagellation, with executioners filling the apron, two mourning angels in the terminals, and a half-length figure of a bishop saint at the foot of the cross (see fig. 2).

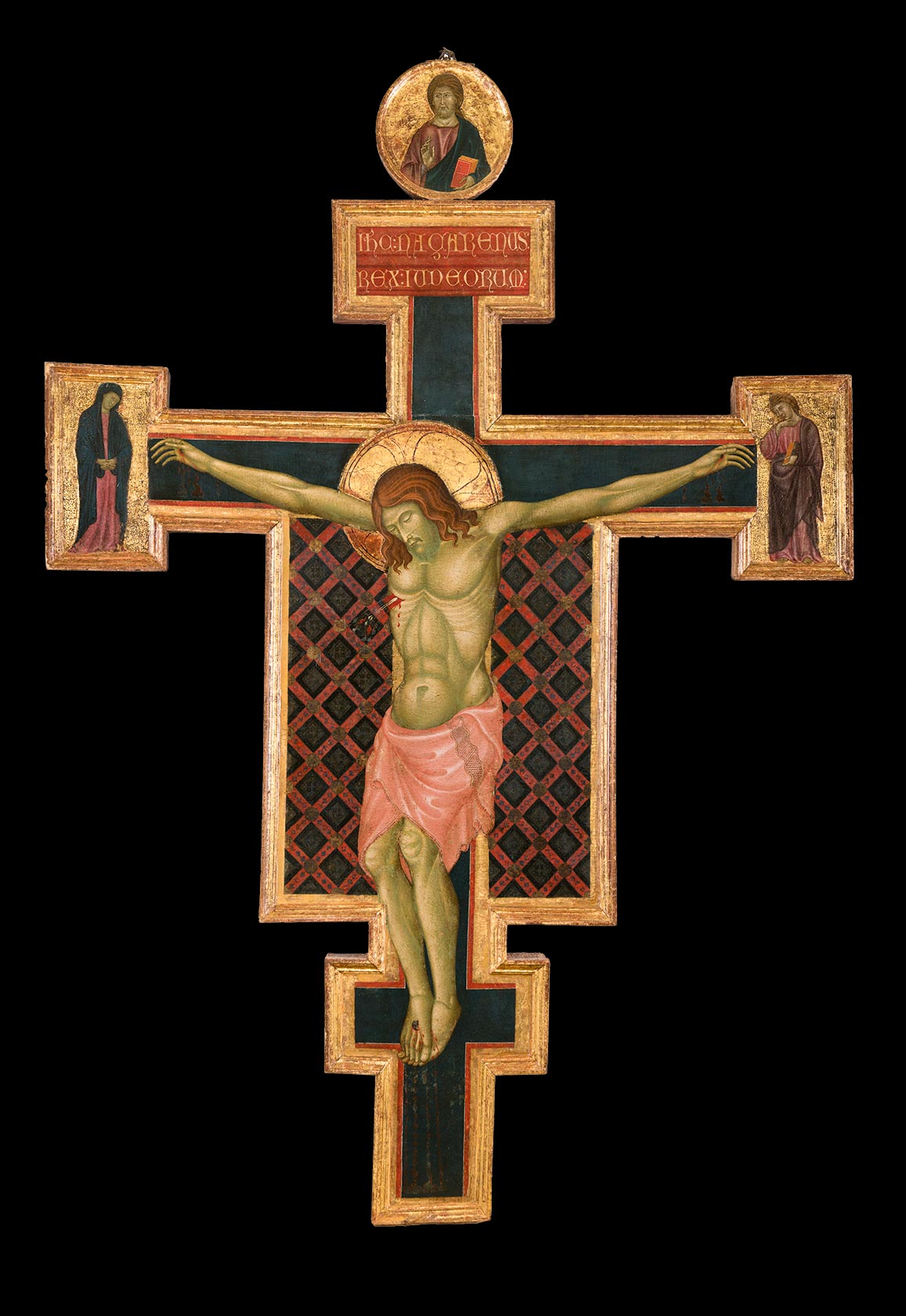

Carlo Volpe, in 1968–69, accepted Garrison’s argument relating the Yale and Perugia paintings, as have nearly all subsequent authors.4 Volpe also added a third work to the group: a monumental painted cross in the Museo Civico at Gubbio (fig. 3), on the basis of which the Yale cross has been known in all recent literature as by the Master of the Gubbio Cross. While this attribution has come to be universally accepted, scarcely two scholars have agreed on the exact outlines of such an artist’s personality or whether he might be identifiable as a stage in the career of another, better-known painter active in Perugia or Assisi in the years around 1300. All scholars, however, agree that the Yale and Gubbio crosses must be later works than the cross in Perugia. The Perugia cross (see figs. 1–2) reveals a closer reliance on the style and figure types of the frescoes in the Upper Church of the basilica of San Francesco, especially those attributed to the so-called Master of the Capture of Christ, an artist tentatively identified by Giordana Benazzi with the Master of the Gubbio Cross.5 It incorporates a Gothic figure of Christ whose lively and elegant silhouette derives from a type popularized in Umbria by Giunta Pisano and Cimabue. While Christ is shown with a single nail transfixing both feet, these are still splayed in opposite directions as they had been in earlier paintings, where each foot was shown pierced by a separate nail. The Yale and Gubbio crosses, instead, adopt a Giottesque model that became normative only after the turn of the century, in which Christ’s feet overlap in the same direction, forcing His knees forward in a spatially more realistic, less decorative manner. Accordingly, where the Perugia cross is generally dated ca. 1290 or slightly earlier,6 the Yale cross is dated as late as ca. 1310 or even 1320 in some studies.

Alessandro Conti was the first author to advance a substantive proposal for identifying the Master of the Gubbio Cross with another known artist and amalgamating their two oeuvres.7 Responding to an observation put forward earlier by Roberto Longhi, that miniaturists in Perugia forged a visual language widely imitated by monumental painters there,8 Conti proposed as an example that the artist identified by Longhi as the “Primo Miniatore Perugino”—author of a series of illuminations in the choir books from San Domenico in Perugia, now preserved in the Biblioteca Augusta there—was probably the same as the Gubbio Cross Master. Conti’s suggestion has been accepted in totum only by one subsequent writer, Marina Subbioni,9 but it has formed the basis for discussions by numerous authors who reject the identification. In a variant of the argument, Filippo Todini identifies three distinct hands at work on the San Domenico choir books, a Primo Miniatore Perugino, a Secondo Miniatore Perugino, and a third artist whom he identifies as Marino da Perugia (Marino di Elemosina di Forte, documented 1309–10).10 For Todini, the Secondo Miniatore Perugino, not the Primo Miniatore, is sufficiently similar in style to the Gubbio Cross Master that the two artists might be one. Elvio Lunghi rejects both these contentions.11 He identifies only two hands among the San Domenico choir books. One, the Primo Miniatore Perugino, is decidedly archaic and was probably of an older generation than the other. For Lunghi, the second artist is an amalgamation of Todini’s Secondo Miniatore and Marino da Perugia, presumably working on the project over a long arc of time, beginning with the reconsecration of the expanded church of San Domenico in 1304 and concluding at an unknown date prior to 1321. In that year, the feast of Corpus Domini was officially embraced by the Dominican order, but it is not included among the original texts in these choir books. Lunghi, furthermore, advances a hypothetical identification of the Primo Miniatore Perugino as Marino da Perugia’s father, Elemosina di Forte da Perugia (documented 1289–1312). This proposal was seconded by Marta Minazzato, who pointed out that both Marino and Elemosina are cited as painters and as miniaturists in documents.12

At the heart of these disagreements lie two separate issues: a divergence of opinion over interpretation of the twenty-six fully illuminated initials remaining in the thirteen volumes of the San Domenico choir books (plus three initials now in the Fondazione Giorgio Cini, Venice, removed from a missing fourteenth volume13) and differing views of the plausibility of linking the coloristic exuberance and narrative fantasy of manuscript illumination with the conventional formulae and restricted palette of larger panel paintings. Allowing for the possibility of overlap between the art forms, as is in any event implied by the few surviving documentary notices, it remains difficult to establish criteria for assessing similarity between them. The defining characteristic of Umbrian Gothic miniature painting, beginning with the Primo Miniatore Perugino (Elemosina di Forte?), is the remarkable freedom and originality of its spatial innovations, its narrative complexity and creativity, and above all its distinctive decorative vocabulary. All these qualities are conspicuously lacking in the three painted crosses associated with the Master of the Gubbio Cross: painted crosses by definition follow well-rehearsed formulae and rely for their efficacy on immediately recognizable compositional conventions.

It has not been noted anywhere in the extensive literature treating this question that the Yale cross is the work of two different artists: the obverse is not painted by the same hand as the reverse. Although they follow closely similar cartoons and were undoubtedly conceived in tandem, the obverse is painted in a much coarser technique, with shorter figural proportions and more expressive character traits. The feathers of the angel’s wings are painted using large unresolved daubs of color with thick impasto, whereas on the reverse they are more smoothly blended into each other. Christ’s hair on the obverse is a pattern of thick alternating strokes of dark red and brown, covering His head like a cap viewed nearly in full profile. On the reverse, it is a smoothly modeled field of auburn, parted at the center and falling naturalistically at the shoulders, permitting Christ’s head to be viewed more nearly in three-quarter profile. Christ’s rib cage and abdomen are also more smoothly modeled on the reverse, avoiding the stark contrasts of color that make the obverse seem more archaic. The greatest contrast between the two sides is visible in the draperies of the Virgin and Saint John the Evangelist: sharp, angular contrasts of light and shade on the obverse; on the reverse, fluidly painted lines of highlight rendered as saturate, high-key color against deeper local color. The artist responsible for the obverse of the Yale cross appears to be the same painter responsible for the double-sided processional cross in Perugia (see figs. 1–2), whereas the painter of the reverse of the Yale cross is demonstrably the same as the author of the larger painted cross in Gubbio (see fig. 3). Except through the Yale cross, the Gubbio and Perugia crosses do not establish a strong link between each other.14

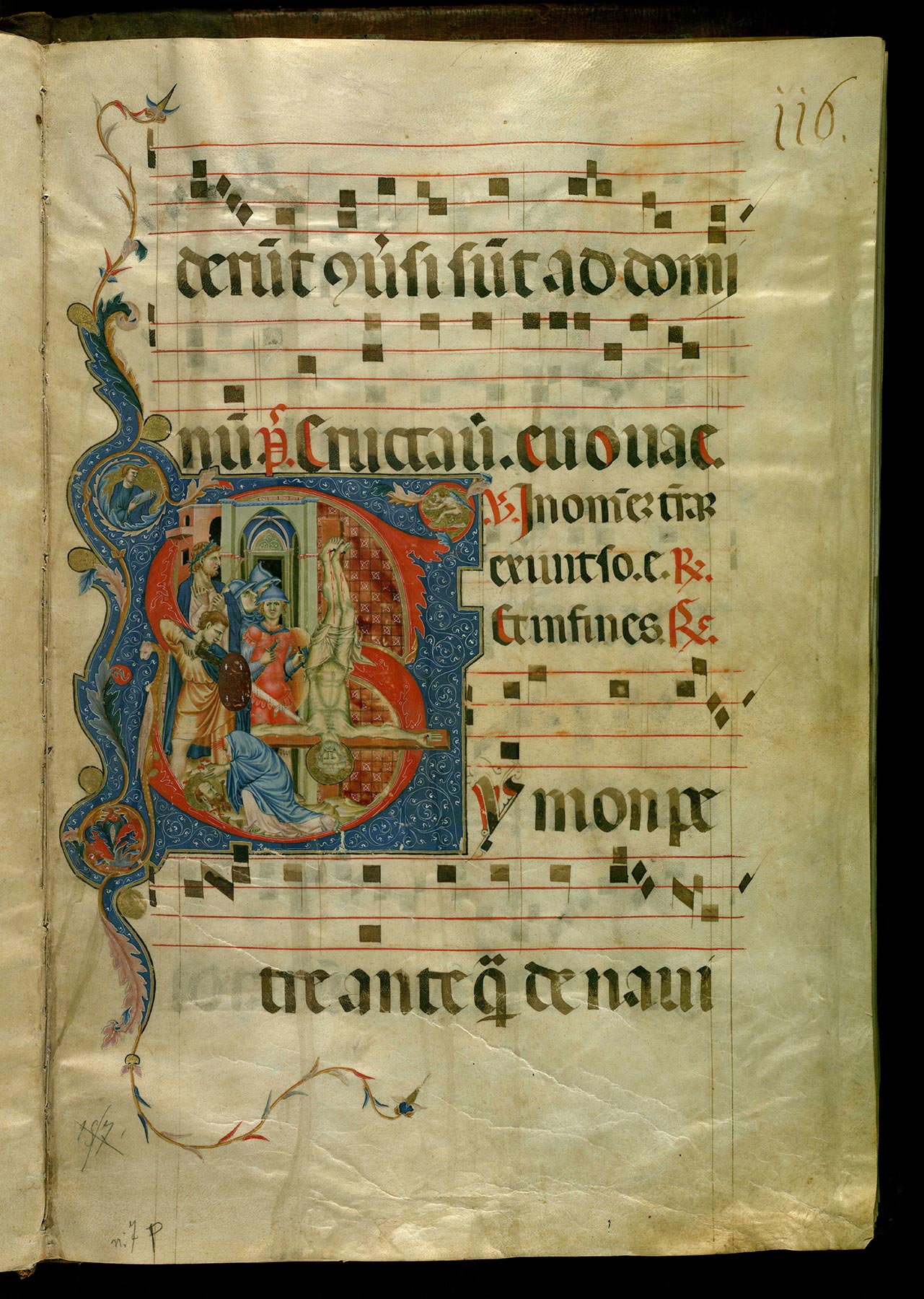

In light of this distinction of hands, the contentions that the Master of the Gubbio Cross might be the Primo Miniatore Perugino (Conti, Subbioni) or that he might instead be the Secondo Miniatore Perugino (Todini) both require closer scrutiny. Connections to the work of the Secondo Miniatore—in particular, the Lord’s Supper in an Initial A in Antiphonary H of the San Domenico choir books (fig. 4) or the Martyrdom of Saints Peter and Paul in an Initial S in Antiphonary F (fig. 5)—are entirely to be found among the forms and patterns on the reverse of the Yale cross. These are, in fact, sufficiently striking to imply that the two painters might indeed be the same. On the other hand, links to the work of the Primo Miniatore—such as the Ascension in an Initial P in the Fondazione Giorgio Cini (fig. 6)—are restricted to the obverse of the Yale cross and, once again, these are striking. The coincidence of the same two artists being engaged together on distinct collaborative projects might lend circumstantial support to Lunghi’s proposals that the Secondo Miniatore Perugino is actually an early stage in the career of Marino di Elemosina and that the Primo Miniatore and he were father and son. While it is reasonable to believe that the series of fourteen choir books at San Domenico required a considerable span of time to complete, it is equally reasonable to assume that the two faces of the Yale cross were painted all but simultaneously. If the identification of the two artists as Elemosina and Marino di Elemosina is correct, it would follow that the Yale cross should be dated close to 1304, certainly earlier than 1313, the hypothetical date of a signed panel by Marino in the Galleria Nazionale dell’Umbria, Perugia, representing the Virgin and Child Enthroned with Saint Paul, Saint Peter Celestine, and four angels.15 By that time, the style of Marino di Elemosina had matured beyond the stage at which it could be confused with the hypothetical Secondo Miniatore Perugino. A counterproposal to identify the Primo Miniatore Perugino, and therefore also the Master of the Gubbio Cross, as the Eugubine painter Palmerino di Guido16 was rejected, apparently correctly, by Linda Pisani in favor of a tentative association of this documented assistant of Giotto with the so-called Maestro Espressionista di Santa Chiara.17 —LK

Published References

Berenson, Bernard. Italian Pictures of the Renaissance: A List of the Principal Artists and Their Works with an Index of Places. Oxford: Clarendon, 1932., 141; “The Griggs Collection.” Bulletin of the Associates in Fine Arts at Yale University 13, no. 1 (November 1944): 2–3., 3; Garrison, Edward B. Italian Romanesque Panel Painting: An Illustrated Index. Florence: Leo S. Olschki, 1949., 25, 178, no. 448; Bologna, Ferdinando. Early Italian Painting: Romanesque and Early Medieval Art. Princeton, N.J.: Van Nostrand, 1964., 96; Berenson, Bernard. Italian Pictures of the Renaissance, A List of the Principal Artists and Their Works with an Index of Places: Central Italian and North Italian Schools. 3 vols. London: Phaidon, 1968., 1:83; Santi, Francesco. Galleria Nazionale dell’Umbria: Dipinti, sculture e oggetti d’arte di età romanica e gotica. Rome: Istituto Poligrafico dello Stato, 1969., 36; Seymour, Charles, Jr. Early Italian Paintings in the Yale University Art Gallery. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1970., 99–101, nos. 70a–b; Fredericksen, Burton B., and Federico Zeri. Census of Pre-Nineteenth-Century Italian Paintings in North American Public Collections. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1972., 600; Boskovits, Miklós. Pittura umbra e marchigiana fra medioevo e Rinascimento: Studi nella Galleria Nazionale di Perugia. Florence: Edam, 1973., 11–12, 34nn45–46, 71, fig. 27; The Cleveland Museum of Art: European Paintings before 1500; Catalogue of Paintings: Part One. Cleveland: Cleveland Museum of Art, 1974., 139; Donnini, Giampiero. “Una ‘crocifissione’ umbra del primo trecento.” Paragone 26, no. 305 (1975): 3–12., 8–9, fig. 9; Manuali, Giovanni. “Aspetti della pittura eugubina del trecento: Sulle tracce di Palmerino di Guido e di Angelo di Pietro.” Esercizi: Arte, musica, spettacolo 5 (1982): 5–19., 8–11; Corrado Fratini, in Castelnuovo, Enrico, ed. La pittura in Italia: Il duecento e il trecento. 2 vols. Milan: Electa, 1986., 2:605; Todini, Filippo. La pittura umbra dal duecento al primo cinquecento. Milan: Longanesi, 1989., 123; Kenney, Elise K., ed. Handbook of the Collections: Yale University Art Gallery. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1992., 132; Daniela Parenti, in Bon Valvassina, Caterina, and Vittoria Garibaldi, eds. Dipinti, sculture e ceramiche della Galleria Nazionale dell’Umbria: Studi e restauri. Florence: Arnaud, 1994., 89; Santanicchia, Mirko. “Pittura eugubina e ‘dintorni.’” In Il Maestro di Campodonico: Rapporti artistici fra Umbria e Marche nel trecento, ed. Fabio Marcelli, 70–85. Fabriano: Cassa di risparmio di Fabriano e Cupramontana, 1998., 73; Garland, Patricia Sherwin, and Elisabeth Mention. “Loss and Restoration: Yale’s Early Italian Paintings Reconsidered.” Yale University Art Gallery Bulletin (1999): 32–43., 32–35, fig. 1; Laurence Kanter and Pia Palladino, in Kanter, Laurence, and Giovanni Morello, eds. The Treasury of Saint Francis of Assisi. Exh. cat. Milan: Electa, 1999., 82–83, 85–86, no. 8; Dean, Clay. A Selection of Early Italian Paintings from the Yale University Art Gallery. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 2001., 13, 20–21, no. 3; Drabik, Caroline R. “Pre-Renaissance Italian Frames with Glass Decorations in American Collections.” M.A. thesis, Fashion Institute of Technology, New York, 2001., 119–21, no. 21; Subbioni, Marina. “Pittura e miniature nei corali di San Domenico di Perugia.” In Canto e colore: I corali di San Domenico di Perugia nella Biblioteca Comunale Augusta (XIII–XIV sec.). Perugia: Volumnia, 2006., 102, 104; Toscano, Bruno. “Maestro di Sant’Alò.” In Dal visibile all’indicibile: Crocifissi ed esperienza mistica in Angela da Foligno, ed. Massimiliano Bassetti and Bruno Toscano, 209–24. Exh. cat. Spoleto: Fondazione Centro Italiano di Studi sull’Alto Medioevo, 2012., 210; Marzia Sagini, in Pierini, Marco, ed. Francesco e la croce dipinta. Exh. cat. Cinisello Balsamo, Milan: Silvana, 2016., 140; Benazzi, Giordana. “Gubbio e il cantiere di Assisi: Il Maestro della Croce di Gubbio e il Maestro Espressionista di Santa Chiara.” In Gubbio al tempo di Giotto: Tesori d’arte nella terra di Oderisi, ed. Giordana Benazzi, Elvio Lunghi, and Enrica Neri Lusanna, 47–69. Exh. cat. Perugia: Fabrizio Fabbri, 2018., 51–52, 56, 182, 184, 186, fig. 2; Mirko Santanicchia, in Benazzi, Giordana, Elvio Lunghi, and Enrica Neri Lusanna, eds. Gubbio al tempo di Giotto: Tesori d’arte nella terra di Oderisi. Exh. cat. Perugia: Fabrizio Fabbri, 2018., 188

Notes

-

Verbal opinion, recorded in Seymour, Charles, Jr. Early Italian Paintings in the Yale University Art Gallery. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1970., 101. ↩︎

-

Berenson, Bernard. Italian Pictures of the Renaissance: A List of the Principal Artists and Their Works with an Index of Places. Oxford: Clarendon, 1932., 141. ↩︎

-

Garrison, Edward B. Italian Romanesque Panel Painting: An Illustrated Index. Florence: Leo S. Olschki, 1949., 25. ↩︎

-

Lectures at the Università di Bologna in the academic year 1968–69, cited in Boskovits, Miklós. Pittura umbra e marchigiana fra medioevo e Rinascimento: Studi nella Galleria Nazionale di Perugia. Florence: Edam, 1973., 11–12. ↩︎

-

Benazzi, Giordana. “Gubbio e il cantiere di Assisi: Il Maestro della Croce di Gubbio e il Maestro Espressionista di Santa Chiara.” In Gubbio al tempo di Giotto: Tesori d’arte nella terra di Oderisi, ed. Giordana Benazzi, Elvio Lunghi, and Enrica Neri Lusanna, 47–69. Exh. cat. Perugia: Fabrizio Fabbri, 2018., 52. ↩︎

-

Daniela Parenti, in Bon Valvassina, Caterina, and Vittoria Garibaldi, eds. Dipinti, sculture e ceramiche della Galleria Nazionale dell’Umbria: Studi e restauri. Florence: Arnaud, 1994., 89; and Marzia Sagini, in Pierini, Marco, ed. Francesco e la croce dipinta. Exh. cat. Cinisello Balsamo, Milan: Silvana, 2016., 140. ↩︎

-

Conti, Alessandro. La miniatura bolognese: Scuole e botteghe, 1270–1340. Bologna: Alfa, 1981., 71n37. ↩︎

-

Longhi, Roberto. “Apertura sui trecentisti umbri.” Paragone 17, no. 191 (1966): 3–17., 3–17. ↩︎

-

Subbioni, Marina. “Pittura e miniature nei corali di San Domenico di Perugia.” In Canto e colore: I corali di San Domenico di Perugia nella Biblioteca Comunale Augusta (XIII–XIV sec.). Perugia: Volumnia, 2006., 102. ↩︎

-

Todini, Filippo. “Gli antifonari di San Domenico e la miniatura a Perugia nel primo trecento.” In Francesco d’Assisi: Documenti e archivi, codici e biblioteche, miniature, 218–36. Milan: Electa, 1982., 218–22. ↩︎

-

Lunghi, Elvio. “Per la fortuna della basilica di San Francesco ad Assisi: I corali domenicani della Biblioteca ‘Augusta’ di Perugia.” Bollettino della Deputazione Storia Patria per l’Umbria 88 (1991): 43–68., 43–68; Lunghi, Elvio. “Marino da Perugia.” In Dizionario biografico dei miniatori italiani: Secoli IX–XVI, ed. Milvia Bollati, 730–32. Milan: Sylvestre Bonnard, 2004., 730–32; and Lunghi, Elvio. “Miniatore Perugino, Primo.” In Dizionario biografico dei miniatori italiani: Secoli IX–XVI, ed. Milvia Bollati, 783–86. Milan: Sylvestre Bonnard, 2004., 783–86. ↩︎

-

Marta Minazzato, in Medica, Massimo, and Federica Toniolo, eds. Le miniature della Fondazione Giorgio Cini: Pagine, ritagli, manoscritti. Cinisello Balsamo, Milan: Silvana, 2016., 220. ↩︎

-

Inv. nos. 22072–73, 22075. See Minazzato, in Medica, Massimo, and Federica Toniolo, eds. Le miniature della Fondazione Giorgio Cini: Pagine, ritagli, manoscritti. Cinisello Balsamo, Milan: Silvana, 2016., 215–20. ↩︎

-

Mirko Santanicchia correctly doubted that the Perugia and Gubbio crosses were by a single artist, but the majority of writers on this topic have not agreed with his observation; see Santanicchia, Mirko. “Pittura eugubina e ‘dintorni.’” In Il Maestro di Campodonico: Rapporti artistici fra Umbria e Marche nel trecento, ed. Fabio Marcelli, 70–85. Fabriano: Cassa di risparmio di Fabriano e Cupramontana, 1998., 73–74. ↩︎

-

Inv. no. 14; see Lunghi, Elvio. “Marino di Elemosina.” In Dipinti, sculture e ceramiche della Galleria Nazionale dell’Umbria: Studi e restauri, ed. Caterina Bon Valsassina and Vittoria Garibaldi, 108–11. Florence: Arnaud, 1994., 108–11. ↩︎

-

Subbioni, Marina. “Pittura e miniature nei corali di San Domenico di Perugia.” In Canto e colore: I corali di San Domenico di Perugia nella Biblioteca Comunale Augusta (XIII–XIV sec.). Perugia: Volumnia, 2006., 104. ↩︎

-

Linda Pisani, in Pierini, Marco, ed. Francesco e la croce dipinta. Exh. cat. Cinisello Balsamo, Milan: Silvana, 2016., 176–85. ↩︎